Reorienting the West Reserve: Mennonites and the Railway

Hans Werner

The settlement in the 1870s of the Mennonite West Reserve in south central Manitoba is an early and representative example of the colonization, occupation, and reorientation of what had been Indigenous prairie space, a landscape they had inhabited “since the world began.”1 The section-township-range survey imposed a rectangular grid on the trails, crossings, and hunting areas used by Indigenous peoples to make a home on the lake bottom landscape of Manitoba’s Red River Valley. After the signing of Treaty One, and the completion of the survey, eighteen of the sections were designated by the government for settlement exclusively by Mennonites. Although the Mennonites who came from the Russian Empire to the West Reserve in the 1870s wanted to remain separate from others, they needed supplies and would soon require transportation to markets for their grain surpluses. The railway revolutionized the transport of people and goods and was instrumental in the colonization project. Railways would transform the economic geography and the settled landscape of the West Reserve a number of times between 1875, when the first Mennonites arrived, up to their gradual decline after the peak of the railway era in the 1920s.

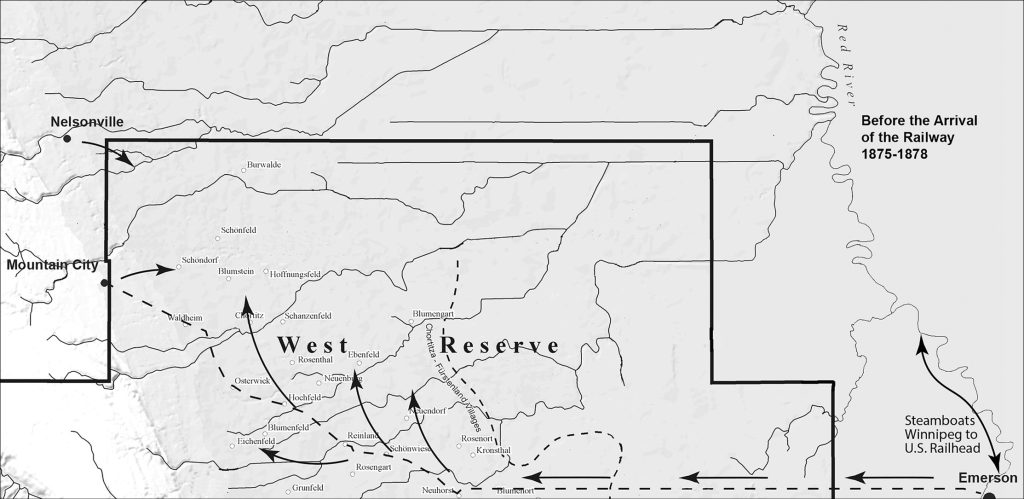

Before the Railway, 1875–1878

Mennonites from the Chortitza and Fürstenland colonies in the Russian Empire were the first settlers destined for the land between the Red River and the Pembina Escarpment. They travelled by train from Quebec City to Sarnia, then by boat on the Great Lakes to Duluth, by train to the railhead in Minnesota, and finally by riverboats to Fort Dufferin, just north of where Emerson was being established. While they waited at Fort Dufferin for the survey of their lands to be completed, they organized as one church and elected religious and civic leaders. Then they moved on to the prairie to establish their villages on what they believed to be the most desirable land in the Reserve. Mindful of the challenge of breaking the tall grass prairie and looking for good drainage, they chose the sandier lands on the secondary beaches of the former Lake Agassiz below the Pembina Escarpment in the most western part of the Reserve. By 1878 some twenty-five villages had been established with the village of Reinland serving as the religious and civic ‘capital.’ For the first years Mennonite farm families were preoccupied with putting up the initial shelter and breaking enough land to grow their own food and feed for their oxen and horses. Supplies had to come by riverboat from the railhead in the United States which had advanced to Fisher’s Landing near Grand Forks by 1875.2 Emerson, on the Red River at the international border, quickly became the depot for the steamboats that plied the Red River between Winnipeg and the railhead in the United States. Established in the fall of 1873 in anticipation of a rail link to the United States, Emerson soon became a possible competitor for Winnipeg as the future hub of the west. After 1876, as a local historian suggests, Emerson became “the trading centre for an area that stretched 200 miles westward along the international border.”3

The main route used by Mennonites to purchase the supplies they needed roughly followed the earlier North West Mounted Police expedition and Boundary Commission trails that had been used to survey the boundary and to establish a Canadian presence on the new frontier. After going slightly north after leaving Emerson, the route went parallel to the international border before passing just north of Blumenort, the first Mennonite village. At Neuhorst the route angled to the northwest, passing successively through, or by, Schönwiese, Reinland, Hochfeld, Osterwick, and Waldheim before arriving at Mountain City, a growing town just outside of the West Reserve. Mountain City and Nelsonville were ‘English’ towns located just outside of the west corner of the reserve. These towns became service centres for nearby Mennonite villages for a time. For the first few years the unmarked Post Road, as it would eventually be called, was in the words of one traveller, “a primitive road … across the virgin prairie.”4 Before the arrival of the railway from Winnipeg to Emerson, it was also the main route used to purchase supplies for the pioneering villages.

The Pembina Branch, 1878–1882

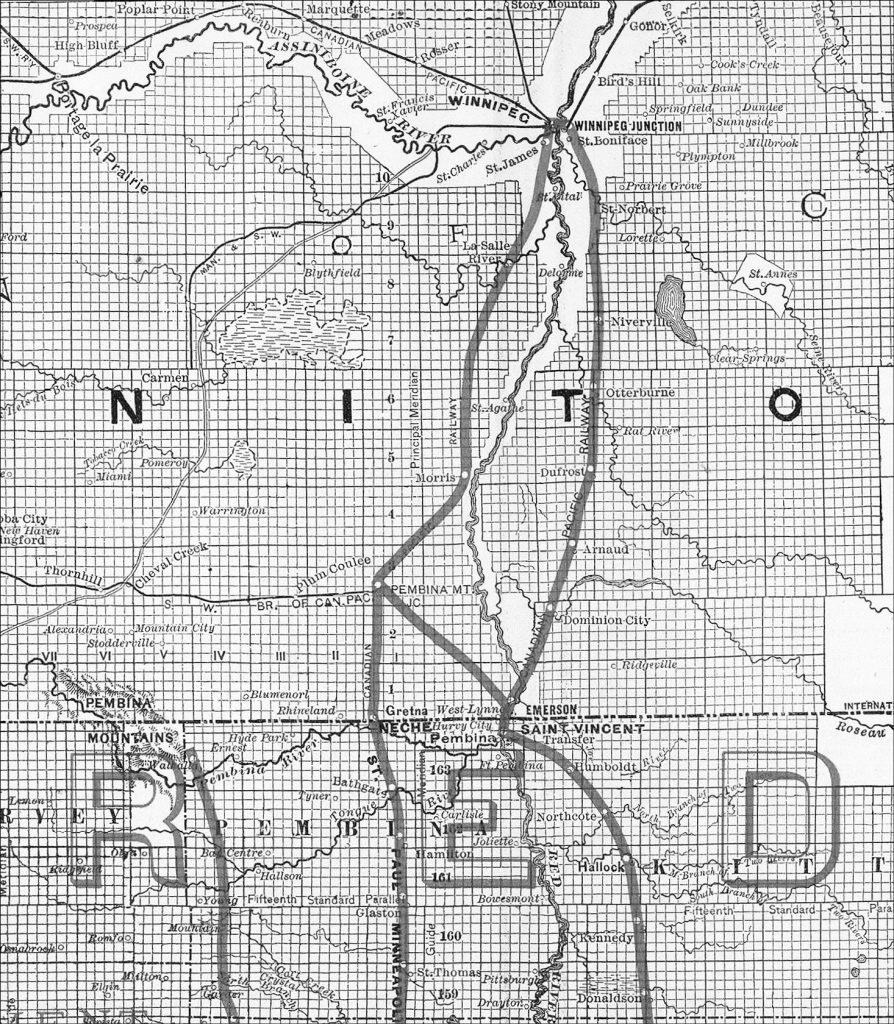

Railways and the ‘hardening’ of the international border would factor heavily into the development of the West Reserve after 1878. In the early days of the new Confederation, Canada’s survival was not a given and annexation to the United States remained a real threat. The Conservative government under John A. Macdonald had been ambitious in creating a nation from ‘sea to sea,’ but its viability was ultimately dependent on a connection that would solidify a country whose boundaries defied geography. The scandal that erupted over Macdonald’s handling of the contract to build an all-Canadian transcontinental railway sent his government to defeat in the 1874 election and Alexander Mackenzie and the Liberals came to power. The Liberals favoured a route through the United States to bypass the difficult terrain of the Canadian Shield. They also favoured Free Trade with the United States. The tenure of the Mackenzie Liberals pointed to a ‘softer’ border with the United States and in keeping with that sentiment the first railway to be built on the Canadian prairies went from St. Boniface to the international border at Emerson. The line from St. Boniface to Emerson was to be built by the federal government as the first leg of the Canadian section of a line that would connect the Western provinces to Eastern Canada through the United States. The arrival by riverboat of the steam locomotive, the Countess of Dufferin in Winnipeg in 1877 signalled the start of construction and by November 1879 the first train arrived in Emerson. The Pembina Branch was initially operated by the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway, but would later be incorporated into the Canadian Pacific Railway (C.P.R.).

The arrival of the railway immediately changed the nature of transportation along the Red River. As J. E. Têtu, the Dufferin Immigration Agent noted in his annual report “river navigation, as a means of transport for immigrants coming to this country is a thing of the past.” He effusively extolled the virtues of train travel. The trip to Manitoba was now “being more rapidly made, and it being less tedious, immigrants are in better condition, and moreover, in much better spirits than formerly.”5 The railway improved the fortunes of Emerson and soon the Hudson Bay Company established West Lynne on land it owned across the river opposite Emerson to capture some of the West Reserve market. At the time of the completion of the Pembina Branch in 1879, Mennonites from the Bergthal Colony who had initially settled on the East Reserve began moving to the unsettled areas of the West Reserve. New villages sprang up on the lower areas of the West Reserve although the very poorly drained sections in the north east would remain largely unsettled until they could be drained in later decades.

By the 1880s Mennonites on the reserve were also growing grain in excess of their immediate needs and the volume of grain being transported to Emerson and West Lynne steadily grew. By 1883, West Reserve farmers produced 211,743 bushels of wheat, an amount that had grown from 35,048 just four years earlier. By 1878, increased traffic and the problem of visibility in winter prompted Isaac Mueller, the Vorsteher (civil leader) of the West Reserve to order villagers to prepare wooden posts to mark the route that was being used to transport supplies to the reserve and, increasingly, grain to Emerson. The popular route would become known as the ‘Post Road.’ The Schellenbergs in Neuanlage, the Giesbrechts in Reinland, and William Brown’s hotel near Neuhorst were spots to spend the night as a stagecoach made its run along the Post Road from Emerson to Mountain City.6 Mountain City and Nelsonville had their own ambitions and by 1881 Nelsonville was the county seat and boasted a population of one thousand. John Warkentin’s study of the reserves points out that by early 1880s, West Reserve agriculture “had arrived at a stage where a railway was essential for further development.”7 The growing market to the west of Emerson and West Lynne prompted an economic boom for the two rival towns and the air was filled with rumours of railway lines extending to the West to capture the business of Mennonites and the increasing numbers of non-Mennonites settling further west.8

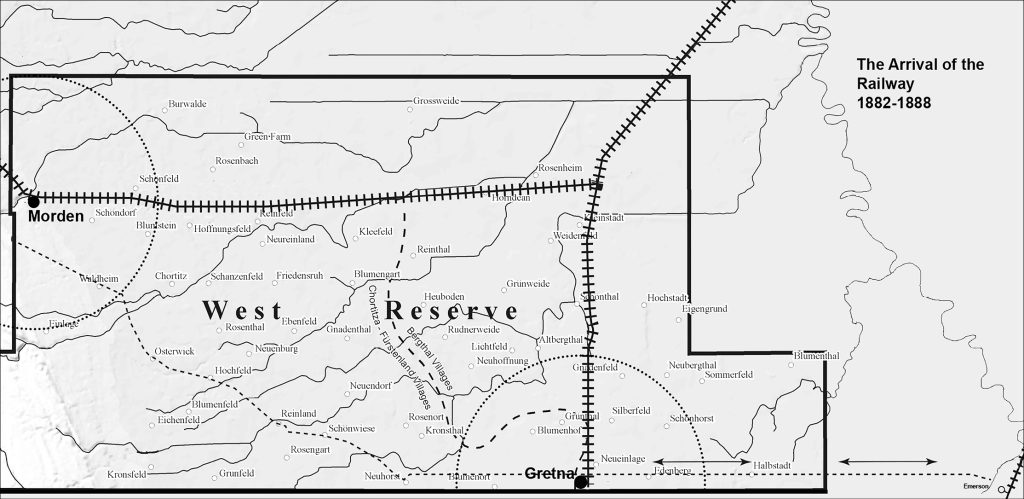

The Railway Arrives, 1882–1888

John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives returned to power in the 1878 election and the National Policy of the Conservatives was set to be implemented. This policy included a Canadian route for the transcontinental railway and high tariffs, both of which did not bode well for the town of Emerson, a ‘city’ of one thousand people.9 Construction of the transcontinental railway began immediately and by 1883 there was an all-Canadian lake and rail route from Eastern Canada to Winnipeg. Even before the railway finished building its main line across the country, branch lines were being built to capture the revenue needed to finish the project. Emerson was desperate to expand its railway connections; a traffic bridge was built across the Red River to compete with West Lynne and various railway companies were created on paper. The intentions of the C.P.R., or ‘the Syndicate’ as it was known, with regard to branch lines in southern Manitoba first appeared in the Emerson paper, The Southern Manitoba Times, on July 15, 1881:“From information we have received we are led to believe that the construction of the ‘line’ of the Syndicate will be commenced immediately. The new road connects with the C.P.R. about sixteen miles west of Winnipeg, near Headingly, and strikes a straight line between ranges 1 east and 1 west. It passes Morris, the nearest point it gets to the river about six miles to the west, in the vicinity of Lowe Farm. At the Boundary Line it is distant from West Lynne some 15 miles, crossing the Boundary Line on Section 5, tp.1, range 1 west of which section the Syndicate have lately bought the south half.”10

Construction of the Southwestern and Pembina Mountain Branch of the C.P.R.11 proceeded rapidly not only south to the U.S. border but also west through the northern part of the West Reserve from a junction near the Mennonite village of Rosenfeld. By late 1882 the rails had reached what would become the town of Gretna with the western portion of the line reaching its temporary terminus at Manitoba City (Manitou) when winter set in.12

In the western part of the reserve the town of Stephen sprang up in matter of months in the fall of 1882. The C.P.R. constructed a siding and soon three stores and a hotel were built. Mennonite farmers responded immediately and were delivering enough grain to Stephen that three car loads were shipped daily in March 1883. The C.P.R. was, however, ruthless in its approach towards speculators and fully aware of its power to make or break towns. The company was also quite willing to have site selection for stations result in profit for the company. In 1883 the company established its own townsite a few miles down the line from Stephen at the base of the Pembina Escarpment on the banks of the Cheval (later Dead Horse) Creek.13 The creation of Morden along the railway tracks meant the end of Nelsonville and Mountain City. Mountain City moved its buildings into Morden and in spite of considerable effort and political pressure to have its own railway, by 1884 buildings from Nelsonville were also arriving in Morden.

In Gretna the Ogilvie Flour Milling Company built the first of the familiar style of elevator that would come to dominate the Canadian West. Competition between the C.P.R. and the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway, whose terminus was now at Neche just across the border from Gretna, was intense. The Manitoba Free Press correspondent reported in the fall of 1883 that “the C.P.R. Co. refuses to send grain south even when billed to the southern road, and train loads of grain are sent north to Winnipeg.” The writer went on to suggest it was all part of the plan to “boom” the Canadian main line. The correspondent was also indignant about the tariffs: “The utter idiocy of trade restrictions is well appreciated in towns on the boundary. To describe how the tariff smells in the nostrils of the farmers and traders, who most do congregate at Gretna, would require more space than I can claim.”14

Unlike much of the building of the C.P.R., the branch line that came through the West Reserve was not built through unsettled lands. On the eve of the railway’s arrival there were 53 villages and a population of 3,692 in the West Reserve.15 Mennonite settlement had also not been premised on their being a railway. The Southwestern and Pembina Mountain Branch changed the West Reserve landscape dramatically and totally reoriented the patterns of traffic and trade that had characterized the first seven years of the reserve’s existence. After the demise of Stephen, Morden became the preferred centre for the western part of the reserve, while Gretna enjoyed the business of the central and eastern Mennonite village farmers. Emerson attempted to pursue a solution to its sudden isolation from the West Reserve market. The town negotiated an agreement with the C.P.R. to build a bridge over the Red River for a ‘loop’ line that would connect the town with the Southwestern and Pembina Mountain Branch at Rosenfeld. Although the bridge was started and a line graded and rails laid, “it had been made very clear by [W.C.] van Horne…that the bridge had to be constructed and the right of way through the city purchased by the time track arrived at the city limits.” When the rails reached Emerson in September 1883 the bridge was not ready and the C.P.R. began immediately to tear up the tracks for use elsewhere. By 1885 Emerson was forced into bankruptcy with many of its formerly prominent merchants now established in Gretna and to a lesser extent in Morden.16

However, as the following map illustrates, the location of the two railway towns of Morden and Gretna did not entirely solve the problem of rail access for West Reserve farmers. The C.P.R. came to realize that for farmers to load their horse drawn wagons with grain, make the trip to the elevator, pick up supplies, do their banking and other business in town and return home in time to do chores, the maximum distance between towns could be about five or ten miles.17 Gretna’s five-mile radius was bisected by a hardening international boundary, while Morden’s covered a good deal of the sparsely settled Pembina escarpment. The heart of the West Reserve was outside the optimum catchment area for both towns.

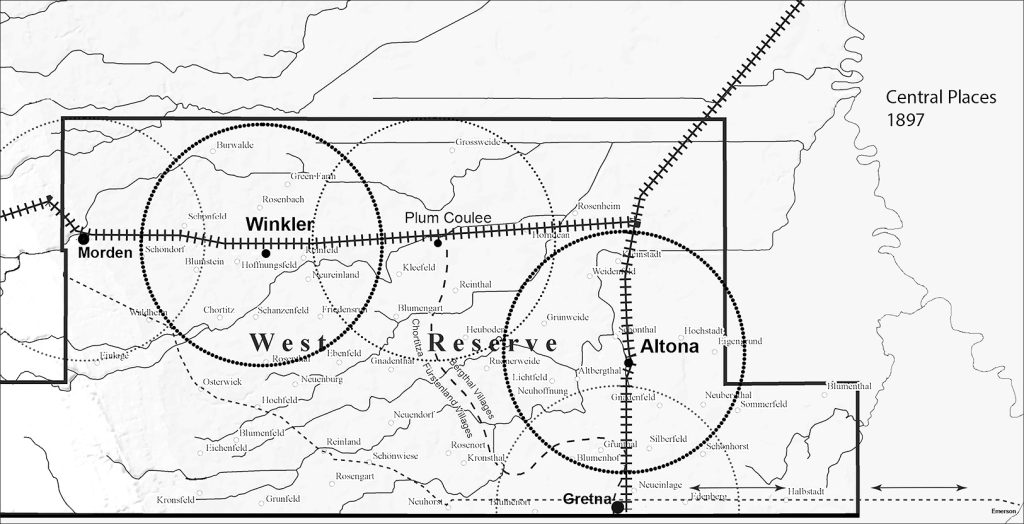

New Places, 1888–1895

Even with only two grain delivery points, the arrival of the railway dramatically boosted wheat production in the West Reserve and almost immediately Mennonite farmers began clamoring for sidings closer to their villages. The C.P.R. and private entrepreneurs responded by establishing four new townsites along the C.P.R. branch line between 1888 and 1895. In 1888 the townsite of Plum Coulee was laid out some seventeen kilometers (ten miles) from the Rosenfeld Junction and twenty-four kilometers (fourteen miles) from Morden. The town soon became a service center for the central part of the reserve and by 1892 featured a number of businesses, including a grain elevator.18 Much like Gretna and Morden, Plum Coulee’s position as a possible premier service center of the West Reserve was restricted by the poorly drained lands north of the townsite.

Four years after the establishment of Plum Coulee, Valentine Winkler would be successful in persuading the C.P.R. to build a siding near the Mennonite village of Hoffnungsfeld, some twelve kilometers (seven miles) from Morden and fourteen kilometers (eight miles) from Plum Coulee. Valentine Winkler was a businessman and politician who came to the West to work at his brother’s lumberyard in Emerson, and then Gretna and Morden, before purchasing the Morden location from his brother. The idea for a townsite east of Morden likely originated with Mennonite farmers since William Whyte, the Superintendent of the Western Division of the C.P.R. indicates in a letter to his superior, W.C. van Horne, that he received a petition from sixty-eight farmers advocating for a station between Morden and Plum Coulee.19 Much to the dismay of Morden, the town of Winkler began as a 500-foot siding and a waybill office that was initially served by the Morden agent. Morden boosters, some of whom had already experienced the failure of Nelsonville, were appalled at the actions of one of their own and dismayed at the prospect of a new town just down the tracks. Winkler seemed to be ideally positioned to capture the grain deliveries and supply business from the areas of the West Reserve that had been settled first. By October 1893 the Morden Monitor reported that Winkler elevators were taking in six thousand bushels a day while Morden’s take had fallen to 2000 bushels.20 In contrast to the earlier railway towns, Winkler’s first merchant was a Mennonite, Bernard Loewen, reflecting the trend of Mennonites slowly accepting and adapting to railway towns in their midst.

Even though it was a boon to area farmers, the establishment of Winkler would deal a blow to Morden and Plum Coulee; in the case of Gretna, the challenge would come with the creation of Altona. In the summer of 1895, the C.P.R. began building a spur just north of Gretna and by fall a new town had been laid out. By January 1896 there were three elevators and a number of stores. One historian suggests the creation of Altona came because of the requests of area Mennonite farmers, “who had been clamouring for another depot on the Southwestern Branch for years,” and “were overjoyed when their request was finally granted.”21 Altona quickly became a major centre and while Gretna held on to the loyalties of some farmers it began to gradually decline in importance. The creation of new towns with overlapping hinterlands shifted the West Reserve’s geography again. By 1897, some five years after its founding, Winkler was emerging as the dominant railway town of the West Reserve. Wheat deliveries to Winkler had exceeded both Morden and Gretna. In the case of Altona, just two years after its founding, it had attracted almost as much wheat as Plum Coulee. In 1897, wheat deliveries to Winkler were 500,000 bushels; in comparison deliveries to Morden and Gretna were 410,000 bushels combined.

As had happened when the railway first arrived in the West Reserve the creation of new railway towns set off a flurry of activity among merchants and equipment dealers. For them questions immediately arose about whether their fortunes would improve if they moved to the new town. The same merchant names that had been in Gretna and Morden began appearing in Plum Coulee, Winkler, and Altona. Otto Schulz, a former partner of Gretna businessman Erdman Penner, and his brother-in-law H.P. Hanson owned stores in Plum Coulee and Morden. In 1894 they moved the Plum Coulee store to Winkler and closed the Morden store. They sold out to Ernest Rietze and Max Heyden in 1897. Rietz had worked for Schultz in Gretna, while Heyden had been a Gretna implement dealer.22

Too Many Railways, Too Many Towns, 1895–1939

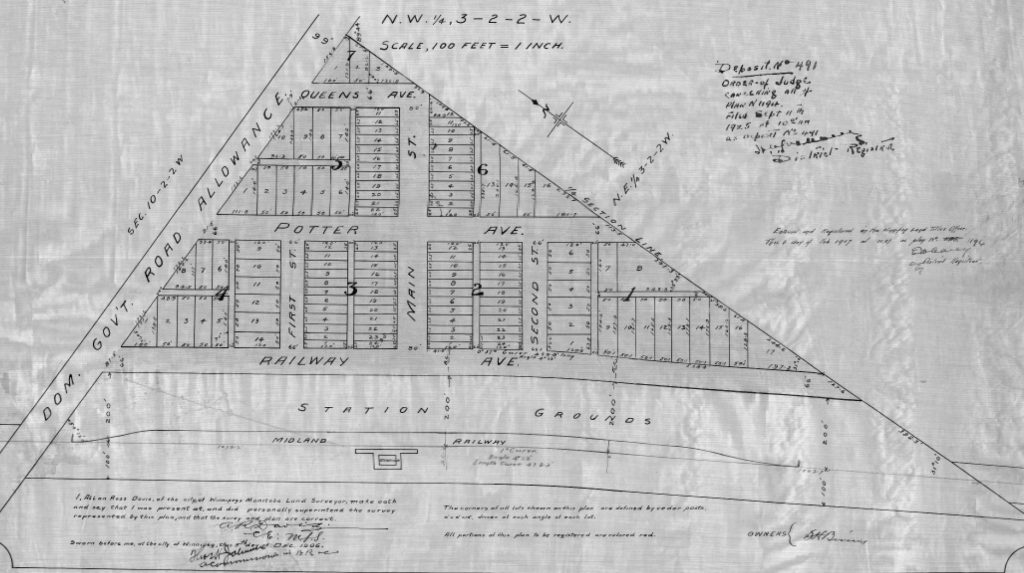

Altona was the last of the major railway towns built in the West Reserve to have a lasting significance. The era of railway building would, however, not reach its peak until the first years of the new century. In 1903 the Midland Railway Company of Manitoba was incorporated as a partnership between two American railway companies, the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific.23 The Midland Railway constructed two lines through the West Reserve. One line originated at Portage la Prairie, went through Kronsgart, just north of the reserve, south to Plum Coulee and then connected to the Great Northern Railway at the border at Gretna. The line was completed in late 1906 with passenger service beginning in early 1907. The other line completed a year later went from Morden to Haskett and then on to connect to the U.S. railways at Walhalla, North Dakota. On July 1, 1909 the Midland Railway Company was purchased by the Great Northern but would retain its name.

As Bruce Wiebe has outlined, although few properties along the company’s rail lines were actually sold to residents or businesses, there was considerable speculation and land dealing associated with the potential townsites along the Midland rail lines. New townsites along the eastern section were planned at Bergman, just west of Altona, while the western section envisioned the townsites of Haskett at the U.S. border south of Winkler and Glencross, west of the West Reserve village of Chortitz. The McCabe Brothers from Duluth, Minnesota saw the new lines as an opportunity for them to get into the Western Canadian grain market and the envisioned townsites invariably had properties in their name for possible agent residences and elevators along railway right of ways.24 McCabe elevators sprang up in the West Reserve along the Midland rail lines at Bergmann (25,000 bushels), Glencross (23,000 bu.), Gretna (25,000 bu.), and Haskett (23,000 bu.).25 John Warkentin’s study concludes that the Midland Railway lines “were unsuccessful.” By the time the Midland Railway Company arrived on the scene, the towns along C.P.R.’s branch line had been there for ten years in the case of Altona and twenty-four years in the case of Morden, and the location of the lines and projected stations provided limited improvement to rail access. The line going from Plum Coulee to Gretna was abandoned and the tracks removed in 1926 while the Morden to Haskett line managed to remain in limited operation for another ten years. Warkentin discounts any effect of the Plum Coulee to Gretna line on West Reserve trading patterns and suggests the Morden to Walhalla line had some effect on the West Reserve because of the establishment of Haskett as “a satellite of Walhalla.” Local farmers shipped their cream to Walhalla creameries through Haskett and although the town never had more than one hundred residents, it was also a service center for farmers in the southwestern corner of the West Reserve and non-Mennonite farmers from townships one to five just outside the reserve.26

A similar fate awaited new towns and sidings along the Southwestern and Pembina Mountain Branch. Although the C.P.R. had surveyed the townsite of Rosenfeld at the junction where the line went to Gretna and west as early as 1891, the lack of drainage to the north and presence of Plum Coulee ten miles away prevented Rosenfeld from becoming a major centre. In 1911 the C.P.R. was finally convinced to construct a siding at what would become Horndean, a short five miles down the track from Rosenfeld and only four miles from Plum Coulee. As early as 1908 C. W. Wiebe and his brother John had organized a petition to have a siding built on their land beside the tracks. Horndean came into existence alongside the siding, but it was too late and too close to Plum Coulee to become a major centre.27

For the most part, trains have left our consciousness as determinants of where we live and do our shopping. Even for farmers the truck has become dominant and the location of the nearest railway line less important. Passenger service in the West Reserve came to an end in the 1950s and gradually the train stations disappeared due to demolition or were moved to become museums. The arrival of the diesel locomotive around the same time as the end of passenger service meant that water towers, roundhouses, and the smoke and hiss of the steam locomotive also faded away. The railway had its most dramatic and lasting effect on the geography of the West Reserve between 1882 until the First World War. In the space of the fifteen years between 1880 and 1895, Mennonite farm families that had faced two and three day trips by ox-drawn wagons to bring their first surplus grain to Emerson, could hitch up their horses in the morning, deliver their grain to the elevator in Winkler, Altona, or Plum Coulee, do their other business and be home in time for evening chores. A trip to Winnipeg, previously a major undertaking, became easily possible. In 1894 one could board the train in Gretna at 10:30 and be in Winnipeg for a late lunch at 12:50 every day except Sunday.28 Winkler and Altona, the largest service centres in the West Reserve today, grew because of the railway.

Mennonites of the West Reserve had an ambiguous relationship with the railway and the towns it brought with it. For the most conservative, living in a railway town conflicted with their sensibility of being separate from the world, while at the same time they thrived on the railway’s benefits, which brought them supplies and took their grain to the market. For the more liberal-minded they soon adapted to the business opportunities and employment that came with the railway town. By the time Winkler and Altona made their appearance Mennonite businessmen and merchants were an integral part of community life in both places, and eventually both became ‘Mennonite’ towns.

While the ordering of the prairie landscape was dramatically shaped by the railway in the years of European settlement, the influence of the railway on the West Reserve has some unique features. The railway did not stimulate the settlement of the West Reserve, but rather the development of railway lines responded to pre-existing settlement. And yet, the railway still reoriented West Reserve space dramatically over a fifteen-year period. The arrival of the Southwestern and Pembina Mountain Branch of the C.P.R. was a tremendous economic stimulus for West Reserve farmers, even though their relationship with railway towns was somewhat ambivalent. Ironically, perhaps, the more conservative Mennonite area along the western side of the reserve who were most reticent to have too much to do with railway towns, stimulated the creation and growth of Winkler, ultimately the largest West Reserve centre.

- The Indigenous view of their origins in contrast to migration theories that account for their presence. The phrase is also the title of a popular illustrated history. Arthur J. Ray, I have lived here since the World began: An Illustrated History of Canada’s Native Peoples, (Toronto: Lester Publishing and Key Porter Books, 1996). ↩︎

- Andrew J. Schmidt, Andrew C. Vermeer, Daniel R. Pratt, and Betsy H. Bradley, “Minnesota Statewide Historic Railroads Study Project Report,” Minnesota Department of Transportation, June 2007, 82, https://www.dot.state.mn.us/culturalresources/docs/rail/rrfpr.pdf ↩︎

- James McClelland, “Emerson during the 1880s, the Town, the People and the Railroad,” in James McClelland and Dan Lewis, eds., Emerson, 1875–1975: A Centennial History (Emerson: Town of Emerson, 1975), 12. ↩︎

- Father Theobald Bitsche as quoted in F. G. Enns, Gretna: Window on the Northwest (Gretna: Village of Gretna History Committee, 1987), 9. ↩︎

- Annual Report of Dufferin Agent,” Sessional Papers (No. 10), 43 Victoria, 63. ↩︎

- Conrad D. Stoesz, “The Post Road,” in Adolf Ens, Jacob E. Peters and Otto Hamm, eds., Church, Family and Village (Winnipeg: Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 2001), 85–86. See also: Albert Siemens, “William Brown, Innkeeper on the Post Road, 1880–1894,” Preservings 36 (2016): 44–50. ↩︎

- John H. Warkentin, The Mennonite Settlements of Southern Manitoba (Steinbach: Hanover Historical Society, 2000), 97. ↩︎

- McClelland, 19. ↩︎

- McClelland, 18. ↩︎

- As quoted in Gerhard Ens, Volost and Municipality: The Rural Municipality of Rhineland, 1884–1984 (Altona: R.M. of Rhineland, 1984), 22. ↩︎

- Later this branch would be extended to LaRiviere and would be known as the LaRiviere Subdivision. ↩︎

- Pembina-Manitou 100th Anniversary (Steinbach: Pembina-Manitou Centennial Committee, 1978), 46–47. ↩︎

- Bruce Wiebe, “Abandoned Railway Town-sites or Stations in, or near the Mennonite West Reserve,” Preservings 31 (2011): 34–36. ↩︎

- Manitoba Free Press, November 29, 1883 as quote in Enns, 37. ↩︎

- Ens, 21. ↩︎

- McClelland, 23–26. ↩︎

- David Butterfield, Railway Stations of Manitoba: An Architectural History Theme Study (Winnipeg: Government of Manitoba, Historic Resources Branch, n.d.), 13. ↩︎

- Ens, 70. ↩︎

- Hans Werner, Living Between Worlds: A History of Winkler (Winkler: Winkler Heritage Society, 2006), 15 ↩︎

- Morden Monitor, 12 October 1893. ↩︎

- Esther Epp-Tiessen, Altona: The Story of a Prairie Town (Altona: D.W. Friesen & Sons, 1982), 53. ↩︎

- Werner, 25. ↩︎

- Christopher G.L. Mcombe, “Network Evolution: The Origins, Development and Effectiveness of Manitoba’s Railway System,” M.A. Thesis, University of Manitoba, 2011: 44. ↩︎

- Wiebe, 36–39. ↩︎

- “Manitoba Business: McCabe Elevator Company / McCabe Brothers Grain Company / McCabe Grain Company,” Manitoba Historical Society, http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/business/mccabegrain.shtml ↩︎

- Warkentin, 186. ↩︎

- Cleo Heinrichs, Marie Friesen and Anne Wiebe, eds., Horndean Heritage (Winkler: Horndean Heritage Committee, 1984), 131. ↩︎

- Waghorns Guide, 1894, http://eco.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_04859_131/30?r=0&s=4 ↩︎