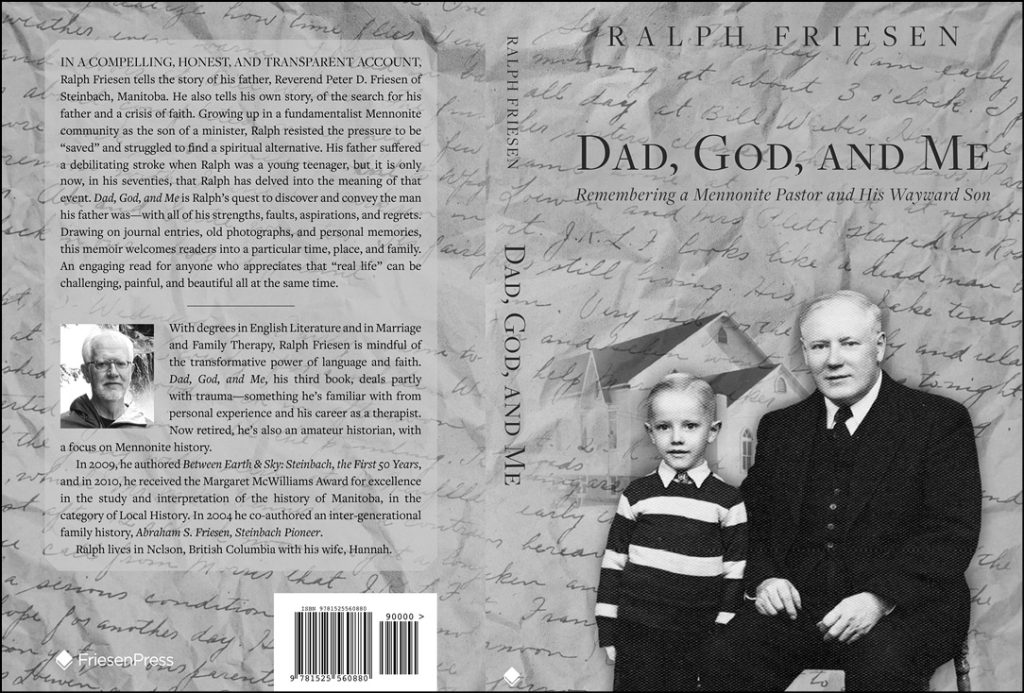

Dad, God, and Me

Ralph Friesen

How many of us have told a story and had someone say, “You should write a book”? And we think, “Maybe I should,” but for various reasons we never do it, and the story goes unpublished, and when we die, it dies with us. The world loses that story.

Which also would have happened with this story, of my father, and of my spiritual journey as it was shaped by him. Except that I was determined that this story should not be lost. Actually, no one suggested that I write it – this was my idea. Other biographies of church leaders of his time have been published, and I thought: “If them, why not him?” He was not as strong a personality as some others, and his influence on church affairs was not as great as that of some others, but even so, he had his moment in history, and it mattered, and I wanted to give him his due.

I also wanted to give the story of my own rebellion, apostasy, lack of faith – whatever you want to call it; I wanted to put this “forbidden” stuff out into the world. We have many biographies that are essentially hagiographies and we have many spiritual memoirs in which the writer endures trials and emerges victorious and blessed, and that’s all good. My purpose was different.

A grant from the Plett Foundation enabled me to have the book edited, designed, and laid out by professionals, and also to make it available to a broad audience online. Dad, God, and Me was published in late December of 2019, so there’s been time for some readers to respond, and share their thoughts with me. Many have been moved to share their own stories of their parents and siblings, and their experiences with faith and doubt. I invite whoever reads these words into the dialogue, too.

This is a book I’ve had in me almost all my life. It was a labour of love, and my hope is that you, the reader, will finish the circle by engaging with it. The following is an excerpt from the introduction.

My father was Reverend Peter D. Friesen, pastor of the Kleine Gemeinde / Evangelical Mennonite Church in Steinbach during the 1940s and 1950s. Twelve years ago, talking about him with my wife Hannah over breakfast at the Corner House Café in Nelson, BC, I was surprised by a sudden upwelling of sadness. I began to weep. Those tears were the seeds that developed into this book.

We were six children in my family — Alvin, Donald, Mary Ann, Vernon, Norman, and me, Peter Ralph, the youngest. When my father had his paralyzing stroke on August 11, 1958, we made our individual visits to the hospital to see him. We didn’t go together.

To whom would it have occurred to bring all of us together and ask: “What does each of you need? What can you contribute? What shall be done now, now that you have lost your father?” (Or for my mother: “your husband.”) To no one, apparently — it didn’t happen. And this is one of the things that struck me at breakfast that day — that we each dealt with the situation alone.

“Loss,” I say of Dad, although he didn’t die. But we treated him like an imposter. This paralyzed imitation of a man, whose brain didn’t function properly anymore, was not our father. I believe we all thought that, without talking about it.

And we were wrong. Why was I crying at the Corner House? In my adolescence, after Dad’s stroke, I was embarrassed by him. He tried to be of good cheer, despite the horrendous blow that had slammed his body and brain with such terrible force. I had always thought of this effort at cheerfulness as artificial — absurd, even. But now I was struck by his lonely courage. He carried on, as best he could. He must have known that we, his children, viewed him from a cool distance after his stroke, that we didn’t try to understand his situation or connect with him. But he did not complain, or ask for sympathy. He was a brave man, far braver than I ever realized, and I had failed him. Understanding this for the first time, I wept that August morning.

When Mom died in 1983, Steinbach businessman and family friend Cornie Loewen met with us siblings regarding the settlement of the estate. He congratulated us on our spirit of cooperation. He saw that we had something, as a family. Whatever our differences, we were kindly disposed to each other.

There is for me in the memory of that estate meeting a hint of the guidance that we needed (and could not find among ourselves) after Dad’s stroke; I’m still grateful to Cornie Loewen for bringing us together and giving us encouragement. Even today, with Mom and Dad gone, Vern gone, and Cornie Loewen gone too for that matter, and the Corner House Café transformed into a different restaurant, I wish for us to gather again and reconsider that time in our lives, more than 50 years ago. Perhaps this book is a kind of gathering, and reconsidering.

I have collected everything I could find of my father — his diaries, a few letters, postcards, sermon notes, pictures. I have also drawn upon my mother’s diaries and letters. I have interviewed my siblings and a number of people who knew my father as a businessman and as a church pastor. In this process, I have made discoveries, and have come to know Dad more completely than when he was alive.

I have also told my own story insofar as it intersects with his. So this is both a biography of a man, written by his son, and a memoir of parts of that son’s boyhood. The task I set myself was not only to get to know my father better, but also to get to know myself better. Even if you know nothing about him, or me, you do know something about your own search for what has been lost, your own attempts at self-understanding. Our mutual searching, our need to know and understand — these things can connect us.

For more information on this book, please visit www.ralphfriesen.com.