Klaas W. Brandt: Engineer, Surveyor, Metal Fabricator

Dan Dyck

A 136 km aqueduct. A hydro-electric power plant. The Ford Motor Company. A church and a school house. Steinbach’s first airplane. World War Two spy planes. These are just a few of the disparate threads that weave together the prolific professional life of Klaas W. Brandt (1876–1954), Steinbach area engineer of Kleine Gemeinde origins, land surveyor, and metal fabricator. He was a reserved, humble entrepreneur whose behind-the-scenes work is mostly invisible to residents of Manitoba today.

Part of a large family of nineteen siblings, Klaas was the first-born child of carpenter and wagon builder Heinrich R. Brandt (1838–1909) and Katharina Warkentin. Katharina was his second wife. (Heinrich had three wives over his lifetime). Heinrich and Katharina immigrated to Canada from the Borosenko colony in Russia, arriving onboard the S.S. Austrian in Quebec City on August 20, 1874.1

Klaas was independent of spirit and motivated to pursue his interests in a technical vocation. He ran away from his home, likely in the Blumenort area, as a teen.2 Not wanting to farm, he found a job in Steinbach.

In 1902, he wed Helena R. Friesen (1883–1946). For a short time, the couple farmed at Clearsprings, north of Steinbach. By 1913–1914, Klaas’ engineering interests led him to sell the farm to C. T. Loewen for the sum of $6,500.3 It was during this time that Klaas, with only a grade three education, all in the German language, studied engineering via correspondence from a university in Chicago.4 After selling the farm, the couple took up residence in the town of Steinbach, with three young children: Henry (1907), Katherine5(1910), and Elizabeth6 (1914). A fourth child, Elma, arrived in 1923.

Helena,7 a spirited and compassionate woman, has a story all her own, which includes independently operating a café in Steinbach, while Klaas owned and operated Steinbach Sheet Metal. This shop, consisting of both existing and added buildings, was located on the same lot as the café, on the north side of Main St. near Friesen Ave.

In writing about Brandt, one cannot ignore the Friesen family. Brandt’s father-in-law, Abraham S. Friesen (1848–1916), was a minister, an entrepreneur, and Steinbach’s first mayor. He owned much of the land at the intersection of Main St. and Friesen Ave., which was named after him. The intersection was an active social and business hub in the town, and the Brandt and Friesen families shared not only familial ties, but also business interests.

Water and Electricity Projects for Winnipeg

The booming city of Winnipeg had long been plagued by a lack of quality water. Mineral scale buildup in hard water from community wells was ruining everything from commercial heating boilers to tea kettles. Homemakers and domestic help required huge amounts of soap to properly suds wash water for clothing and dishes. Softer water, hauled from the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, led to more than one typhoid outbreak.8

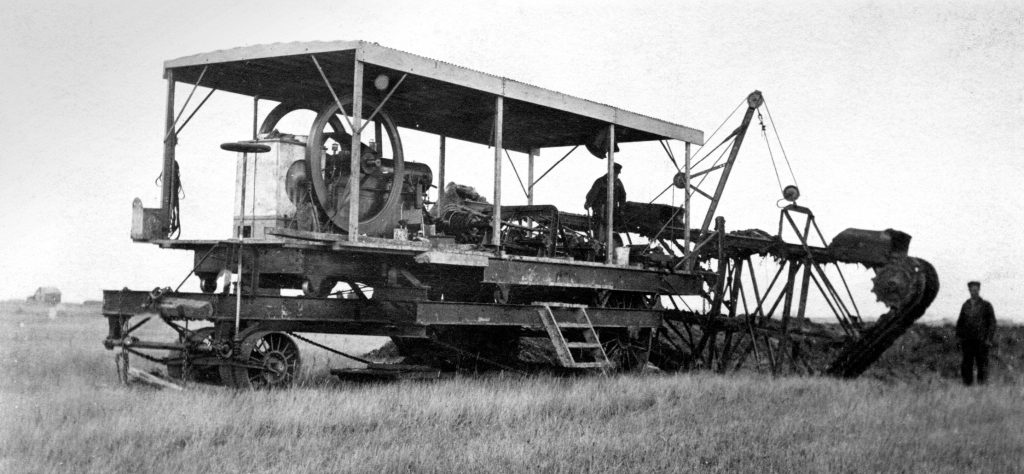

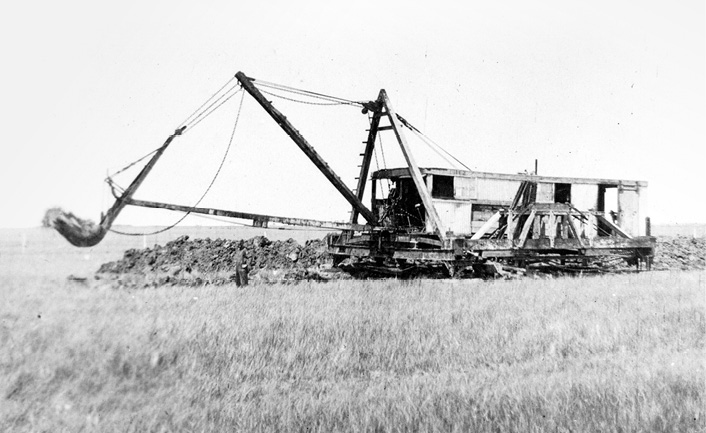

When the city announced it would build an aqueduct to move high quality water from Shoal Lake, on the Manitoba-Ontario boundary, to Winnipeg, Brandt was intrigued. He began designing a sixty-ton9 walking dredge for the project, together with his brother-in-law, Klaas R. Friesen,10 in 1914. Consultants and engineers from New York had designed a similar but much smaller scale aqueduct in that state. They planned a route for the aqueduct that would allow water to flow to Winnipeg purely by gravity. The Manitoba aqueduct would need to traverse all manner of terrain, and be piped underneath creeks and rivers. To follow the slope toward the city, the route would pass through swampy areas that would mire traditional excavation machines.

By means of winches and animated skid-like feet, Brandt’s dredge could be moved under power of an onboard gasoline fueled engine. Its wide and long feet could effectively float the machine on muskeg that would otherwise ensnare traditional excavation equipment. A large shovel dug a trench in which the concrete duct would be formed. The machine would then crawl ahead on its feet to dig out the next section. This process was repeated for a total of about 6.5 km of unstable, soft ground.

Brandt began his section of the route in 1916. It took four years to complete. The unit was expensive to build and operate.11 Though the work proved unprofitable, he gained valuable engineering experience.12 It was during these years that Brandt worked toward his engineering degree via correspondence. Brandt must have been a highly intelligent, eager learner. One can only imagine the math skills and English language learning he would have had to acquire with only a grade school education.

There are conflicting stories on what inspired Brandt to design and build the dredge. One source says the aqueduct captured Brandt’s imagination.13 Another indicates Brandt was commissioned by James Forestall of St. Pierre in 1912 to build a dredge. It was needed to dig canals and ditches for land drainage in the local municipality.14 One source says the dredge was bought back by Brandt and Friesen.

This is verified by a K. R. Friesen journal entry that indicates Forestall did not know how to operate the machine, and no longer wanted it.15 The journal goes on to describe ditch digging work performed by the Forestall machine in Heuboden and Oak Forest from 1912–13. The dredge built for the Shoal Lake aqueduct did not begin its work until 1916. One source states that construction of the Shoal Lake dredge took place from 1914–15.16 This puts the service date of the Shoal Lake dredge fully two years later than the Forestall dredge.

In photos, the Forestall dredge and the Shoal Lake dredge appear to be constructed quite differently. The Shoal Lake dredge appears to be larger in scale. It’s possible that components, such as the power source, of the Forestall dredge were repurposed for the Shoal Lake dredge. Could it be that the Forestall dredge continued its work of land drainage even as the Shoal Lake dredge was being designed and built? In any case, it is possible Brandt built two dredges.

The Shoal Lake aqueduct “… was not only one of the major engineering projects of its era… It was, and still is, one of the longest gravity-fed covered aqueducts built in the world since the early Romans pioneered aqueduct construction more than 2,000 years ago.”17 If there were two dredges, perhaps the high profile of the aqueduct made the Shoal Lake dredge the dominant memory – and story – while the Forestall dredge faded into the background.

Whatever the case, Klaas felt the Shoal Lake dredge was his biggest professional accomplishment, according to eldest grandson Dave Brandt, physics professor and retired president of George Fox University in Oregon. Dave recalls his grandfather shared stories of the dredge and working on the aqueduct. These recollections were often spurred by a photo of the machine that hung on his bedroom wall. In 2019, the aqueduct will have served Winnipeg without fail for one hundred years.

After Brandt’s work on the aqueduct was complete, he became a tool maker at the Great Falls power plant development on the Winnipeg River, twenty-four kilometres north of Lac du Bonnet. The project, begun in 1914, was halted due to the First World War and resumed in 1919. Little information is available on what Brandt’s work entailed on this project. He was an avid photographer, however, and in his collection are numerous images of the Great Falls plant at various stages of construction.

Surveying the Land

With the completion of the aqueduct and dam projects, Klaas Brandt found employment as a land surveyor for the Province of Manitoba around 1926. Field work took Klaas to the Central Plains region of Manitoba – McCreary, Plumas, Waldersee, and Glenella, to name a few places. With roads still in development and cars relatively primitive, he stayed for prolonged periods both in Winnipeg, where he rented a room, and north off Highway 5 where he often stayed at the Glenella Hotel (now named the Corona; the original building is still in use today).

In those days the hotel proprietors lived on the premises and provided full course meals for their guests in the large main floor dining room. A good recipe was never lost on Klaas, as he was accustomed to his wife Helena’s good cooking. Pickled beets and a somewhat hot mustard (later dubbed by Klaas’ family as “Brandt” mustard) came from the hotel kitchen and both recipes are still used by the Brandt family today.18

Since Klaas Brandt’s career kept him away from the family home for long periods of time, the family found other ways to interact. They often met in Portage la Prairie, the halfway point for both Klaas and his wife and children. Son Henry would drive the family in the Model T Ford and upon arrival they would enjoy a picnic lunch likely of ham sandwiches on Helena’s home baked brown bread accompanied quite possibly by “Brandt” mustard. Brandt also included his grandchildren in his work. From age ten to about fourteen, grandson Dave Brandt served as Klaas’ roadman on land surveys. Together, they surveyed many of the lots in present day Steinbach. Dave’s pay at the end of the day was always a Coca-Cola and chocolate bar when they got home, a treat the young boy always relished.

Klaas’ family equated engineering work with long absences so years later when Dave announced his own intention to become an engineer, his aunts expressed their dismay. The existence of different engineering disciplines was news to them!

Improving Ford Car Dealers

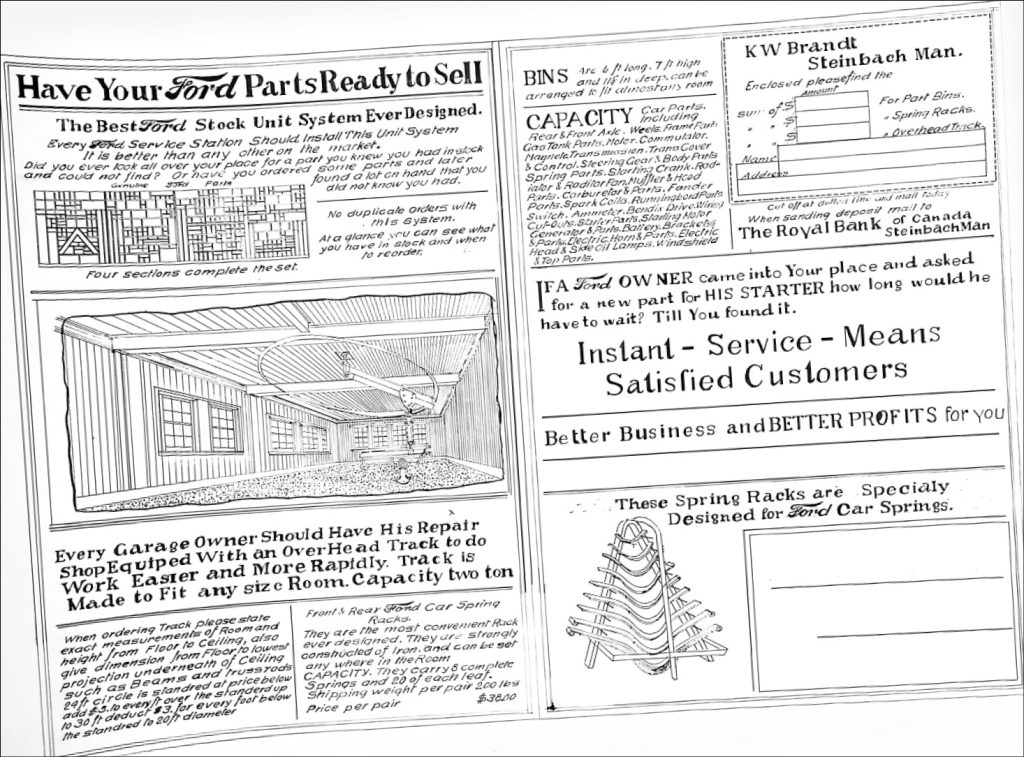

Brandt was always thinking about how to solve problems with engineering designs. In 1922, he developed plans to improve the car parts inventory and retrieval systems for Ford car dealers. He brainstormed ideas for racks, bins, and shelves customizable to any space designed to efficiently organize the wide array of oddly shaped parts that comprised a Ford automobile. These ideas became drawings such as an overhead track design that would ease the lifting and conveyance of heavy parts.

The drawings spawned a proposal, and then promotional materials. “If a Ford owner came into your place and asked for a new part for his starter, how long would he have to wait?” reads Brandt’s pitch. “Till you found it,” he answers his own question. “Instant service means satisfied customers” and “Better business and better profits” are other slogans that appear. The Ford brand is hand-drawn with the flourished script that still adorns the company’s cars today. Not only was Brandt a designer and engineer, he had a flair for marketing. We don’t know if his ideas ever found traction in Ford car dealerships, but it’s clear that Klaas W. Brandt aimed high. It would have been a significant business coup to supply a burgeoning car dealership network.

Given the close nature of the Brandt and Friesen families, likely Klaas’ inventory solution arose from dinnertime conversation. In 1914, J. R Friesen, Brandt’s brother-in-law, had opened the first Ford dealership in western Canada on the south side of Main St. near Friesen Ave. This was directly across the street from the Friesen Machine Shop. Both businesses are still in operation today as Fairway Ford and Friesen Machine Works, respectively.

From Land to Air

Official historical records are silent on Brandt’s role in building Steinbach’s first airplane. But detailed drawings of the plane, including the fitting of a Ford engine to the aircraft, are in the donated collection of Brandt’s documents at the Mennonite Heritage Archives.

Like many adventurers in the early days of flight, brothers-in-law Frank Sawatzky and William Wiebe couldn’t resist seeing the land from the air. The young duo was excited by an advertisement selling detailed plans to build a Pietenpol Air Camper in a twenty-five-cent magazine called Popular Mechanics and Inventions.19 Unable to afford the detailed plans, the pair used a magnifying glass to surmise and decipher measurements from photos of the limited views in the magazine. In 1932, high resolution printing of magazines was still decades away. Many calculations must have filled in gaps the advertisement did not provide. With Klaas’ help, they drew up their own plans – quite a feat of ‘imagineering.’

To turn the paper plans into a real airplane required funds. Sawatzky and Wiebe approached their mutual father-in-law, Ford dealer J. R. Friesen. The plans called for a Ford Model A engine. The pair convinced J.R. that using such an engine would be good advertising for his cars. “If you could tell your customers that this engine will also fly an airplane, you’re going to be ahead of your competitors,” Sawatzky told Friesen.20 J. R. was sold on the idea.

They began building the Pietenpol Air Camper in January 1932. It was originally conceived by Bernard H. Pietenpol, a designer of homebuilt aircraft, in Cherry Grove, Minnesota. The maiden flight attempt of the Sawatzky and Wiebe version was unsuccessful. The aircraft was heavier than expected. Sawatzky’s inexperienced piloting skills were overconfident. A stony pasture serving as an air strip tripped up the wheels and wrecked the propeller on take-off. A new propeller was soon fashioned from local hardwood. Skeptical Steinbach residents gathered to see the second attempt, which was successful, just over three months after construction began. This time, an experienced pilot, Frank Brown from Winnipeg, was in the cockpit.21 Sawatzky continued to play a key role in the construction of two more airplanes, creating enormous excitement in the community. Flying exhibitions from 1932–34 drew huge crowds.22

In addition to being blood relations with the Frank Sawatzky family (Sawatzky’s wife, Anne Friesen, was a niece to Klaas’s wife, Helena), they were also great family friends. “I suspect that Grandpa and Frank Sawatzky talked about airplanes a lot,” said grandson Dave. Clearly Brandt played an influential role in the project, as evidenced by the drawings in his collection. But being a reserved and humble man, his role in building Steinbach’s first aircraft remained behind the scenes.

Another of Brandt’s involvement with aircraft requires some context. By the early 1930s Brandt and his family had grown weary of work that required long term absences. By now he had considerable engineering and business experience and in 1935 he decided to open Steinbach Sheet Metal in partnership with his son, Henry (Dave Brandt’s father). Originally the shop specialized in tinsmith and heating duct manufacture and roofing projects. Over the years it outgrew its name and expanded to include a machine shop and foundry.

Henry’s more extroverted personality was suited to sales. Klaas’ reserved nature, innovative ideas, and attention to precision and details fulfilled the technical needs. The two made a fine combination.23 This arrangement finally allowed Klaas to work near home and family.

The shop became ideally suited to manufacture a wide variety of components for diverse applications. With sugar rationed, honey taps for beekeepers was a popular item during the war years, as honey became a readily available sweetener.24 The manufacture of honey taps kicked off the machine shop and foundry expansion. The foundry began as an outdoor operation in the backyard during the early 1940s, operating only in the warm season. Soon, Brandt was manufacturing aluminum components for honey extractors and other honey processing equipment.

It was during the post-World War Two era that interviewees Dave Brandt and John Henry Friesen, Dave’s long-time friend and second cousin, recalled Brandt’s creative re-purposing of surplus World War Two spy airplanes. With the end of the war decommissioned aircraft of different designs could be found at air bases around Manitoba, including at Gimli and Rivers, Manitoba. Klaas travelled to inspect many of them, and found they were all priced the same. But he determined that the Lysander airplanes in Rivers, with their 890 horsepower aluminum engines, were the best value for the money because they contained the most metal.

The Lysander was designed to fly low, slow, and take off in just seventy feet on improvised airstrips. It was used to pick up or deliver spies in enemy territory.25When the Second World War ended in 1945, the government of Canada began dispersing surplus military goods, including about twenty-five Lysander airplanes located in Brandon, Manitoba.

But how to move an aircraft with a fifty-foot wing span from Brandon to Steinbach? Brandt and his associates managed to fold up the wings and towed the individual planes by road, late at night – mostly between two o’clock and five o’clock in the morning – when traffic was minimal.

The aluminum was melted down in the foundry, then re-casted and machined into new products. About twenty-seven planes were purchased.26 The planes were stored in the Brandt’s family garden, much to the dismay of Helena, and provided aluminum for many years. “They were marvelous toys for a ten-year-old,” remembered Dave. “We climbed into the cockpits and were flying all over Germany.” John Henry Friesen, playmate and second cousin to Dave, recalls finding a leather holster for a German handgun in one of the plane cockpits. It eventually disappeared, possibly confiscated by elders. Recycling and transforming weapons of war into life-giving tools is certainly not an idea limited to the current generation.

As the war ended, so did sugar rationing. The market for honey making equipment dropped off the map. But the end of the war also meant that rubber, previously diverted to the war effort, once again became available. Abe Penner, founder of today’s Steinbach Chrysler Dodge car dealership, together with brother John, recognized an opportunity to outfit tractor and farm implement wheels from steel to rubber. They designed a kit that contained everything needed for various brands of farm machinery and sold it to farmers. This required the custom manufacture of cast iron hubs machined to adapt to existing axles, a job ideally suited to Brandt’s metal shop. The work led to several years of the metal shop operating for twenty-four hours, six-days-a-week.

Though the steel wheel to rubber tire transition market eventually dried up, the experience led to other work. The shop began fabricating a wide variety of aluminum and gray cast iron products contracted by other companies. One of those contractors was Brandt manufacturing in Regina (no relation),27 a maker of grain augers and later, other farm equipment. The Brandt family of Steinbach manufactured “pulleys, gears … and round parts – anything that rolled on an axle,” recalled Dave. The Brandt-Brandt contracts developed into a strong relationship that went on for five years.

By this time the product line had changed so much that the father-son duo decided to change its name to Brandt Manufacturing. Just after the war, the heating and roofing portion of the business had become tertiary. It was sold to Barkman Hardware, a retail and heating and plumbing operation and predecessor of what is Barkman Concrete today. But before the business could change its name, Klaas passed away. Responding to these circumstance, his son Henry made the decision to close down the business and follow his passion of full-time pastoral ministry, which led the younger generation of this family to a church in Mountain Lake, Minnesota.

Life, Faith, Character

Small in stature, disciplined, and a perfectionist by nature, Brandt is remembered as a hard-working man of few words.28 He taught grandson Dave how to run a metal lathe at age twelve. Dave worked in his grandfather’s shop one summer. Klaas had high expectations of his workers. He didn’t accept Dave’s “good enough” work on the lathe.

As the boss of the machine shop, Brandt was not one to offer mere opinions. “Grandpa Brandt didn’t speak a lot, and didn’t speak very loud, but he was very precise,” said Dave. Everyone had to listen closely when instructions were given.

He was also a very serious person. “I don’t remember him telling jokes, or laughing much,” said Dave. “He didn’t talk much about his faith, but he took those commitments very seriously, if quietly. When he committed to a person or an organization, it was with his whole being.”

While Klaas was baptized as a young adult in the Kleine Gemeinde church around 1919, the family joined the Bruderthaler church in Steinbach, attracted by its Sunday school and choir. Later, Klaas made architectural drawings for the new Bruderthaler church. Initial drawings are identified in his collection as “Preliminary Plan of Bruderthaler Church Steinbach” and are dated February 25, 1928. Blueprints for a heating duct plan identified as “Def. Menn. Brethren” [Defenseless Mennonite Brethren] in Steinbach are dated November 5, 1930.

Later, when the church was raised to place a basement underneath, it must have received other alterations, such as differently shaped windows, and a corner belfry.29 Dave Brandt estimates the church was completed in the late 1930s. Other architectural plans in the collection include drawings for the Kornelsen School, residential building (including a home for a local doctor), K. Reimer and Sons Store (dated Aug. 26, 1923), the Giroux Hall (dated May 27, 1921), and a site plan for the Steinbach Cemetery (located at Sec. 27-6-6E on the drawing).

Klaas’ son and Dave’s father, Henry, was part of a founding group that established an Evangelical Mennonite Brethren congregation in Winnipeg. Henry was pastor of the Christian Fellowship Chapel for a number of years in the 1940s, commuting from Steinbach to Winnipeg with the help of donated fuel stamps from friends and supporters.30The church remains in existence today and is located 465 Osborne Street in Winnipeg.

Dave recalls receiving a lesson in behaviour from his grandfather, for his first communion service. Baptized at age thirteen, Dave needed to prepare for his first communion. These were special services on a Sunday afternoon. Dave received clear instructions to have a clean white handkerchief to hold the bread until all were served and were instructed to eat together. “He made very sure that his oldest grandson would do it right,” said Dave. In Klaas W. Brandt’s world, precision and accuracy mattered in all things. Whether in design engineering, manufacturing, personal health, or spiritual life, Klaas Brandt’s exacting nature defined his character and his life.31

- www.grandmaonline.org ↩︎

- Phone conversation with Dave Brandt, Oct. 23, 2018. ↩︎

- Hilton Friesen and Ralph Friesen, Abraham S. Friesen Steinbach Pioneer (Winnipeg, Hilt Friesen, 2004). The date of sale conflicts with a reference to the fall of 1910 found on page 633 in Ralph Friesen, Between Earth and Sky Steinbach the First Fifty Years (Steinbach, MB: Derksen Printers, 2009). ↩︎

- Notes from a conversation between Arlene Rempel and Conrad Stoesz, Archivist, Mennonite Heritage Archives, Dec., 2017. No record of his enrollment exists at the University of Chicago, as per investigation by Stoesz, who surmises Brandt may have studied via another university in Chicago. Grandson Dave Brandt says Klaas may have had a grade six education. ↩︎

- Spelled “Katherine” here as per family preference. The Grandma’s Window online database spells it “Catherine.” ↩︎

- Spelled “Elizabeth” as per family preference here. The Grandma’s Window online database spells it “Elisabeth.” ↩︎

- Helena’s story is documented in Friesen and Friesen, Abraham S. Friesen Steinbach Pioneer, 268–271. ↩︎

- Adele Perry, Aqueduct Colonialism, Resources, and the Histories We Remember (Winnipeg: ARP books, 2016), 39. ↩︎

- Friesen, Between Earth and Sky, 337. ↩︎

- Carillon News, March 13, 1953, as cited in Abraham S. Friesen Steinbach Pioneer, 269. ↩︎

- Phone conversation with Dave Brandt, Jan. 11, 2019. ↩︎

- Friesen and Friesen, Abraham S. Friesen Steinbach Pioneer, 269. We don’t know why the project was unprofitable. ↩︎

- Carillon News, March 13, 1953, as cited in Friesen and Friesen, Abraham S. Friesen Steinbach Pioneer, 269. ↩︎

- Friesen, Between Earth and Sky, 337. ↩︎

- Email from Ralph Friesen, Dec. 17, 2018. ↩︎

- Carillon News, March 13, 1953. ↩︎

- Rod McRae, the city’s commissioner of works and operations in a seventy-fifth anniversary article on the aqueduct published in the Winnipeg Real Estate News on April 15, 1994, http://www.winnipegrealestatenews.com/Resources/Article/?sysid=936. ↩︎

- In 1990 Klaas’s youngest granddaughter accepted a teaching position in Glenella. One of the teachers on staff at the school, a close relative of the long since deceased hotel owners, was interested to hear the history of their family’s good cooking and asked for copies of the long-lost recipes. ↩︎

- Ralph Friesen, “Entrepreneurial Legacy of A. S. Friesen,” Preservings, 9 (Dec. 1996): 74. ↩︎

- “Magazine Prints Plans, Steinbach Pair Builds Airplane,” Altitude (Spring 2016), reprinted online May 15, 2016, http://royalaviationmuseum.com/article-magazine-prints-plans-steinbach-pair-builds-airplane/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Wm. J. Friesen, Letter to the Editor, Preservings 19 (Dec. 2001): 62. ↩︎

- Phone conversation with Dave Brandt, Oct. 23, 2018. ↩︎

- Phone conversation with Dave Brandt, Jan. 11, 2019. ↩︎

- Phone conversation with John Henry Friesen, Oct. 13, 2018. ↩︎

- Phone conversation with Dave Brandt, Oct. 23, 2018. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Phone conversation with Arlene Rempel, Oct. 19, 2018. He was always very careful about his weight. In his adult life he developed what was probably Type 2 diabetes, which he controlled with a strictly self-disciplined diet. Phone conversation with Dave Brandt, Oct. 23, 2018. ↩︎

- A photo of the church taken in winter appears in God Works Through Us… (Steinbach: Evangelical Mennonite Brethren Church, 1972). Its caption reads, “Church as it looked from 1938–1954. By this time, the fence around the church has disappeared, concrete steps spanning almost the entire front of the church have been installed, and a utility pole appears directly in front of the building.” ↩︎

- The current church web site at lists Henry Brandt as pastor from 1949 to 1950. Son Dave Brandt estimates that his father’s pastoral work in this congregation began as early as 1942/43, ending in 1950. Phone conversation with Dave Brandt, Jan. 11, 2019. ↩︎

- Many thanks to family members Dave Brandt, Arlene Rempel, Ralph Friesen, and John Henry Friesen for generously sharing their time, being first readers, and offering correctives on early drafts. Ralph Friesen’s books on local Mennonite history were invaluable. Thanks to Conrad Stoesz, Archivist at the Mennonite Heritage Archives, for assistance during repeated visits. The Winnipeg Public Library provided useful books on the history of the Shoal Lake Aqueduct and the Greater Winnipeg Waterworks Railway. Sarah Ramsden at the City of Winnipeg Archives was most helpful in retrieving photos and documents related to the construction of the Shoal Lake aqueduct. ↩︎