Family Myths and Legends

Glenn H. Penner

Mennonite family legends, new and old, are too numerous to count. Most traditional Mennonite family names have at least one myth regarding their origin or how these surnames found their way into the Mennonite community. Many of these are so outrageous that they can be immediately discarded; although family members often tenaciously cling to these myths claiming that they cannot be wrong. Some appear to have started out as being based in fact and then have been corrupted over generations.

Mennonite family legends tend to follow one or more of a group of themes: 1) Origins of families and family names; 2) Very early family members (possible progenitors); 3) Jewish, Roma, and other origins; and/or 4) Immigration and other exploits.

How do these legends start? Some start as true stories which change (through exaggeration or faulty memory) with each telling and, after a few generations, become almost unrecognizable. Some are essentially invented or seriously exaggerated with the purpose of entertaining or emphasizing the importance of the family. Red hair or an unusually dark complexion running in a family must indicate that an ancestor had an affair with a non-Mennonite (as if Mennonites could not have red hair) or had Roma ancestry.

These days we have access to resources which can help us look into some of these legends. For instance, scans of many original church registers and census lists are now available online.1 Several different types of DNA testing can be used to investigate the ancestry of the descendants of those mentioned in these legends.2 With these tools, we can assess the claims made and attempt to distinguish fact from myth.

Family Legends

The oldest known set of family legends was written around 1785 by Ältester (Elder) Benjamin Wedel (1754–1791) of the Przechowka congregation in West Prussia (later the Alexanderwohl congregation in Russia and Kansas). In the process of starting a church register, Wedel attempted to trace all of the existing families back as far as possible.3 In most cases the information he provided on the earliest known members was based on local folklore. The best-known example was the origin of the Mennonite Ratzlaff family. The first Mennonite Ratzlaff was supposed to have been a Swedish soldier who, upon hearing a sermon (by one of the Mennonite preachers), stuck his sword into a hedge post and was later baptized as a Mennonite, joining the Przechowka congregation and marrying the daughter of Ältester Voth. The timing is about right for such a person to have been in one of the Swedish wars, but Ratzlaff is hardly a Swedish name. If there is any truth to this story the first Mennonite Ratzlaff may have been a soldier of eastern European origin who fought in one of the Swedish wars.

Another early recorded Mennonite family legend comes through the 1815 court proceedings of David von Riesen (Friesen) of Elbing in West Prussia.4 Von Riesen joined the Prussian army during the Napoleonic wars. As a result, he was excommunicated by the Elbing/Ellerwald Mennonite church. After the Napoleonic wars he attempted to rejoin the church through litigation. Von Riesen claimed that, according to family legend, his earliest van Riesen ancestor arrived in Poland (later West Prussia) as a soldier with the army of Carl Gustav during the Swedish War (1655–1660). This is simply not true. First, there were already Mennonite van Riesens in the area before this war. Secondly, van Riesen is obviously a Dutch name and more likely originated from the city of Rijssen in Overijssel. Thirdly, Y-DNA evidence, at this point in time, shows that there is only one Mennonite Friesen/von Riesen/van Riesen family with no evidence of a second Swedish family.

The Legend of Michael Loewen

There is also the legend of General Michael Loewen. This legend can be found in two documents written by Heinrich H. Neufeld that I have translated and reproduced: an article in the Mennonitische Rundschau and a Geschlechtsregister (genealogy) of Michael Loewen. Both documents were copied and annotated by an unknown person with the initials JFF. JFF’s comments are in the parenthesis. In the Mennonitische Rundschau, the following was printed:

“Grandfather Michael Loewen was born in 1606. Married to Sarah Eckert in 1630—just when the Rottenkriege5 was occurring in Germany (meaning the Thirty Years’ War from 1618 to 1648, between Protestants and Catholics), the Emperor sent General Michael Loewen to put an end to the war. His image is carved as a hero in stone and seen in Germany at the gate of the arch, where the emperor makes his entrance. Here he was married and baptized by Georg Hansen as a Mennonite. They lived in Marienwerder. He became 104 years old. In 1633 a son, Karl Loewen, was born; in 1637 a son Nicolaus was born and died in 1640. In 1656 Karl Loewen married Elisabeth Steingardt. They had one child Karl and the mother died. He married again, to her sister Maria Steingardt in 1659. Their children were two sons, Abraham and Jacob, and one daughter. Again, the mother died. In 1683 he married the third sister Martha, the youngest. Their parents were the Abraham Steingardts who also lived in Marienwerder.”6

The “Geschlechtsregister of Michael Loewen” provides more genealogical information about the family that can be tested against other records. I have highlighted some important information for my argument in the square brackets.

“In 1684 their son was born (who was certainly called Michael) and a daughter, Margaretha, in 1688. Grandfather Michael married Justina Hildebrandt in 1710. In 1711 a son named Michael was born. After that there were three sons and two daughters, all died [young]. Grandfather died in 1743 and grandmother died in 1752.

“In 1738 our grandfather Michael Loewen (III) married Katharina Hildebrandt. Son Julius born 1740, son Michael 1743, son Diedrich born 1746, daughter Katharina born 1748 and daughter Margaretha born 1751. Grandmother died in 1768 and grandfather in 1761.

“In the year 1768 grandfather Michael Loewen (IV) married Justina Schellenberg. The children were: Bernhard 1770, Paul 1771, Michael 1773, Jacob 1775, Diedrich 1779, Katharina 1781, Maria 1784, Elisabeth 1787, and Margaretha 1790, who was my grandmother. [This is actually his great-grandmother].

“In the year 1809 this great grandmother married our great grandfather Peter Martens. The children were Peter 1810, Margaretha 1811, and in 1814 my grandmother, named Helena, was born. My great grandmother lived to be 57 years old and great grandfather lived to 87 years and 9 months. They moved from Prussia to Russia by horse and took up residence in Grossweide, where they both died.

“In 1835 my grandmother Helena (nee Martens) married our grandfather Heinrich Ewert and 12 children were born. They moved from Grossweide to Sparrau where they both died.”7

This legend is a mixture of fantasy and factual information. First, during the time of the Thirty Years’ War, generals and other military leaders were taken from various parts of the European nobility or aristocracy. There is no indication that Michael Loewen was part of this group. The Thirty Years’ War is well-documented and there is no record of a leading general named Loewen. The only known European emperor during this time was the Holy Roman Emperor, who was the head of the Catholic coalition in the war. Prussia was only a Duchy and Poland had little involvement in the conflict. This means that Loewen must have originally been Catholic and not of Mennonite descent. However, the idea that he was Catholic is inconsistent with DNA analysis of twenty-three Loewen men, of which four are known to be descended from Michael Loewen (IV) and nineteen who are known not to be descended from this family. The Y-DNA results indicate that the descendants of Michael Loewen belong to the same Loewen family as the rest of the Mennonite Loewens, not a separate Catholic family.8 There does not appear to be any record of a memorial to a General Loewen at any city gate (although such a memorial may have disappeared over time).

The legend also claims that Loewen was baptized by Georg Hansen. Georg Hansen became the Ältester of the Danzig Flemish Mennonite church in 1690.9 Since there was a hard rule that only a Mennonite Ältester could perform baptism Loewen had to have been over eighty-four years old at the time of his baptism. It is claimed that he lived to be 104 years old. At that time such an age would have been a national record, if not a world record, given that those who survived childhood rarely lived past the age of seventy. Aside from this General Loewen myth, I know of no other record of a Michael Loewen who lived during this time period. Although the name Michael does appear in the early Loewen family, the name Karl does not. Considering how strongly early Mennonites stuck to traditional naming patterns it’s hard to believe that two successive Karl Loewens existed without having any descendants with the same first name. What is even more difficult to believe is that Karl Loewen married three sisters over a period of twenty-seven years. I have yet to find any documented evidence that anyone named Karl or Carl Loewen even existed during this time period.

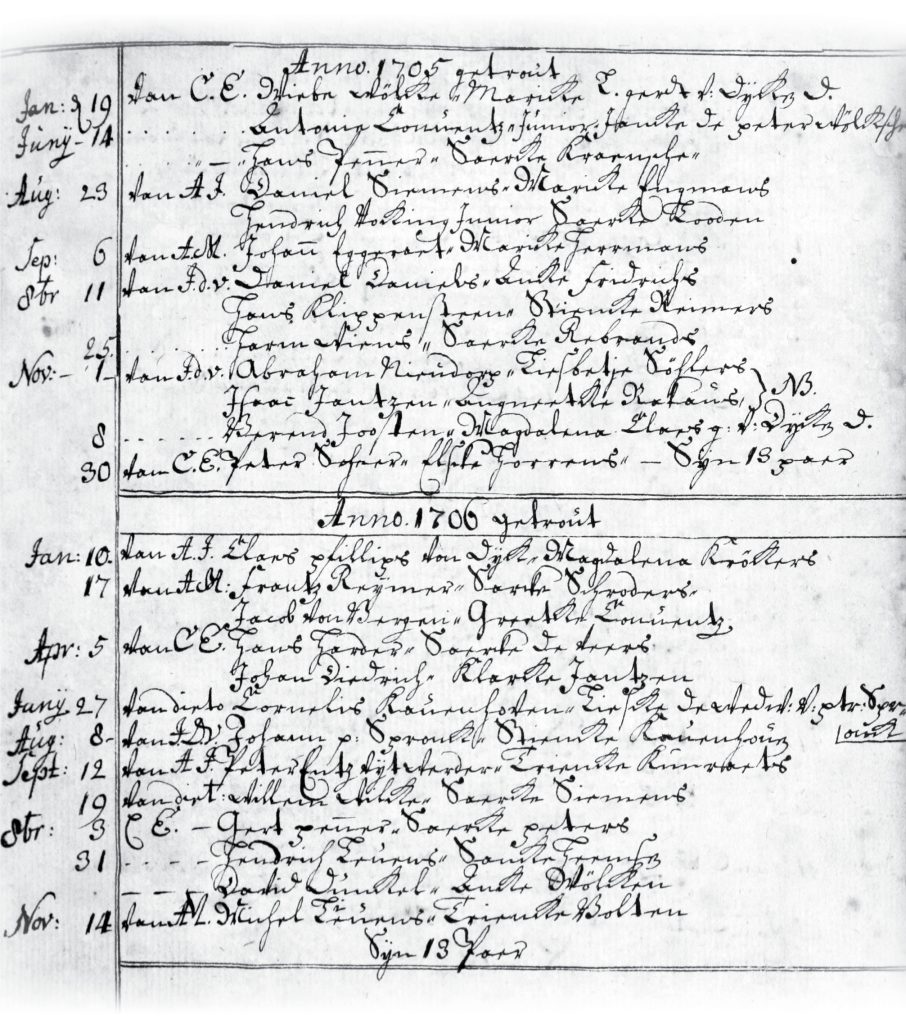

Once passed the first three generations in this family legend things become more believable, although all the dates which can be compared with original records are wrong. Unfortunately, the many discrepancies between the last three generations in the Loewen document and the original church and immigration documents are too numerous to work through here. I will concentrate on the second and third Michael Loewens. The earliest mention of a Michael Loewen is the marriage of Michel Leuens and Trinke (Katharina) Boldt in 1706 in Danzig. This marriage is found in the marriage register of the Flemish Mennonite church of Danzig.10 Both the date and the wife’s name do not match those for Michael Loewen (II). The next occurrence of the name is found in the Catholic burial register for Tiegenhagen (West Prussia, now Poland).11 Mennonites were rarely allowed to have their own cemeteries and were usually required to bury their dead in nearby Lutheran or Catholic cemeteries and pay the required fee. The Tiegenhagen Catholic records mention Mennonites going back to 1721. There are no Michael Loewens until the burial of the wife of a Michael Loewen on 1 December 1742. Michael Loewen was buried on 10 December 1746. These dates do not match those for Michael Loewen (II) and his wife but they are within a decade.

The next mention of a Michael Loewen is the death of Elisabeth, wife of Michael Loewen of Tiegenhof, on 31 December 1758 at the age of forty-two years. If this refers to Michael Loewen (III) the date is out by ten years and the name is wrong. There is also a Catharina Loewen who died on 20 January 1770 in Tiegenhof at the age of fifty. However, she could have belonged to any one of the several Loewen families who lived in the Tiegenhof region at that time. I have been unable to find the death of Michael Loewen (III) in the Tiegenhagen Catholic records. Mennonite records for this region were not started until 1782.12 The family of Michael Loewen (IV), who later immigrated to Russia, is found in these records. The original General Michael Loewen document must have been written long after the immigration of Michael (IV) to Russia in 1804 and appears to be based on a mixture of memory and imagination. The birth date of Heinrich H. Neufeld’s own grandmother and her siblings and the marriage date of her parents are all wrong.13

The most frustrating aspect of this is that the original document owned by Heinrich H. Neufeld (1876–1947) has disappeared. Only copies, which themselves have inserted information, or where dates are re-jigged, are available.

The Noble Blatz Family

Another family legend concerns the nobility of the Blatz family. Members of this family did not join the Mennonite community until after their immigration to Russia and most of their descendants are found in Manitoba. The following information was posted on the message board of the Ancestry website: “My information on Michael Blatz is that he is from nobility in Germany. He was the son of the King’s family. He lived in a castle where the Rhine and Necker Rivers join, not far from Mannheim and Heidelberg, Germany. He was a Doctor of Philosophy and his 2 sons were well educated in Heidelberg. In 1812, during the Napoleon[ic] wars, Michael, his 2 sons, Daniel and Andrew and his wife, fled to Russia. They loaded up all they could carry into two handcarts and walked to the Molochei [sic] area in Russia. His sons Daniel and Andrew taught school. The family was of the Catholic faith, but Daniel was baptized in the Mennonite faith in Russia.”14

The following description from the GRANDMA database version 5.06 supports this interpretation: “Michael Blatz lived in a castle in Germany, and was a member of the nobility. The castle was destroyed in 1712, after which time he moved to Russia. The castle was located at the junction of the Neckar and Rhine Rivers. They moved to Russia with a two-wheel cart in 1804: Michael, his wife, and his two sons (Blatz, D.G. p. 8; K. Stumpp, p. 395). In the 1811 Prischib Colony Census he is listed at Alt-Nassau #44, where his surname is given as Platz (K. Stumpp, p. 885).”15

According to research done by Cornelia Carstens of Germany,16 using Catholic church records of Obernburg near Heidelberg, the only confirmed statements made in these legends is that the family lived in the Heidelberg region before emigrating and that the family consisted of Michael, wife Elisabeth, and sons Daniel and Andreas. Her research shows that Michael Platz was born in Obernburg on 22 January 1756, the son of baker Johann Thomas Platz and Maria Margaretha Guttner. Johann Thomas himself was the son of a baker. Michael married Elisabeth Metzler on 19 July 1785. A son, Daniel, was born on 1 June 1788 and son Andreas was born on 11 December 1795. At that time his father was described as a fisherman (piscatoris in Latin). Exactly when the Platz family moved from Prussia to Russia is unknown. By 1811 they were living in the Prischib colony in the village of Alt-Nassau in Russia.17 Daniel Platz/Blatz transferred to the Mennonites sometime between 1820 and 182218 after marrying Maria Klassen (in 1816 or 1817).

Joseph Nowitzky— the “jewish Mennonite”

The legend of Joseph Nowitzky, the “Jewish Mennonite,” illustrates another type of family myth. The following is a story written by Heinrich A. Dyck (1906–1985): “A Heinrich Dyck was born in Prussia in 1754. When his parents emigrated to Russia he went along. It happened that Heinrich Dyck married and settled down to make a home in that so called Russia. At that time there was a man there by the name of Joseph Nowitzki, who was a businessman. He sold cloth and whatever else was involved with this. Since his sales territory stretched over a wide area he looked for places where he could stay for the night. He found such a place by Heinrich Dyck. From here he went from place to place to bargain, as it is said today. The reason he stayed for night in such places was because it would take too much time to go home every night. It would take too much time and he would not sell as much.

“One day we saw this Joseph Nowitzki come again—and what did we see? He had a child with him—this had not happened before. These people took both of them in, in a friendly manner and welcomed them since they were very hospitable people. They could stay overnight and eat with them. He was also asked why he had the child with him, since it is so cumbersome to have a child along all the time. Then he gave them the reason for this: ‘Look, dear people, my wife has died and I cannot leave my daughter (her name was Maria) alone. That is the reason.’

“The next morning, he asked the Heinrich Dycks if it would be possible to leave the daughter with them while he was making his usual sales trips in the area. When finished he would come and take his daughter home again. (The distance to his home the writer of this does not know). However, while on his business travels the thought struck him—would it be possible to leave Maria with the Dycks permanently? When he had finished his rounds he came back to the Dycks. The next morning he asked the Dycks whether this, leaving Maria with them, would be possible. This was discussed and was accomplished. He, namely Joseph (as we will call him from now on), then drove off in a joyful mood, knowing that his child was in a good place. He came back like before, but this situation, his daughter being here, resulted in a very close bond to this place. However, one other thing has to be mentioned. These Heinrich Dycks insisted that she had to come along to church. This was done. Maria always went along, listened to the sermons, and was happy to do this. Even though she was a Jew and did not understand everything. However, with time she understood more and more.

“Maria matured and became older and she reached the age where she had to go to school. She was a diligent student and thus the teachers and the people were satisfied with her. Maria did not stop with her school years. Oh no! She grew up to be a fine young lady. When she reached the age where it was time to be part of the church membership procedure, she decided to take this step with the help of the Dycks. Joseph, Maria’s father, came again and again to visit Maria. When the membership classes were completed Maria asked to be baptised. When father Joseph came again after Maria was baptised, father Heinrich Dyck said to Maria she should come to him. She was obedient and came. Then father Dyck said to Maria that she should tell her father what she had done. Maria did as father Dyck had asked her and told her father Joseph what she had done, that she had been baptised. Then her father Joseph was displeased with this, spat in his child’s face, and said, ‘From now on you are no longer my daughter!’ He drove away and never came back again. One can imagine how Maria felt about this!

“Maria was not the only child in the family. Oh, no! These Heinrich Dycks had their own children. (The writer does not know how many.) However, there was a Peter among them. When Maria Nowitzki came to the Dycks, Peter felt sorry for Maria and had sympathy for her. Who would not have had sympathy for her? When the time came, that they were of the age for each of them to choose whom they wanted as a partner for life, Peter chose Maria. He took her as his wife. (The writer does not know the date and year when this happened. He hopes to find it.)

“The dear God blessed them with 6 children—Peter, Jacob, Heinrich, Johann, Helena, and Katharina. After Maria Nowitzki died, Peter Dyck looked for another wife and found Maria Regier. From this marriage another 2 children were born—Barbara and Abraham.”19

One can make several observations and conclusions about this version of the Nowitzky legend. First, the early Khortitsa colony families are well documented by the census lists of 1795, 1801, 1807, 1811 and 1816.20 None of these lists show a Heinrich Dyck who fits the description above. More importantly, none of these lists show that Joseph Nowitzky even had a daughter Maria. Also, Joseph Nowitzky’s wife, Helena Boschmann, did not die until 1858, long after the time period of the story above. In fact, Khortitsa colony records show that Joseph Nowitzky was not a travelling salesman of any kind: he started off as a farmer. In 1801 he owned two horses, ten cattle and a wagon. In 1805, he gave up his farm and moved to the Molotschna colony, where he was a miller.21 By 1811 he was back in the Khortitsa colony and living in the village of Neuenburg where he owned six horses, six cattle, a wagon and a plow. Finally, autosomal DNA results for descendants of Nowitzky’s daughter Justina are consistent with Joseph Nowitzky being an Ashkenazi Jew. However, DNA results for descendants of alleged daughter Maria show no Jewish ancestry.

What is the connection between the Dycks and the Nowitzkys? Helena Boschmann, the wife of Nowitzky, was the stepdaughter of Peter Dyck of Neuendorf. However, there appears to be no known connection between this Peter Dyck and the Dyck family claiming to descent from Maria Nowitzky.22

Another version of this story was recorded by Johann Epp: “Justina von Liechtenstein, daughter of the Baron von Liechtenstein, married a Jewish pharmacist Nowitzky. Because of this they were rejected by her parents. The young Family Nowitzky was in a bad way. They came to Poland, then to Russia. There they met the Mennonites and found help with them. They accepted their belief. Her daughter married Low German Mennonites in the old colony. Mrs. Pauls has visited the castle of the Barons of Liechtenstein and also his family grave. On the grave stone of the mother of the family tomb in Liechtenstein is the inscription: ‘She died of a broken heart because of an unruly daughter.’ Ms. Pauls says that Justina’s brother Anton visited her several times in Russia. Mrs. Toews (born 1894, she lived in Curibita) also knew about this story. In addition, Maria Peters (1881–1949) related how she, that is to say, the descendants of the Peters family, had been decried as Jews in the Nazi era because of their ancestral origin.”23

One can immediately see that this version of the legend is another classic attempt to connect early Mennonite ancestry to some sort of nobility. A connection to the royal family of Lichtenstein seems highly unlikely. Additionally, it is claimed that the above excerpt comes down through the descendants of Peter Peters and Justina Nowitzky. This is not correct. The people mentioned were descended from Jacob Peters and Helena Bergmann. Helena’s parents were Anton Bergmann and Justina Nowitzky. This might explain the origin of the name Anton: he was the husband of Justina Nowitzky, not her brother. Justina Nowitzky’s family is well-documented24 and does not contain any Lichtenstein nobility!

Immigration Stories

There are many legends of families travelling from Prussia to Russia by foot, often pushing a type of wheelbarrow or pushcart. Historian David G. Rempel states that these stories are not true and an exaggeration of the hardships that immigrant families went through.25 There are also many legends claiming that a particular ancestor emigrated directly from “Holland” to Russia. These are all simply not true. There is no evidence whatsoever that any Mennonites emigrated directly from any Dutch territory to Russia, even via Prussia. We know the village of origin of nearly every family who immigrated to Russia.26

An example from the “Pioneer Portrait of the Past” series which ran in the Altona Echo for several years illustrates both of these categories of family legends.27 The article reads: “Our great, great, grandfather Falk walked from Holland to Germany and from there to Russia. To cover the distance by foot from Germany to his destination in Russia took him two years. Then, when the Mennonites migrated from southern Russia to Manitoba, he was among the pioneers. He died at the age of 108 years.” Heinrich Falk did indeed immigrate from Russia to Manitoba and did reach the advanced age of 96 years, but he was born in Schönwiese, Khortitsa colony, Russia in 1799.28

Another common immigration theme is that of an ancestor of the family immigrating alone as an orphan. There certainly were orphan children who immigrated. However, records show that they immigrated with their foster families or relatives. In some cases, the so-called orphan children had lost a father and immigrated with their mother and stepfather and therefore were not really orphans.

Conclusion

I have presented just a few examples of the various family stories which I have collected over the years. Although entertaining, most are far from accurate. Myths and legends are part of our Mennonite culture and they are worth collecting and investigating. Unfortunately, some of these have been incorporated into published genealogies or appear in the GRANDMA database and are often treated as if they were historical fact. If you have a family myth or legend to relate, please contact the author.29

- See www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/ for a large collection of early genealogical material. ↩︎

- Glenn Penner and Tim Janzen are the administrators of the Mennonite DNA Project. For more information see www.mennonitedna.com or contact the author. ↩︎

- For a translation see: www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/1.Gueltige_Numbers_and_Notes.07.27.17.pdf. A good scan of the original page can be found here: https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/cong_15/prz/IMG_1818.JPG. ↩︎

- Horst Penner, Die ost- und westpreussischen Mennoniten in ihrem religiösen und sozialen Leben in ihren kulturellen und wirtschaftlichen Leistungen (Weierhof, Germany: Mennonitischer Geschichtsverein, 1978), 326-327. ↩︎

- This refers to the Red War. ↩︎

- Mennonitische Rundschau, 7 May 1941, 6. Translated by the author. ↩︎

- Geschlechtsregister (Michael Loewen) copied 15 Feb 1940. I would like to thank Dave Loewen (Abbotsford, BC) and Jason Loewen (Woodbury, MN) for providing me with family copies of this document. ↩︎

- See www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/ for a large collection of early genealogical material. ↩︎

- Christian Neff and Nanne van der Zijpp, “Hansen, Georg (d. 1703),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online [hereafter GAMEO], 1956, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Hansen,_Georg_(d._1703). ↩︎

- Marriage Records of the Flemish Mennonite Church of Danzig – 1706. A scan of the page can be found here: https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/cong_310/bdms17/0093.jpg. ↩︎

- Catholic Church records of Tiegenhagen, West Prussia. ↩︎

- Records of the Mennonite church of Tiegenhagen, West Prussia. Various transcriptions and scans can be found here: http://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/. ↩︎

- These are found in the Records of the Frisian Mennonite Church of Orlofferfelde, West Prussia and the Lutheran church records of Tiegenhof, West Prussia (which contain Mennonites after 1800). ↩︎

- See “Michael Blatz 1760,” Ancestry.com Message Boards-Surnames-Blatz, 6 Dec. 2000, https://www.ancestry.com/boards/surnames.blatz/11.12.13/mb.ashx. ↩︎

- More information about the Genealogical Registry and Database of Mennonite Ancestry [hereafter GRANDMA] database can be found at: https://www.grandmaonline.org/gmolstore/pc/Overview-d1.htm. ↩︎

- I would like to thank Maureen Hiebert (1942–2017) of Winnipeg for forwarding her email correspondence regarding the origins of the Mennonite Blatz family. ↩︎

- Karl Stumpp, The Emigration from Germany to Russia in the years 1763 to 1862. (Lincoln, NE, American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 1997), 395, 883, 885. ↩︎

- Odessa State Archives f.6, op.5, d.2. ↩︎

- Tim Janzen, “Joseph Nowitzky, the Jewish Mennonite,” Preservings 25 (2005): 68-70. I would like to thank Tim Janzen for extensive discussions regarding the Nowitzky family and DNA testing. ↩︎

- 1801 Census, Chortitza colony, South Russia Odessa Archives, f.6, op.1, d.67, extracted by Tim Janzen, http://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/Chortitza_Mennonite_Settlement_Census_September_1801.pdf; Nov 1807 Chortitza colony census, State Archive of Dnipropetrovsk Region [hereafter SADR], fond 134, op. 1, d. 175, transcribed by Tim Janzen, http://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/Chortitza_Mennonite_Settlement_Census_November_1807.pdf; May 1811 Chortitza colony census, SADR, fond 134, opis 1, delo 299, transcribed by Richard Thiessen, http://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/Chortitza_ Mennonite_Settlement_Census_May_1811.pdf; May 1814 Chortitza colony census, SADR, fond 134, opis 1, delo 406, transcribed by Richard Thiessen, http://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/Chortitza_Mennonite_Settlement_Census_May_1814.pdf; Oct. 1814 Chortitza colony census, SADR, fond 134, opis 1, delo 405, transcribed by Richard Thiessen, www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/Chortitza_Mennonite_Settlement_Census_October_1814.pdf; Dnepropetrovsk Archives, fond 149, file 498, which contains an October 1816 census for the Chortitza colony (transcription in the possession of the author). ↩︎

- Odessa State Archives, op, 1, d. 201. ↩︎

- For more information see the GRANDMA database: www.grandmaonline.org/gmolstore/pc/Overview-d1.htm. ↩︎

- Johann Epp, Gedenke des ganzen Weges… Band 1, (Lage: Logos Verlag, 2000), 404. ↩︎

- For more information see the GRANDMA database ↩︎

- David G. Rempel, A Mennonite family in Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union, 1789-1923, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002). ↩︎

- See, for example, Benjamin H. Unruh, Die niederländisch-niederdeutschen Hintergründe der Mennonitischen Ostwanderung im 16. 18. und 19. Jahrhundert, (Karlsruhe: self-pub., 955) or Peter Rempel, Mennonite Migrations to Russia 1788–1828 (Winnipeg: Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 2000). ↩︎

- Elizabeth Bergen, “Pioneer Portrait of the Past (160): Heinrich and Justina Falk (1898),” Altona Echo, 25 Jun 1979, 8. ↩︎

- For more information see the GRANDMA database. ↩︎

- Contact the author at gpenner@uoguelph.ca. ↩︎