The Early Life of Martin B. Fast

Katherine Peters Yamada

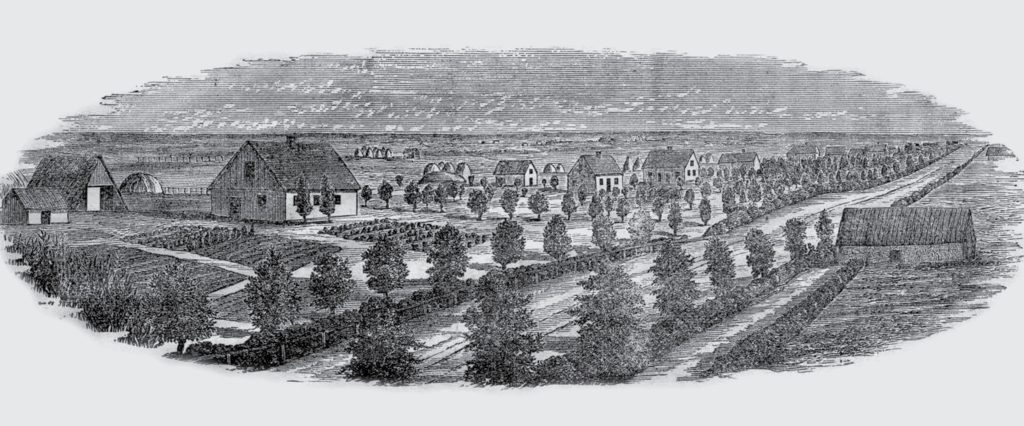

Martin Fast’s Mennonite forebears left their Prussian homeland in the early 1800s in response to an invitation from Russia’s Tsarina Catherine II, who sought experienced farmers to settle new lands recently wrested from Turkey. Both of Fast’s ancestral families settled in a Mennonite colony, Molotschna, established in 1804 in South Russia (present-day Ukraine).

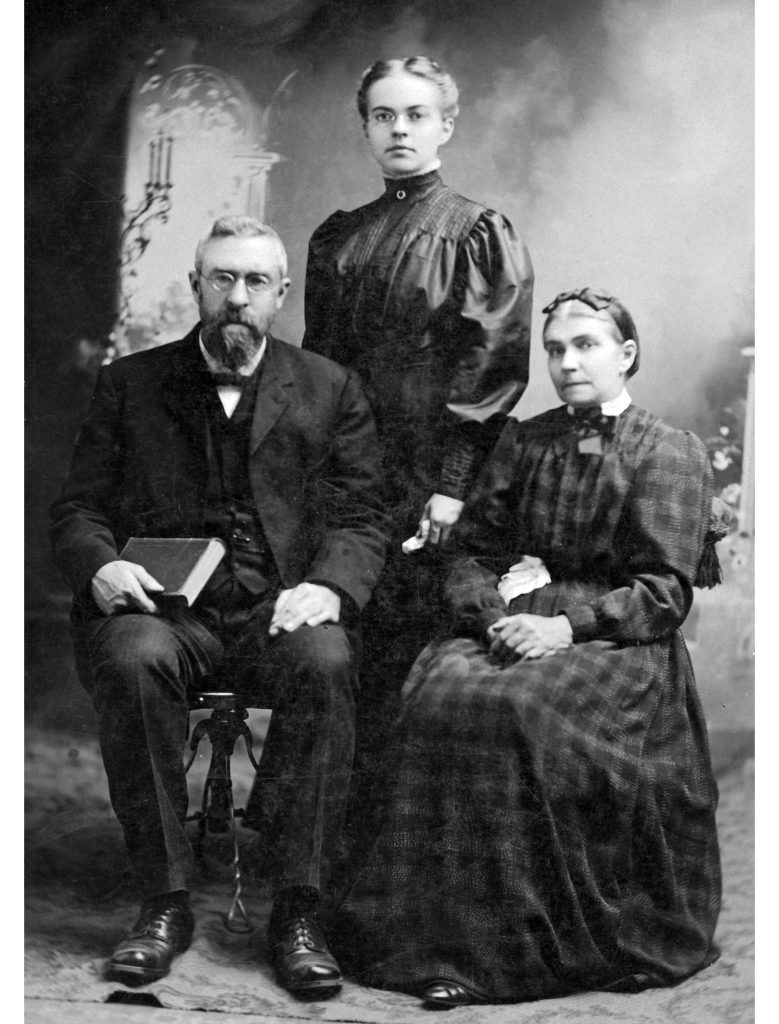

His maternal grandfather, Martin J. Barkman, was a prosperous farmer in Rückenau, one of the Molotschna villages. He was a staunch member of the Kleine Gemeinde, which encouraged nonconformity, humility, and church discipline while discouraging higher education and mission outreach.1

Fast’s paternal line included preachers, teachers, and writers. His grandfather Bernhard Fast served as a Kleine Gemeinde minister for a time and taught school in Rosenort, also in the Molotschna colony. At some point, he and his wife, Justina Isaak Fast, joined the larger Mennonite Church in the nearby village of Ohrloff and raised their son, Peter, in that church.

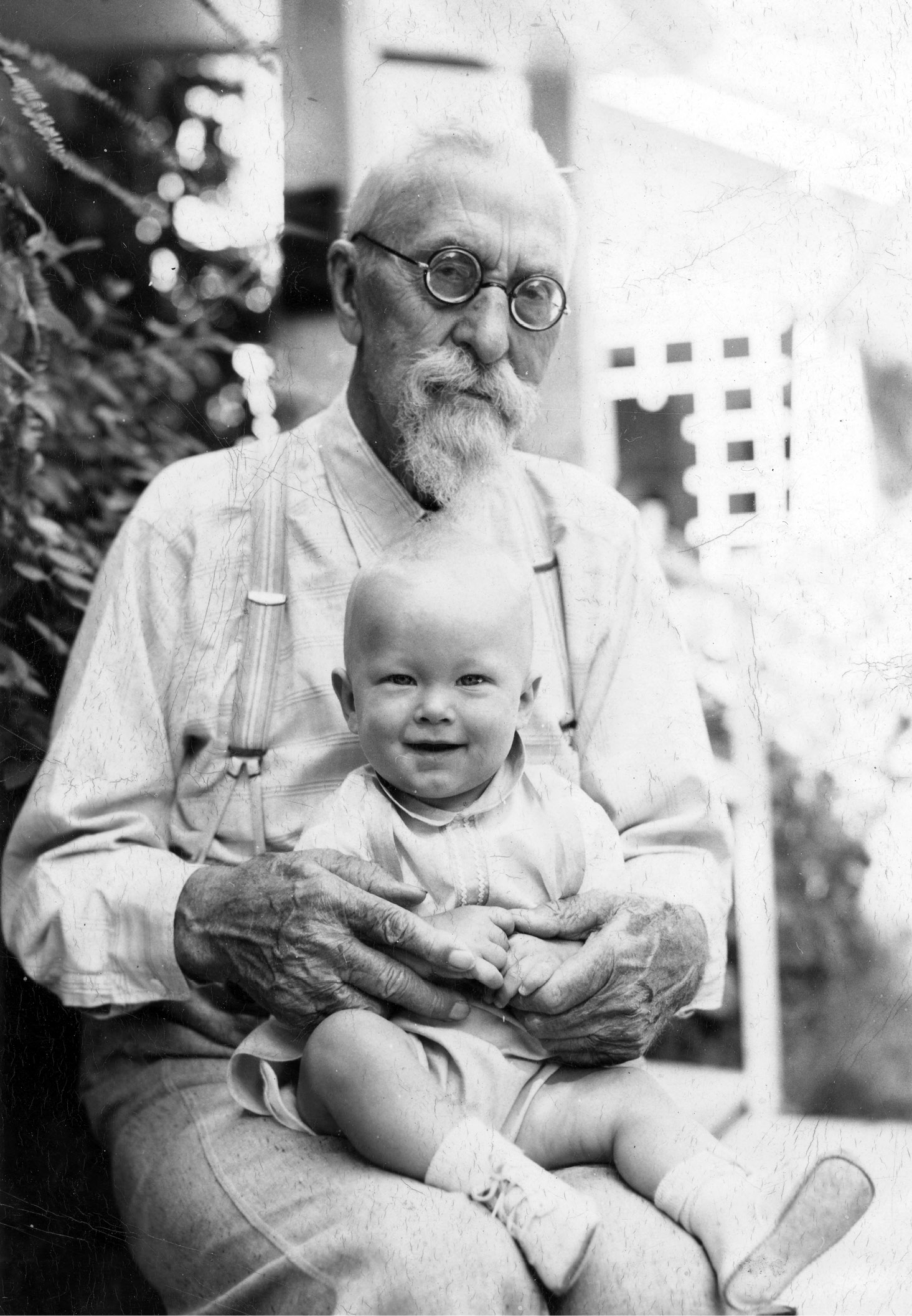

Fast was born in 1857 to Peter and Aganetha Barkman Fast in the small Molotschna village of Tiegerweide. His father, Peter, was an Anwohner (landless person) who mediated issues between the farmers and the landless, thus gaining the title of “Anwohner Mayor.”2 He supported his family as a miller before eventually purchasing a farm.

Two Influential Teachers

Young Fast entered Tiegerweide’s village school before he was six. There he learned to read, write, and calculate, using only a primer and the Bible. He had five different teachers in the course of six years and was greatly impacted by two of them. One of his first teachers, named Heidebrecht, told his students of a local widow who needed help. He encouraged his students to support her with a donation. As the six-year-old walked home from school that afternoon in 1863, he debated as to whether he should give the widow a copper coin from his “wish money” or a silver coin received as a Christmas gift. He decided on the silver coin, but when he told his mother, she discouraged him, concerned that he might later regret it. Nevertheless, the next morning, he took the silver coin to school.

Years later, in 1880, his generosity was rewarded. By then, his family had left Russia and relocated to Nebraska and Fast, in his early twenties, was preparing for his first communion in the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren (KMB) Church. He and several others had traveled to a small town near Gnadenau, Kansas for their testing. At the end of the evening, Fast discovered his group had inadvertently continued on without him. A fellow student, realizing what had happened, invited Fast to his family’s home for night. The next morning, Fast discovered that his hostess was that very same widow to whom he had given the silver coin. In his 1935 autobiography, he wrote, “I have often experienced how the Lord makes note of everything and often what we do for the benefit of our fellow human beings produces 100% interest.”3

In contrast to the generosity Fast learned from Heidebrecht in the Tiegerweide schoolroom, he suffered greatly under another teacher in that same school. This teacher frequently spent the evening in the local tavern and was not totally sober the next morning; he smoked his pipe and scolded the students, calling them “blockheads” and “dumb sheep.” One day, young Fast was seated next to a disruptive student. Thinking it was Fast, the teacher hit him over the head with a “big volume of Bible stories.” Seriously injured, Fast, not yet a teenager, was confined to bed for an extended period. The village mayor sent the teacher to apologize, but Fast reflected in 1935 that he had had great difficulty in forgiving the teacher. As an adult, he had referred to 1 Peter 2:23 for guidance: to act like Jesus, who “when he was reviled, reviled not again; when he suffered, he threatened not; but committed himself to him that judgeth righteously.”4

Fast had been an excellent student and was at the head of the class for a time. But after his injury and lengthy recovery, he did not return to that school. His family later moved, eventually settling in Rückenau, where he enrolled in the local school. When the term ended, he was fourteen and no longer of school age.

Youthful Desire to Be a Missionary

In his youth, Fast desired to be a missionary to a foreign country; but his desire was thwarted by his mother’s family’s strong feelings against mission work. From an early age Fast read not only the Bible, but also, despite the Kleine Gemeinde’s teachings, any books or stories that came his way. He was greatly disturbed by descriptions of “the sins of the slaveholders,” possibly referring to the highly popular book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852 and later widely translated. Several early editions included an introduction by a British minister noted for his abolitionist views.5 Reading about the plight of the slaves moved Fast both to sympathy and anger, which ignited a desire within him to become a missionary.

One Sunday evening, when he was in his very early teens, Fast was alone in his family’s Rückenau home. He sat close to the brick oven, heating it up slowly by filling it with straw, an hour-long task which had to be done on a regular basis. After finishing his schoolwork and studying his catechism, he decided to practice his preaching. He directed his sermon to the “imaginary heathen to whom I wanted later to be a missionary.” Speaking loudly, he didn’t notice that someone had come into the house. (It was customary in those days to enter without knocking.) His visitor was the local schoolteacher, Abram Isaak, who paused to listen to Fast preach before announcing himself.

When Fast traveled back to his South Russia homeland in 1908, he visited his former schoolteacher, who reminded Fast of that evening when he had preached to the imaginary heathen. The two men spoke of Fast’s youthful longing to be a missionary. But, it seems, Fast’s strong Barkman family, including his dear mother, had not encouraged this desire. Some years before, two of Aganetha’s brothers, along with many other Kleine Gemeinde, had left the Molotschna colony and resettled near Borosenko, where they hoped to strictly follow the teachings of their church. Fast’s mother evidently shared her brothers’ views, which discouraged higher education and mission outreach. As Fast noted, in the strong Barkman family “mission [was] a foreign word.”6

Many years later, his mother withdrew her objections to his youthful desire. On her deathbed in Jansen, Nebraska in 1899, she encouraged her son to be like Jesse Engel of the River Brethren who had “suppressed the spirit both directly and indirectly” before going to Africa as a missionary at age sixty-two.7 By the time his mother told him this, Fast was married in his early forties and the Lord had shown him “a different path.” He had joined a new foreign missions program, initiated in 1898 by six KMB congregations.8

To the United States

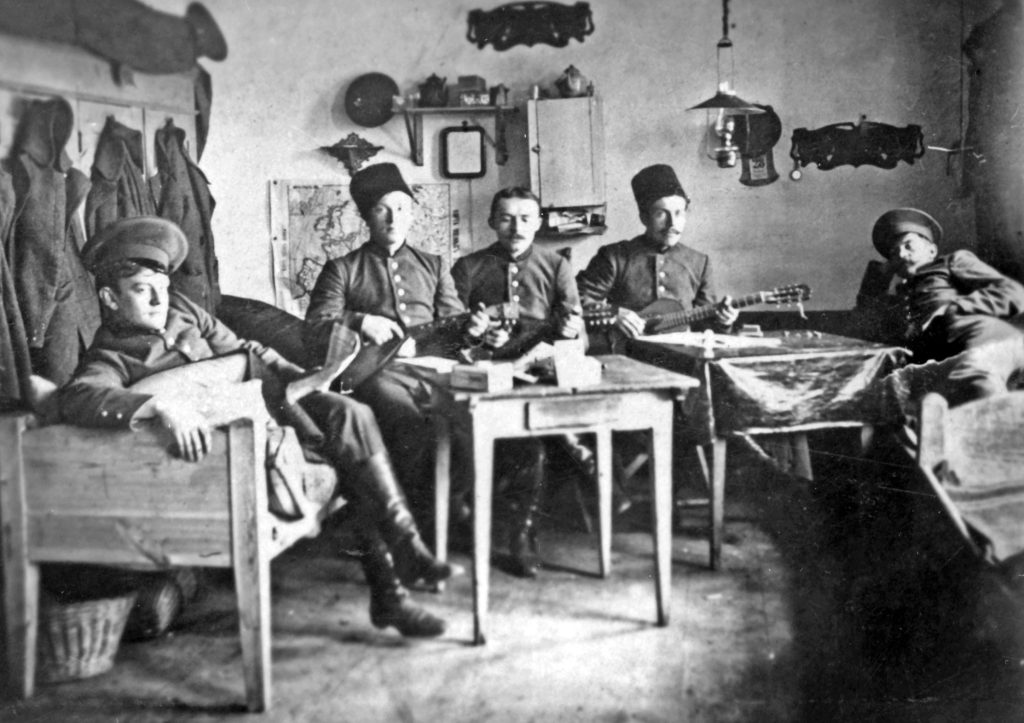

There were “great and many-sided upheavals all over the world,” as Fast was growing up in the Molotschna colony.9 The American Civil War had freed the slaves and Alexander II had eliminated serfdom in Russia. But the Russian government also introduced compulsory military service, thus rescinding the exemption given to Mennonites. They had ten years to decide whether to accept alternative military service or leave the country.

His father, Peter, agonized over the choice of staying on the farm they had finally been able to purchase or of joining the exodus to North America. If they stayed, Fast, then nineteen, would be forced to serve his country, either in the military or in the alternative forestry service. If they left, they faced huge financial losses and the great unknown of starting over in a foreign land. Eventually, Peter decided for the latter and in 1877 was elected to help lead one hundred families to their new home in Jansen, Nebraska.

In 1880 men from the KMB Church in Kansas came to Jansen. The KMB, established in Russia in 1869, was very conservative in its teachings, but encouraged evangelism outreach and mission programs.10 Fast became convinced that their teachings were biblical. After passing the testing in Gnadenau, Kansas, he was baptized into the church, along with others. His father, Peter, together with Peter Thiessen, helped form a new KMB Church in Jansen and Fast taught Sunday School.

Fast also applied for citizenship. He spread his wings by leaving home to work on the railroad, but then returned, perhaps to court Thiessen’s daughter, a young woman named Elisabeth. He had noticed her at a Kleine Gemeinde service soon after they arrived in Jansen. But his family was poor and when he learned that her parents were wealthy, he was discouraged about his chances of winning her hand.

Fast knew he needed a steady income in order to marry. He had been a good student back in Tiegerweide and was at the head of his class for a time. He could read and write well and was fluent in Russian. He knew he could teach. He applied for a position as teacher in the village of Rosenort, just north of Jansen. He also became a correspondent for J. F. Funk’s new Die Mennonitische Rundschau. 11

Funk established the Rundschau for the Mennonites from Russia who were living in North America by 1880. He later added a semi-monthly edition “for readers in Europe and Asia,” to keep them in contact with those who had come to North America. The subscription price was given as fifty cents, three marks, or one ruble, suggesting that it was sent to North America, Germany, and Russia.12

Fast described the Rundschau as a “friendship leaflet.”13 More recently, Conrad Stoesz, archivist at the Mennonite Heritage Archives in Winnipeg, Manitoba, remarked: “It was the Facebook of one hundred years ago.’’14 In any case, the Rundschau was a popular way for Russian Mennonites to keep informed about their fellow Mennonites.

One of Fast’s first submissions, on August 1, 1881, describing Mennonite settlements in Nebraska, appeared on page one of the popular publication. Further contributions, under the heading: “Aus Mennonitischen Kreisen,” (roughly translated as “From Mennonite Circles”) were also published on page one. This column, interspersed with his reports on conferences and trips to other states (along with poetry and hymns), appeared frequently for many years.

A year after becoming a Rundschau correspondent, Fast met with George Cross, editor of the local English-language newspaper, the Fairbury Gazette, and became a correspondent for that publication as well. “I learned a lot at this job,” Fast wrote, referring to the skills he gained in writing and speaking English.15

Fast still nurtured his youthful desire to be a missionary and his involvement with the KMB Church reawakened that desire. Meanwhile, his relationship with Elisabeth deepened as they encountered each other at Sunday worship services and Wednesday night prayer meetings at the KMB Church. When he first proposed marriage, he told Elisabeth of his missionary goals. She, in turn, said she wasn’t ready to leave her family. A year later, when Fast again proposed, she accepted. But this time, it was her father, Peter Thiessen, who delayed their marriage. He had planned a trip to Russia to visit relatives and asked the couple to wait until his return. After their 1884 wedding, they moved to a small property near Jansen and Fast tried farming, while also teaching German in the local school. But times were difficult and they lost the farm.

Becoming an Editor

In December 1903, after serving as a correspondent for Die Mennonitische Rundschau for more than twenty-two years, he was hired as the editor, which set him on the path that eventually led to his Siberian relief mission. When Fast was hired, he was concerned about his writing skills, but he learned quickly as he edited letters sent by correspondents from Mennonite communities throughout North America, Europe, and Russia. “Thanks to the Lord,” he later wrote, “most of the readers and I learned to understand each other.”16

He also wrote editorials. In one such editorial, in July 1904, he wrote of the one hundredth anniversary of the Molotschna colony, founded in 1804 by families from the Vistula Delta.17 One of his most frequent editorial topics, perhaps foreshadowing his own future efforts, was disaster relief in places ranging from Kansas to Armenia, China, India and, most especially, Russia. The Rundschau index references many Russia-focused articles, reflecting the love for his homeland that led Fast to his 1908 and 1919 trips.

As editor, he also received a steady stream of letters and appeals for help from Mennonites still in Russia. In 1906, Fast sent a contribution to one of those families. Then more appeals arrived. He published them in columns such as “Erhalten und Abgeschickt” (“Received and Sent”) and “Erhalten für Nothleidende in Russland” (“Received for the Needy in Russia”).18 More readers sent contributions for their Russian brethren.

Tour of His Homeland

In 1908, Fast embarked on a visit to the Mennonite colonies in South Russia. Leaving Elkhart in early May, he carried with him messages and packages to deliver and commissions (such as settling inheritances) to perform. He toured many of the Molotschna villages, revisited his boyhood haunts, reunited with friends and relatives, and spoke in church services.

He visited schools and orphanages and one of the forestry service projects set up by the Russian government in the late 1870s as an alternative to the military service which had impelled so many, including his own family, to leave in 1877. He also explored Mennonite villages in the Crimea, the Chortitza colony, and the nearby daughter colony of Memrik.

Everywhere, he visited with community and religious leaders, many of whom he had never before met. They knew of each other only through his position as editor of the Rundschau. He was informed of conditions in the new Mennonite settlements in Siberia, established after the Trans-Siberian Railway was completed. In 1906, seeking settlers for the vast territories now easily accessible by rail, the government made attractive land offers. Many South Russian Mennonites responded, establishing communities near Omsk and beyond.19

His trip took place during a time of transition for the Rundschau, which, along with Funk’s other publications, had been purchased by Mennonite Publishing House in Scottdale, Pennsylvania. Returning to Elkhart in early August, Fast had only a few days to bid farewell to friends and family before boarding a train to Scottdale.

His trip reports, first published in the Rundschau, were later compiled into a book, “Reisebericht und kurze Geschichte der Mennoniten,’’ published in 1909. Sometime later, he left on a tour of the Midwest, attending conferences and delivering the results of the commissions he had been given. Fast continued writing editorials on disaster relief in Russia and he continued soliciting and acknowledging donations.20

Fast served as editor of the Rundschau until October 1910, when an undisclosed health problem forced him to seek a replacement. He was loath to leave. Readership had increased under his leadership and he and his family had felt very much at home in both the Elkhart and Scottdale communities. After he announced in an editorial that he would have to give up the work that he loved so much, he received more than two hundred letters asking him to stay.21

Move to Reedley, California

Within a few weeks, Fast and his family moved to Reedley, California, near where his two sisters and many of his wife’s siblings had settled. He recovered quickly and joined the newly formed Zion KMB Church, the only KMB congregation in California. He and Elisabeth were founding members of the church, established in March 1911, and he served on the first ministerial staff. He may have been ordained during this time.22

While immersing himself into life amongst his immediate family, Fast was kept informed of happenings in Russia and on the looming conflict in Europe. Germany’s declaration of war against Russia in mid-1914 sent shock waves throughout the Mennonite world in Europe, Russia and North America. The disastrous consequences of the Russian Revolution and the ensuing Civil War across his homeland reawakened Fast’s youthful desire to be a missionary and inspired him to respond.

This is the first part of a two-part series by Katherine Peters Yamada on the life of Martin B. Fast. For Part II, see Preservings, issue 40.

- Harold S. Bender, “Kleine Gemeinde,” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online [hereafter GAMEO], 1956, http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Kleine_Gemeinde&oldid=145580, accesssed 9 Feb. 2019. ↩︎

- M. B. Fast, “Mitteilungen von etlichen der Grossen unter den Mennoniten in Russland und in Amerika. Beobachtungen und Erinnerungen von Jefferson Co. Dann noch von meinen vielseitigen Erfahrungen aus der frühen Jugend bis jetzt,” [hereafter “Mitteilungen”] trans. George Reimer, in Wahrheitsfreund (Inman, KS: Krimmer Mennonite Publishing Committee, 1935), 63–69. ↩︎

- Fast, “Mitteilungen,” 51–63. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 25 Feb. 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncle_Tom%27s_Cabin, accessed 26 Feb. 2019. ↩︎

- Fast, “Mitteilungen,” 51–63. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- P. J. B. Reimer, “The Sesquicentennial Jubilee of the Evangelical Mennonite Conference 1812 – 1962,” in The Sesquicentenial Jubilee: Evangelical Mennonite Conference 1812–1962 (Steinbach, MB: Evangelical Mennonite Conference, 1962), http://mennotree.com/pennerm/index_ files/Kleine_Gemeinde_History.htm. ↩︎

- Fast, “Mitteilungen,” 63–69. ↩︎

- Alberta Pantle, “Settlement of the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren at Gnadenau, Marion County,” transcribed by Ihn, Kansas Collection: Kansas Historical Collection, vol. 13, no. 5 (Feb. 1945): 259–285, http://www.kancoll.org/khq/1945/45_5_pantle.htm, accessed February 18, 2019. ↩︎

- Funk was a well-established publisher, whose Herald of Truth was designed for members of the Mennonite Church (MC). Funk also initiated a German-language version, Herold der Wahrheit, designed to inform Mennonites in Russia of immigration possibilities. See Harold S. Bender, “Herald of Truth (Periodical),” GAMEO, 1955, http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Herald_of_Truth_(Periodical)&oldid=143294, accessed 10 Feb. 2019. ↩︎

- Harold S. Bender and Richard D. Thiessen, “Mennonitische Rundschau, Die (Periodical),” GAMEO, June 2007, http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Mennonitische_Rundschau,_Die_(Periodical)&oldid=142804. accessed 10 Feb. 2019. ↩︎

- M. B. Fast, Meine Gedichte vom Jahre 1880 bis jetzt, trans., Arn Froese (Reedly, CA: M.B. Fast, 1943). ↩︎

- Conrad Stoesz, “‘Facebook’ of a Century Past,” Mennonite Brethren Herald, 2016, https://mbherald.com/facebook-century-past/. ↩︎

- Fast, “Mitteilungen,” 23–50. ↩︎

- M. B. Fast, Geschichtlicher Bericht Wie Die Mennoniten Nordamerikas Ihren Armen Glaubensgenossen in Russland Jetzt Und Früher Geholfen Haben: Meine Reise Nach Sibirien Und Zurück, Nebst Anhang Wann Und Warum Die Mennoniten Nach Amerika Kamen Und Die Gliederzahl der Verschiedenen Gemeinden, trans. George Reimer (Reedly, CA: M. B. Fast, 1919), 4. ↩︎

- Delbert F. Plett, “Molotschna Colony – Bicentennial 1804–2004,” Preservings 24 (Dec. 2004), 1, https://www.plettfoundation.org/files/preservings/Preservings24.pdf. ↩︎

- Bert Friesen, comp., Arn Froese, trans., Mennonitische Rundschau Author Index, Volume 1: 1880–1909 (Winnipeg, MB: Centre for Mennonite Brethren Studies, 1991). ↩︎

- Cornelius Krahn, “Siberia (Russia),” GAMEO, 1959, http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Siberia_(Russia)&oldid=162415, accessed 10 Feb. 2019. ↩︎

- Friesen, Mennonitische Rundschau Author Index, trans. Katherine Yamada. ↩︎

- Fast, “Mitteilungen,” 77–79. ↩︎

- Kevin Enns-Rempel, Director, Hiebert Library, Fresno Pacific University. Email July 17, 2017 on file. ↩︎