Reminiscences of the Past

Abraham P. Isaak

On the face of this earth, where generation after generation arises from finiteness and passes into infinity, I also, as one entering the foyer to eternity, first saw the light of day on 31 December of 1852 at six o’clock p.m., in the village of Schoenau in the territory of Molotschna in southern Russia.

I was tenderly nourished by my mother through babyhood and lovingly nurtured and cared for by my parents as a boy. In my sixth year, which was a very young age for a child of that era to begin school, I entered an elementary classroom where I persevered for six years. Although not at the beginning, but little by little, though not with outstanding aptitude, my learning ability improved, to where my studies became pleasurable to me instead of drudgery.

This good fortune to reside in my parental home was not to be mine to enjoy for long. In my twelfth year my dear father passed away at the age of fifty-four. According to my mother he died of consumption1 with a very strong desire to enter the mansion of eternal rest. For three years after his death my mother, together with us as children, remained on the farm; the management and work undertaken and directed by my two older brothers, John and Peter.

After these two boys married and established their own homes, mother deemed it necessary to dispose of the farm by public auction, stock and implements included. Mother moved to Abraham Friesens, her second oldest daughter’s place, where she made her home. In my fifteenth year I had to leave my parental home and found refuge in the servant’s quarters as a farm hand at my uncle Kornelius Plett, in Kleefeld, who gave me employment through harvest time till November 11. After that my cousin Gerhart Goossen of Lindenau hired me, again as a farmhand. This contract remained in effect for one year.

Before the year ended Gerhart Goossens, together with seven others, purchased a block of land from a nobleman and moved ninety miles away from the mother colony. I moved along with them to the new colony, which they named Gruenfeld. After the contract with Goossen expired I found refuge and employment at Frank Froeses, in Heuboden, for another year, again as a farm laborer. [The] Froeses lived about five miles from Gruenfeld. Although not washed from all faults and vices as pure as father Froese desired, thanks to his good nature we nevertheless remained affectionately inclined one toward another. “A true friend is a staff acting as a support and regulator.”

After the year’s service for father Froese was ended, the newly formed village approached me, through the instigation of Gerhart Goossen, my former employer, about something that I had never thought of before, and must have seemed strange to almost everybody else as well, and that was whether I would take on the job as a teacher for the children of Gruenfeld. And that’s how it came about. I turned from a stable-hand to being a schoolteacher! I felt, as a result of this change, quite lifted up, but on the other hand considering my own lack of education, humbled and inadequate, wondering if I was really cut out for this job. Acquiring various teaching manuals I studied diligently. To obtain the respect of the children I refrained from virtually all association with other youth. My school teaching was my sole occupation to the exclusion of every other diversion. I had never before in all my life experienced any occupation that proved to be so pleasant. I retained this job for four winters and the fifth till Christmastime.

Though school affairs were my chief joy and delight, the management of which I pursued diligently, I nevertheless was not immune to the Creator’s instilled inclinations that He has placed into the heart of man. With this inclination strong within me I fell in love with a young maiden by name of Margaretha, daughter of Peter Loewen. We were united in marriage on December 26, 1873. This change in my life, thanks to God, we are privileged to continue to live in, right up to this present time.

To the displeasure of the village congregation I deemed it necessary to give up teaching. My father-in-law, a widower for the third time, was in the process of marrying a widow Esau from the town of Neuosterwick, some sixty miles from my father-in-law’s estate. As newlyweds we were to reside on my father-in-law’s farm. This would obligate my dear Margaretha to remain alone with the Russian servant who was in charge of the cattle and sheep, while I taught school during the day, a situation we deemed as being far from ideal. Also at this time negotiations were already in progress to move to America.

The Russian government was pressured by its people to change existing laws. Tsarina Katrina (Catherine), who had invited the Mennonites to move to Russia from Prussia, promised them religious freedom as well as exemption from all military service. This privilege was enjoyed for seventy or eighty years. The changed laws required the Mennonites to join the military, or in lieu of that, engage in forestry service. This tradeoff from military service to forestry service was granted to the young men through the benevolence of the Russian government. If this still did not find acceptance they were at liberty to emigrate. This was indeed praiseworthy of the government of that time.

In 1873 this latter prerogative was exercised and a delegation consisting of David Klassen and Cornelius Toews was dispatched to Canada. They found the Canadian government very receptive to the idea, consenting to help in defraying the emigration costs and granting the Mennonites the same religious liberties that they had enjoyed at the time of their immigration into Russia. The Canadian government set aside eight townships for this purpose.

In the beginning of 1874 the business of selling their farmland began in earnest. Some was sold to the Russians but most of it went to Catholic and Lutheran Germans. Their other chattels were disposed of by public auction, also for a good price. This constituted a busy time. Several, to save time, clubbed together, brought their chattels together to one place, putting numbers on the articles to know what belonged to whom. The sales were held almost daily through the beginning of the New Year, creating busyness for everyone. These sales were held on the property of those who had moved away from the mother colony and located elsewhere. The buyers at the sales were mostly non-Mennonites, but there were also those Mennonites to whom our emigration was a laughing matter. Now, fifty years later many, many have deeply regretted and bemoaned the fact that they too did not also forsake their beloved Russia and move to a free North America to seek a new homeland. This would have saved them many hardships and heartaches, even death from the whole Russian mismanaged economic and political revolution and upheaval that ensued in the following years.

When finally everything was sold and all preparations for the journey completed, we, sixty families in total, of our Kleine Gemeinde group, seven families stayed back that came later, boarded the steamship on the Dnieper River, the fourth of June, 1874, traveling downstream to Kherson where we stayed overnight. The following morning we got on a different ship to Odessa, a harbor city on the Black Sea in Russia. On June 6 at 9:45 we boarded a train, traveled through Austria to Breslau in Germany. At the Austrian border our passports and also our chests and trunks were examined but nothing was found that did not pass. From the Austrian border we traveled through her cities, Tarnopol (current-day Ternopil-editor), Lemberg (Lviv), and Krakau (Kraków) to Oswivim (Oświęcim) on the Prussian border where at six p.m. we disembarked and spent the night. In the comfortable, cool evening air my wife and I went for a walk in the open fields and gardens. The beautiful blooming, sweet smelling, ambience breathed upon us its fragrance. This part of creation, the workmanship of God, gave us more pleasure than did the fancy, architectural, engineering handiwork of man that we saw in the large cities. We had no children at this time so this was for us virtually a honeymoon. We were as carefree as during our school years. Parents with children carried a much larger responsibility and were not as buoyant. What we realized only in a small measure at this time was that in our new home it would be quite different.

Leaving Oswivim on the ninth of June at 8:20 in the morning we went directly to Breslau where we arrived at three o’clock p.m. At 10:20 p.m. we boarded the next train, which took us to Berlin where we arrived on June 21 (in transit we had switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar). The twenty-second of June we stepped off the train and went to the waiting room. Here two young men who were going to take us into their care met us, but they and we noticed, much to their embarrassment, that a different shipping company than the one on which we were booked employed them.

Presently a Mr. Spirgo, the leader of our group of emigrants met us and we were taken in handsome carriages through the beautiful city of Berlin, the capital of Germany, to the railway depot, where, after Spirgo took our tickets, we boarded the train for Hamburg, a large seaport on the North Sea, the place of our departure. After dinner on Monday, June 22 we arrived at Hamburg where Meger and Company supplied us with living quarters in a large, four-story Emigration Building. Here we met other Mennonite emigrants from our area who had left their homes before we did and had stayed in these quarters for a few days already. Up to here we had traveled at our own expense but from here to Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, the Canadian government paid our fare, $34.00 per person directly to the shipping company.

At ten o’clock a.m. on June 26 we left Hamburg on the steamship Elbe, crossed the North Sea and landed at Hull, England, on Sunday, the twenty-eighth of June at two o’clock p.m. Because the English are more religious than the Dutch or the Germans they kept the day of rest and as a consequence our baggage stayed on the ship till Monday. We, together with Peter Duecks, Mrs. Dueck is my wife’s sister, went for a walk in the English city to while away the time. Due to the absence of commerce on Sunday, almost absolute quietness reigned in the city. We met very few other pedestrians. At one point a total stranger stopped to admire the Duecks’ baby that Peter was carrying and gave it an affectionate kiss.

Early Monday morning, the twenty-ninth of June, at seven o’clock a.m. our chests, trunks and crates were transferred to baggage cars. We were invited to the hotel for a delicious breakfast of white bread, buttered and served with coffee. The good, nourishing, rye bread that was our staple in Russia was not available in England or elsewhere during the entire trip. Their digestive organs are doubtless too weak and incapable of handling such roughage. After breakfast we hurried to the railway station where Spirgo, our leader, attending to his responsibilities came into the coaches and warned us not to allow the children to poke their heads out of the window because we’ll be traveling at lightning speed. That’s how we sped on, through field and valley, high bridges and through long, dark tunnels. The fiery steed carried us for seven hours, as though stung by horse flies! Confined to the tunnels, the steam and smoke frightened and almost suffocated us. The engine seemed to be spurred on to greater speed to get out into the open again. It appeared to us that such speed had never been our lot in Russia or Germany. England’s transportation moved at much greater velocity than the countries we had traveled through up to this point. Upon our arrival at Liverpool we were assigned our night’s lodging and after supper we retired for the night and enjoyed a comfortable night’s rest.

On the thirtieth of June, after breakfast we made our way to the huge seaport on the Atlantic Ocean, entrusted its captain, and ourselves to the ocean steamer Austria and to our God and commenced our journey across the mighty Atlantic Ocean.

As is common to man, even as did the children of Israel in the wilderness, some of us murmured against Spirgo, blaming him for some of the poor quality food that was served on board. However, this patient man, knowing quite well what kind of weather we might encounter on the open seas, comforted us by telling us that tomorrow you will be satisfied with the ship’s fare. The tempestuous storm that came upon us already the first three days of our journey made virtually everyone seasick. Instead of desiring better food we lost the stomach’s contents over the tongue.

Both on land and on the railroad it looks as though man is lord over nature but when on the wide-open sea, once the elements begin to rage uncontrollably, the picture changes. It stirred pity in us to see so many fathers, mothers and their children lying helpless with seasickness. Together with a few others who were not seasick, we endeavored to serve those who were smitten. Doubtless we could have helped even more. The sailors tried to console us, stating that it was merely windy, not stormy. The fourth day the storm subsided and the passengers became happier and their appetites returned. We were happy when we heard that those who followed us several weeks later on the same ship had smoother sailing. The sailors had referred later to the previous voyage as a stormy one, especially so on the first part of the trip.

After a seventeen day journey, stopping at Newfoundland and also at Halifax to unload freight we arrived at Quebec City, Canada, in the early afternoon, where we anchored and disembarked, safe and sound. God be thanked that we finally landed safely on Canadian soil in North America. That is all except for two children that died en route and were buried at sea. Katrina, a daughter of Frank Froeses and Jacob son of Jacob Friesens became sick, died and were committed to the sea.

After leaving the dock we were transferred to the main waiting area at the train depot. That afternoon we spent a refreshing time of recovery till early evening, walking in the beautifully blooming, artistically arranged flower gardens on the outskirts of the city. Beautiful indeed is nature and life. Only man is corrupt.

At 8 o’clock in the evening we boarded the train for Montreal where we arrived Saturday evening, the eighteenth of July at 7:45 p.m. After a good supper we boarded the next train to Toronto. Sunday morning, the nineteenth, we disembarked at eight a.m., but due to the fact that it was Sunday we had to unload our own chests and trunks. Here members of the Old Mennonite church greeted us. We worshiped together with them, their minister serving us with the Word.

These Mennonites, knowing both the Dawson, Canada, and the US (Duluth) routes, though they knew that it would prolong our journey, negotiated with the government to our advantage. For an additional two dollars per person we could travel to Manitoba by way of Minnesota, USA. This avoided the Dawson route through Quebec, Ontario and eastern Manitoba, a route that entailed a lot of riding on wagons on extremely rough corduroy roads through muskeg, swamp, floating on shoddy canal barges while crossing countless, small, mosquito infested lakes, where baggage, due to lying in water in the bottom of the barges would have been spoiled. This route was almost impossible for women and children to navigate, there being no railroad as yet, neither proper resting accommodations nor places to eat.2 Finally on July 12 at noon the welcome news reached us that we were being routed around through the USA.

Our baggage was loaded onto boxcars and we boarded coaches for the six hour journey to Collingwood, on the shore of Georgian Bay which forms part of Lake Huron, arriving there at nine o’clock p.m. The people and language were foreign to us and here we were, feeling quite lost, without guide or interpreter. Fortunately the ship and train personnel knew exactly what to do and an hour later saw our baggage and us safely transferred onto a ship and we lifted anchor, heading for Duluth, Minnesota. The twenty-third of July we reached a waterfall where we passed through locks, which lifted us in three stages from Lake Huron onto Lake Superior. After being lifted through the locks at Sault Ste. Marie, we were back on the open sea. Such and many other noteworthy things we observed and experienced on our trip.3 Most of us were born and raised on the steppes of southern Russia and were unfamiliar with either railways or steamships, having never traveled on either one or the other.

At midnight between the twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth we arrived at Duluth, took what luggage we usually carried with us and went into the Emigration Building, staying there overnight. It was Sunday so Uncle Abram Loewen conducted a worship service with us there.

Monday afternoon at one-thirty we boarded the Pacific Railway train and headed for Moorhead, Minnesota, slept fitfully during the train ride and disembarked at six o’clock in the morning on Tuesday, July 28. We stayed outside until four o’clock in the afternoon when we boarded a barge that was towed behind a steam powered tugboat and began the journey down the Red River. This river flows north between wooded and sometimes open banks. The trip down the Red River was, because of the countless hoards of voracious, biting mosquitoes, distinctly lackluster. The torture they inflicted on us in the open flatboat was something we had never before experienced. “No wonder that Pharaoh released the children of Israel from their bondage after the plague of flies,” (Ex. 8:24) he soliloquized. Eventually, at nine o’clock p.m. on July 31 we arrived in Winnipeg.

Here William Hespeler, a government appointed guide welcomed us and took us under his wing. As interpreter he advised us on what to buy that would prove most important when beginning our new life in a new country.

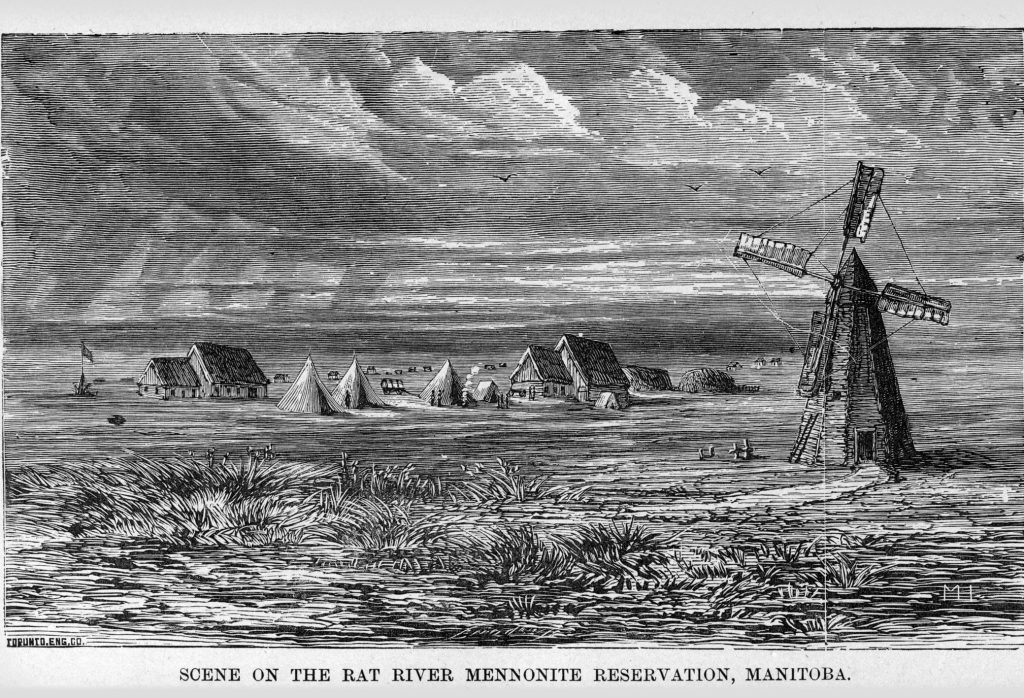

Saturday, August 1 we left Winnipeg and headed back up the mosquito-infested Red River to the point opposite the land, the eight townships, on the east reserve, that the Canadian government had allocated for Mennonite settlement. This land was approximately ten miles east of the Red River.4 Here, August 2, 1874, thanks to a loving God, our journey by land and water was safely concluded, except for the ten miles that required traveling by foot. Mr. Hespeler had hired ox carts and Metis at the Emigration Office to freight the crates, trunks and baggage the last ten miles. A friend, Mr. Shantz, a Canadian Old Mennonite had, out of love for us, occasioned temporary shelters to be built here for the women and children, which sheltered us from the sun and from some rain.

We men struck out in different directions looking for homesteads and after having selected one, registered it with Mr. Hespeler for the sum of ten dollars.5 This material, both bulrushes and trees, of course stood us in good stead and was used to build our first winter’s home. We never ran out of firewood or water. We sold firewood to those grain farmers that throve on clean, choice, rock-free land, where water was hard to find but everything grows well if and when planted, including trees. However, when grasshoppers, drought, flood, hail or poor grain prices brought the grain farmers difficult times we were marginally better off. We even sold firewood to the poor prairie farmers.6

Having completed the legal aspects of the transaction we were ready to establish a new home here in North America. The building of a house for the upcoming winter, though our awareness of the severity of Manitoba’s winters was limited, and putting up some hay for a few head of livestock we knew would require earnest effort. This was quite a change from a honeymoon trip to the strenuous exertion needed and employed to establish an earthly existence in a new country on undeveloped, virgin soil.

My teaching career, where I had without worries dreamed away the best years of my youth, paying no attention to farming methods, did not stand me in good stead now and had to be changed immediately. Though difficult, it was not impossible. Where there’s a will there’s a way, and in spite of mistakes, failings and blunders, under the canopy of the most High, we have always somehow managed.

We, my brother Peter and I formed a partnership and filed jointly. Together, my wife and I, Peter’s wife and two children, our dear mother, sixty-one years of age and Sister Helena, age fifteen, built a dwelling of sorts, on the northwest quarter, west of the marshy creek, for the first winter. Our building materials were reeds (bulrushes), which grew in abundance in the flats close by, and some purchased rough boards and hand cut rails for walls and rafters. The reeds were tied in small bundles and placed on the roof. On the inside the cracks between the boards and rafters were pasted over with paper to keep out drafts. The underside of the rafters were lined with the rough boards and plastered with paper as well. When the boards dried out the paper ripped, losing even that bit of effectiveness. In these primitive quarters we six spent our first winter in Canada.

On November 20, in this crude hut my wife gave birth to our first child, a fine son whom we named Peter. The morning of his birth, the temperature under the bed where she lay was fifteen degrees Fahrenheit, or minus six to seven Celsius,7 The cook stove being heated to full capacity, she endured this trial well and she’s still my healthy companion, loving wife and the devoted mother of our children. The small lad, Peter, throve, growing to be a healthy, husky boy, stronger and heavier than the four boys that followed him, and is presently in his fifty-sixth year.8 As soon as the severely cold winter let up, my brother Peter and I sallied forth with our axes to cut down poplar trees, of which there were more than sufficient on our land, with which we built a log house, sixteen by sixteen, patterning it after the Russian type of structures that we were familiar with, situating it in the woods in the middle of the section on the east side. We lived in this through the early summer during which we built a second longer one for mother, Margaretha and me.9

Our meager planting of grain, potatoes and other vegetables that first year was totally demolished by grasshoppers. As a result of this disaster we had to, the following year, live on what was left in our pockets, which were by now quite empty, ours as well as other’s. Somehow we managed to survive. The government as well as the Canadian Old Mennonites gave us money and food with which we scraped through but with little room to spare.10

In the fall, 1875, the rest of the Kleine Gemeinde as well as the Bergthaler Gemeinde all came over into Canada, none stayed back in Russia. This latter group, whose Colony was situated a hundred and fifty miles from the Molotschna colony in Russia, though coming on different ships, also settled in the eight townships, east of the Red River, reserved for the Mennonites. Some English-speaking people settled in the northeasterly corner of this block of land.

There was not a mile of railroad in the province of Manitoba, nor in Saskatchewan or Alberta for that matter, and very few roads, none of them graded.11 There was not a single dwelling in the thirty miles from our house to Winnipeg at that time. Winnipeg, with a population of two thousand, was the town where we received our mail and got our groceries and other necessities. This distance we traveled by foot or with oxen.

We encountered many strange, unusual adventures in our first year’s sojourn in this new land. Looking back it now seems almost miraculous that in spite of great difficulties we were quite happy. To obtain staples with which to feed ourselves so that we could survive, I would take a load of hay, drawn by oxen, to Winnipeg, a journey of three days and two nights and consider myself fortunate to receive three dollars in cold, hard cash. When, that first winter, the whole city of Winnipeg ran out of flour we had to go to Emerson on the Minnesota border to purchase that commodity. Fortunately I did not take part in that particular feat of endurance.

This trip was undertaken in winter, again with oxen, when the temperature was just short of minus fifty.12 In forty miles there was just barely overnight shelter found for the men and none at all for the oxen. The poor animals’ noses were frostbitten but in spite of the hardship endured, men and oxen came back home bringing loads of flour and the community survived. Such are some of the homesteading difficulties encountered in a new country.

The people of the Bergthaler persuasion who had sold their land on credit fared even worse than what we from the Molotschna colony did. Though they received their money later, it did nothing to get them through the second winter. Those of us who had brought our money with us fared a little better. It wasn’t strange to see flour bags converted to trousers. During the week, available Sunday trousers were worn as underwear and the flour bag pants turned into Sunday underwear.

The second planting in 1876 yielded a small but good harvest. The grasshoppers, after cleaning up the previous year’s growth had all flown away. For the quality wheat that we harvested and hauled the thirty miles to Winnipeg with oxen, we received fifty cents a bushel, twenty-five cents in cash and the balance in supplies. Thinking back now everything really went remarkably well. We were happy and content.

Hold on! Here I come to a point where my wife’s happiness and mine came to an abrupt halt, for a while. The third winter in this new land, the thirteenth of December at three o’clock in the afternoon I left with half a cord of firewood for a steam driven sawmill, (toward what today is Steinbach) if indeed the mill could be so called, sell the wood and with the proceeds, purchase a gallon of coal-oil for the lamps, oil that cost from seventy-five cents to a dollar per gallon. It was the calm before the storm! The weather was mild to the point where one’s shoes became wet when walking in the snow.

While driving back I was suddenly, with a mighty blast enveloped in a snowstorm, a blizzard from the northwest, the likes of which Manitoba has probably not seen since.13 To keep the oxen on the trail was impossible; they simply turned their tails to the wind. I had little choice. To this day I know of no other method that I could have implemented by which I could have remained alive. I unhitched the oxen, separated them by removing the fasteners from between them and released them. I broke the crust from a snow drift with my feet, scraped away the loose snow and lay down in the scooped out hollow with my head cradled on my arm, thinking as I did that I would probably never again arise. In a short while I was entirely covered with the wildly blowing snow, quite comfortably warm at the beginning. The storm raged over me, I heard it but its force and fury had no effect on me. This was at approximately six o’clock in the afternoon. This comfort did not last long. I was wearing a fur coat, brought along from Russia, under which I remained dry but below it my body heat melted the snow, my legs and my face became wet and grew colder and colder. As I became more and more chilled I started to battle sleep. There is a saying that freezing to death is an easy way of dying. Nobody has ever verified this but I came so close to experiencing it that I have no difficulty in believing it. My growing colder and the approaching night both worked together to make it ever more difficult to stay awake. Even while thinking that I wasn’t sleeping, I dreamt that I was in a room, together with other people, warm and comfortable, even more comfortable than what normally would be the case. It took a mighty effort to tear myself away from such comfortably sweet sleep. In the sure knowledge that in this life I would never wake again, it was possible, with the help of God to open my eyes and bestir myself enough to remain awake. Had I been single I would undoubtedly have given myself over to a permanent sleep, but sympathy for my dear wife, the very thought of what she would have to go through if I remained unfound till spring, worked powerfully to help keep me awake and alive. I had no idea where I was lying. In all probability, if I died here it would be springtime, after the snow melted before they ever found whatever remained of me after wild animals devoured me. Such thoughts motivated me to endeavor to remain awake and alive.

Hours later, after the wind had died down I broke out of my snowy bed. The skies were clear, the stars twinkled and the temperature, as I found out later, stood at minus twenty-six Fahrenheit. My nose and ears immediately froze. I ran in one direction but found no house or village. Oh, how alone I felt! It seemed there was no one else in this frigid world! Who or what was it that urged me to take a different direction? Was it not God’s watchful eye over me? I had not run far in this direction when I saw a light. With great thanksgiving in my heart I ran toward the light that shone in this house. I saw that my life was saved. I arrived at the door and knocked loudly.

“Who’s there?” came from within.

“I, Abraham Isaak.”

Upon that the door was opened. I found myself at Erdmann Penners. Mrs. Penner was in confinement, hence the light at two a.m.

My nose and ears were promptly washed and rubbed with turpentine, which thawed them relatively painlessly. After giving me food I was shown to a good bed and slept blissfully.

The next morning, Schultz, who together with Penner owned a nearby store,14 took me to my brother John’s place in Gruenfeld. John wasn’t at home but had gone the one and a half miles to our farm to see whether I had arrived at home safely. John had seen one of my oxen come into the village and had brought the other one in from a nearby field. He did not find me home but to save my wife anxiety had not mentioned the fact to her that my oxen had found their way to his place. Half way back to Gruenfeld he changed his mind. If they brought me in dead, he thought, the shock would be even greater for her than if she had been told about the oxen. With that he turned around, went back and told her about it.

Till now her father’s teaching had helped her to maintain her composure. That teaching embodied the fact that even in the face of comprehensive evidence to the contrary, one must remain hopeful. All hope torn away, agony and grief left her devastated. John nevertheless had to walk back to his home and halfway there he met John D. Dueck, Gruenfeld, bringing me home. My brother John accompanied us back to my home.

Imagine the sorrowful scene! My wife was so grief stricken and comfortless that when we drove onto the yard, even at the urging of mother and my sister Helena who looked out of the window and saw me, exclaiming how I was sitting upright in the sleigh, she would not, could not believe that I was safe till I walked in the door. Thus were we given to each other anew.

This weighty experience drew us closer to God in thanksgiving and prayer. Though our understanding of conversion, repentance and peace with God was limited, insofar as we had light and understanding, by the grace of God, we had endeavored to live conscientious lives. When Bishop John Holdeman came preaching and bringing us a clearer understanding of the true meaning of being born again and living a Godly life, we were engrafted as living branches into the true vine Jesus Christ, and baptized into His church. Some months later, in 1882, I was elected into the ministry and as an ordained servant of God labored and enjoyed, more or less , this privilege till my seventy-eighth year, forty-eight years later.

Afterword: Memories of A Grandson

Grandfather suffered a stroke but lived another eight years longer. Though I remember but little of him, I do remember being at their house. Aunt Mary, Dad’s sister, (unmarried) together with Grandfather lived in a small house on the farmyard, when, as children will, I decided to run out and play. Grandfather was sitting in his wicker rocker with his legs stretched out and in my haste I tripped over his feet. He laughed. I felt offended; after all, I might have been badly hurt. I did not consider it funny. As a child I very soon forgot the incident. Years later Dad told me that as a result of his stroke he was not able to control his emotion, neither his laughter nor his crying.

I had just turned four three days previously when Aunt Mary came running to the house while we were eating breakfast to tell us that Grandfather had passed away. Of course we, my older siblings and our parents, hurried to the small house. It was my first glimpse of someone lying peacefully in bed, (he must have died from a second massive stroke or heart attack) not breathing. After looking a short while I thought of my cracklings, (Jreewe, a staple at many Mennonites’ breakfasts) which were cooling rapidly and left the others at their grieving to finish my breakfast and thought, even as I ran back that the ‘Jreewe’ would be too cold to enjoy. I think as a child I grieved more because of my spoiled breakfast than of Grandfather’s dying. Such is a child’s way of thinking. I was right, insofar as nobody, myself included, likes cold ‘Jreewe.’

Another incident as told to me by my Dad: One day while Dad and Grandfather were pitching sheaves onto the hayrack Grandfather suddenly started flailing his pitchfork wildly in the stubble and calling loudly, “Doft, come me mol halpe disse Schlange loot schlone!” (Dave, come and help me kill these snakes!) Dad looked and there wasn’t one snake to be seen, let alone many. Poor Grandfather, suffering from a severe cold, had taken some ether, a not uncommon household remedy at the time, in liquid form to try to alleviate his suffering and wound up hallucinating! Fortunately it soon wore off.

I greatly bemoan the fact that Grandfather did not keep up his biographical writing. I assume that pioneering was struggle enough to engage his time and energy, leaving little physical and mental stamina to continue chronicling what now would be extremely interesting to his posterity.

- The translator, Alfred Isaac, has add comments and clarification in the endnotes. Consumption refers to tuberculosis in today’s language. ↩︎

- Pierre Berton’s historical book, The National Dream, relates that the hardships endured on the Dawson Route were the undoing of other settlers on the way to Winnipeg, destroying health due to lack of proper nourishment and inclement weather, some succumbing to swamp related diseases and fatigue. The whole Canadian, or Dawson route as it was called at the time, was a political boondoggle, that served merely to line a few politicians’ pockets, as well as their friends’ who did the actual ferrying. ↩︎

- Grandfather never mentioned Sault Ste. Marie, either because he forgot, or it wasn’t called by that name at the time. ↩︎

- They stopped in the vicinity of the confluence of the Rat River and the Red River about five or so miles west of where the town of Niverville is presently situated. ↩︎

- Due to the fact that someone beat my grandfather by minutes in registering a choice piece of ground, free of stones, about four miles southeast of present day Niverville, near the junction of highways 52 and 59, grandfather settled for, and on, section 30, Township 6, Range 5 E in what is now Hanover Municipality, approximately seven miles farther into the bush to the south-east, a mile and a half from Gruenfeld. As a result, I, (the translator) have farmed the rocky, saline, flatland acres with plenty of trees as well as plenty of bulrushes near the slow-moving Toround Creek, for forty years. ↩︎

- One hundred and five years after grandfather homesteaded this land I traitorously sold the homestead and moved west. ↩︎

- At that time temperatures were measured in Reaumur, a unit of temperature measurement that has fallen so far into disuse that this translator cannot even find the correct spelling for the word, a unit of temperature measurement that comes closest to the Celsius equivalent. ↩︎

- Peter died prematurely at age fifty-eight due to an asthmatic attack resulting in cardiac arrest. ↩︎

- This was inadvertently so exactly on the half mile, in the middle of the section, that later when the official land survey was run the half mile line would have run through the middle of the living room. ↩︎

- Compare that with today’s opulence! It must have been extremely discouraging. ↩︎

- A few years later a rail line from Winnipeg to Emerson passed within eight miles of the homestead. ↩︎

- Translator’s conversion from Reamur to Fahrenheit. ↩︎

- That’s what grandfather thought then, we’ve seen some bad ones since. In 1941, a storm I clearly remember, a Mr. Fast, near Niverville, froze to death. ↩︎

- His store was in the village of Tannenau, approximately two and a half miles northeast of present day Kleefeld. ↩︎