The Suderman Family: Tracing Successive Generations

Hans Werner

In the book, The Fehrs: Four Centuries of Mennonite Migration, Arlette Kouwenhoven uses the Fehr family as an organizing principle to tell the story of four hundred years of Mennonite history.1 Stimulated by Kouwenhoven’s book and the idea that we can learn much about the bigger questions of history by focusing closely on the details of a single family, I will follow the trajectory of the Suderman family. The story of the Sudermans addresses not only the theme of migration, but also the vagaries of infant mortality and death of women in childbirth, the influence of decisions made by individuals and family units that had consequences not only for them, but also for their descendants, and how a family adapts to the larger scale events that enveloped their lives.

Since naming practices have usually dictated that the family name was that of the male line, choosing to focus on the Suderman family line means that the story here will also be dominated by sons, rather than by daughters, by fathers, rather than mothers. It also means that branches of the family will constantly be left behind as the focus will be on the line of Sudermans that ultimately includes the family of my wife, Diana Werner (Suderman).2

Our quest for origins necessarily ends when we run out of sources. It is not clear when the first Anabaptists came to northern Poland, but judging from one of Menno Simons’ letters he had visited a Danzig (Gdańsk, Poland) congregation in 1548.3 Dirk Philips, the first Ältester (Elder) of the Danzig Mennonite Church arrived in the 1560s before the Flemish-Frisian schism made it to Danzig.4 It is also not known when the first Sudermans arrived in the area, or when and where they became Anabaptists. For centuries, the Suderman name was associated with the history of the Hanseatic League. As a confederation of cities in northern Europe that formed a commercial network, the Hanseatic League provided markets for the guilds and merchants of their respective regions. Various Suderman families centred in Dortmund, Cologne and Rotterdam were prominent in the Hanseatic trade network going back to the thirteenth century.5 Although by the time Dutch-North German Anabaptists arrived in Danzig the Hanseatic league was in decline, trade of grain between Amsterdam and Danzig continued to be one of the most important connections between West Prussia and the Netherlands.

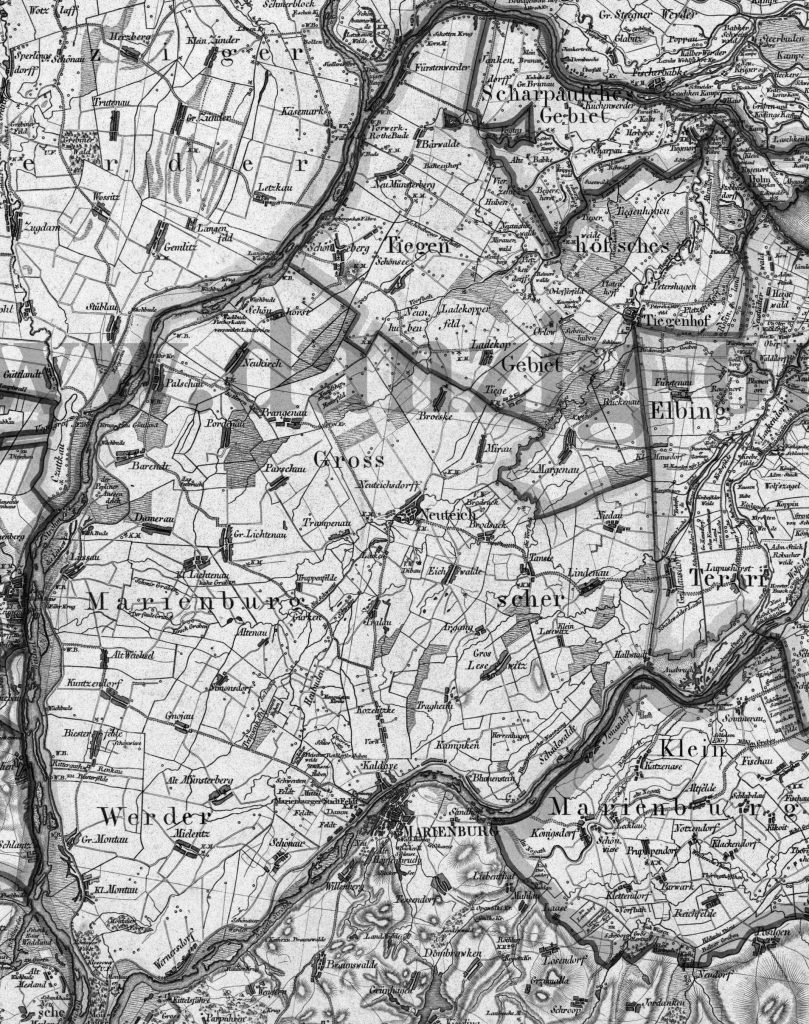

The Mennonite Sudermans seem to have been city people living in or around the cities of Danzig and Elbing (Elbląg) with a significant number involved in merchant activities. Although the Dutch or German connection of the Mennonite Sudermans remains obscure, we can trace the family line of Diana’s Suderman family as they migrated from Danzig to the rural areas of the Vistula (Wisła) delta, and on to Russia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Mexico.

Danzig

Johanna Suderman (who was born in 1657 in Rotterdam) and an Abraham Suderman (whose wife died in 1667 and he died in 1679) are the oldest Suderman entries in the Danzig Flemish Church records;6 however, these Sudermans cannot be connected directly to the line of Sudermans that we are following here. The marriage of Abraham (I) Suderman and Catharina Dunckel in the Flemish Mennonite Church in the city of Danzig, on 13 November 1701 is the first Suderman record traceable to the present generation. The presiding minister was the Lehrer (teacher) Christoph Engman who would succeed the Ältester Georg Hansen in 1703 but then fall victim to the plague in 1709.7 The split in the Mennonite church that created Flemish and Frisian congregations carried over into West Prussia where it persisted long after having subsided in the Netherlands. In Danzig, the Flemish congregation was the larger of the two. The Flemish Church’s first building was outside the city walls at the Petershagen Gate.8 The language in the Flemish church where Abraham and Catharina were married would have been Dutch, while the language at home was gradually becoming the Werder Platt (Low German) of the Vistula Lowlands. Abraham Suderman (I) was approximately twenty-one when he married, his bride was a year or two younger. There are likely gaps in the family record since Abraham (I) and Catharina’s first recorded child came some ten years after their marriage. Between their wedding day and the birth of the first recorded child, about one-half of the population of the Danzig area died from the plague. The plague coincided with the Great Northern War between Sweden and Russia and struck the Danzig area in March 1709. The number of deaths due to the plague peaked in September and October, and it was over by the end of the year. The Flemish Church lost 160 adult members and 230 children to the plague.9 The Dunckels, Catharina’s family, were also from Danzig and lived in Neugarten, an area between the primary and secondary walls of the city. Catharina’s father, Anton Dunkel, likely fell victim to the plague, since he died in 1709.10 Sometime before 1713 Abraham (I) and Catharina lived in Langfuhr (Gdańsk-Wrzeszcz), another village outside the Danzig city gates, since their younger son is recorded as having been born there.

The Danzig Flemish Church books record two sons born to Abraham (I) and Catharina Suderman: Hendrich (Heinrich) and Antonie (Anton I) born 1711 and 1713 respectively. Heinrich and Anton (I) were four and two years old when their father Abraham (I) died at the age of thirty-five. Their mother, Catharina (Dunckel) remarried two years later to Johann Tielman. There are no recorded offspring from this second marriage. Catharina died in 1737 at the age of fifty-six. Abraham (I) and Catharina’s oldest son, Heinrich, had a large family and died in 1777 in St. Albrecht (Gdańsk-Święty Wojciech), a village near the city, which may indicate the family lived there. Anton (I) married Catharina Boldt, the widow of Jacob Hamm on 25 November 1742 when he was twenty-nine years old.11

Anton (I) and Catharina’s married life occurred during a challenging time for Danzig Mennonites. The city’s economy suffered and Mennonites’ ability to forge a livelihood was under constant pressure from the guilds of the city. Mennonites in the suburbs of Danzig were primarily engaged as peddlers, cloth and spice sellers, linen weavers, and brandy distillers. In the 1750s they faced the imposition of special taxes and legal restrictions on their economic activities.12 The result was a steady migration from the city and its suburbs and a decline in the Mennonite population of the areas under the control of the Danzig city council. Anton (I) and Catharina had six children and almost all of them migrated to other areas. Arendt was baptized in Heubuden (Stogi) and in 1789 was living in Marienburg (Malbork), Heinrich died at age ten, Anna (Anke) died in Koenigsberg (Kaliningrad) at age forty-nine, Anton (II), the line we are following here, moved to the delta, Jacob became a Lutheran and moved to the Memel lowlands, and Magdalena married Gerhard Schultz, but died eleven months later in childbirth. The child also died. Anton (I) died at the age of sixty-four while his wife Catharina (Boldt) Suderman lived to be seventy-four. When the family section of the Danzig church records was begun in 1789 she is listed as being in the hospital or alms house. The hospital was a residence maintained by the Danzig congregation for those unable to support themselves and in danger of becoming beggars.13 Given that she was a widow, elderly, and with no children living nearby, Catharina’s final home was in the Flemish Church Hospital.

Vistula Delta West

Anton (II), the fourth of six children of Anton (I) and Catharina (Boldt), was born in 1746 and the only thing we know about his spouse is that her name was Elizabeth. Anton (II) appears in the village of Schoensee in the 1772 Land Census conducted when the rural areas were transferred from Polish authority to the new Prussian administration. Schoensee is a village in what was termed the Grosswerder, or large island between the Vistula and Nogat Rivers. It would be interesting to know more about what stimulated the migration from the city to the rural area of West Prussia and to Schoensee in particular, but all we know is that Anton (II) must have moved there before 1772. In the 1772 land census he is listed as owning no land and was likely quite poor.14 Anton (II) had four children. The oldest two, Abraham and Anton, were twins. Four years later the 1776 Special Census of Mennonites indicates that the family had one daughter and four sons. At the time of the census Anton (II) was in his early thirties and was a labourer. He is listed as an Eigengärtner or Eigentumer (property owner), which meant he likely owned his house and yard, but was not a landowning farmer. The census indicates his economic status as schlecht (low), which, while not sounding good, placed him in the same category as three quarters of the Mennonites in the delta.15 One of the twins, Anton (III), died at age ten in 1778 and another son died after five weeks. From subsequent church records we do know that there were two surviving sons, Abraham (II) and Aron (I). Anton (II) died in 1780 at the age of thirty-four and it is unclear exactly what happened to the two boys, who were thirteen and eight at the time, and their mother. Abraham’s (II) baptism record indicates he was baptized in the Baerwalde church in 1791 and that he was from Neuteicherwald (Stawidła); however, when he got married on 19 February 1792 he is listed as being from Pietzkendorf (Pieczewo) a neigbhouring village of Langfuhr.16Aron (I) was baptised in the Ladekopp church in 1792 and listed as being from Schoensee.17 In 1795 Aron (I) married Magdalena (Krahn) Peters, a widow ten years his senior.

Khortitsa

The years of 1795 and 1796 were eventful for Aron (I) Suderman and Magdalena (Krahn) Peters. In March, Magdalena’s first husband, Arend Peters, died leaving her with five children ranging in age from three to fourteen. Later that year she married Aron (I) Suderman; he was twenty-three, she was thirty-three. Magdalena was pregnant when they migrated to Russia and in June 1796 their first child, Abraham (III), was born in the village of Neuendorf in the Khortitsa colony in South Russia (Ukraine).18 Aron’s (I) brother Abraham (II), his wife Susanna Neudorf, and one son also migrated to Russia a year later and both families initially settled in the village of Neuendorf. Abraham (II) had one son whose descendants would move to the Bergthal colony after 1836. The Aron (I) Suderman family seems to have prospered in the village of Neuendorf. By 1811 the family had seven horses, twenty head of cattle and twenty sheep, which placed them among the most well-to-do in the village.19 In his diary entry for the 29 January 1837, the minister David Epp records that Aron Suderman is to receive additional compensation for his work as the head of the orphan’s bureau (Waisanamt) because of his age. Aron (I) died a year later on 14 February 1838.20 Jacob Suderman, a son of Aron (I) and Magdalena, married Katharina Derksen and they had four children of whom three reached adulthood. Between 1840 and 1844, Katharina died and Jacob was remarried to Justina Loewen, a daughter of Franz Loewen from the village of Neuenburg who was in her twenties, while he was in his mid-forties.21 The marriage to Justina likely resulted in Jacob moving to Neuenburg and they must have become landowners by 1847 as he is entered on a list of Khortitsa colony householders as living in Neuenburg.22 Jacob Suderman and Justina Loewen had six children of whom five reached adulthood. Jacob died on 25 August 1875 on the eve of the migration to Canada.

After his death the extended Suderman family consisted of the following members, with their approximate ages and respective families: His widow Justina (Loewen) Suderman (age 53). Her step children from Jacob’s first marriage to Katharina Derksen included: Abraham (III) (39) and his wife, Agatha Boldt, and four children; Elizabeth (38) and her husband, Jacob Braun, with four children plus two children from her first marriage to Jacob Knelsen; Maria (35) and her husband, Andreas Schmidt, and two children. The children from Justina’s marriage to Jacob Suderman included: Justina (28) and her new husband Cornelius Krahn; Margaretha (27); Franz (23), who would marry Ann Wieler six weeks after his father died; Johann (14); and Anton (IV) (9).

With the exception of Andreas and Maria (Suderman) Schmidt, the Sudermans of the Khortitsa and those from the Bergthal colony immigrated to Canada in the 1870s. After the rest of the family immigrated to Canada, tragedy claimed the life of Jacob Suderman’s daughter Maria and her husband Andreas Schmidt, who had remained in Russia in the village of Schöneberg. In an 1880 diary entry Jacob Epp records an apparent murder-suicide, with Maria found dead on the porch of the couple’s home, while her husband Andreas was found dead in the implement shed. Their two children were still asleep in the home.23

West Reserve

The extended family of Jacob Suderman immigrated to Canada in two separate movements. Justina (Loewen) Suderman arrived at Quebec on the S.S. Sarmatian on 30 June 1877. With her were two sons, Johann and Anton (IV), and daughter Margaretha. Her daughter Justina (Suderman) Krahn was on the same ship with her husband and family. The next year, the Abraham (III) Suderman, Franz Suderman and Elizabeth (Suderman) Braun families arrived on the S.S. Peruvian on 30 June 1878.24

Justina (Loewen) Suderman settled in the village of Osterwick on the West Reserve of southern Manitoba. The choice was not arbitrary since Isaac Loewen, her brother, who arrived on the same ship also settled in Osterwick. Three sons of Isaac Loewen would become storekeepers in Winkler, Gretna and Osler, Saskatchewan. Franz and Abraham Suderman settled at Burwalde, the Brauns at Gruenfeld, and the Krahns at Schoendorf.

The Sudermans became members of the Reinlaender Mennonite Gemeinde, more commonly known as the Old Colony Church. In 1880 Ältester Johann Wiebe called for a re-registration of members after church controversies erupted which, to a large extent, had arisen out of the differing backgrounds of the new immigrants. With one exception the Suderman families registered and hence are recorded in the Old Colony Church records. It seems the Franz Suderman family was never registered as Old Colony, even though the family arrived with other migrants from Khortitsa and settled in Burwalde on the western side of the reserve, which was traditionally part of the Old Colony area.25

The widow Suderman, her single daughter Margaretha, and her two young sons became farmers in the village of Osterwick. Considering that they only arrived in the summer of 1877, Justina and her children made substantial progress in their first three full summers in Canada. By the end of 1880, when a census of the West Reserve was taken, they were assessed more taxes than most of their village neighbours. They had broken thirty acres of land, owned four horses and had a total assessment of $565 compared to the village average of $476. Justina may also have brought with her the proceeds of disposing of her property in Russia.26 Her son Franz and his half-brother Abraham (III) living in the newly established village of Burwalde had young families and arrived a year later; their assessments were $381 and $386. Abraham (III) and Agatha Boldt had seven children of whom six reached adulthood and had families. A number of their older children migrated to Mexico, while their sons Abram (IV) and Franz remained in the Winkler area. Their descendants became Bergthaler members and farmed in the Greenfarm and Haskett areas near Winkler.

Johann Suderman, the older of the two sons that accompanied their widowed mother, Justina, to Canada remained in the village of Osterwick. He married Margaretha Banman in 1884 and the couple had twelve children, eight of whom survived to adulthood. Johann’s first wife, Margaretha (Banman) died in 1905 and Johann married Helen (Dyck) Siemens, with whom he had two children. Many of Johann’s descendants joined the Sommerfelder Church but some also joined the Bergthaler Church when English and Sunday School began to enter Mennonite communities. One son, Cornelius, would migrate to the Menno Colony in Paraguay in 1927. Another son, Franz, married Katharina Peters from the village of Reinland and moved there. Franz and Katharina’s son Frank was the father of Diana (Suderman) Werner. He purchased a farm between Chortitz and Schanzenfeld in the 1950s and farmed there together with his son Bruce and son-in-law, Nick Heide (Dorothy). After Bruce’s untimely death in a vehicle accident in 1974, Hans Werner (Diana) joined the farm. Frank also purchased a farm in the Neepawa area and assisted his son-in-law Cornie Fehr (Hilda) to take over that farm.

Anton (IV), who was nine when he came to Canada, married Helena Dueck in 1888. Anton and Helena may have lived in the Greenfarm area after their marriage since there is an Anton Suderman who homesteaded NW 25-3-4 on a Time Sale.27 Abraham (III)’s descendants who later lived in the Greenfarm area did not include an Anton.

Sudermans from the Bergthal colony, descendants of Abraham Suderman (II) arrived on the S.S. Nova Scotian on 27 July 1874 and settled in the East Reserve. Later they moved to the West Reserve village of Neu Hoffnung.28

Saskatchewan

By the 1890s Mennonites in the area immediately south of Winkler were facing acute land shortages. The rate of infant mortality and death in childbirth had begun to slow and families quickly became large. In 1895 land became available in Saskatchewan with the establishment of what would become the Hague-Osler Mennonite Reserve near Saskatoon. Ninety-six families left from the Winkler train station that year and in April 1900 the Morden Empire newspaper reported that a thousand people had come to see off a large group of settlers headed west.29 On 23 February 1900 Anton (IV) Suderman and his family left the Winkler area to settle in Osterwick, just east of Warman, Saskatchewan.30 His older brother Franz also moved to Hague-Osler in 1909 as a widower after his wife, Anna Wieler, had already died. The two Suderman families who moved to Saskatchewan were, in some ways, a study in contrasts.

Anton (IV) and Agatha (Boldt) broke thirty-six acres of land in their first year and by the time they received title to their land in 1902 they were cropping forty-six acres of land and had six horses and five head of cattle.31 In 1905 the Great Northern and the Canadian Pacific Railways intersected a mile from Osterwick and the village of Warman was born. The proximity of Osterwick to Warman meant the village soon faced the pressures of modernization, which threatened the village’s survival. In 1909 Anton (IV) Suderman sold his farm and moved to the Swift Current colony, which had been established five years earlier. When Anton and Agatha Boldt moved to the village of Neuendorf near Wymark, southwest of Swift Current, they were in their forties and had a large family.

Anton (IV) and Helena (Dueck) had thirteen children, ten of which survived to adulthood. Large families and the realities of farming before mechanization made for unusual family dynamics. Franz, one of Anton and Helena’s sons, married Maria Driedger. Franz died on 3 November 1918, when Maria was pregnant with their second child. The child, also named Franz, was born on 23 April 1919. On 22 June 1919 Maria married Anton (V), Franz’s younger brother, and she and Anton (V) had ten children, all of whom survived to adulthood and had their own families. After Anton (V) died Maria would marry two more times before she died in 1982 at the age of eighty-five.32 While Anton’s (IV) brother and sister-in-law, Franz and Anna (Wieler), have no record in the Old Colony Church, Anton’s (IV) family consistently followed the path of Old Colony migrations. It was difficult to avoid the ‘world’ and railways and railway towns continued to invade Anton (IV) family’s desire to remain separate from their influence. The family tells a story about the railway coming through their land in Neuendorf. When a town was to be built, the railway wanted to name it ‘Suderman.’ Anton (IV)’s son, Johan, had the homestead entry for the land but refused this honour. The village was then named McMahon.33

Franz and Anna had seven children, but only two daughters survived to adulthood. Like his brother Anton (IV), Franz also obtained entry, the process for applying for a given quarter section, in 1899, but must have arrived in Osterwick in 1909 since he broke ten acres of land, built a house, and moved in that year. In 1911, the year he died, he was cropping thirty-six acres. Franz died in Hague-Osler in 1911 at age fifty-nine, Anna (Wieler) died in 1904 at age sixty. Having no surviving sons meant that the Franz Suderman line ended in Hague-Osler. Franz and Anna’s daughters had large families, but they were Martens and Loewens.34

Latin and South America

The extended family of Anton (IV) Suderman migrated to Mexico sometime in the 1920s. Anton (IV) and Helena (Dueck)’s family spread throughout the Latin American diaspora. Their children’s location at the time of their deaths included the Swift, Manitoba, and Durango colonies in Mexico and the Shipyard Colony in Belize. Anton (IV) died in the Swift Colony in Mexico in 1929. The 1930 Mexican Census indicates that his widow, Helena (Dueck) lived with three adult daughters, two of whom were twins, in the Swift Colony village of Rosenhof.35 In addition a son, Anton (V), is listed as living in the village of Rosenbach in the Manitoba Colony, with his wife Maria and eight children.36

Conclusion

This long view of the Suderman family shows critical points where circumstances and family decisions influenced the trajectory of successive generations. For instance, Anton (II)’s decision to move to Schoensee to a great extent determined that his descendants would move to the Khortitsa colony. His descendants, and those of his brother Abraham (II), would be the only Sudermans who did not migrate to the Molotschna colony. In turn, this also meant that their descendants would be the only Sudermans to settle in Manitoba in the 1870s. The Sudermans also demonstrated a tendency towards matrilocality—the tendency for men to move to the villages of their wives. Perhaps matrilocality explains the move to Schoensee. It is also remarkable to see how small most Suderman families were in the eighteenth century. Two Suderman fathers died in their mid-thirties, mothers died in childbirth, and the deaths of children visited families regularly. In the twentieth century, in Canada, families suddenly became large. The reduction in child mortality and the improved birth conditions, combined with the absence of birth control, meant families became large quickly and therefore, for an agricultural community, the search for land became constant. Family memory was preserved most distinctly by the Suderman family in the naming of their sons. The reader could be forgiven for getting lost among all the Antons, Abrahams, and Arons. For at least 250 years the Sudermans had an Anton in every generation.

- Arlette Kouwenhoven, trans. Leslie Fast and Kerry Fast, The Fehrs: Four Centuries of Mennonite Migration (Leiden: WINCO, 2013). ↩︎

- I am indebted to the genealogists who have transcribed and made available the family records upon which this article is based. I am particularly indebted to Glenn Penner, who provided advice and research in answering specific questions of the Suderman genealogy of the Prussian period. ↩︎

- Peter J. Klassen, Mennonites in Early Modern Poland (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press), 49. ↩︎

- H.G. Mannhardt, The Danzig Mennonite Church: Ist , trans. Victor G. Doerksen, eds. Mark Jantzen and John D. Thiesen (Kitchener: Pandora Press, 2007), 47. ↩︎

- See for instance Bruno Meyer, Die Sudermanns von Dortmund: Ein hansisches Kaufmannsgeschlecht (Pierer, 1930). ↩︎

- “Births, Baptisms, Marriages and Deaths in the Danzig Church 1665-1943,” transliterated and digitized by Ernest H. Baergen, www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/Danzig_Records.htm. I have not preserved the myriad of spelling variations found in the various sources but have rather standardized spellings to the most common recent spellings of names. ↩︎

- Ibid. and Mannhardt, 92. ↩︎

- The first Flemish church building was outside the Petershagen gate on private property, since a Mennonite congregation could not own land. In 1686 the property was transferred to the Ältester, Willem Dunkel. Mannhardt, 115-116. ↩︎

- Mannhardt, 91. ↩︎

- “Neuerrichtetes Kirchen Buch erster Teil 1789,” transliterated and digitized by Ernest H. Baergen, www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/Danzig_Family_Book_1.pdf. ↩︎

- “Anton Sudermann (1713-1777)” in Family book of the , vol. 1, p. 182, https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/cong_310/bdms19/0184.jpg. ↩︎

- Edmund Kizik,”A Radical Attempt to Resolve the Mennonite Question in Danzig in the mid-Eighteenth Century: The Decline of the Relations Between the Danzig City Council and the Mennonites,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 2 (1992): 127-154. ↩︎

- “Anton Sudermann (1713-1777),” https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/cong_310/bdms19/0184.jpg. ↩︎

- The 1772 Prussian land census (Kontributionskataster) records are located at the Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin (Dahlem). A digital image of the page with Suderman records was provided to me by Glenn Penner. An index of a 1920s extraction of these records, the Marburger Auszüge can be found at: www.odessa3.org/collections/land/wprussia. The record for Anton Zuterman is listed as being on Film 6036, Page 622, Registration Number 284. ↩︎

- Glenn Penner, introduction to “The Complete 1776 Census of Mennonites in West Prussia,” www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/1776_West_Prussia_Census.pdf. ↩︎

- “Ladekop Mennonite Church Record Book,” Image Files, Mennonite Library and Archives, p 60-61, https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/cong_306/60-61.jpg and www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/Baerwalde_Baptisms.htm. ↩︎

- Adalbaert Goertz, “1782-1805 Baptisms in Baerwalde, West Prussia,” Mennonite Family History (January 1988): 26, and “Baptisms in Ladekopp, West Prussia, 1782-1804,” Mennonite Family History (April 1989): 66. ↩︎

- “Chortitza Mennonite Settlement Census for 1 September 1801,” Odessa Archives, Fonds 6, Series 1, File 67, transcribed by Tim Janzen, www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/Chortitza_Mennonite_Settlement_Census_September_1801.pdf. ↩︎

- “Chortitza Mennonite Settlement Census for May 1811,” State Archives of Dnipropetrovsk Region (SADR), f.134, op. 1, d. 299, translation and comments by Richard D.Thiessen Thiessen,www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/Chortitza_Mennonite_Settlement_Census_May_1811.pdf. ↩︎

- “Jacob Wall Diary.” The version used here is the German transcription on the Willi Vogt genealogical website, http://chort.square7.ch/Eich/WallOr1.htm. ↩︎

- Little is known of Katharina Doerksen; she may be the daughter of Jacob Doerksen and Katarina Peters. See Genealogical Registry and Database of Mennonite Ancestry [hereafter GRANDMA] #529292. ↩︎

- “Annotated List of Chortitza Colony Householders for 1847,” State Archives of the Odessa Region, f. 6, Op. 2, d. 11519, transcribed by Glenn H. Penner, www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/Chortitza_1847.htm. ↩︎

- Diary entry for January 28, 1880 in Harvey L. Dyck, A Mennonite in Russia: The Diaries of Jacob D. Epp, 1851-1880 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991). ↩︎

- “Quebec Passenger Lists 1874-1880,” annotated by Cathy Barkman, www.mennonitegenealogy.com/canada/quebec/ quebec7480.htm. ↩︎

- John Dyck and William Harms, eds., Reinländer (Old Colony) Gemeinde Buch, 1880-1903, (Winnipeg: Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 2006), 219-3b, 237-4, 261-3b, 338-1, 408-3. ↩︎

- John Dyck and William Harms, eds., 1880 Village Census of the Mennonite West Reserve, (Winnipeg: Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 1998), 104-105. The village map on page 104 lists Justina Suderman as the resident of Lot #9, but the assessment listing from 1881 on the next page lists her assessment under Jacob Bueckert. Justina married Jacob in 1880 and he must have come to live with her in Osterwick. ↩︎

- “Land Grants of Western Canada, 1870-1930,” database, www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/land/land-grants-western-canada-1870-1930 . ↩︎

- See notes found in GRANDMA entry for Johan P. Suderman, #186469. ↩︎

- Hans Werner, Living Between Worlds: A History of Winkler, (Winkler: Winkler Heritage Society, 2006), 27. ↩︎

- Leonard Doell, Mennonite Homesteaders on the Hague-Osler Reserve, 1891–1999, (Saskatoon: Mennonite Historical Society of Saskatchewan, 1999), 25. Here it is recorded that the Anton Sudermans left for Saskatchewan in February of 1900, however, his homestead record on page 266 indicates he broke thirty-six acres already in 1899. ↩︎

- Doell, 266. ↩︎

- GRANDMA, #191548. ↩︎

- Hague-Osler Mennonite Reserve: 1895-1995, (Saskatoon: Hague-Osler Reserve Book Committee, 1995), 184. McMahon is located on NE 10-13-12 W3, which was Johan Suderman’s homestead. See: Saskatchwan Homestead Index, www.saskhomesteads.com. ↩︎

- GRANDMA, #140508 and #139768. ↩︎

- “1930 Census of Mexico—Rosenhof,” https://mennonite history.org/1930-census-of-mexico-rosenhof/. ↩︎

- “1930 Census of Mexico—Rosenbach,” indexed by Cornelius Heinrichs, Mennonite Historical Society of Alberta, https:/mennonitehistory.org/ 1930-census-of-mexico-rosenbach/. ↩︎