The Vanderhoof Expedition: In Search of Freedom

Harold J. Suderman

Since my boyhood I remember hearing references to Vanderhoof at family gatherings at my grandparents’ home in Morden, Manitoba. I learned that the Suderman family had suffered three deaths in four days during the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic while pioneering in the wilderness near Vanderhoof, British Columbia. One of the three was my dad’s older brother, John, a young man in the prime of life with a reputation for great physical strength. His death was a terrible blow, particularly to my grandfather. Another death was my dad’s brother-in-law, Peter Dyck, husband of his sister Helen and father of two infant boys. The third was Peter’s brother, Abram, who had come from Manitoba to marry another of my dad’s seven sisters, Tina.

Many years later, after my dad had passed away, my wife Wilma (née Reimer) and I visited dad’s youngest sister, my aunt Dora (Suderman) Enns in Indian Head, Saskatchewan. One of her first questions was, “Did you visit Vanderhoof?” Whenever I saw Dora in her later years, she would importune me to go and find the site where our family had pioneered.

My answer, finally, was yes. We were able to update her on our mission to look for the old homestead and to elicit more information about the time she remembered as two miserable years of her childhood. When my dad died in 1945 I inherited his old photo album with scenes of the two-year, ill-fated venture that my grandfather later not only believed had been contrary to God’s will, but also had wiped out the prosperity the family had enjoyed before in Neu Hoffnung (New Hope), Manitoba.

In the following pages I have recorded my efforts to describe what happened in Vanderhoof and to understand what motivated my grandparents and other like-minded Mennonites, mainly from the Altona-Winkler-Burwalde area in southern Manitoba and some from the Mountain Lake district of South Dakota, to leave their comfortable existences and begin again, almost from scratch.

A Fateful Decision

The Sudermans,1 like other Mennonites who had left Russia in the 1870s, were concerned about the Military Service Act of 1917, passed to boost recruitment in the war effort if needed. It gave the government the right to impose conscription on men aged twenty to forty-five and although it allowed for conscientious objectors to perform alternate service in hospitals and in other non-combat roles, it included no specific exemptions for pacifist groups like the Mennonites who had come to Canada with governmental assurance they would be exempt from any form of military service.

In early 1918 the Act was revised to exclude all blanket exemptions. Even though pacifist religious groups could still qualify for exemption, the confusion surrounding the Act heightened fears already present among Manitoban Mennonites. Many also viewed any participation in war, including as a conscientious objector, as contributing to militarism, which violated their pacifist beliefs. My grandfather, Johann Suderman, struggled with how to respond to what he considered to be a betrayal by the Canadian government. Historically, Mennonites had responded with passive resistance and a rejection of governmental authority to events of persecution or challenges to their anti-militarist stance. Non-resistance had often encouraged migration, as from the Netherlands to the Vistula Delta during the sixteenth century or from Prussia to Russia during the reign of Catherine the Great in the eighteenth century, and finally from Russia to Canada in the 1870s.2 In each instance, Mennonites were offered land and religious freedom; the latter was a promise kept for a period of time, but then in each instance rescinded in some way. In some cases, Mennonites themselves questioned this belief. For instance, in Russia, some Mennonites would come to arm themselves against the raids of the Makhnovists during the Russian Civil War, but that was a rare active response to threats of and realized violence against them and their land during a time of anarchy.3

In Manitoba, most Mennonites chose to take a wait-and-see attitude to the Military Service Act, and in hindsight, I am surprised that my grandfather did not react the same way. But he was a man of deep faith and had three sons already of military age whose salvation he feared would be compromised if they were conscripted. Still, his decision to embark on a journey of faith could not have been easy.

Both Johann (1868–1950) and his wife Susanna (née Giesbrecht, 1873–1948) had experienced firsthand the challenges and tragedies of pioneering in an unfamiliar and untamed territory. Johann was turning six when his family joined the first group of 160 Russian Mennonites on the arduous seven-week trip from Russia4 to southern Manitoba by land, sea, lake, and river. They carried little but the clothes on their backs when they got off the paddle-wheeler at the junction of the Red and Rat Rivers on 1 August 1874. Without the assistance of the Indigenous population he and his family would not likely have survived the record cold winter of 1874–75. His father, Abraham, aged fifty-two, died only seven months after arriving. Susanna’s family had also come in the first contingent of Mennonites and she lost two brothers to starvation in the first year in Canada. Susanna herself had temporarily become blind from a lack of nutrition.5

To make the prospect of leaving even more difficult, Johann and Susanna had become prosperous farmers in Manitoba by 1918 in a successful operation in Neu Hoffnung, a village near Gretna. Nonetheless, they decided to leave and re-establish themselves as far away as possible from the long arm of the government in order to live their faith in peace.

They were encouraged by Heinrich H. Voth (1851–1918), a Mennonite Brethren elder and Reiseprediger (traveling evangelist) from Minnesota.6 Voth had helped found the Winkler Mennonite Brethren Church, and although the Sudermans were members of the conservative Sommerfeld Mennonite Church at the time, some of them, including Johann, Susanna, and my father, Jake, eventually joined the Mennonite Brethren Church established by the charismatic Voth.

Voth was also committed to non-violent resistance and, to evade the American draft bill passed in 1917 (he had two sons of draft age), he joined other American Mennonites from South Dakota and Minnesota and moved his family to Winkler. Two of Voth’s daughters lived there already, one married to Aaron Dyck and the other to Peter Neufeld. Another son, Henry S., also a Reiseprediger, was soon to marry Susie Warkentin, daughter of Johann Warkentin, a Mennonite Brethren deacon in Winkler who, despite his affiliation, was among those opposed to the migration.7

A few months later, however, the Canadian Military Service Act was passed and the American families in Winkler, including the Voths, with the exception of sons Henry S. and John H., prepared to trek west to the newly-opened Nechako River Valley at Vanderhoof, British Columbia. Part of their plan was to set up a Mennonite Brethren colony.8 The Sudermans also decided to join the colonization attempt.

Destination Vanderhoof

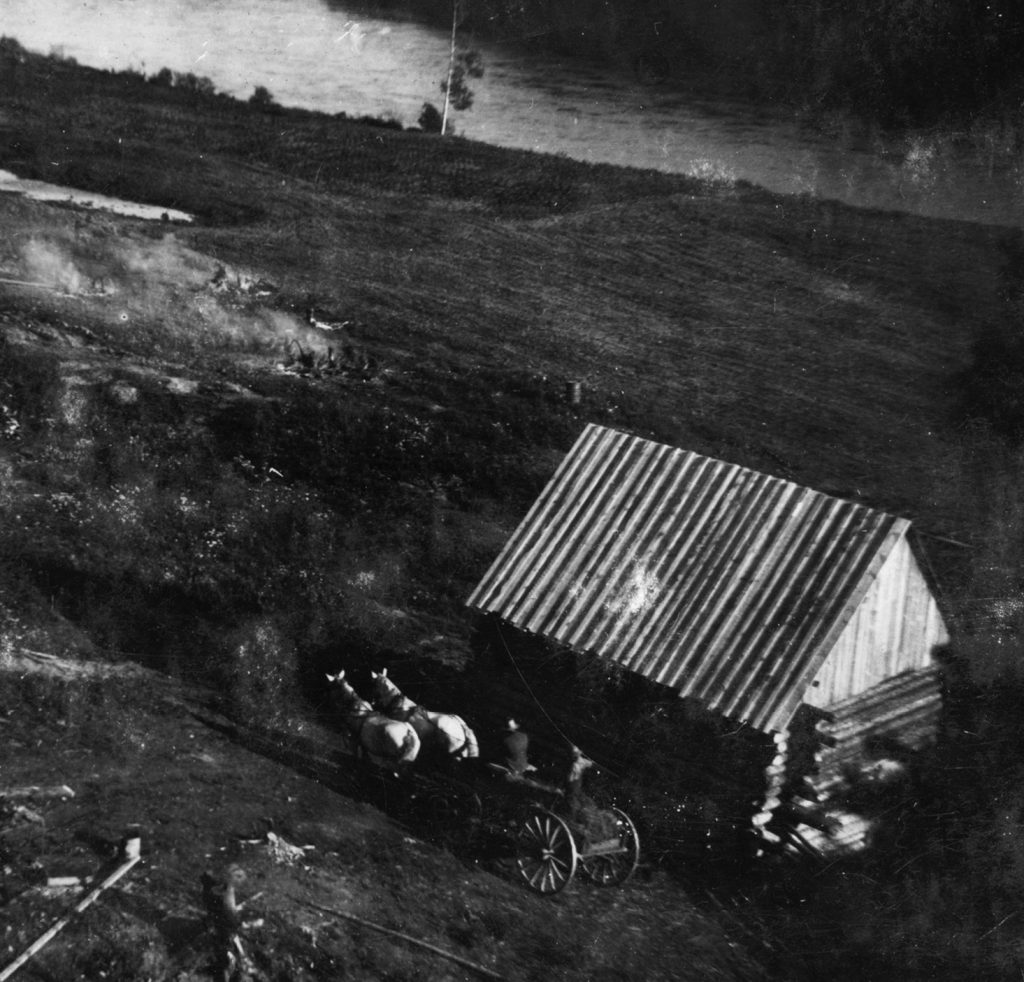

In the spring of 1918, the Suderman family set out for Braeside, about ten miles northwest of Vanderhoof, to homestead along the Nechako River, a tributary of the Fraser. Johann had scouted Vanderhoof before buying and evidently believed in its farming and economic potential. It was a northern frontier region, far from Ottawa but newly accessible by train—Vanderhoof Station had been opened in 1912–1913 by the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. Land was offered at a good price in the municipality and, with the rail connection, the settlers could foresee their grain being carried to markets as it was on the prairies.

Johann made extensive preparations for the journey. He was intent on success and wealthy enough to take along all necessary resources and equipment. He and Susanna had sold their farm and amassed everything they and their twelve children might need for the coming venture. They chartered three freight cars and one open rail car from the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and loaded them with cattle, horses, feed, furniture, farm implements, a steam-powered tractor, a car, and a threshing machine. The Vanderhoof Herald reported on their arrival that the Sudermans’ heavy steam-powered tractor was the first of its kind in British Columbia. Johann’s Model-T Ford, one of the first in southern Manitoba, was the second in Vanderhoof (the first was owned by a local doctor).9 My father, Jake, who was very independent, drove out to Vanderhoof in his own car. En route he took pictures of the majestic mountain scenery with his Kodak Model A camera, which I still have, along with his faded photographs.

Anna (Suderman) Labun, a girl of twelve in 1918, recalled that each of the freight cars required someone to ride along to look after the horses and cattle. From time to time, the train stopped so the animals could be watered. The rest of the family took over an entire coach on a passenger train and got to Vanderhoof first. When the cattle arrived, they walked them from Vanderhoof to the farm ten miles away, constructing log bridges over little gullies when necessary.10

Johann had also looked to the family’s spiritual needs and brought two enormous tents, one for shelter while they felled trees and constructed homes, and one to hold church services for themselves and the other settlers. Voth became the spiritual leader of the community and my father told me that up to one hundred people assembled in the tent sometimes, dressed in their Sunday best for the service.

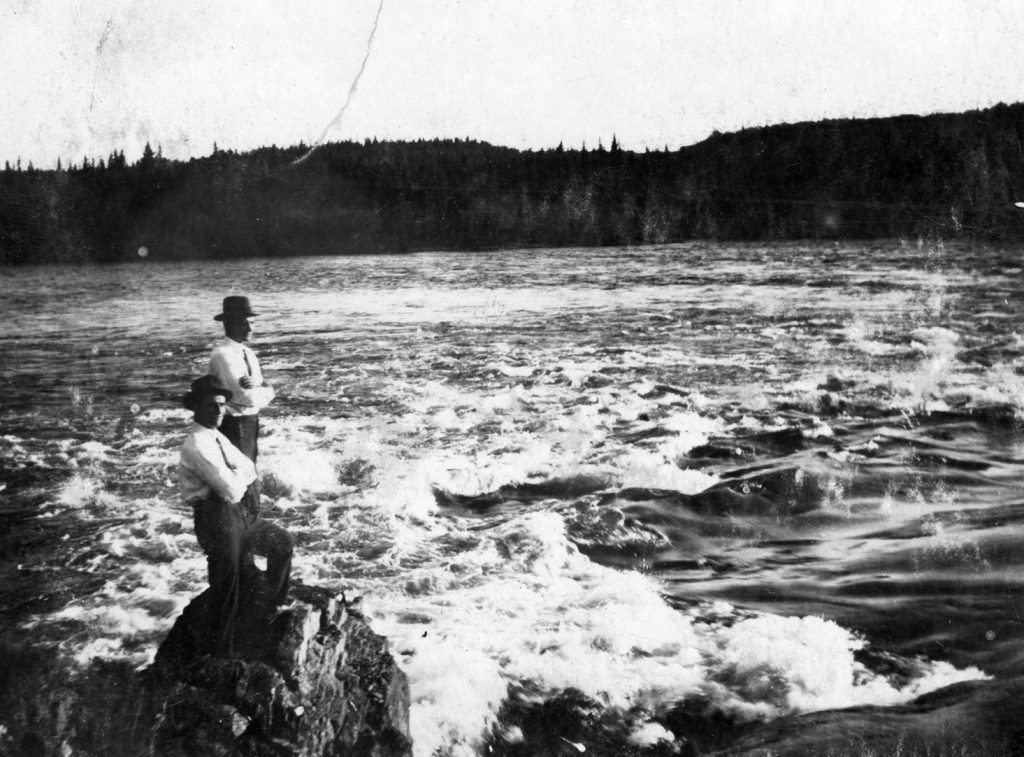

The Sudermans had bought 160 acres along the river next to the farm of Peter and Helena (Voth) Neufeld. To my Aunt Dora, aged 10, the land seemed an earthly paradise when they arrived. She recalled the bounty of fish—sturgeon, trout, and salmon—in the fast-flowing river, the beauty of the forest, and the abundance of wildlife, especially of birds warbling and darting all around. The Nature Guide to the Nechako River I consulted when we visited in 1992 confirmed her memories. Vireos, jays and thrushes, swallows, chickadees, warblers, sparrows, creepers and nuthatches, pipits, waxwings, tanagers, grosbeaks, buntings, blackbirds, and finches were among the many songbirds that were often heard before they were seen.11 Migratory birds including swans and geese also pass through the region. When the salmon ran, Dora and Anna would stand in shallow water with a pitchfork stabbing the fish and pitching them onto shore.12

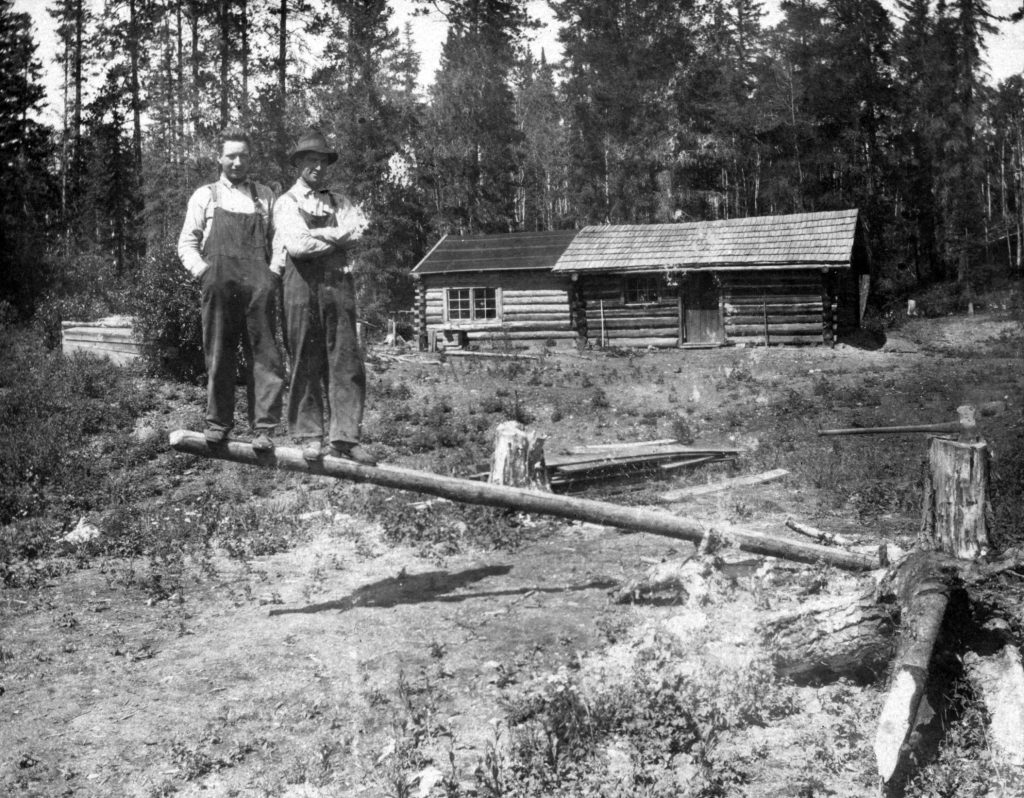

To John, Jake, and Abe, strong and healthy young men in their twenties, fell the majority of the work of clearing the land for planting. In the beginning I think they might have enjoyed their battle to bring nature to her knees! Photographs in my old album show them engaged in this Herculean struggle. In one, my father stands poised to bring down an axe over a huge stump in order to split it; in another, he and Abe prepare to lever out a stump with nothing more than a long pole; in others, the men are using the tractor or the horses to pull out stumps. In yet others, they strive to extract, by brute strength, the tractor itself, mired in the muck of a field after rain. And in the background, always, the towering forest.

I also have pictures of threshing with Johann’s steam-powered thresher as part of the scene. I have no trouble identifying my father because in the field he always wore a battered felt hat. It was backbreaking labour, for men and horses, and when I look at the pictures and remember my own days working in the fields of southern Manitoba in the 1930s, I marvel at how they had the strength to carry on.

Their first buildings were constructed out of logs. The settlers built homesteads and a church, the interior and roof of which were finished with lumber cut at the saw mill on the Voth homestead.13 The church was established a few miles north of the Nechako River and fourteen miles west of Vanderhoof, on what is still the Braeside Road.

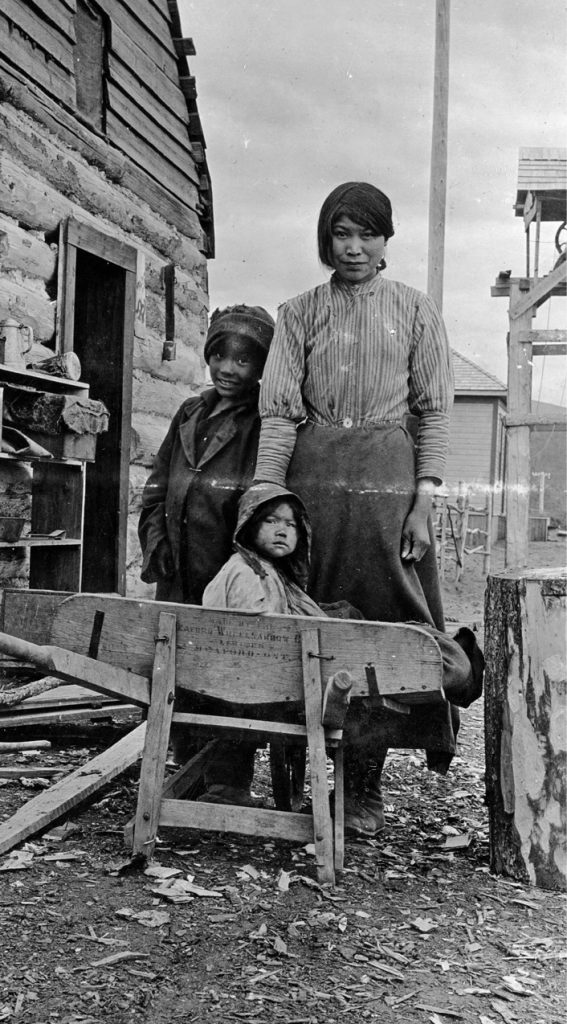

Despite some negativity from the non-Mennonites of the area towards the settlers for speaking German in town and holding church services in German and, of course, for avoiding the war effort, the Sudermans and a few other families forged ahead and created a new Braeside school district, built a temporary school house, and hired a teacher.14

If character is destiny, there is something about the Suderman character that did not shy away from a challenge and led, perhaps, in part to similar courageous ventures in the years to come. Religious zeal, a sense of adventure, attraction to the unknown, a strong will, and fearlessness were common traits. Risk did not deter them from perilous or unconventional endeavours, before or after the Vanderhoof mission, especially when undertaken in the service of faith and conviction.15

Despite nature’s mighty testing, Johann was determined and had tragedy not struck in the fall of 1918, the Suderman story might have continued to unfold there. Certainly, my grandfather would not have come to believe he had incurred God’s punishment in fleeing the law of the land.

Tragedy and Return to Manitoba

Helen Suderman had married Peter Dyck in 1914 and with their two young sons, and Peter’s brother, Abram, they followed the family to Vanderhoof in the fall of 1918. Abram and Tina were to be married in Vanderhoof by Heinrich Voth on November 3.

The little group boarded the train in Altona, Manitoba on October 18 in cold and rainy weather. As they traveled westward on their long journey they shared space with soldiers coming home from the war, and it was this that may have sealed their fate. Some of the soldiers may have been carrying the deadly influenza virus known as the Spanish Flu that ravaged the world that year, and by the time they arrived in Vanderhoof near the end of October, the two brothers were already feeling the onset of its deadly symptoms.

The virus, a variety of H1N1, was first detected in Spain. It raced through the trenches of the First World War and as war-weary soldiers returned to their home countries many carried the virus with them. By the time the epidemic had run its course in 1919, between 20 and 100 million people had died from it around the world, including 30,000 to 50,000 Canadians.16 Everywhere, the virus was most lethal to young, healthy men and pregnant women. It arrived on the Mennonite reserves in Manitoba in late October of 1918. Amongst Mennonite populations in rural Manitoba, the mortality rate was more than double (14.3) the Canadian average of 6.1 per 1,000 population for reasons as yet not understood.17

For Peter and Abram, the flu ran its customary quick and horrific course of pain, thirst, delirium, and pneumonia. Abram, aged twenty-four, succumbed on October 29, and Peter, twenty-nine, two days later. Their funeral took place on November 3, sadly the very day set for Abram and Tina’s wedding. Almost the entire Suderman family had come down with the flu, and on November 2, the oldest and strongest of the Suderman sons, John, aged twenty-five, also died.

At an outdoor funeral for the three young men, Peter Neufeld, Heinrich Voth’s son-in-law, spoke on 1 Peter 1:3-5, and D.J. Dick on Jeremiah 29:11 (the elder Voth was at a conference in Minnesota).18 Because a casket could not be built in time for John, his body was placed on the lid of one of them and reburied later. The newly widowed Helen managed to briefly come outdoors, and only Tina and Anna were well enough to accompany the coffins to the graveside where they were placed in shallow graves and covered with boards and a thin layer of earth. So many in the area were dying that material for a tin lining of the coffins could not be obtained and it was decided to remake them later and ship them back to Manitoba for reburial. In the spring of 1920, when the Suderman family gave up and returned to Manitoba, the bodies of the three young men were transported by train in sealed coffins and reburied on the prairie in the family plot of Gerhard and Anna Dyck, Peter and Abram’s parents, in the Rosewell Bloomfield Cemetery.

More deaths in Vanderhoof followed. The 67-year-old Heinrich died on November 26. He had felt his health declining after his trip to Minnesota and predicted his own life was nearing its end. In the two days before his death he built his own coffin, arranged his funeral service, gathered his family to pray, and then passed away after a nap. His young grandson, Peter Neufeld, died of tuberculosis on December 31.19 Thus within the space of two months, the Suderman and Voth families had lost three young men, a child, and their spiritual leader. They were devastated.

They laboured until the spring of 1920, but not only had the tragedies taken their emotional toll, the settlement itself turned out to be economically unviable. There was no market for their produce and no outside employment that could bring in income. My grandmother Susanna wanted to leave. She could see nothing but further backbreaking labour for her two remaining older sons, Jake and Abe. Spiritual unease followed personal misfortune and financial strain, and the Sudermans abandoned the farm they had toiled so hard to carve out of the primeval forest. The Voths did the same, returning to Minnesota while the Sudermans returned to Manitoba. Within another six months, most of the settlers had left the area and Mennonites did not homestead there again until the 1940s and 1950s.20 Ironically, the Military Service Act was never applied to the Mennonites. In the end, they had lost their right to exemption on paper but not in practice.21 My father would later say only that “it had all been a big mistake.”

Johann and Susanna lost almost everything. Back in Manitoba, they bought land near Morden next to the Dominion Experimental Farm. The farm was repossessed when they were unable to keep up with the mortgage payments. They then bought a 40-acre plot on the south edge of Morden beside the railroad tracks. The house was so close to the tracks that the vibrations of passing trains cracked the plaster. During the Depression they relied on their daughter Anna’s intermittent wages from work on another farm. Eventually the market garden provided a living for Johann and Susanna and two of their children, Susan and Ernst, who lived with them. It was said of Johann that when he went out into the streets of Morden to sell his produce (much sought after), he refused to set out until his white shirt was ironed and his cuff links were in place.22

My father, Jake, who had taught school before Vanderhoof, went back to teaching in one-room prairie schoolhouses around southern Manitoba. And so ended that short but fateful chapter of the Suderman family saga, begun with such high hopes and ending in such sorrow.

Aftermath of Failure and Change of Heart

I must say that to this day I cannot understand how my grandfather could have been so bereft of wisdom as to have sold his every acre of land and set out on such a perilous venture with an entire family dependent on his decision. I can only suppose he thought he would never go back. Presumably, belief in the righteousness of his epic undertaking blinded him to the possibility of failure; he did not envisage it and therefore made no provision for it. And perhaps he was more moved by Voth’s vision of a Mennonite Brethren colony than by reason.

Heartbreak and defeat in Vanderhoof resulted, however, in soul-searching and spiritual suffering for Johann. He believed the frontier deaths and his failure to prosper were God’s punishment for his attempt to escape the Canadian government. His thinking on this point is also somewhat of a mystery to me. Years ago I accepted his rationale at face value, but with the passage of time I ask myself: what did he identify as the sin that had incurred God’s displeasure? How could his sin have been following his conscience? Faith journeys were a Mennonite tradition when their convictions were threatened. Why would he come to think that, in this instance, God had wanted him to resist militarism but not flee it? Or did he feel he had jumped the gun, the Military Service Act not yet having been applied? He never clarified his reasoning to me and neither did my father. They didn’t talk much about the lost two years. The closest I can come to my grandfather’s spiritual train of thought is that because Canada had been good to the Mennonites, he should have found a way to abide by its laws.

In retrospect, I believe he suffered from “survivor’s guilt,” which would explain his sense of being punished, and from remorse for having prospered during the war when grain had garnered high prices, and then having tried to spare his sons while some of his “English” neighbours not only lost theirs in the war, but had been forced to sell land for lack of labour.

Perhaps he also felt that overconfidence and pride in his abilities had contributed to his downfall. Having amassed wealth once, he was sure he could do it again. The Greeks would have called it hubris; my grandfather would have interpreted it as God’s judgment for the sin of pride.

I can only speculate on the reasons for his conclusion, but I can say with certainty that his anti-militarism and rejection of civil authority (Mennonites believed war was a function of government) became less absolute after Vanderhoof.

When war was declared in 1939, my father and I tried repeatedly to enlist in the army. We didn’t want to stay behind while others risked their lives, and we had listened in horror to speeches by Adolf Hitler live on our short wave radio. To us, tuning in so far away on the vast Canadian prairie, Hitler was the voice of evil. As soon as war was declared, we went to the Fort Osborne Barracks in Winnipeg and filled out the forms and wrote the tests but we were both refused on medical grounds. This happened each time we tried until finally I went to Winnipeg to join the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in 1943 having heard that the RCAF was recruiting. I was accepted and trained in various places including Montreal and Debert, Nova Scotia, not as a pilot, because of my eyesight, but as a radio mechanic.

My father died unexpectedly in 1945 of a failed operation and when I got the news by telegram, my brother-in-law Joe Schwartz (married to my sister, Irma) and I rushed by train to Manitoba for the funeral at which we stood in uniform. I expected my grandfather Johann to be upset at the sight, but he wasn’t. He spoke kindly to us and when I came home after the war and Wilma and I lived in Winnipeg, he came to visit and offered his unconditional support for whatever I might do next. The patriarch, whose will was once iron and whose wishes few would have dared to counter, had softened.

Other returning veterans were not as lucky as I was with family and church. My family and community welcomed me back without censure while others who had enlisted as fighters or conscientious objectors were shunned by both family and church. Sometimes the families of soldiers who died were left to mourn uncomforted. My grandfather’s dilemma over militarism and pacifism mirrored the rifts in the larger Mennonite community, a difficult period of Mennonite life in Canada that has been well-examined in both academic and non-academic forums.23

Vanderhoof Revisited

In 1992, a year before Aunt Dora died, Wilma and I made it to Vanderhoof. My objective was to find and photograph what might be left of the Suderman farm. I knew it lay on the north shore of the Nechako at Braeside, just west of the Braeside-Engen ferry which preceded a bridge built nearby in 1919. If I could find what remained of the docks, I would have the farm location.

As we approached the town on Highway 16, I was struck by its remoteness! The landscape had changed little in almost a century. Majestic evergreens, like the ones my father and his brothers felled and cleared, digging and hauling out the stumps to plant grain, covered the hills. The memory brought to mind my father’s physical strength and resourcefulness in hard times. In summer when he had no income from teaching, we hired ourselves out as farm labourers and built houses to make some money—very little! I remember digging out basements and foundations with nothing more than a shovel!

Finding the remains of the ferry involved some sleuthing. Upon arriving in Vanderhoof we went straight to the O.K. Cafe in the Vanderhoof Community Museum for a bite to eat and to ask questions. One thing led to another and after lunch we went from place to place and person to person around town. People remembered the ferry and roughly where it crossed the river, and through contacts suggested by the waitress in the café, the receptionist of the museum, our chamber maid in the Hillview Motel, local historian Lilian Macintosh, a gruff employee of the Unified Feed Store who had sold land in Braeside, and a few serendipitous chance meetings, we followed false leads, went on wild goose chases, and came up with dead ends until, after much perseverance, we were able to identify the sites on either side of the river where the ferry had docked.

At one point we followed a lead to an impressive house and outbuildings with a lean-to for cattle on the shore below. The house sat above the Nechako with a commanding view of the fast-flowing, almost rushing, river. It occurred to me that had things worked out differently, some Suderman descendants too might be living in such a home overlooking the river.

It wasn’t until the second day, however, that we finally located the Engen side of the ferry. In my notes I wrote: “We continued down Engen Road to the end … the ferry site. We walked that last few steps to the water’s edge. It was a beautiful walk, the air fragrant with Indian paintbrush and sweet grass, wild lilies, daisies, and wild roses, and a little yellow flower; there were sighing breezes wafting through the very tall evergreens that shaded our trail, and a choir of birdsong radiated out of the trees, and butterflies, huge ambling butterflies! I could see why a little girl of 10 would remember the place with woder, [so] pristine and beautiful. I snapped a couple of pictures to record the view of the north shore of the Nechako where I assumed the Braeside ferry landing would be, as well as the Nechako itself.”

Shortly after, we discovered the Braeside moorings. We had dropped in on our waitress’s cousin, a Mrs. Lorna Ephrom, who gave us good directions. The road to the landing, overgrown towards the end, went down almost to the water and we parked and walked a good distance to the water’s edge where we ran into a Karen and Melvin Wiebe. Melvin worked as a gravel trucker at the gravel pit and knew exactly what we were looking for. He showed us the two concrete anchor moorings in the sand, with bent and protruding rusty threaded bolts, once used to anchor the line for the ferry. I now knew where I was in relation to the Suderman farm!

Mel also told us a driver had recently unearthed two rotted, ant-infested wood coffins at the gravel pit, and a third down the hill from it. The coffins carried no identification, unfortunately, and he said that graves of settlers and Indigenous peoples were often found, so there could be no assurance that these three had belonged to our family.

We left the site and almost immediately came across an abandoned old house on our left that we had missed walking down, with a large meadow that ran down the slope to the river. From descriptions I’d heard and photos I’d seen, I knew immediately that this must be the Suderman farm and the remnants of one of the buildings. It was a wonderful moment! We stood and contemplated the peaceful scene and the sad story it harboured. So much family history ran through my mind.

I was never able to track down a record of sale to the Sudermans to confirm the site. I tried Land Recording divisions in Burns Lake, the capital of the Nechako district, Vanderhoof, Prince George, and the BC Archives in Victoria but was unable to unearth a document for the sale. Nor, to my disappointment, did the Nechako Valley Historical Society or Vanderhoof Historical Society have any such record. However, I remain convinced that this was the Suderman farm and what remained of the homestead so hard won from the land.

War and Peace

The Nechako Valley surely was a Garden of Eden, but not for the Sudermans. Their pioneering effort had impoverished the family into the next generation and resulted in spiritual distress. Rather than helping them prosper, they believed God had punished them for attempting to evade the draft.

Vanderhoof’s failure presaged the end of four hundred years of Suderman belief in and practice of uncompromising passive resistance, anti-militarism, and rejection of governmental authority. The idea of participation in some wars in some form, as among other Mennonites, had taken hold among us starting with my father and me.

Nonetheless, I still believe that peace is always best. I have been involved in working for world peace for many years as a member of organizations like Citizens of the World and the World Federalists, and was one of the early promoters of the United Nations Declaration of Human Duties and Responsibilities. I believe human beings have responsibilities as well as rights, and one of our responsibilities is to seek peace.

I am among the last of those who have lived through many of the great upheavals of the twentieth century, and now in the twenty-first century remain rooted in the belief that a militaristic response to international conflicts is misguided, and that it is still possible to conceive of a peaceful world.

- Suderman (also Sudermann) was a relatively common surname in West Prussia (now part of Denmark and Germany) and in what is now Belgium when the Anabaptist movement began in 16th century Netherlands. In the old part of Antwerp, there is a short street called “Sudermanstraat.” According to a Flemish document unearthed and translated for me by a local archivist, the street was named after a Heinrich Suderman, a German who came to Antwerp in 1345 to bring presents to two cloisters, the Zwartzusters (Black Sisters) and the Cellebroeders (Brothers of Celle). For his generosity, a nearby street was named after him and while it has seen better days, the name still stands, as do the cloisters, though one is now a school and the other an office building. ↩︎

- Ernest N. Braun, “Why Emigrate?,” Preservings 34 (2014): 4-10; Hans Werner, “Something … we had not seen nor heard of: The Mennonite Delegation to Find Land in ‘America’,” Preservings 34 (2014): 11-20. In brief, the Mennonites who left Russia and chose Canada were concerned that their status as non-militaristic citizens, their Privilegium, granted under Catherine the Great, was to be rescinded. There is indication they were also land hungry. Similarly, those who left Prussia in the 18th century were restricted by the militaristic regime of Frederick II (“The Great”) in not being allowed to buy more land since they were legally exempt from military duty and military taxes. Before that, during the Spanish Inquisition in The Netherlands in the 16th century, the Mennonites had accepted land and religious freedom in Prussia. ↩︎

- Derek Suderman, “Peace Perspectives,” Mennonite Historical Society of Canada, 1998, www.mhsc.ca/index.php?content=http://www.mhsc.ca/mennos/tpeace.html; Ross W. Muir, “’Let nobody judge them,’” Canadian Mennonite, Oct. 23, 2013, www.canadianmennonite.org/articles/let-nobody-judge-them. ↩︎

- The area to which Catherine the Great invited the Mennonites was then known as New Russia, and by the Mennonites as South Russia. It is now Ukraine. For simplicity, the term Russia will be used in this article, as in Braun, “Why Emigrate?”. ↩︎

- Allan Labun, The Family Story of John and Susan Suderman, (Winnipeg: CP Printing, 2014), 67 (Allan is Anna Suderman’s son); Howard Dyck, “Tragedy in Vanderhoof,” Mennonite Historian 41, no. 3 (Sept. 2015): 4. ↩︎

- Peter Penner, No Longer at Arm’s Length: ME Church Planting in Canada (Winnipeg, MB: Kindred Press, 1987), 10-15 and 72-83; also cited in Peter Penner, “The Heinrich Voth Family: From Minnesota to Winkler to Vanderhoof,” Mennonite Historian 24, no. 4 (Dec. 1998): 1-2. ↩︎

- Penner, “The Heinrich Voth Family,” 1-2. ↩︎

- Penner, No Longer at Arms Length, 15, 79. ↩︎

- J.V. Neufeld, The Mennonite Settlement near Vanderhoof in the Nechako Valley British Columbia 1918, cited in Labun, The Family Story of John and Susan Suderman. ↩︎

- Labun, The Family Story of John and Susan Suderman, 65. ↩︎

- The Nature Guide to the Nechako River (Vanderhoof: District of Vanderhoof, 2013). ↩︎

- Labun, The Family Story of John and Susan Suderman, 69. ↩︎

- Ibid., 71. ↩︎

- J.V. Neufeld, “The Nechako Valley Settlement, 1918,” and the diaries of Peter Neufeld, cited in “Mennonite Settlement near Vanderhoof, B.C. in 1918,” Feb. 12, 2018, https://vanderhoofonline.com/mennonite-settlement-near-vanderhoof-bc-1918/. ↩︎

- Jake (1895–1945) organized educational trips in summer for his colleagues to places like the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. That he could have spent what little money we had on his family, rather than on some of his adventures, was a sore point with my mother and sisters. He was also a missionary spirit in Burwalde and not always appreciated for promoting his Mennonite Brethren views in his schools. Jake’s brother Henry (Harry) followed his sister Marie to California where she lived with her evangelist husband, Henry F. Klassen from Steinbach. Jake’s sister Margaret went to India as a missionary and spent over thirty years there as a leading force in public health. She trained nurses, pharmacists, and medical staff and evangelized in villages near the hospitals where she worked. ↩︎

- Janice Dickin, Patricia G. Bailey, and Erin James-abra, “Influenza (Flu),” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Sept. 29, 2009, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/influenza. ↩︎

- Glen R. Klassen and Kimberly Penner, “The 1918 Flu Epidemic,” Preservings 28 (2008): 24. Klassen and Penner are inclined to discount religious, cultural, and geographic factors for the higher rate of the flu among Mennonites and hypothesize that social or genetic factors may be responsible, but further research would be required to be sure. ↩︎

- Dyck, “Tragedy in Vanderhoof,” 2. For a moving account of the three deaths, see the letters of Peter and Helena Neufeld and Diedrich and Maria Dyck translated by Howard Dyck. In possession of Howard Dyck. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Conrad Stoesz, “Migration to Burns Lake, B.C., 1940,” Preservings 28 (2008): 29; Penner, No Longer at Arm’s Length, 15. ↩︎

- Patrick Morican, “Local World War 1 Stories” in War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy (Winnipeg: Manitoba Historical Society, 2014), 91-92, www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/features/warmemorials/stories.pdf. ↩︎

- Labun, The Family Story of John and Susan Suderman, 80. ↩︎

- For example: Randy Turner, “A Soldier Shunned: the horror of war, the conflict of faith, the Mennonite burden,” Winnipeg Free Press, Nov 9, 2013, www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/lestweforget/A-soldier-shunned-230552091.html; The Pacifist Who Went to War, directed by David Neufeld (2002; Ottawa: National Film Board of Canada), film; Vernon Toews, “I was a C.O. during World War II,” in Manitoba Mennonite Memories, 1874-1974, eds. Julius G. Toews and Lawrence Klippenstein (Winnipeg, MB: Mennonite Centennial Committee of Manitoba, 1974); Muir, “’Let nobody judge them’”; Peter Penner, “By Reason of Strength: Johann Warkentin, 1859-1948,” Mennonite Life (Dec.1978): 4-9. ↩︎