The Railway Arrives on the East Reserve

Ernest N. Braun

Although the name William Hespeler is most often associated with the founding of the town of Niverville, Manitoba, historically it is Joseph Whitehead who by virtue of his contract for the Pembina Branch Railway was the prime mover. He was the first European to make improvements on this part of Treaty One land.

Political Background

The construction of the railway between the Manitoba communities of Emerson and St. Boniface occurred during a prolonged period of complicated and tumultuous political changes at the federal level. In 1870, Louis Riel’s stand had forced the Government of Canada to create a new province, Manitoba, but Ottawa retained control over Crown Land in anticipation of realizing Conservative Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s dream of a transcontinental railway. That railway would link the new postage-stamp province and the great Northwest to Central Canada. Failing that, there was little chance of any large-scale settler movement from either English-speaking Ontario or French-speaking Quebec, although great efforts were made to that end. The railway was also justified as a way to link Manitoba to Central Canada and make it less vulnerable to annexation by the United States. The threat of Fenian raids in 1871 lent credence to that possibility, and occasioned the Second Red River Expedition and the establishment of a militia garrison in Manitoba to “pre-empt foreign aggression, stabilize the frontier, and provide law and order.”1 Moreover, in 1871 a condition of British Columbia’s entry into Confederation was the promise of a rail link to Central Canada.

In 1872, however, Macdonald’s plan for a transcontinental railway ran into serious complications when competing syndicates vied for the contract, one that was potentially extremely lucrative not only for the construction itself, but also for the power that control of the railway would bestow. One syndicate, headed by Sir Hugh Allan (of the Allan Shipping Line), involved American investors and a route to BC running west in part along existing railways in the US, and then back up to Manitoba, instead of going straight west over the Canadian Shield. The other one was headed by David L. Macpherson, and included investors from England who demanded an all-Canadian route. No amount of negotiation succeeded in amalgamating the two rival syndicates. Finally, in late July 1872, with a national election campaign already underway, Prime Minister Macdonald proposed an “agreement” that would give Allan the presidency of the new Canadian Pacific Railway on the condition that Macpherson would play along as joint contractor. This agreement was kept secret until after the election, and perhaps as a result Macdonald managed his very slim majority in October 1872. Then, as the new session of Parliament opened in March 1873, the Throne Speech declared that the “charter” for construction of the Pacific Railway had been granted to a “body of Canadian capitalists.” Later in the session, the government was challenged by a Liberal Member of Parliament who charged the Conservatives with accepting American money for their election campaign, effecting widespread bribery, and making a secret deal with Allan for his support.2 The affair later known as the Pacific Scandal, a reference to the grandiose idea of rail line to the Pacific, ultimately caused the fall of the Conservative government in November 1873. Immediately after Macdonald’s resignation on November 5, Liberal Alexander Mackenzie, as leader of the opposition, was appointed prime minister, and was elected to that office in the January 1874 federal election.

The new Liberal government had a radically different view of the railway, preferring to go a small step at a time, even if it meant the route would not be an all-Canadian one. One such step was the contract to build a line from Emerson, on the US border, to St. Boniface, a line known as the Pembina Branch of the Canadian Pacific Railway.3 At Emerson the line would link up with the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad segment to be built from Moorhead to the border. This route south through the US around Lake Superior is eerily similar to the ill-fated Allan plan that caused such opposition just a year before.

Joseph Whitehead

Enter Joseph Whitehead. In August 1874 the Liberal government contracted with Joseph Whitehead, former Liberal MP for Huron North, Ontario, to build the new line on the Canadian side.4 Whitehead had been a railway man in England, and also a railway contractor in Ontario before entering politics. As the lowest bid contractor for the Pembina Branch, it was now his responsibility to do the grading for the entire section between St. Boniface and Emerson.

Although no record exists of the reason the Whitehead chose the northwest quarter of Section 30-7-4E for a railway station, or the date, the choice of the site that would become Niverville was strategic. The entire route of the railbed ran east of the Red River, where he could avoid the expense of building a bridge over it, and still end in St. Boniface. This specific location also provided Whitehead with a second staging area just 22 miles from the first one in St. Boniface and exactly one-third of the way to the US border. Secondly, at Niverville the rail line would intersect with the Crow Wing Trail, the traditional land route for freight by Red River cart. Placing a rail station at that point would capture any remaining freight from the outback, should there be any, but more importantly served to make a statement; namely, that the Trail now served no purpose. Thirdly, positioning the station at the edge of the best prairie land along that route made sense, as William Hespeler immediately understood when he was apprised of it. Grain for export had already been gathered from this area and shipped south by river steamers, and Hespeler anticipated a steep increase in this, witness his prompt contract with Surveyor William Pearce for a town plan, and the commissioning of a grain elevator even before the rail line was completed.

What Whitehead did not know before his choice of the location or before his investment there was that the station would lie at the edge of the Mennonite Rat River or East Reserve, an area whose settlers dreamed of becoming a grain-producing breadbasket as they had in Ukraine. Apparently unaware of difficulties developing about the new line at the political and financial level, Whitehead had a sod-turning ceremony in late September of 1874, and began grading the railbed. He invested heavily in the Niverville site. In the October 10 edition of the Manitoba Free Press, he issued an advertisement for 150 teams of horses and 500 labourers, who should report to the site “about 20 miles south” of Winnipeg immediately, each preferably with his own blanket. This is without doubt the Niverville site.

Right from the beginning, the grading was not to be without its own problems. There was dissatisfaction on a number of fronts: the quality of the food on the part of the workers, the importing of labour from the US, the lack of preference for local settlers wiped out by the grasshoppers, and of course the slow pace of the project, as well as a lingering resentment about the location of the railway route east of the Red River instead of west. One newspaper commentator also noted that really those immigrant settlers who had brought enough supplies to get established should not be given these jobs (an oblique reference to an earlier comment saying that Mennonites were standing ready to take the jobs), and reported with some satisfaction that none of them took advantage of the opportunity anyway. When winter closed in, only a small part of the grading had been done, even though Whitehead had publicly speculated he could have it done in six weeks.5 Reports vary that between six miles and “a considerable portion” had been graded by freeze-up, when Whitehead returned to Ontario.

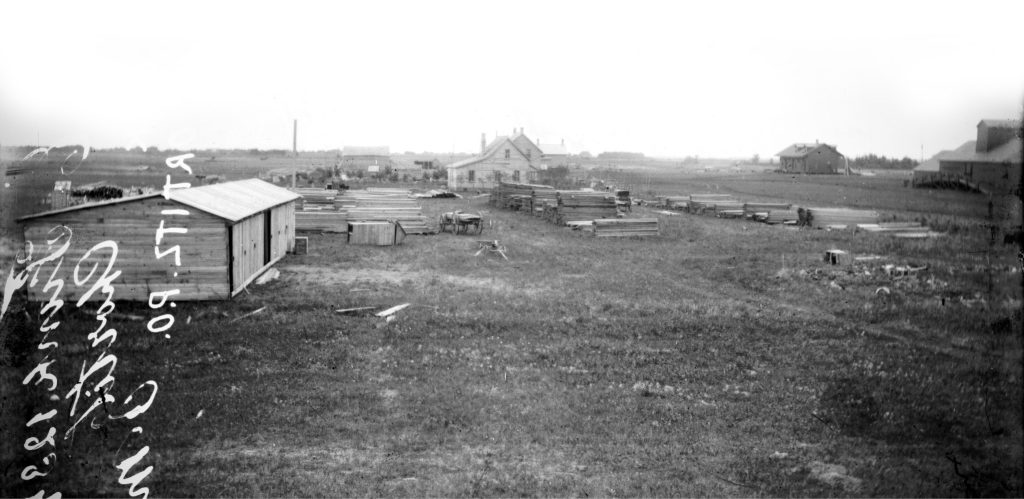

Realizing that his prediction for the completion of the grading in six weeks had been unrealistic, and that the project would probably extend into the whole of the next year, Whitehead wrote the Department of Interior on December 15, 1874, from his home in Clinton, Ontario, requesting permission to purchase the west half of Section 30-7-4E. He had built “shanties, storehouses and stables” and dug a 65-foot well. He planned to break some land there and seed it to oats in the spring of 1875 to feed the hundreds of horses needed for the grading of the rail line. The well likewise would serve the men and the horses. He already had a hired man living there ready to cut rails needed to fence in the land.6

John S. Dennis, Sr., as Surveyor General, responded immediately on behalf of the Department of the Interior to Whitehead’s request. He advised Whitehead that the land in question “is contained within the limits of the block set apart for Mennonite immigrants,” and that he would have to contact Jacob Y. Shantz about whether this purchase was possible.7 In late December 1874, a letter from the Dominion Lands Office to Shantz explained the request and asked Shantz to reply about the possible “dissatisfaction” that the Mennonites might express in this regard.8 Perhaps surprisingly, Shantz evinced no reluctance about the request, and in fact welcomed it, saying in part that “it would be well to have a Town started there to get a Post Office too there.”9 With this positive response it is curious to see that although the Dominion Lands Office immediately opened a file for Whitehead’s homestead application, nothing came of it, and it lies incomplete to this day.

In late May 1875, Whitehead returned to Manitoba, and work on the grading recommenced, continuing until early November when Whitehead paid off most of his workforce. It was clear by then that there would be delays in construction of the railway itself, for although the grading was complete, the contract for laying the steel had not even been tendered by the end of 1875, and indeed the project stalled shortly thereafter as it became clear that the American side was still 90 miles from the border.

Work on Whitehead’s project came up against the realities of the worldwide economic recession that had begun with a financial crisis in the US in October 1873, and that soon affected the Canadian economy. By early 1875 the entire Pacific Railway project had ground to a standstill, including the tiny 63-mile Pembina Branch. All of Whitehead’s plans and investment (totaling $1700–1800 for Niverville alone) were now in abeyance. South of the border the newly formed St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway stalled completely in the aftermath of the crash, and there was no point to building the Canadian part to the border without having the American rail line there.

The hiatus lasted more than two years. Then in spring of 1877 the project was reactivated with Whitehead again in charge, this time with a contract to lay the steel and run the line. He had purchased a slightly used locomotive and shipped it to Fisher’s Landing in Minnesota. In the meantime, the Governor General and Lady Dufferin had nailed down the first spike of the track in St. Boniface on September 29, 1877, at the precise location where the Dawson Road crosses the CPR line, a carefully selected symbolic place.10 Track-laying began the same day under the supervision of G.C. Swinbank, a long-time subcontractor for Whitehead and great-grandson of George Stephenson, the inventor of the first locomotive in Britain. On their return journey to the US, the vice-regal couple encountered the locomotive at Fisher’s Landing, Minnesota, on October 2, 1877. Whitehead promptly named it the Countess of Dufferin, and changed its number from CPR No. 2 to CPR No. 1. The locomotive and several railway cars arrived in St. Boniface on Tuesday morning, October 9, 1877, to great fanfare, Whitehead himself pulling the steam whistle as the riverboat S.S. Selkirk pushed the barge on which it sat to No. 6 warehouse where the public could examine the “iron horse.” Then the Selkirk steamed to below the Point Douglas ferry where the track had been laid to the river’s edge on the east side of the Red. Church bells pealed across the city. Ironically, the S.S. Selkirk had just brought the instrument of its own demise, for the train would soon make the riverboat obsolete. Moreover, the arrival of a locomotive west of the Great Lakes would now facilitate the building of the rest of the Canadian Pacific Railway across Canada to British Columbia. The celebration was justified, for indeed the arrival of the railway was a game-changer for the Mennonite Rat River Reserve, for Winnipeg, for Manitoba, and for Confederation.

The task of laying the track was broken into several sectors, the first from St. Boniface south, the second from Niverville (one third of the way) south, and the third from Pembina north, designed to meet at Dominion City. The contract (Contract No. 5, one of several railway contracts held by Whitehead) stipulated that the work needed to be done by a deadline usually given as December 1, 1878. Perhaps in view of the urgency of the deadline, the crew worked on Sunday, November 24, a transgression duly reported by an Emerson clergyman, and netting each of the workmen a fine. In St. Boniface Whitehead erected a sawmill near the station to cut his own sleepers, but there is no evidence that Whitehead invested anything beyond the minimum at most of the other nodes along the line, like Otterburne, or Dufrost. The other sites where significant capital and effort were expended were Dominion City, where a trestle bridge needed to be built to cross the Roseau River, and Arnaud, where the track crossed Mosquito Creek. Niverville was unique in that there was no river to cross. The intersection with the Crow Wing Trail appears to be the main advantage of the site, in addition to its placement one-third of the way to the border.

On December 3, 1878, the last spike was driven in at Dominion City by the 18-year-old daughter of the section foreman, to the chagrin of the men who had with varying success taken a crack at it. The Countess brought Canadian officials to the site, and an American train carrying American dignitaries met them there. In that moment Manitoba entered the industrial age, connected at last by rail to Central Canada, even if not by an all-Canadian route. Isolation, the main factor that made Manitoba unattractive to settlers, was now moot. Goods could be shipped both ways at competitive rates, immigration would become attractive, the cost of living in Manitoba would normalize, and the rail connection to the US would make completing the transnational railway possible in western Canada.

The Railway Changes the East Reserve

The implications for the province of Manitoba were significant, and for Mennonites no less so. Perhaps the most immediate advantage, as Shantz had predicted in 1874, was the establishment of a new post office in Niverville in May of 1879. Prior to this point all mail addressed to the Mennonite East Reserve accumulated in Fort Garry until somebody brought it back to the Reserve with them and distributed it to friends and relatives. The first postmaster on the East Reserve was Otto Schultz. He and his business partner Erdman Penner had moved here seeking to capitalize on the promise the railway offered. Other significant village centres on the Reserve, like Chortitz, Hochstadt, and Steinbach, only received a post office in 1884, five years later. This early postal address explains the otherwise puzzling references in many “Pioneer Portraits of the Past” articles to families having “first settled near Niverville” on the East Reserve before migrating to the West Reserve, whereas genealogical information clearly shows that in fact very few came from there. This likely reflects the fact that Niverville was the post office for much of the Reserve until 1884.

Then, as early as November 1879 a new station was built in Niverville, with telegraph service. This meant that passengers and freight could now be conveyed directly between St. Boniface and the Reserve. This also meant that the depot at the Shantz sheds just south of Niverville was no longer needed to store freight carted from the Rat River and Red River junction, as had been done since 1874. The storehouse built there by Shantz in 1875 had served in the interim. Purchasing agent Abraham Doerksen (1827–1916) would trudge almost thirty miles to Fort Garry on foot from his homestead in Schönthal, make purchases on behalf of the Mennonite settlers, and arrange for a river steamer to deposit them at the confluence of the Rat and the Red rivers. Here they could be picked up directly by the Mennonites or carted to the Shantz storehouse five miles away.

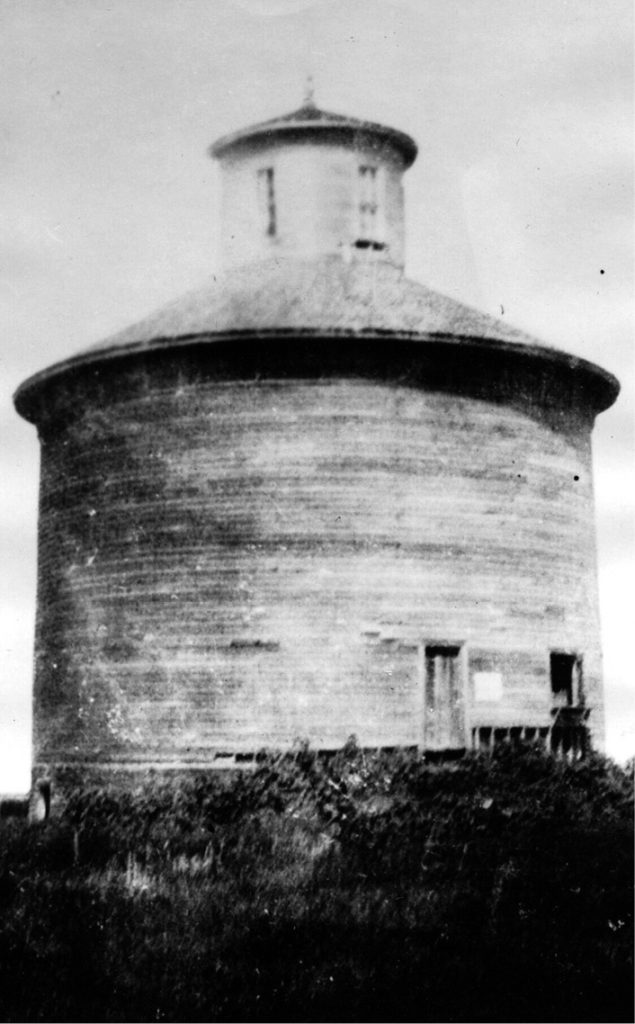

Because of its location on the line, Niverville was also a good place for a water tank, which was constructed in November 1880. To service this tank, the CPR commissioned a new well in 1881, nine feet in diameter and lined with bricks. This tank at the Niverville station made it an important stop since that water source was critical for the steam locomotives, and few of the other stations boasted that amenity. The tank was used until the 1950s, when steam locomotives were retired in favour of diesel. When the station was closed due to the decline of passenger traffic in the mid-1960s, the well was covered with railroad ties and dirt. The station itself, built after fire destroyed the first one in 1922, was dismantled by the Wittick brothers of Niverville, and residences were built with the lumber. The well site was lost until 2012 when a tractor driven by a town employee broke through the rotted sleepers and fell into the well. Only the large three-point hitch mower saved the driver from serious injury. The town decided to fill in the well with rubble, despite the fine brickwork revealed by the accident, brickwork that confirmed the opinion of the Manitoba Free Press of it as “one of the best on the line.”11 Local historians hope to have the well restored to create a pocket park celebrating the role the railway played in the founding of Niverville.

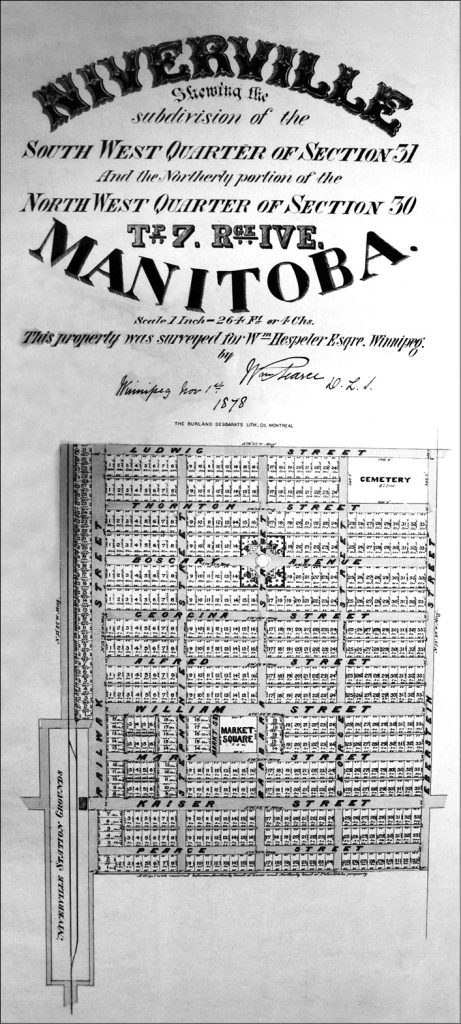

Although it was Whitehead who selected the site, its potential value was apparently better understood by William Hespeler, who as immigration agent for Manitoba and the North-West Territories was likely apprised of the site choice by Shantz. Hespeler wasted no time in purchasing the land around the station from its owners, Abraham Friesen and Peter Bernhard Dyck, converting eighty acres into a town plan by 1878. He commissioned William Pearce to survey the site and draw up a detailed town plan. Dated November 1, 1878, it included a market square and back lanes. The street names were those of the Hespeler and Pearce families. Clearly Hespeler anticipated a demand for town lots in the new railway town, which would have all the amenities needed for a large population.

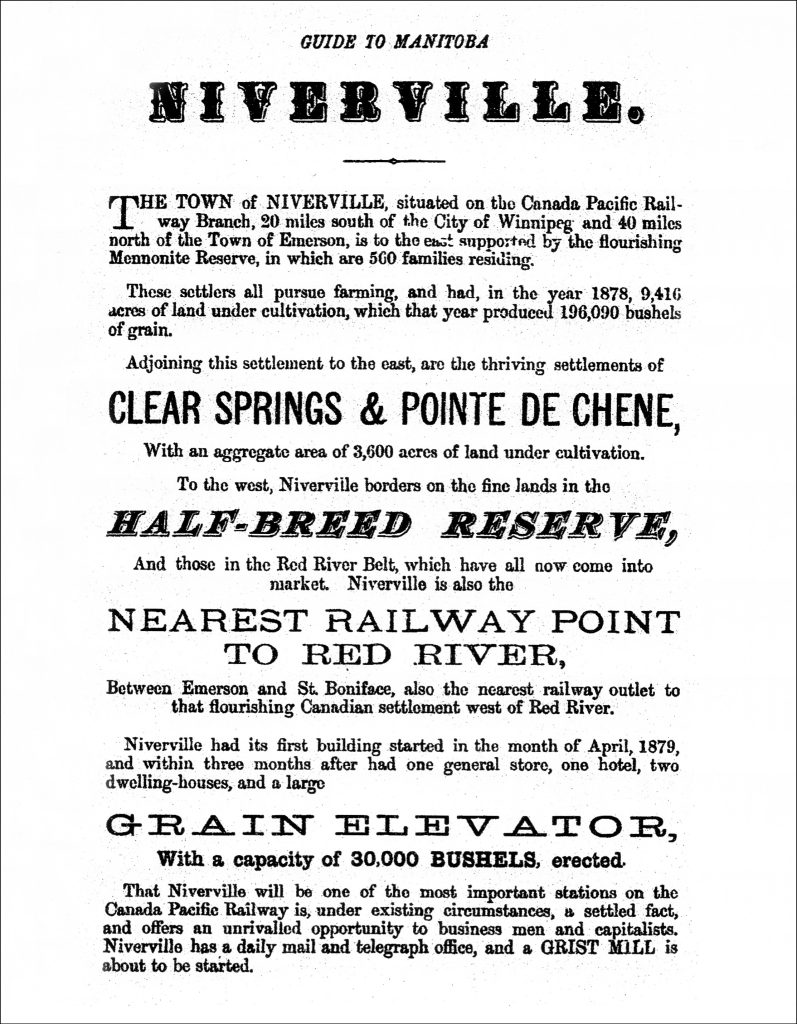

Then, not content to have others build those amenities, Hespeler commissioned the construction of a grain elevator in 1879, with a capacity of 25,000 bushels (later upgraded to 30,000), expecting that the grain-producing potential of the area would merit the investment. He also built a hotel and a livery barn. Erdman Penner, noted Mennonite entrepreneur, relocated his store from Tannenau (an abandoned village nine miles due east of Niverville, where he had expected the railway to run) and set up shop just east of the tracks. Within a year of the completion of the rail line, Niverville was set to be a major service centre for the entire Mennonite East Reserve.

An even more significant implication of the railway for the East Reserve was its potential for the grain and flour industries. Up to 1876 Manitoba was a net importer of flour, but with the harvest of 1876 wheat was in fact exported, local demand having been met for the first time since the coming of the Selkirk settlers. The elevator was the signal that grain could now be brought to the larger market in an economically feasible way, as opposed to the previous situation in which the river steamer held a monopoly on the shipping, at rates that rendered Manitoba wheat less than competitive. Wheat became the single greatest product of the prairies within five years of the arrival of the railway, and rural flour mills quickly grew to service local demand, while gigantic mills that used new roller technology to produce flour for export were constructed in Winnipeg. What neither Hespeler nor Whitehead anticipated was the delay in Niverville’s becoming a depot for bulk wheat delivery. The reason was the impenetrable swamp to the east of Niverville, which made hauling wheat to the station difficult until the land was drained by the Manning Canal in 1908, almost twenty years later. By that time some advantage had been lost, since a railway now ran through Giroux just northeast of Steinbach, and roads to Winnipeg had improved. As a result, the town that Hespeler envisioned did not materialize until the population boom of the bedroom commuter demographic in the 1970s, and more particularly at the turn of the twenty-first century, when Niverville continued to be the fastest growing community in Manitoba, but not because of the railway.

While wheat was not a major factor in the development of the southern townships or villages like Grunthal, Gruenfeld, Bergfeld, or even Steinbach, the railway did nonetheless promote growth and productivity in the East Reserve. The markets that were needed were for farm products ranging from potatoes to eggs and poultry which could now be sold to agents in Carey, Otterburne, or Niverville, and thereby save the farmer a trip to Winnipeg. What had taken several days of travel, bribes at the bridge or market square, and long hours of stand-up sales could now be done in half a day.

The completion of the Pembina Branch of the railway had two further ramifications that went well beyond Niverville or even Winnipeg. First, trade with the US increased significantly, with a daily transportation mechanism much cheaper than the steamboat monopoly, which had been strangling the province. Secondly, this reliable and affordable access to the rest of the industrialized world made work on the rest of the track to British Columbia possible. Without it the track west from Georgian Bay would have been delayed significantly to the point that BC legislature might have issued a secession bill again, this time successfully.

Conclusion

Joseph Whitehead entered the history books of the CPR through his role in constructing the railway, and he will be forever associated with the Countess of Dufferin, the iconic symbol of the rise of Manitoba from an isolated Red River Colony to the Keystone Province which would soon boast a city known as the Chicago of the North. Whitehead later laid more track both north to Selkirk, and east to Kenora, a contract that involved some bidding shenanigans. He continued to operate the Pembina Branch until the new Canadian Pacific Railway incorporated in 1881 and subsequently took over the operations from him. Moreover, it was his locomotives that were used to construct the track westward to British Columbia where the Countess eventually was retired.

However, he has never received his due as the ultimate founder of Niverville. Hespeler got the credit for founding the community, and even had the town named after him for a short while, but “Niverville,” the name given by the railway, soon eclipsed his name. Although the promotional flyer for the town, produced and circulated in 1880, touted it as “one of the most important stations of the Canada Pacific Railway” and as “an unrivalled opportunity to business men and capitalists,” in fact neither of these assertions materialized, in part at least due to poor access through the swamps east of Niverville, and likely in part because of the high tariffs set by the government to protect Central Canada’s interests. Niverville did become a service centre within two or three years, and a very important one for East Reserve Mennonites. However, it remained a relatively small village for almost a century. When the boom came, it did so not because of the railway, but because of the automobile, which enabled commuter traffic and spawned the concept of a bedroom community.

- Peter Burroughs’ three objectives of the Expeditionary Force as cited by David Grebstad in “Outpost: The Dominion of Canada’s Colonial Garrison in Manitoba, 1870 to 1877,” Canadian Military History 28, no. 1 (2019): 15. ↩︎

- Pierre Berton, The National Dream: The Last Spike (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1974), 74. ↩︎

- ↩︎

- Harold A. Innis, A History of the Canada Pacific Railway (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1923), 89. ↩︎

- Manitoba Free Press, September 19, 1874, 5. ↩︎

- Library and Archives Canada (LAC), RG 15, D-II-1, letter to Minister of the Interior dated December 15, 1874, Clinton, Ontario. Later referenced as vol. 2367. ↩︎

- LAC, RG 15, D-II-1, vol. 2077, letter to Whitehead, December 15, 1874. ↩︎

- LAC, RG 15, D-II-1, vol. 2185, letter to Shantz, December 29, 1874. ↩︎

- LAC, RG 15, D-II-1, vol. 2480, letter to J.S. Dennis, the Surveyor General, December 31, 1874, Berlin, Ontario. ↩︎

- See address of James Rowan to Governor General and the Countess of Dufferin on September 29, 1877. ↩︎

- Manitoba Free Press, August 31, 1881. ↩︎