Notes from the Editor

Aileen Friesen

Welcome to the first summer issue of Preservings in over a decade. After our abnormal spring, perhaps engaging with our history is exactly what is needed, as we reflect on the values and principles that matter most to us as individuals and communities. Lately, I’ve been thinking about how much we take for granted the movement of people and goods. Experiencing limited travel options and shortages on grocery shelves serves as a reminder that abundance is not guaranteed and that trains, planes, and trucks move more than just goods and people. Movement often makes possible the lives we wish to live, and moments of immobility allow us to ponder those aspirations.

Movement has been a defining theme in Mennonite history, and since the second half of the nineteenth century trains have performed an essential role in this story. As the last issue of Preservings showed, the railway shaped Mennonite life on the prairies, changing the fortunes of individuals and towns and altering the values of their communities. This current issue extends the conversation by tackling the global context. While we see some of the same themes, particularly related to economic development, the examples of Paraguay, Mexico, and Russia show how railways can help us to understand themes of entrepreneurship, collective memory, and dependency in Mennonite history.

Two of these encounters with the railway emerge out of the exodus of Mennonites to Latin America in the 1920s. We are approaching the centennial of this historic event, in which thousands of Mennonites responded to the nation-building policies of the Canadian government by leaving for new places where specific privileges related to their communities would be protected. It is interesting to think about the role of the railway in facilitating the movement of Mennonites as they spread across the region, and in connecting these newly established communities with agricultural markets.

Mexico served as the initial entry point of Mennonites into Latin America. In this issue, Patricia Islas Salinas and María Miriam Lozano Muñoz describe how Mennonites remembered the train ride that brought them to Cuauhtémoc, Chihuahua, Mexico, in the 1920s. This article focuses on how the emotion of the journey solidified into collective memories for the community, which were passed down to subsequent generations. The difficulties encountered both on the train ride and after their arrival would be used to support a collective narrative of the community’s perseverance and commitment to their beliefs.

The railway also performed an important role during the migration of Mennonites to Paraguay’s Gran Chaco. The picture that introduces this article, a desolate railway winding into nowhere, in many ways represents the establishment of Menno Colony in this region. As Burt Klassen Kehler demonstrates, from the outset of their negotiations with the Paraguayan government, Mennonites viewed the construction of a railway as essential to their economic survival. Even though they had left Canada, their goal was not to flee from the world, but to limit its interference in their lives. Yet, as Kehler shows, Mennonites were dependent on others. Despite their strong desire for the railway, without money and connections, the ability of Mennonites to influence its construction was limited. The issue of transportation routes plagued the community for decades, shaping how they interacted with their new homeland.

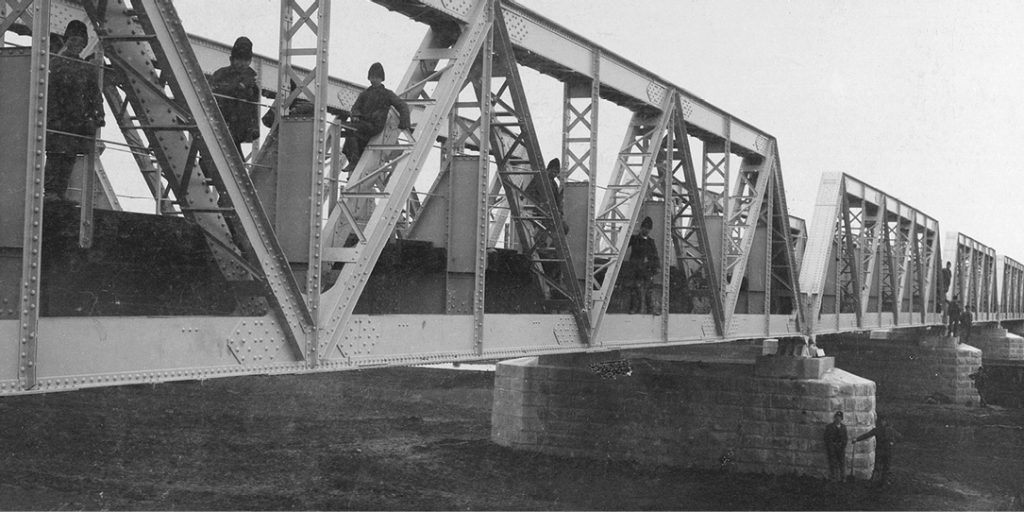

In contrast, as Conrad Stoesz demonstrates, Mennonites brought an entrepreneurial spirit to the railway cause in Russia. As the example of Johann Wall attests, prosperous Mennonites took advantage of the construction boom of the early twentieth century, benefiting financially from the expansion of the railway across the empire. The photographs for this article are especially fascinating, as they depict the material and cultural fruits of railway construction as beautified train stations became community spaces beyond those of churches and schools, where people could seek out entertainment, excitement, and adventure. These new secular social spaces created by the railway have often been overlooked in Mennonite history in favour of themes of town-planning and access to markets. But they are no less important for understanding how the railway transformed Mennonite community life.