Perseverance and Family: The Journey of the “Schulz Clock”

Helga Elizabeth (“Liza”) Kroeger

I distinctly remember the moment this clock came into my life. It was in the summer of 1964. We lived in Winnipeg, and my parents, the late Arthur and Elfriede Kroeger, had decided it was time for another family road trip. Our destination was Vauxhall, Alberta, a town with fewer than a thousand people. My mother loved to travel, and it didn’t matter that we’d be camping along the way. Our once bright red, now very faded, tent, five air mattresses, and five sleeping bags were tightly folded and fitted into a wooden car-top carrier made by my father’s own hands.

By sunset on the second day we had arrived at uncle Peter’s farm and I can’t remember a lonelier place. Not that he was alone, living with his wife, aunt Irene, four lively and fun-loving teenagers of indeterminable ages, and a collection of farm animals. I remember thinking, what fate had befallen the Schulz family that they should be stranded in such a place? (My apologies to any southern Albertan readers; the beauty of this place was lost on me at the time). As a pre-adolescent, needless to say, this summer trip was straining. Adding to my discontentment, on the day we said our goodbyes we had to make room in the trunk of our 1960 Ford Falcon (with no air-conditioning) for two dusty old crates containing rusty clocks and pendulums. As my father took out our travel bags and stuffed them into the already crowded back seat with me and my two sisters, I was not amused. On the long road back, did my father attempt to impart to his daughters the story of Mennonite clocks? I believe so as he was always telling stories about life in the Mennonite colonies of the Russian empire. But in that moment, I did not make the connection between these stories and the clocks in our trunk.

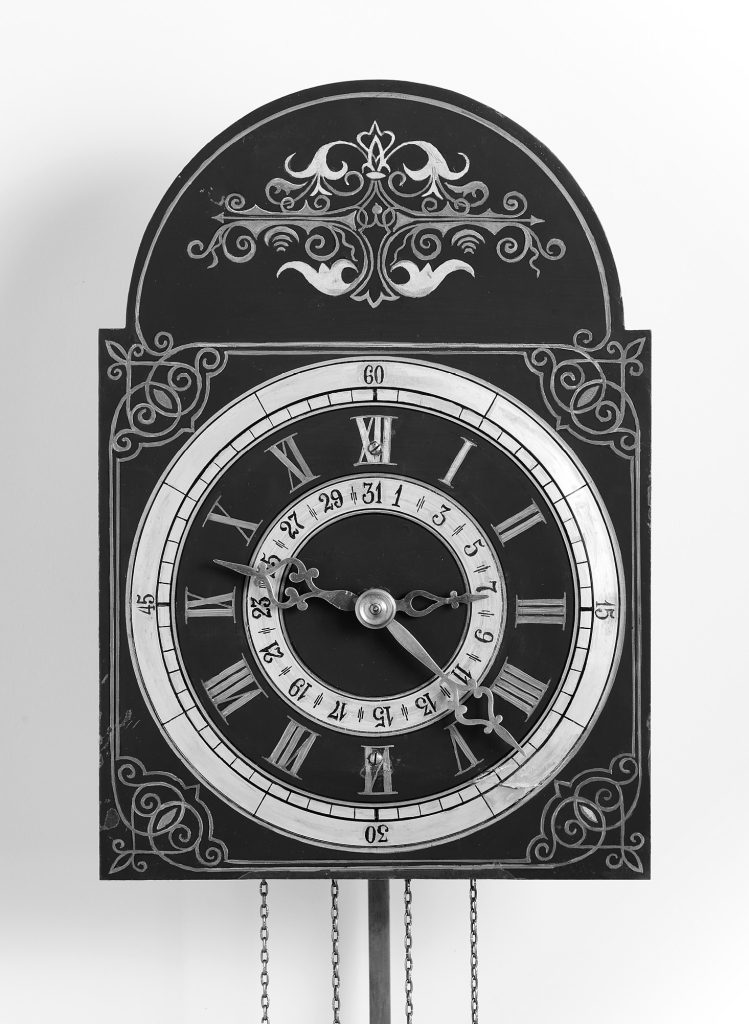

I cannot recall much about my father’s restoration of the “Schulz” clock after its journey to Winnipeg. Decades later, I discovered the tracing that my father must have made before he began repainting the clock dial. Where did he find the pattern that he would use to restore this clock? Did he base the restoration on his childhood memories, when he saw it as a boy hanging in the two-story mansion of his maternal grandmother, Anna (Zacharias) Schulz? The clock had been a wedding gift from the Schulz family, made with care by David D. Kroeger, his paternal great-grandfather, a clock maker in Rosenthal.1

From my father’s notes, I realize now that this was the first of many clocks that he would restore. He spent an inordinate amount of time in preparation: his study on parchment alone attests to his great care and attention to detail. His dedication speaks to the responsibility he must have felt as the heir to the Kroeger clock-making legacy. Looking at the clock, I imagine that the “regal” motif on the clock dial of golden scrolls against a dark burgundy background appealed to his sensibilities. There was always a hint of fancifulness in my father’s work.

And so, the Schulz clock took its place in our family home. At first, it occupied a rather mundane position in the basement; in our next house, it would become the centre attraction in the entrance hall. Always ticking, as the pendulum swung back and forth, always chiming, as the bell struck the hour, this clock witnessed the story of its owners: from its beginnings as a wedding gift for my great-grandparents, through the calamities of war and revolution in the southern Ukrainian steppe and the strains of the shipboard journey to the “New World,” as it arrived in the safe haven of the Canadian prairies.

Although Kroeger clock-making had its beginnings in the Vistula Delta, it flowered in the town of Rosenthal, in the Khortitsa colony. Johann Kroeger (1754–1823) migrated into the Russian empire in 1804 and his descendants would continue the trade, making many of the clocks that survive today—estimated to be many several thousand. Distinctive clocks were also made by other Mennonite clockmakers, such as Peter Lepp, Gerhard Hamm, and Kornelius Hildebrand in the Khortitsa colony, and by the Mandtler family in the Molotschna colony.

Like the Schulz clock, which can be seen in the exhibition, “The Art of Mennonite Clocks” at the Mennonite Heritage Village in Steinbach until April 2019, many of the timepieces were commissioned by parents as wedding gifts for their children. They became cherished heirlooms, passed down through generations. As families immigrated, they carried these clocks to North, Central, and South America, despite being heavy and cumbersome. In their new countries, these clocks made a house feel like a home as their ticking and ringing accompanied the domestic life of generations of Mennonites.

These clocks are an important part of Mennonite material culture. As Kathleen Wiens, exhibition developer for the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, writes, “Physical objects are where we find evidence of the resilience and creativity that not only brought us through the challenges of history, but also brought joy into people’s lives and homes. Tangible heritage is not the quaint side projects of our ancestors: it is our people embedding their priorities, experiences, hearts, minds, and spirits into our physical world.”2

The Schulz clock has its own story of hardship and strength. From the “bloodlands” of eastern Europe to Canada, the clock journeyed with my great-grandmother who, like so many others, cherished this connection with her past. When the clock was installed in our basement in 1964, safe and sound in suburban Canada, I wasn’t yet a teenager. I was oblivious to its presence, absorbed in my own world, more interested in dancing to the Beatles than in contemplating my family’s past. But children become adults. And adults come to see that the past defines their present and sets the stage for their future. The Schulz clock has been a witness to my journey.

- Arthur Kroeger, Kroeger Clocks (Steinbach, MB: Mennonite Heritage Village, 2012), 104. Until recently, very little research existed on Mennonite clocks and their importance to community identity and historical memory. My father’s book built on the small existing body of literature. His research provided an important step towards bringing attention to the stories of the then known surviving clocks. His extensive travel, documentation, and restoration work resulted in the verification and detailed documentation of at least 250 clocks currently in private collections and museums in Poland, Germany, Russia, Ukraine, Canada, Mexico, Belize, and Paraguay. Some of this research took place in regions now unsafe to access due to on-going conflict in Ukraine. There is reason to believe that many more clocks survived than have been documented, and many more stories of hardship and strength remain undocumented and inaccessible. ↩︎

- ‘‘I Love Stories About People Going Rogue’: 5 Questions with Kathleen Wiens,” Mennotoba, www.mennotoba.com/ i-love-stories-about-people-going-rogue-5-questions-with-kathleen-wiens ↩︎