The One Who Remained Behind

Dave Loewen

When Abraham and Maria (Eitzen) Loewen immigrated to Canada from Pretoria, Orenburg, Russia in 1926, one member of their family chose to stay behind.1 Jacob Loewen’s promise to follow later was never realized. This is his story.

Academia Over Farming

In the spring of 1922, Jacob Loewen, along with brother Abram, graduated from the school in Pretoria. Unlike Abram, Jacob wished desperately to continue his studies in the city, and he received encouragement from his Russian teachers, who saw promise in him. Unfortunately, his father did not share that sentiment; he needed his boys at home to help with farm work. Also, Mennonites tended to believe that city life would draw people away from God.

Thanks to Jacob’s insistence, Abraham relented despite these obstacles; however, he made Jacob promise not to expect any financial support from his parents. With the help of his teachers, he gained admission to a vocational school in Samara where he was given a scholarship as well as room and board. His mother packed a food parcel (some pastry and several kilograms of millet) and his father paid his third-class railway ticket. In Jacob’s words, “I went out into a strange world ‘to swim on an open ocean.’”

As he remembered: “Our scholarship consisted of getting five rubles worth of produce, which we would get monthly in the kitchen. Our food was one kilogram of rye bread in the morning and evening; lunch was soup with some pieces of potatoes and a little fish tail in it. It was only enough that we would not starve. The millet from my mother helped me a lot and I managed to survive.”

Jacob’s student life was quite relaxed. He became involved in theatre and student life and developed a reputation as a mediator; student issues were brought to him for arbitration. This caught the attention of Communist youth organization, the Komsomol, and the leaders invited him to become the secretary of the local chapter, which was only beginning to consolidate itself.

In the spring of 1924, Jacob graduated from the vocational school in Samara. His success in school and his active participation in public affairs resulted in an opportunity to continue his education in the Caucasus. Jacob arrived in Vladikavkaz with very little to live on. He was able to secure a job working in the school cafeteria, but only one day per week. “When serving in the kitchen, I usually had eaten enough for two days. Since there were many starving students who wanted work in the kitchen, I was only allowed to work one day per week. There were days when I had nothing to eat, but life was interesting.”

Jacob’s life was turned upside down when the school was suddenly closed. With most students moving on to school in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Jacob had difficulty deciding what to do because of the uncertainty of a scholarship. Additionally, he had lost his interest in history and made the decision to change to the physical sciences, even though he found the foundational courses – math, physics, and chemistry – more difficult. He applied himself to the challenge and, with the assistance of fellow students, he succeeded in being accepted into the Faculty of Natural Sciences, which allowed him to remain in Vladikavkaz.

Jacob studied under the inspiring leadership of Professor Smirnov; this led him to the decision to become a geologist. Jacob became a technical assistant, which helped with his purchase of expensive text books. One book alone cost 7.50 rubles, half his stipend. Initially, students could order books from Germany, but that was soon forbidden. Since many teachers did not order any books, Jacob ordered books under their names. He developed a good German-language library on geology, which greatly assisted him in his academic research.

Staying Behind

Given the extent to which Jacob had become involved in both his studies and in student life in general, it is not a surprise that he had no appetite to join his parents and siblings in leaving for Canada, with only its promise of farming and hard work. Upon learning of his family’s pending departure, he shared his thoughts in a letter to his parents: “Dear Parents: Your letter surprised me a little. I can see that your plans for departure are serious, and that you will soon be leaving. I want to heartily wish you a safe journey and a new and better home country. I, however, wish to remain here in my old home country. Why? Early on I set myself the goal of learning and seeing much. I was let go quite easily in 1922 when I travelled to Samara. In the subsequent three long years I starved myself, so to speak. I denied myself all pleasures to get an education. I lived like a beggar away from home, experienced hunger and stress, and now, suddenly, just as I’ve reached my goal, that point where I am beginning to learn significant material – to turn around and say that all that struggle was for nothing, to leave everything, and to travel to a strange land and be shackled to work I don’t like for the rest of my life – I can’t do it.”

His last year of study was an important milestone in Jacob’s academic career. Shortly following an all-Russian meeting of geologists in Tashkent, Professor Smirnov returned home and was put in charge of the geology faculty, which had an opening for an assistant. Jacob was one of three candidates who wanted the position – all qualified. As Smirnov did not want to part with any of the three, it was decided that all three would go and live on one person’s salary – 180 rubles. Officially, Jacob was identified as the assistant, because if he did not work, he would have had to join the army. The other two were exempted from service because of their qualifications. In the middle of January 1929, in the company of Smirnov, Jacob and his two colleagues set off for Samarkand in south-eastern Uzbekistan.

Transitions

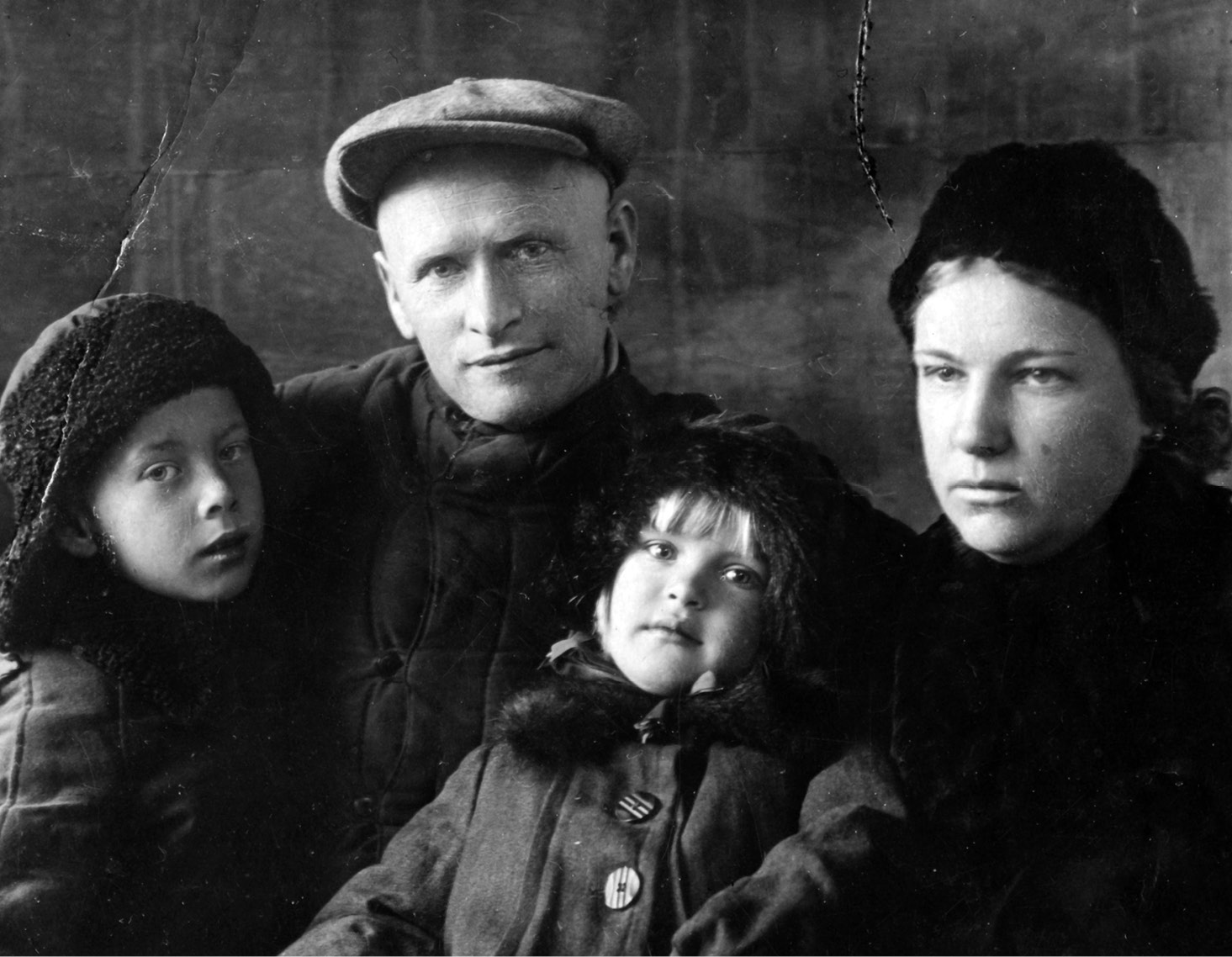

In 1932, Jacob was promoted from assistant to assistant professor, which improved his financial position. That same year, he married Lyuba Ivanovna Viktorova, the daughter of a factory worker and a student from the chemistry faculty. In 1933, Lyuba gave birth to twin boys. One died in infancy; the surviving twin was named Ernst. In 1935, a daughter was born: Eleonora Margareta. Both children pursued higher education: Ernst in geology and Ella in music.

In 1936, Jacob’s work lost the interest of local geologists, and therefore, he applied and was assigned to the Institute of Mineral Raw Materials in Moscow. The authorities were well-acquainted with his work in Samarkand, and particularly with his inquiry into Iceland spar (a nearly translucent calcite useful in the production of optical instruments) which was in great demand by Soviet industry. He was soon appointed as a “commander” in the Tadzhiko-Pamirskoy Expedition.2 Jacob recalled, “To me it seemed as though I was in a fairy tale.” Jacob continued his search not only for Iceland spar, but in 1939 expanded his investigations to include optic fluorite. In 1941, however, his work was disrupted by the Second World War.

Soviet Police Investigations

Although Jacob’s ethnic roots had initially caused him no concern, this changed dramatically during the 1930s and, later, during the war. As he remembered, “I paid a lot of attention to the police. During the first year in Samara and in Vladikavkaz, I had nothing to do with them. As a German, I never felt threatened, but felt like a full Soviet citizen. I was not a member of the Communist Youth Organization, but my influence never suffered. This continued up to Samarkand. In 1935, the political climate in the country began to worsen. They started to watch everyone, especially Germans, who were treated as spies. In every organization there were men who worked for the police. They investigated everyone. Everyone had to be careful of what he said. An acquaintance of mine, a past chairman of a soviet, had been arrested and sentenced for a speech he had made. He had been declared an enemy of the people, which was grounds for arrest. It was evident that everyone was being watched. Everyone had to submit a biography which was checked by the police, and every little thing was investigated.”

In the spring of 1937, while submitting his regular report to the authorities, one official questioned another regarding Jacob’s trustworthiness. The other vouched for him, saying that Jacob had been honest in admitting in his report that he had relatives outside the USSR, and that was good with him. Jacob was not reported. On another occasion, representatives of the university asked Jacob about his relatives in Canada and if he had been corresponding with them. Jacob replied that he had, but that he had received no letters for a year. When asked why not, Jacob had replied that he wanted to have no difficulties with the authorities – to which the official smiled and the matter was put to rest.

Even though Jacob had begun to feel more positive about his relationship with the authorities, including the police, there was still one more challenge to come. He was often called by the police to give reports about the teaching staff. Despite all the questions, they could not get anything from him. The chief of police even summoned him to the city for questioning. He was accused of not wanting to help them against “enemies of the State.” “I told them that I was not aware of any and I did not want to lie. He warned me and bounced the pistol on the table and said, ‘If you will not help us, we will put you into jail.’ I affirmed to him that my conscience does not allow me to give false accusations. If your conscience urges you to take me to the cellar, do as your conscience dictates. The conversation was terminated; I felt that my fate was sealed. I would be arrested shortly. Lyuba and I began to prepare for this event. We could not sleep at night. Any car that stopped close by scared us. But nothing happened.”

The Labour Army

Given the fact that Jacob was of “German” descent, it should not be a surprise that the Second World War changed his daily life significantly. He was removed from the work he had been doing and was prevented from settling anywhere. He did, however, find work at home related to the geological search with which he had been involved. He and his family were soon sent to the Samarkand region, where they had to become used to living in close quarters. Very shortly after arriving, Jacob received orders to appear at Samarkand to join German expatriates fifty years of age and younger. They were transferred to Cheliabinsk (a city in west-central Russia, close to the Ural Mountains) and turned over to the police, who took them to a camp surrounded by barbed wire and under guard. It was like a prison. Jacob remembered that they were placed in uncomfortably damp earthen huts that had recently been built.

Jacob found himself, and the others, working in a stone quarry. Jacob remembered: “The work was just like in the book by Solzhenitsyn – One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. It was just like in a prison, perhaps worse. In the morning we would usually see the bodies of the dead, who had worked up to the last day until they collapsed from starvation. Shortly after waking up, and approaching the registration, we would see a list of names of those sentenced to be shot that day. They tried to keep us down and discouraged as much as possible.”

Jacob soon realized that hard labour could be his ultimate undoing; with help from a close friend, he was able to secure a job in the kitchen. He described his kitchen assignment as follows: “My work involved going to the bakery in the morning with a team of horses. There I would receive the necessary 60,000 loaves of brown bread for the camp. The number of loaves was strictly controlled. I signed for the bread in the bakery and upon my return, my three bread cutters and I cut the bread according to the office records. The bread was cut according to a set scale of 0.4, 0.5, 0.8, and 1.0 kilogram. In two hours, we had to have 10,000 rations ready. I had to distribute the bread to the brigades.”

Even this work had its dangers, as he discovered when a discrepancy arose over rations distributed and remaining. The threats of jail and even execution were real. Recognizing the danger, Jacob successfully requested another transfer – this time to the building maintenance department, where he was put in charge. Jacob recalled that he always had good memories of his superior at that camp, who was consistently a fair man.

In the summer of 1943 hunger stalked the camp and Jacob realized he was losing weight rapidly. He asked Lyuba to sell anything possible to acquire food. She managed to send a parcel of “produce” which was very helpful. Again, Jacob managed to get himself transferred out of this camp to another and this time found himself doing what he enjoyed: geological research.

His new task was to locate sources of water, sand, and loam for construction purposes. No wages were paid; instead, rations were given based on work completed. This new assignment brought with it a sense of independence and freedom, as well as good relationships with those in authority. For several winter months he worked in a factory producing gun powder. The temperature dropped to -45 degrees, something Jacob had not previously experienced.

Even though a certain degree of freedom was evident, the labourers worked under the watchful eye of the police, and more than five prisoners were never allowed to congregate in one place. It was now 1944. The labourers’ food consisted of dry rations, but since they enjoyed a degree of freedom, he and his work companions decided to venture into surrounding villages to trade for food with anything they could spare. They gleaned in fields already harvested, finding such things as potatoes and carrots. They even managed to build a house and obtain cash with which to buy their daily milk.

The Post-war Years

The end of the war did not mark the end of his assignment to the Labour Army for Jacob. He was given permission to go home to Samarkand for a month in 1946. Jacob’s arrival at home was both unexpected and hard on Lyuba. The family had moved to smaller quarters and she was having difficulty meeting everyday needs with her office job, working for a chemist. Jacob was offered a job, if he should be given his freedom, with the MVD (successor to the NKVD) in building maintenance. This was refused. In Jacob’s words, “My situation was worse than before.”

There was no doubt in Jacob’s mind of the importance of the work in which he had been involved. He resolved to appeal to the head of the MVD, Lavrentiy Beria, and if that failed, to apply directly to Stalin to permit him to return to Samarkand to resume his work. That was early in 1947; on August 12 of that year, he was summoned by phone to appear at the head office within fifteen minutes. His superior asked Jacob if he had applied to the highest offices in the land, to which he replied in the affirmative. He then demanded that Jacob sign a release form and presented him with an order from the MVD to proceed to Samarkand. When he asked for his permit to leave the area – which was a formal requirement – he was informed he did not need one. This fact alone convinced Jacob that there was no doubt any longer that he was trusted.

“Freedom”

Jacob’s perspective on those lost years: “Now I was free. I could hardly believe it. I tried to get away before they could change their minds. Miraculously and with great effort I went home. Thinking about my life in the Workers’ Army [Labour Army], it had not been too bad. It was a good move to get away from the stone quarry. I would not have survived in that place. As bread cutter, I had kept my physique in a normal shape. In my research work with the engineers, it had been good, and the field work in search of water gave me a lot of experience in this area. I relied on this experience when I lectured in the university on the practical applications of geological searches. I lost five years of my life, but compared with other citizens, who lost their lives, their loved ones, and all material belongings during the war, I was lucky. I am alive, and my family is intact. The economic loss is of no consequence and did not matter much.”

Jacob soon attained a position as lecturer in the geology department at Samarkand. Notwithstanding Jacob’s stature at the university, as an ethnic German he was under constant surveillance by the MVD and was required to keep them informed of any movement away from the city. His mail was censored. In a letter from his father, however, was an enclosed note from the censor, and Jacob was finally made aware of the answer to an old family mystery. The censor in question introduced himself as a former close friend of Jacob’s older brother Johann. He revealed, for the first time, that Johann had died of typhus in Sochi. Finally, there was closure for the family regarding Johann’s disappearance and death, approximately twenty-five years after the fact.

After Stalin’s death, life for Jacob normalized. The MVD informed him that he was trusted fully. He was the recipient of no political opposition anywhere. During the 1960s, the geology faculty closed, and Jacob became dean of the Faculty of History and Geography. In 1950, the authorities allowed Jacob to start building his own home. On their lot, Jacob and Lyuba had apples, cherries, peaches, and a few varieties of grapes, providing all the fruit they needed. Jacob’s wages allowed Lyuba to quit her job, allowing her to focus on homemaking.

As he reflected on his life, Jacob wrote, “Looking into the past of my life, I must admit it was good. I entered the world just at the right time. Four years earlier or later and I would not have been able to leave the village. The Revolution came during my youth and I had a plan to get away from the role of a farmer. I wanted to see the world. This brought us into the village library. The Revolution also brought two sisters into our village – Helen and Maria Petrovna Potemkin. The relationship with them opened a new world to me and brought wings into my thinking. In the fall of 1922, I left my village and stepped into a strange city.”

Over the years, whenever we thought of our Uncle Jacob in the Soviet Union, we only focused on the tragedy of a son who had become trapped behind the Iron Curtain, never to be reunited with his parents. We lacked the full picture of his life and, particularly, the family he had nurtured and loved, along with the challenges he faced. For me at least, the thought that Jacob had lived a fulfilling life was not considered. The opposite appears to have been the case; it is quite clear that of all the Loewen siblings, Jacob lived the most interestingly diverse life. His whole life appeared to be an adventure. It certainly was not an easy life, but Jacob had successfully navigated his way through a maze of challenges that most others might very well have failed at.