Johann Wall

Conrad Stoesz

One of my favorite collections at the Mennonite Heritage Archives is the Johann Wall fonds.1 The collection includes a diary written from 1824–1860 by Johann’s father, Jacob, a photo, portion of a blueprint for a mill, financial records, school records, and a map. If stacked together the materials would be approximately twenty-two centimeters thick.

Jacob Wall (1850–1909) was born in the village of Neuendorf, Khortitsa colony to Jacob Wall (1807–1860) and his second wife Helena Neufeld (1817–1903). Johann was the third of three children born to Jacob and Helena Wall. Jacob’s first wife was Judith Dueck and they had seven children together.

As a young man Johann began his apprenticeship at Hermann Neibuhr’s mill in Khortitsa. Johann’s sister, Katharina Peters, had moved with her husband (Heinrich Peters) and family to New York in 1876, and soon after moved to the Old Colony region of the Mennonite West Reserve. Katharina encouraged her brother Johann to move to Manitoba and set up a mill. Johann accepted the invitation and in the spring of 1877, he and his brother-in-law, Peter Peters, left for Manitoba. They stopped in Berlin where they did some sightseeing and had their picture taken. Johann arrived at West Lynne (now Emerson) on 30 June 1877. After some initial surveying of the situation to find a good place where the mill could be located, Johann left for Berlin, Ontario (now Kitchener) with $500 from Old Colony bishop Johann Wiebe, presumably to get supplies to build the mill. Upon return the Oberschultz, Isaac Mueller, gave Wall $1,000 for the mill. Clearly the invitation from his sister was an invitation from the community and the money from community leaders showed the high level of support for Johann and the mill. In the Wall papers there are fragile pieces of mill blueprints.

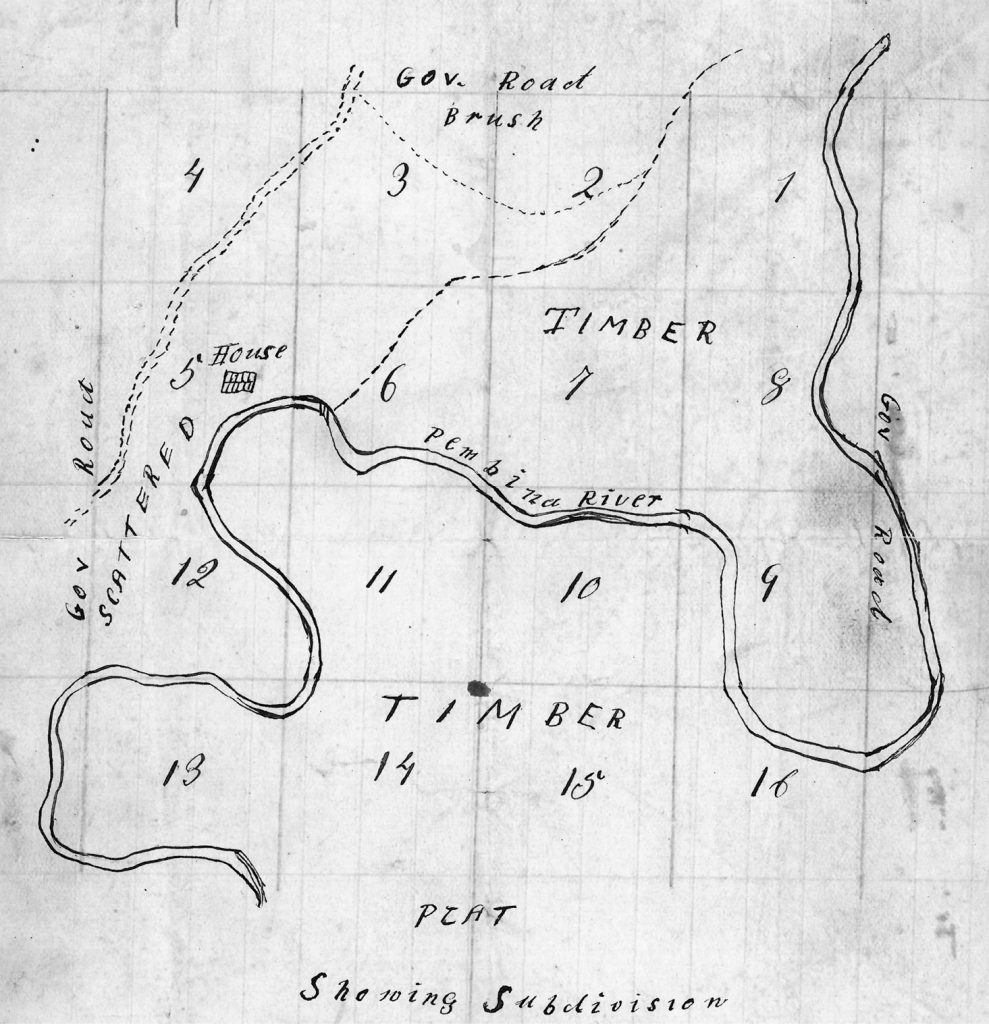

By December 1877, the mill was in operation in the village of Blumenort, lot 13, on the east end of the village, hugging the American boarder. The mill was steam-powered and had two functions: to grind grain and to power the saw mill. The West Reserve was part of the open plains where tress only grew along waterways. A map in the Wall fonds reveals that, to compensate for the lack of trees, Old Colony members bought wood lots in North Dakota, some as little as a mile from Blumenort.2 Trees were cut in North Dakota over the winter and then hauled to the mill to be made into lumber for the community’s building needs. Johann Wall’s map is for a parcel of land that has the Pembina River meandering through it, a bit of brush on the northern sections, with other sections filled with timber. The map also shows trails, the government roads, and even a house. The land description is NE-12-163-55, which is about five miles south, south west of Blumenort. At one point the Old Colony Mennonites owned over 1,350 acres of timber in North Dakota.

The Blumenort mill ground grain by day and sawed logs by night. During the first years in Manitoba, Mennonites struggled to survive and the mill owners extended credit to Mennonites for flour and wood. The saw dust was collected and used in the homes as a coating over the dirt floor. The saw dust had practical but also aesthetic purposes: mill workers kept the darker and lighter saw dusts separated in order that women could use these different shades to make patterns on the floors in the living and guest rooms of their homes.

Along with the mill, Johann acquired 480 acres of land in the Hague-Osler Reserve and 960 acres in the Swift Current Reserve of Saskatchewan. He farmed two and a half quarters of land in Manitoba until November 1895, when he sold his land to his three neighbours and bought a farm west of Gnadenthal (8-2-3W) for $8,500 from J. J. Livingston. In 1898, Wall moved the mill close to Gnadenthal and converted it to a wind-powered mill for grinding grain. Why was the mill converted to wind power? Evidently the need for lumber from the mill had decreased over time. This assumption is supported by the fact that, starting in the 1890s, Mennonites had begun selling their wood lots. Presumably, the best trees had already been taken, the need for lumber was reduced after the initial settlement period, and new rail lines brought competing purchasing options into the community. With less lumber being sawed, there may have been less fuel to power the steam engine, thus encouraging the conversion to a more readily accessible power source.

Wall died in 1909 and his wife in 1927. Their son John was managing the estate when he died suddenly in 1932. A new executor, W. C. Miller, was appointed, but due to the size of the estate and poor economic conditions, winding up the estate took a long time. The process was almost completed when Miller died in 1959 and Jacob Rempel was chosen to complete the process. Rempel donated the materials to the archives in 1975 and 1976.3

I find the Wall fonds interesting because of the variety of materials it contains. The old Jacob Wall diary, the once mysterious map and blueprints, along with financial and educational materials, makes this fonds more diverse than many others. For more details about the Johann Wall fonds visit our website.

- The term “fonds” is a technical archival term that refers to the materials collected by a person, family, or organization through the course of their lives. The archival term “collection” refers to an artificial grouping of materials such as a scrapbook of newspaper clippings about the Royal family. ↩︎

- For further discussion on the wood lots see Bruce Wiebe, “The Timberlots of the Manitoba Mennonites in St. Joseph Township, Pembina County, Dakota Territory,” Preservings 27 (2007): 47-52. ↩︎

- For more information, see Johann Wall fonds, Mennonite Heritage Archives; Elizabeth Bergen, “Steam mill built in Blumenort,” Red River Valley Echo (January 24, 1973): 4; John Dyck, ed., 1880 Village Census of the Mennonite West Reserve (Winnipeg: Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 1998); Lawrence Klippenstein, ed., Resources for Canadian Mennonite Studies: An Inventory and Guide to Archival Holdings at the Mennonite Heritage Centre (Winnipeg: Mennonite Heritage Centre, 1988), 101-104; Jacob Rempel, “The First Steam-operated Flour Mill on the West Reserve,” in Manitoba Mennonite Memories 1874-1974, Julius Toews and Lawrence Klippenstein, eds. (Altona, MB: Manitoba Mennonite Centennial Committee, 1974), 43-48. ↩︎