Anadol Forestry Unit

David Rempel Smucker

The forestry service (Forstei in German) was the fruit of a decade of negotiations between Mennonite leaders in Russia and Tsarist officials in light of the introduction of universal military service in the empire. It became law in 1880.1 A head forester, usually a Russian national appointed by the Forestry Division of the Ministry of State Domains, would be responsible for the entire unit or camp. The Mennonite recruits could choose a unit foreman (starshii in Russian) from among their own men, as well as several aides (Gefreiter in German) to the foreman. The Mennonite churches would choose a business manager (Oekonom in German) and a chaplain.2 The duties of the men in these camps centered on improving and protecting the forests, both fruit and forest trees, by planting, thinning, and guarding them. They also distributed saplings to the local Russian population with the hope that those receiving these saplings would continue to expand their own fruit orchards and forest plots.

Gerhard G. Dueck

Gerhard G. Dueck3 was born on 27 May 1891 to Gerhard Dueck and Margaretha Wiens in the Schönfeld settlement.4 At age twenty-two he began his term in the forestry service (Forstei) for about five years (1913–1917) at the Greater Anadol forestry unit about sixty kilometers north of the Sea of Asov in Ukraine. Created in 1881, Greater Anadol was among the first two forestry units. On 3 May 1923, he married Anna Braun and immigrated to Canada in 1924, where he settled near Springstein, just west of Winnipeg, Manitoba, and attended the Springstein Mennonite Church. From 1951 to 1980 he led and/or participated in a series of eleven reunions of Mennonite men (and often their wives), who did alternative service in Russia in the forestry service and/or the medical orderly service before and/or during the First World War. He died on 29 January 1985.

Two translated and annotated accounts written by Dueck follow: an account published5 in translation6 in 1966, Onsi Tjedils, and a shorter, unpublished account, translated by his daughter from his handwritten papers.7 Although we find some repetition, the two accounts each provide materials not found in the other.

Onsi Tjedils

At the beginning of March 1913, I made preparations to begin my forestry service at the Anadol forestry unit. A large box was procured and filled with provisions such as ham, sausage, butter, and a large glass container of marmalade (Warenje).8 Underwear was packed. Outerwear was provided at the forestry unit. That consisted of a grey uniform, shirt and pants for work days, a grey suit with shiny white buttons and a green collar for Sundays. In summer we wore white clothes for work with a peaked visor cap; instead of shoes we received money for boots. That is how we were provided for: from home by our dear parents and at the forestry unit by the mother colony, that is, by all the Mennonites through a specifically levied assessment per capita.

After arriving at the Wolnowacha9 station, I hired a carriage for the 8 verst10 trip to the barracks. As we turned into the driveway and by the time I dismounted, my baggage had disappeared into the barracks. “Very eager service,” was my thought. My cousin met me and took me to room #3. That had already been arranged beforehand. A while later he asked, “Where are your things?” “I don’t know,” I answered. “I only know someone hollered ‘two here’ as I came on the yard.” “Well,” he said, “then they will be in #2.” The explanation is that they thought that if they got the belongings, they would get the man. My cousin went searching and came back shortly without my things but with about 10 fellows. Greetings followed: “What’s your name?” I answered. “Is Dave Friesen your relative?” “Yes,” was my answer. “You’re not lying.” After I had good-naturedly answered everyone, my belongings were returned. (David Friesen11 was my cousin and was the foreman at that time. He died in the North.)

I got my belongings, but the outer bindings were in pieces and the marmalade did not survive the stormy reception. The bindings were returned in pieces with the explanation. “We are honorable people. We always return everything, even in pieces.” You can imagine what the contents of the box looked like. In the meantime other newcomers arrived. We all received a large sack and were instructed to go to a big stack of straw. That is where we would find the colony feathers to fill our sacks. In the barracks we were to sew up the open end. One of the elders was there with a container of water into which we had to dip our needles periodically to prevent them from getting too hot and setting the straw on fire. They would not want to be responsible for that.

The bed consisted of a framework of boards with holes on each side through which cords or ropes were pulled; it served in place of a bedspring. The bed frame had four legs; above was the aforementioned large bag of straw that we sewed up, a pillow, a bedspread and a blanket. And did we ever sleep soundly! The bed frame was decoratively painted.

On the first day the rules were read to us before we went to bed, how we would need to behave at the outset of our service. Through D. Friesen’s efforts, I managed to get into instruction in the tree nursery and in the garden. After we had received all our equipment, we went to the Teritj.12 Since the forest was over 1,000 Desjatinenen13 large, we had another purpose: to construct a small barracks about 5 versts14 further [from the workplace], so that we would not have to return the entire distance to the workplace everyday.15

On the first day at work we hauled underbrush out of the forest to the road. The second-year men then bundled it. When they realized that we would be unable to reach the prescribed quantity in the prescribed time frame, they demanded that we increase our efforts another notch.16 We could not increase our efforts, so we just had to work a little longer to reach our quota. Luckily, it was Saturday when we regularly only worked until noon. In time we got used to the work.

When work began in the garden and in the nursery, 12–15 men were transported to primitive summer houses. The more interesting activities there were pruning trees, grafting, picking fruit, etc. In spring and fall many fruit trees and forest trees were widely distributed. Starting in my second year, it was my job to bring the packaged trees to the station. Peter Isaak,17 a third-year man, introduced me to this work. We made up to 20 trips per day.

We also had a wonderful, large fruit garden. Fruit trees and vines of various kinds lined the avenue with their different kinds of fruit. I have a picture of five guys standing in front of a gate covered in vines. In the summer we were awakened by the singing of the nightingales.

We got a lot of visits from our fellow servicemen in the forest when the fruit was ripe. I can still visualize Jacob Schroeder18 (died several years ago in an invalid home) coming around the corner with his motorcycle dragging his long legs to come to a stop. He seldom used his brakes. Yes, where are all our dear friends? Nick Rempel,19 my true friend—we spent the entire 5 years in service together. He perished in exile. His family is in Canada. Hans Dueck20 belonged to our work detail. W. Bartel, our head gardener, is said to have perished in Koltschak’s army,21 Peter Mandler,22 Andreas Vogt,23 the foreman David Friesen—I could go on and on naming names of those who were dear to me.

We too had visits from preachers. In the summer of 1914 Rev. Bartel, the father of the head gardener, and the teacher Rev. Benjamin Unruh24 came for a visit. On the same day we got the news of Russia’s declaration of war on Germany. Benjamin Unruh then declared, “Now we’ll get a new Russia.” It did not take long before a call went out for volunteers for the medical service. Many registered, including Nick Rempel and I; we were asked to stay because we knew the work. We stayed until everything fell apart.

First war, then the overthrow of the Tsar, Kerensky, and finally the Bolsheviks. For 5 years I served the fatherland as a non-combatant. Because the war was against Germany, we were forbidden to speak in German. This directive was difficult to adhere to because we had not used the Russian language in forestry service. (In Canada it was not difficult to relinquish the German language.) When someone spoke Russian in forestry service, he was smeared with shoe polish. We were afraid that he would lose the hair or the skin on his chest.25 Such a patient was cured for life. During peacetime we often received leave. This was forbidden during wartime, but then we got more visitors at the forestry unit—parents, relatives, women and brides came for visits.

Our business manager or Papa, as he was called, was Preacher Abram Klassen.26 He had ably proclaimed the word of God to us. That had positive consequences. There were opportunities for Bible studies, prayer meetings, and music sessions. A well-stocked library was at anyone’s disposal. There was opportunity for growth and activities to enjoy during the idle hours. One of the more educated men was given time off from work, in order to do some active teaching. There were some who were interested in furthering their education. During my time the teacher was Heinrich Enns,27 later from Steinbach. He was editor of the Post. He died several years ago. He was a student in the vocational high school in Berdiansk.

Breaking the rules, despite repeated warnings, was severely punished, and in some cases, with lashes. This was so-called Schinelliborscht.28 And even then, sad to say, there were things that happened that had a life-long effect.

In the fall of 1917 our horse barn burned down. Several days later we were overrun. I was on leave at home at that time and did not return to service. That was the end of this chapter. What followed was a difficult time. I am thankful for God’s grace and guidance.

Because I wrote at the beginning about bringing some food to the forestry unit, some of you may be led to believe that there was not enough food to eat at the forestry unit. That is not true. There was good nourishing food. The cooks and the bakers did their best to keep the unit satisfied. The provisions from home were for between meals. The dear mothers were always so worried that their sons were not well cared for.

“Stories … By My Parents”

In 1912 I was conscripted. To fulfill my obligation to the state, I had to work in the forestry department. So in March of 1913 I left by train for the Forstei, Greater Anadol. When I arrived at the station, I hired a carriage/wagon to go the camp where I would work. Before the vehicle could come to a complete stop, the guys had already grabbed all my boxes and bags and thrown them on the camp wagon; we went for a rather boisterous ride. Later when I unpacked everything, I found to my horror and chagrin that several of the jars of jam and preserves my dear mother had so lovingly packed among my clothes were broken. You can imagine how my clothes looked. Needless to say, the next few days I had to spend my spare time washing and cleaning my clothes, towels, etc. That was not my idea of fun.

My first day of work was Saturday. We worked hard all morning, and were hot and sweaty when we arrived back at camp. Lucky for us, it was Saturday, when we only worked until noon.

There were different areas of work. Since my cousin, David Friesen,29 was a leader of a group of 12–15 men working in the orchards, I was assigned to this area. I enjoyed this very much. I learned a great deal about transplanting, pruning, grafting, and thinning so that fruit trees would thrive and produce more and better fruit. I learned as much as possible and hoped to utilize this knowledge to improve our orchard at home. During Spring and Fall many shrubs and trees were sent to different parts of the country. I was designated to take these to the train station by wagons and horses. I enjoyed this job very much; in fact, I enjoyed all my time at the Forstei, where I worked for almost five years.

At first we had regular leaves, could go home or to relatives; our families were also able to come and visit on occasion. Then the war broke out and our privileges were cut off—no more visiting. Until then we had mainly spoken Low German, even if our administrator was Russian. That came to a sudden halt. Most of the young men had only attended the German village schools and their skills in speaking Russian were limited. If they were caught speaking German, the resulting punishments were often unpleasant—even flogging.30 I was fortunate; I had learned Russian in the high school [Zentralschule]. And at home we always had Russian workers, so that I was quite fluent in the language.

A bit more of life at the forestry camp. It was a place of approximately 3,000 acres, mostly forest. Poplars, ash, oak, as well as other trees and shrubs were among those grown there. The older trees were chopped or sawed off and, as I already mentioned, taken to the train station and shipped to other parts of the country.

Our main camp had five bunkhouses with 20 men in each one. There was a special house for the leader/organizer and another for the maintenance person. This house was also the home of our minister and his family. The preacher held Sunday morning services. His services were certainly needed. We also had visiting clergy from our home villages speak to us. I remember Preacher Abram Klassen31 encouraging us to walk in the ways of the Lord; those messages really spoke to my heart. We also met in small Bible study groups. There was quite an extensive library, very good books. I enjoyed reading, so read many a book. Oh, and then there was sports, something I was very much involved in.

Minister Benjamin Unruh32 came to speak to us the day war was declared between Russia and Germany. He said: “After today Russia will never be the same again, it will be entirely different.” His prophecy certainly was fulfilled, and we experienced that. All forestry camps were eventually closed and we were sent home.

- Jacob Suderman, “The Origin of Mennonite State Service in Russia, 1870–1880,” Mennonite Quarterly Review XVII (1943): 23-46, is the earliest account in English. Lawrence Klippenstein, “Launching the Russian Mennonite Forestry Service,” Peace and War: Mennonite Conscientious Objectors in Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union Before World War II, and Other COs in Eastern Europe (Winnipeg: Mennonite Heritage Archives, 2016), 69-83. The first two sites, Greater Anadol and Asov, were built and occupied in 1881. ↩︎

- Klippenstein, Peace and War, 74-75. “Sometimes one person served as both chaplain and business manager.” ↩︎

- Der Bote 62:8 (Feb. 20, 1985): 7. He and his wife celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary in 1973: Der Bote 50:21 (May 22, 1973): 5. ↩︎

- The Schönfeld settlement, Dueck’s birth location given in the Der Bote obituary, was an area comprised primarily of private estates, approximately fifty kilometers north of Molotschna Colony. See Rudy P. Friesen, Building on the Past: Mennonite Architecture, Landscape and Settlements in Russia/Ukraine (Winnipeg: Raduga Publications, 2004), 455-470. ↩︎

- David P. Heidebrecht, Gerhard J. Peters, Waldemar Günther, eds. Onsi Tjedils: Ersatzdienst der Mennoniten in Russland unter den Romanows (Clearbrook, British Columbia: self-published, 1966), 40-44. ↩︎

- Our Guys: Mennonite Alternative Service in Russia under the [sic] Romanows, trans., Peter H. Friesen (Beausejour, MB: Bethania Mennonite Personal Care Home,ca. 1995), 34-36. This English translation of Onsi Tjedils served as the basis for this translated account by Gerhard G. Dueck. The author has done editing, such as translating lines omitted in the English translation and adding information in notes. The author has also made some copy editing changes, such as changing paragraphing and correcting grammar, spelling, and punctuation. Lawrence Klippenstein, Winnipeg, gave helpful advice concerning Russian, German, and Low German. ↩︎

- Elizabeth (Dueck) Peters, “Stories written by my Parents and Others,” unpublished typescript, 3-4. What is printed here is an excerpt of the typescript, which is fifteen pages in length. Mrs. Peters, daughter of G. G. Dueck, lives (2018) in Gnadental, Manitoba. ↩︎

- Russian word for marmalade. ↩︎

- Probably “Volnovakha,” as in W. Schroeder and H. Huebert, Mennonite Historical Atlas: Second Edition (Winnipeg: Springfield Publishers, 1996), 63. ↩︎

- Distance measure: 8 Versts equals ca. 8.8 kilometersor 5.28 miles. ↩︎

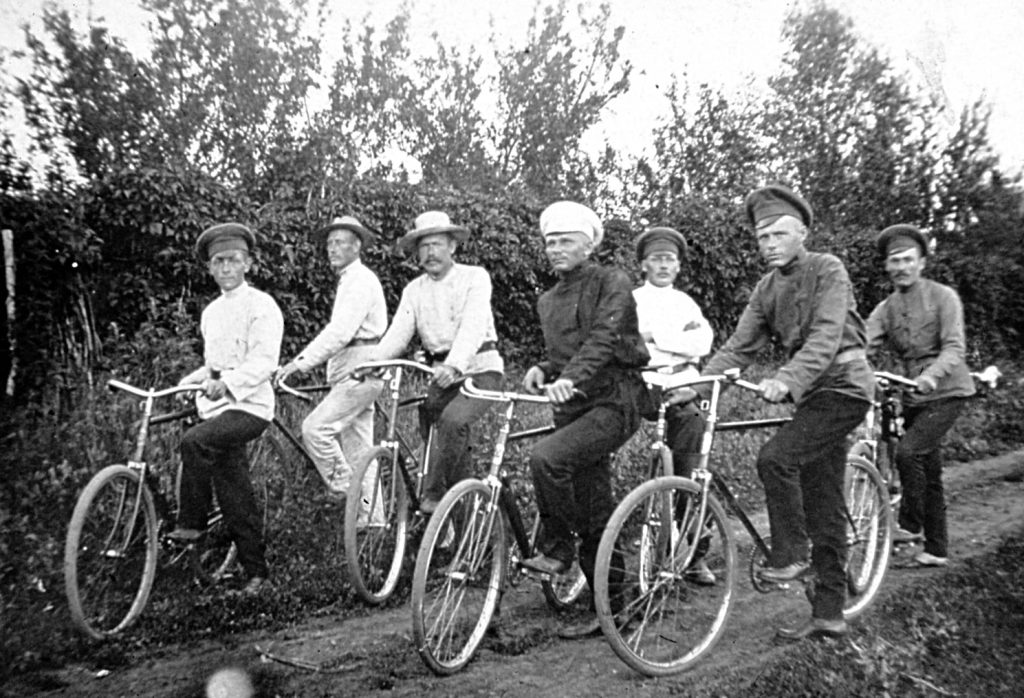

- Presumably David G. Friesen (6.10 in 1913 Anadol photograph). See Helen Koop Johnson, A Tapestry of Ancestral Footprints (Waterhouse, SK: self-published, 1995), 216-217, for a sketch of his life. All numerals following or associated with individual names refer to the author’s unpublished studies. ↩︎

- Teritj is a Russian word possibly referring to the place where protective cream was rubbed on the body to deter insects. ↩︎

- Land measure: approximately1,000 dessiatines = ca. 1,092 hectares or 2,700 acres. ↩︎

- Distance measure: ca. 5 versts = approximately 5.3 kilometers or 3.3 miles. ↩︎

- Our Guys, 35, omitted the translation of all the text between “After we had received . . .” and “. . . workplace everyday.” ↩︎

- Mau oapgeschroawi is probably Low German for increase/turn up/ratchet up something. ↩︎

- 6.15 in 1913 Anadol photograph. ↩︎

- 5.9 in 1913 Anadol photograph. Present at 1951 reunion in Manitoba (2.19). ↩︎

- 3.1 in 1913 Anadol photograph. ↩︎

- Possibly at 1951 reunion in Manitoba (17). ↩︎

- Alexander V. Kolchak (1874-1920) was a Tsarist naval admiral, who sought to bring together the pro-Tsarist armed forces after the revolution. He was later based in Omsk, Siberia, and received Allied support. His efforts failed and the Bolsheviks executed him. ↩︎

- 7.4 in 1913 Anadol photograph. Der Bote 57:2 (Jan. 9, 1980):7, an obituary of his wife, Katherine (Warkentin) Mandtler, states that Peter (d. 1970, St. Catherines, Ontario) became a Mennonite Brethren pastor. ↩︎

- 9.7 in 1913 Anadol photograph. Present at 1951 reunion in Manitoba (2.36). ↩︎

- Presumably Benjamin H. Unruh (1881-1959). See Harry Loewen, ed., Shepherds, Servants, Prophets: Leadership Among Russian Mennonites, 1880-1960 (Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press, 2003), 401-426. ↩︎

- This is a speculative translation of the Low German phrase, “. . . daut am de Brost aufschali kunn . . . ,” which refers to some type of hazing punishment. ↩︎

- Our Guys, 36, omits the name of Preacher Abram Klassen (4.9, 1913). 4.9 in 1913 Anadol photograph. Klassen is pictured with his wife in Walter Quiring and Helen Bartel, Als Ihr Zeit Erfüllt War: 150 Jahre Bewährung in Russland (Saskatoon, SK: self-published, 1963), 172:5. ↩︎

- Present at 1951 reunion in Manitoba (10). ↩︎

- “Schinelliborscht” refers to a type of physical punishment, as described in detail by Franz P. Thiessen in Onsi Tjedils (60) and Our Guys (48). The “Schinell” was a forestry coat thrown over the head of the person to be punished, so that he could not see the identities of his fellow forestry volunteers. Two belts wrapped together served as the lashes on a clothed rear of a man. The use of the word Borscht (a Ukrainian soup loved by Mennonites), in this context, is presently unknown. ↩︎

- See note 11. ↩︎

- See note 28. ↩︎

- See note 26. ↩︎

- See note 24. ↩︎