Revive Us Again: A Brief History of Revivalism in Steinbach

Ralph Friesen

Steinbach has a one-hundred-year history of religious revivalism, dating back almost to the earliest days of settlement. In this article I will sketch an outline of that history and speculate on the influence it has exerted on the town (now a city) and its inhabitants.1

Revivalism began with “The Great Awakening” (1720–50), a series of Christian revivals that swept across Britain and its American colonies, followed by a second Great Awakening (1795–1835), and more manifestations in the twentieth century. The term has the following definition: “Revivalism was an attempt to lift an otherwise routine and often dry, doctrinaire and moralistic Protestantism out of complacency to a more fervent level of faith, by holding a series of revival meetings characterized by emotional crises of faith, effected by strongly worded preaching and rousing music.”2 The whole revivalist impulse was based on polarities, the perception of opposites, an antithesis between saved and lost.3 It is important to note that “revivalism has always assumed that only its own type of religious experience can be perfect.”4

At first glance Steinbach would not seem to have been open to revivalist influences. Practically all the original settlers were Kleine Gemeinde Mennonites from villages in South Russia. All the adults were baptized church members. So why choose Steinbach? For the revivalists, there were two answers to this question: “To awaken us, as children of God, from the lax condition into which we fall again and again and also to bring sinners to Jesus.”5

Steinbach’s original population was, in Leland Harder’s term, kirchliche. According to Harder, this means: “The kirchliche-type is basically a cultural church. Membership tends to be by birth into the religious-cultural community. Church and community become identical. The moral demands made by the church are indistinguishable from the general cultural standards of the community . . . .”6

For some, this situation was not good enough. Even the Ältester (bishop) of the Kleine Gemeinde in Manitoba, Peter Toews (1841–1922), was dissatisfied with the spiritual condition of his own people. He would have agreed with church historian P. J. B. Reimer: “There were too many who thought that a true believer must only fear the wrath of God and live a constant life of penitence and spiritual misery.”7 In material terms the Steinbach settlers exhibited remarkable skills of industry and commerce. But for Peter Toews, such success was just another challenge to spiritual health.

John Holdeman

Toews invited John Holdeman to speak in the East Reserve villages, including Steinbach. Holdeman (1832–1900), a born-again Old Mennonite from Kansas via Ohio, declared that he had been shown in a dream that many Kleine Gemeinde members had not been truly converted upon baptism.8 A completely new start was needed, with each person to be re-baptized before joining the Church of God in Christ.9

On a return visit in December 1881, with his fellow preacher Markus Seiler, Holdeman held meetings at the home of Franz Kroeker. At one of these Peter Toews came under conviction: “A special power gripped me which made my whole body shake and tremble so that I thought the place moved beneath us, and I instantly received a great joy. Having arisen from prayer, the trembling and movement still continued throughout my body.”10 Similarly, Maria Barkman (née Friesen, 1860–1942) testified that “joy unspeakable and glory flooded my soul” upon her conversion.11

Revivalism’s intent was to bring about just such powerful experiences. Toews and other converts were received into the Church of God in Christ through the laying on of hands and baptism by Holdeman. More meetings stretched well into 1882 and many people were converted. In Steinbach, which by then had grown to twenty-eight families with a total population of 128, twenty-two adults were baptized into the new church.12

Psychologist William James has shown that conversion experiences have a psychological structure, beginning with the sense of sinfulness and inadequacy, moving toward a painful surrender of the personal will, and then reaching a sense of inner harmony, understood as forgiveness by and atonement with God. The convert’s perceptions may be enhanced, so that the whole world, especially nature, appears clear and beautiful.13

Such an experience is a crisis in the individual’s life, happening instantaneously. Even if its emotional effects wear off in time—and they do—the individual is marked by the experience, and because of it may make behavioural changes which last a lifetime. Revivalists promoted such experiences as part of a general renewal movement whose membership was based on a personal acceptance of Jesus Christ.14 As such, they can be called evangelisch, contrasting with the aforementioned kirchliche Mennonites.

The Kleine Gemeinde in Steinbach had no counter-punch for testimonies like Peter Toews’s, other than to dig in and become more kirchliche than ever. The old religion would serve as their social and religious blueprint for the next thirty-five years and more.15

But the old religion’s authority had been undermined. Until this point, every aspect of life in Steinbach, whether religion, education, health or commerce, had come under the purview of one Gemeinde. Now there were two Gemeinden, with “one, true church” (Holdeman) alongside another “one, true church” (Kleine Gemeinde). It seems an unconscious decision was made to ignore the logical problem. Yet, the door to other forms of revivalism had been opened.

Rise of the Bruderthaler

In 1886, an impoverished school teacher named Heinrich Rempel (1855–1926) took up residence in Kleefeld. He had emigrated from the Molotschna village of Waldheim, “a hotbed of evangelical revivalism.”16 He began a correspondence with Aaron Wall, organizer of a Mountain Lake, Minnesota Mennonite congregation known as the “Bruderthaler,” or “Brethren in the valley.” In 1895 Wall and itinerant preacher Heinrich Fast (1849–1930) came to Steinbach to teach “repentance and forgiveness of sin.” As a result, a branch of the Bruderthaler church was formed in 1897.17 Now there were three congregations in Steinbach.

Subsequently, Heinrich Fast made frequent visits, winning converts. Then, as early as 1908, George P. Schultz also began conducting revival meetings—or, as they were called in the German-language newspaper reports, Erweckungspredigen.18 Schultz, a graduate of the Moody Bible Institute, was the predominant evangelizer in Steinbach through the 1920s and 1930s. Believers were to “live on fire for the Lord” and turn “the main objective of all that we do as farmers, businessmen, teachers, preachers . . . to [the saving of] souls.”19 His voice was so commanding that when he preached in the church on Mill Street, he could be heard as far away as Loewen Garage on Main Street. It was said that he “screamed the gospel.”20

In that scream was the ideology of D. L. Moody, the father of American fundamentalism.21 Moody preached a literal interpretation of the Bible and the imminence of the Second Coming, to be followed by a thousand-year reign of Christ on earth. He also believed that social problems could be solved only by the divine regeneration of individuals.22 These views found sympathetic ears in Steinbach, despite a certain discomfort with fundamentalism’s patriotism and its support of armed conflict. As historian Frank H. Epp has so astutely observed: “For timid Mennonite people such expressions of self-confidence helped to wash away an apologetic gospel and inferiority feelings, which generations of persecution, isolation and nonconformity had written deep into their souls.”23 And sociologist Calvin Redekop goes further, to suggest that the rejection of tradition and embrace of revivalism contained an element of self-hatred.24

The Kleine Gemeinde had always been wary of unbridled commerce, fearing that it would lead to spiritual decline. The Bruderthaler had fewer qualms. According to P. J. B. Reimer, “The mission of this church . . . was to try to build bridges between authentic evangelicalism and conscientious service in the economic realm.”25 In short, you could be a good Christian AND a successful businessman. With the Bruderthaler, Steinbach gave itself permission to become an economic powerhouse.26

From the early 1900s through the 1930s, Steinbach was visited at least forty times by evangelists, not including the annual visits of Holdeman speakers whose focus was on their own group. All of these were Mennonite, most of them Bruderthaler; most were American.27 By the late 1930s, Steinbach revivalism took on a new form of expression, transplanted from urban America—the street meeting. Up to this point, evangelists had delivered their messages in German. Now, they experimented with English. The first to do so was Steinbach native son John R. Barkman of Henderson, Nebraska, who in April 1938, “preached in English at the street meeting Saturday evening, speaking on the signs of the times.”28 Another innovation was added as a “brass band played evangelical songs.”29 Revivalism provided an entry point for a larger world and revival meetings provided socially approved theatre in a town where worldly forms of entertainment were suppressed.

The Dalzell family of Grandview, Manitoba also held street meetings, beginning in 193830 and continuing through the war years. The Dalzells preached “the living Gospel for a dying world” and featured hymn singing accompanied by guitars and an electric vibra-harp. Their music and their presentation of a Christian family with pretty girls and a redeemed father who had once been the town drunk had a strong appeal for an entertainment-starved Steinbach audience. For the first time in the town’s history, the evangelists were not Mennonite.

The Tabernacle

In 1929, a young man from a farm near Steinbach was converted at one of George P. Schultz’s meetings. This was Ben D. Reimer. As his daughter and biographer Doreen Peters puts it: “He experienced something he had never known: that a person could be converted in one night.” In that night, his struggle with conservative members of his own church, the Kleine Gemeinde, was born. He developed a passion for evangelizing. In April 1946, Reimer held evangelistic meetings in the Kleine Gemeinde church in Steinbach. He was strongly opposed by some elders, especially those from rural villages, and for some years this conflict threatened to tear the church apart.

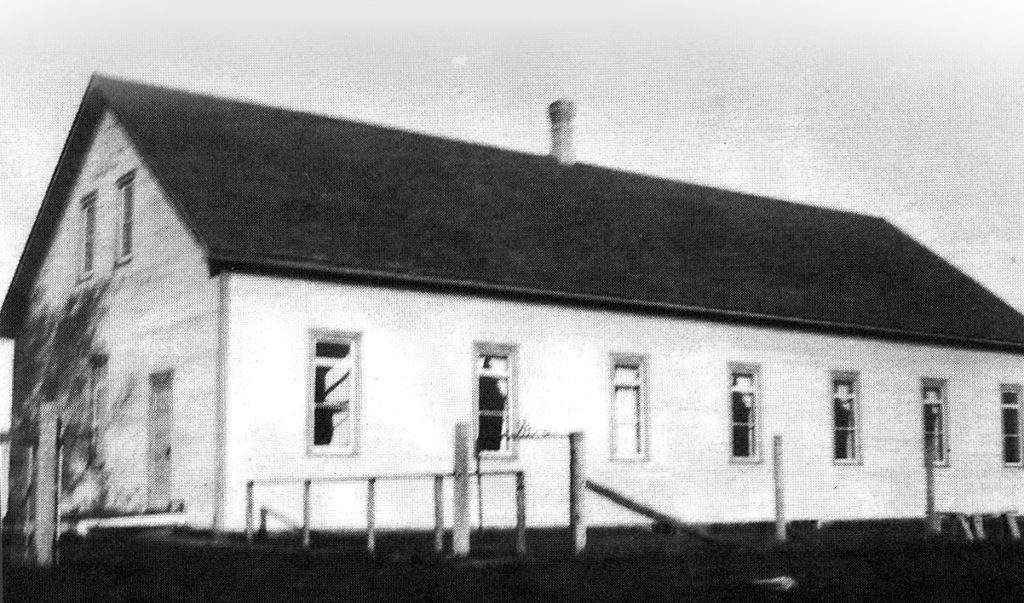

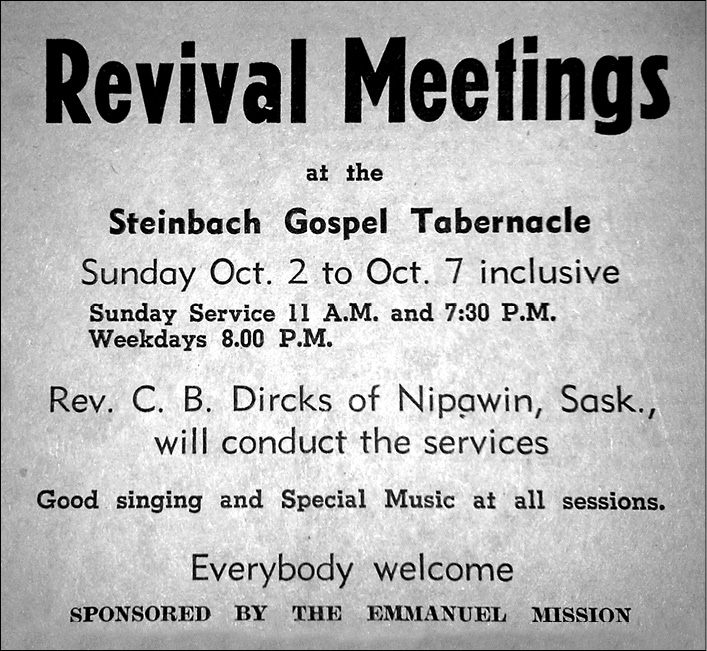

Revivalism was even a factor in the physical appearance of Steinbach. In June 1942, another inter-denominational group built a Quonset-style structure which they called the tabernacle. True to the adage “build it and they will come,” revival meetings were held as soon as the tabernacle was ready. Rev. Peter Tschetter31 spoke in both German and English, followed by the blind evangelist J. J. Esau.32

By the late 1930s, revivalism had inspired an all-Mennonite inter-denominational group to establish the Steinbach Bible School. The school became a kind of incubator for the local revivalist movement. Graduates of the three-year program took courses in personal evangelism and could receive a diploma from the “Evangelical Teachers Training Association” of Chicago.33

In 1946, the Bible School and cooperating churches invited Hyman Appelman, a “Russian-born Jew, formerly successful Chicago lawyer, now internationally known evangelist,”34 to Steinbach. The Carillon News estimated that 8,000 people attended Appelman’s meetings over six evenings at the tabernacle: “This has been one of Steinbach’s greatest evangelistic revivals, 400 people or more decided to turn to God.”35 The town’s population at the time was around two thousand.

Through revivalism, Steinbach developed a missionary consciousness. The EMB had ordained couples as missionaries already in the 1930s, but it was not until the early 1950s that Art and Martini Janz went to Africa under the Congo Inland Mission. Meanwhile the Kleine Gemeinde had formed the Western Gospel Mission in 1946, spearheaded by Ben D. Reimer. Almost immediately, missionaries were sent to Ukrainian communities in rural Saskatchewan. By the early 1950s, the Kleine Gemeinde changed its name to the Evangelical Mennonite Conference (EMC) and formed its own Board of Missions, especially to send Ben and Helen Eidse to the Congo. Mission work became firmly established as a vital part of Steinbach’s religious identity.

The EMC imitated earlier practices of the Bruderthaler, and held their “own” revival meetings annually, featuring American speakers like Marvin Eck and Don Shidler. Shidler, especially, exerted a strong influence, visiting regularly through the 1950s, 60s and 70s. He probably had a greater effect on Steinbach’s religious culture than did big-name evangelists with their one-time visits.36

By the mid-1940s, the target audience for revivalism expanded to include children. In the traditional Mennonite view of redemption, children were members of God’s kingdom, maintaining this status until they either accepted or rejected conversion as young adults. Now the so-called “age of accountability” was lowered to twelve or even ten years old, and an “innere Mission” began, to evangelize even the children of life-long church members.37

In 1946 the Kleine Gemeinde united with other denominations in Steinbach to found Red Rock Lake Bible Camp in the Whiteshell of Manitoba. Many children and adolescents from Steinbach attended. It was hoped that they would be born again and come home with a testimony to share. Also, different churches began to offer summertime Daily Vacation Bible School classes.

Revival preachers had always relied on fear as a motivator for conversion, by emphasizing the “end times” scenario and the risk of eternal punishment in the fires of Hell. Some church people jokingly spoke of “scaring the hell out of people.” But what happens when you scare the hell out of children? Revivalists did not seem to worry about the ethics of their tactics.

Mennonite historian and retired teacher Ernest Braun recalls his experience as a 10-year-old Chortitzer newcomer to Steinbach in 1958, of encountering a Saturday night street meeting: “That the town fathers felt it was necessary to have a public meeting on the street where the people of town would be flagellated, and that would take place the night before we all went to church—that idea was heartbreaking to my little understanding. What was the point if Sunday school and church were not accomplishing their purpose in edifying and supporting our Christian walk?”38

Revivalism affected family dynamics. As a young teenager, poet Patrick Friesen answered the altar call at a revival meeting in the 1950s, only to find that, instead of joy, he felt “hollowed out, defeated.” His conversion had not worked. Leaving the church and seeing his parents sitting in their car, smiling, he felt that he had betrayed them by not getting saved, despite his intentions of pleasing them. On the other hand, he felt that his parents had betrayed him, albeit without malicious intent: “They gave me over to others to do their work with me, to break me down in order to save me.”39

Brunk and Company

In June 1957, George R. Brunk II arrived in Steinbach from Denbigh, Virginia in a semi-trailer with the motto “the whole gospel for the whole world” emblazoned on it. The trailer transported his huge, circus-style tent. Brunk, a Swiss Mennonite who had schooled himself in the art of mass revival, was an imposing and impressive figure, standing six-foot-four and speaking with a deep, powerful voice.

The Steinbach meetings drew thousands, including many children and young people. All the Mennonite evangelical churches in Steinbach took part in the organizing and sponsorship. Ben D. Reimer observed that “warmer fellowship among the different church groups” resulted from these meetings. He added: ‘Scores of lost men and women, boys and girls found forgiveness of sin and peace for their souls, as they repented of their sin, forsook it and surrendered to the Lord. Backsliders were restored. Victories were won over habits that displeased the Lord.”40

It was evangelism on the business model, with statistics carefully kept to measure success. The rural campaigns in Manitoba, which included Winkler and Altona, resulted in 907 responses to invitations to salvation (all recorded on “decision cards”), 1650 dedications, and total offerings in excess of $24,000. Brunk was credited with exposing the “falsehoods” of the kirchliche way, striking “deep into the heart of a formalistic and traditionalistic Mennonite community life.”

In the summer of 1965, another tent evangelist set up stakes in Steinbach. This was Max Solbrekken, the son of immigrant Norwegian parents. Although not as tall as Brunk, Solbrekken established his “he-man” credentials with stories of his pugilistic background and confrontations with knife-wielding thugs and agnostics bent on disrupting his meetings. Solbrekken added a new element for Steinbach audiences—he claimed the power of divine healing of physical and mental illnesses and performed “miracles” on the stage. Stiff-limbed people became mobile, deaf people were made to hear, and drug addicts were cured of their habits.

A Carillon News article stated that “between 1500 and 2000 persons heard God’s servant on closing night.” The headline-writer declared that “Steinbach had never seen anything like it.”41 Subsequent to Solbrekken’s visit, a local Ukrainian-Canadian evangelist formed the Full Gospel Fellowship church (Pentecostal) in Steinbach.

No more tent meetings were held in Steinbach. With increased mobility, residents could easily get to Winnipeg, and large numbers did go to hear the Janz Team in the Winnipeg Auditorium in 1964 and to Billy Graham’s “Centennial Crusade” in the Winnipeg Arena in 1967. The next year, 3,400 people packed the newly built Steinbach arena on the opening night of an eight-day “Crusade for Christ” held by Barry Moore.

By the 1970s, revival meetings were becoming rarer, perhaps because the charismatic movement was growing, and revival-style preaching was integrated into the churches’ Sunday services. Some of the last revival meetings in Steinbach were those conducted by the Sutera twins, Ralph and Lou. The Suteras, from Ohio, were agents of an organization called the Canadian Revival Fellowship.42 Well-groomed and smartly dressed, they had no big tent or tabernacle or arena. Instead they ministered in church buildings, and featured something called a “prayer room,” a separate space from the main worship area, where people were invited—or pressured—to go when they felt themselves to be under conviction.43 The Suteras held meetings at the EMC church in January of 1978. The effects of these meetings were mixed; some people became more dedicated Christians while others actually left the church.

The Fruits of Revivalism

Revivalism was an important factor in the establishment of new church congregations in Steinbach, each responding to some variation of theology or practice that seemed to its members a truer expression of faith than the one they had left. Over the years, hundreds and perhaps thousands of individuals had a conversion experience. Without such conversions, they might have been “lost.” From the standpoint of fundamentalist theology, this fact alone stands as a wonderful outcome. As well, revival meetings gave many people an opportunity to bring their existing commitment “up to date,” without necessarily making a public statement about it.44 For many, making a decision for Christ supported a stable home life, charitable giving,45 and success in making a living.

On the other hand, revivalist methods generated informal resistance, especially from adolescent youth. In the 1970s, a revival preacher urged Steinbach high school students to “bring rock records and filthy books and romance novels and makeup to be destroyed.” One student dutifully trashed her rock records but held some back to sell to “unsaved” classmates. She did not want to suffer a total loss.46

Other young people responded by blaspheming or “spotting” as they tried to relieve the unbearable seriousness of the terrible choice between heaven and hell. Some would imitate the content and rhythm of revival preaching, accompanied by others who would sing or hum “Just As I Am,” in an atmosphere of suppressed hilarity mixed with concealed dread.47 Revivalism presented challenges to faith and intellect and the need to belong. How individuals met such challenges powerfully affected their psychological development.

Revivalism seems to have left municipal politics untouched. Steinbach did not become a theocracy. Many of the mayors and councillors, while they would have called themselves “Christian,” did not identify as fundamentalist or even evangelical, and ran town affairs in a spirit of pragmatism promoting continuous growth. In the larger political picture, however, Steinbach’s current strong adherence to conservativism corresponds closely to the politics of American fundamentalists.

It is possible, even likely, that from its inception Steinbach attracted more revivalist activity than any other small population centre in Canada. But not every trace of traditionalism in Steinbach was erased. The Mennonite Heritage Village, dedicated to telling and honouring the traditionalist story, has become a vital part of the city’s identity. There are megachurches, but not every church is fervently charismatic or fundamentalist.

William James says that the circumstances of human life teach us that we are helpless and dependent. Accordingly, a “religious” response is required, of surrender and renunciation and sacrifice. The traditionalists tried to nurture such a response over the whole adult life-span, the revivalists tried to orchestrate it as a crisis in one’s life. Either way, as a community, Steinbach’s identity was, and continues to be, indelibly “religious.”

- This article is based on a presentation given at the Mennonite Heritage Village, sponsored by the EastMenn Historical Committee. ↩︎

- Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick, “Institutionalizing the Revival: The Culture of Revolutionary Christianity,” October 4, 2012, https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/orthodoxyandheterodoxy/2012/10/04/institutionalizing-the-revival-the-culture-of-revolutionary-christianity/. Accessed March 29, 2018. ↩︎

- George Marsden, quoted in Calvin Redekop, Leaving Anabaptism (Telford, Pennsylvania: Pandora Press, 1998), 174. ↩︎

- William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience (New York: The New American Library, 1958), 184. ↩︎

- G. G. Kornelsen, in the Steinbach Post, May 4, 1938. ↩︎

- Leland Harder, Steinbach and its Churches (Elkhart, Indiana: Mennonite Bible Seminary, 1970), 35-6. ↩︎

- P. J. B. Reimer, ed., The Sesquicentennial Jubilee: Evangelical Mennonite Conference, 1812-1962 (Steinbach: The Evangelical Mennonite Conference, 1962), 23. ↩︎

- Royden Loewen, Family, Church, and Market (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 175. ↩︎

- Steinbach Post, November 9, 1938; A. F. Reimer, Diary, November 7, 1879; Royden Loewen, Blumenort: A Mennonite Community in Transition (Steinbach: Blumenort Mennonite Historical Society, 2nd edition, 1990), 180-183. ↩︎

- In Delbert Plett, Pioneers and Pilgrims (Steinbach: D. F. P. Publications, 1990), 560. ↩︎

- In Genealogy of Jacob M. Barkman (Steinbach: Martens Printing, n. d.), 74. ↩︎

- Clarence Hiebert, The Holdeman People: A Study of the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, 1858-1969, (PhD thesis, 1971), 164; Peter J. B. Reimer, ed., The Sesquicentennial Jubilee: Evangelical Mennonite Conference, 23. ↩︎

- William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, 181. ↩︎

- Leland Harder, Steinbach and its Churches (Elkhart, Indiana: Mennonite Biblical Seminary, 1970), 35-6. ↩︎

- Strangely, on the level of commerce and everyday interaction, Steinbach carried on almost as if nothing had happened. The new religious ideas of the Holdemans were expressed within that group, while the Kleine Gemeinde held to own beliefs. Social interactions, while limited in certain ways (they would not attend each other’s’ funerals or weddings) continued, particularly in civic administration or business. Holdeman Gerhard R. Giesbrecht served as Steinbach’s Schulz, or mayor, exactly at the time of the split, and Johann G. Barkman served as Schulz of Steinbach for many years after that. ↩︎

- Ernie P. Toews, Peter R. Toews 1872-1953 (self-published, 1998), 24. See also Helmut Huebert, Molotschna Historical Atlas (Winnipeg: Springfield Publishers, 2003), 194: “Revival came to the Molotschna in 1884 and 1885, especially in Margenau and Waldheim.” ↩︎

- Steinbach Post, September 23, 1942, and K. J. B. Reimer, Die Post, April 13, 1965; Ernie P. Toews, “The Steinbach Evangelical Mennonite Brethren Church,” unpublished mss. ↩︎

- Mennonitische Rundschau, June 10, 1908. ↩︎

- Royden Loewen, Family, Church, and Market, 242. Loewen is quoting from Schultz’s “Autobiography.” ↩︎

- Leona Rempel, interview, June 11, 2018. ↩︎

- Karen Armstrong, The Battle for God (New York: Ballentine Books, 2000), 145. ↩︎

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Dwight-L-Moody, accessed March 12, 2018. ↩︎

- Frank H. Epp, Mennonites in Canada, 1786-1920 (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada), 237. ↩︎

- Calvin Redekop, Leaving Anabaptism, 191. ↩︎

- P. J. B. Reimer in Leland Harder, Steinbach and its Churches, 48. ↩︎

- Glen Klassen, email, February 19, 2018. ↩︎

- According to newspaper notices and the diary of Rev. Peter D. Friesen. ↩︎

- Barkman was of pioneer stock, a grandson of miller Peter T. Barkman and merchant Klaas R. Reimer. A convert to the Bruderthaler, who by then had re-branded themselves as the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren (EMB), he was one of the founders of Grace Bible Institute in Nebraska, a fundamentalist college attended by many Mennonites, including some from Steinbach. ↩︎

- Steinbach Post, April 13, 1938. ↩︎

- Peter D. Friesen diary, May 28, 1938. ↩︎

- Evidently, a “Prairieleut” or non-communal-living Hutterite. ↩︎

- Steinbach Post, July 1, 1942. ↩︎

- Steinbach Post, October 18, 1939. ↩︎

- Steinbach Post, July 3, 1946. ↩︎

- Peter D. Friesen diary, July 17 and 19, 1946; Carillon News, August 8, 1946. ↩︎

- Reg Toews, interview, June 11, 2018. ↩︎

- Calvin Redekop, Leaving Anabaptism, 167. ↩︎

- Ernie Braun, email, April 4, 2018. ↩︎

- Patrick Friesen, email April 11, 2018. ↩︎

- In Frank H. Epp, ed., Revival Fires in Manitoba (Denbigh, Va.: Brunk Revivals Inc., 1957). ↩︎

- Carillon News, September, 1965. ↩︎

- See Praxis website: https://www.praxisministries.org/crf. (Accessed July 31, 2018.) ↩︎

- Damick, “Institutionalizing the Revival.” ↩︎

- Travis Reimer, email, March 28, 2018. ↩︎

- Steinbach leads Canadian cities in median charitable donations. See: Global News, February 22, 2017, https://globalnews.ca/news/3265299/fewer-canadians-giving-to-charity-but-more-is-being-given/. Accessed August 3, 2018. ↩︎

- Edward Krahn, email, January 25, 2018. ↩︎

- Edward Krahn, email, January 25, 2018. ↩︎