Steinbach as ‘Host Country’: A Russlaender Family Story

Ralph Friesen

At its founding in 1874, the village of Steinbach in the Mennonite East Reserve in Manitoba was essentially an extended family. All but one of the eighteen original families who immigrated from Borozenko colony in imperial Russia (present-day Ukraine) were members of the Kleine Gemeinde church, and almost all of them were related to each other by blood ties or marriage.

As the decades passed, this ethnic/religious/familial solidarity persisted and replicated itself. Some “outsiders” did move into the village – Austrian Lutheran Kreutzers, Hungarian Catholic Soberings and Riegers, and Bergthaler Mennonite Peterses, to name the most prominent. Even these intermarried with descendants of the original families, so Steinbach retained much of its original identity.

And then, in the early 1920s, the Russlaender came. Almost immediately, the village took on a new shape. Steinbach was already something of an economic powerhouse, with various industrialists and merchants and service providers driving an ever-expanding economy. The Russlaender created their own niche in merchandising and brought new elements to village life in the form of a stronger bond with the German language and ethnicity and the promotion of education, healthcare, and culture.

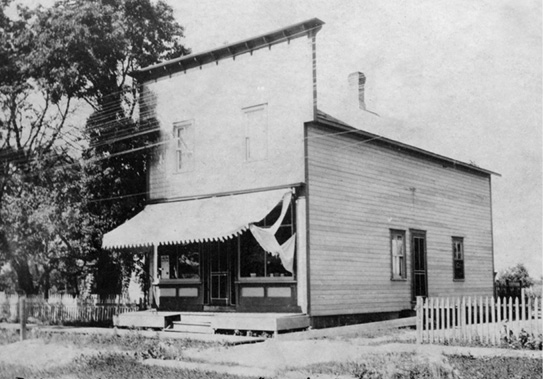

The most prominent among the Russlaender families were the Vogts. Peter Vogt ran the Economy Store while his brothers Abram and John operated “Vogt Brothers.” Both stores had similar inventory to that of the existing merchandising kings in Steinbach, the Reimers, who had the H. W. Reimer general store and the K. Reimer & Sons general store. The Vogts, however, also sold tobacco, and showed themselves to be hospitable to “outsider” groups from the surrounding area, such as the German Lutherans, the French Catholics, the Greek Orthodox Ukrainians, and the Old Colony Chortitza Mennonites.

One of the Vogt sisters, Maria, started a hospital. Another, Anna, started a kindergarten. A third, Katharina, was married to the writer Arnold Dyck, who purchased the local newspaper, the Steinbach Post. Dyck used the weekly Post as a vehicle for promoting the ideal of a German-Mennonite identity, and also for a series of Low German comic stories named after his protagonists, Koop enn Bua (Koop and Buhr).

With the coming of the Russlaender, healthcare and education in Steinbach improved, as did openness to the multicultural reality of the East Reserve and contiguous areas. For the first time, Steinbach residents could read about themselves, not only in the news, but also in fiction. The lingua franca of the village continued to be Low German, but now a more sophisticated and better quality of High German was employed by some.

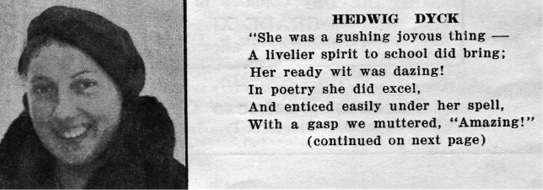

Arnold and Katharina Dyck had four children, the eldest of whom was Hedwig, born in Schoenwiese, Chortitza colony in 1919, during the revolutionary period in Ukraine. Hedwig, or Hedi as she came to be known, was an intelligent, observant child who came to Steinbach with her parents in 1923, when she was four. Shortly before her Grade 12 graduation she moved to Germany, where she became a teacher. She married a beekeeper named Wilhelm Knoop and eventually took up writing. In 1990 she published a novella titled Wenn die Erde bebt (When the earth shakes). It is a roman à clef, almost a memoir, set in “Anderbach” (Steinbach), and chronicles Hedi’s adolescent years.

Hedi Knoop calls her narrator Connie and does not provide a surname for her mother’s family, but they are clearly modelled on the real-life Vogts. Connie’s mother is called Katharina, just like Hedi’s. Many other details in the novella correspond to actual events and people; in effect, it provides a snapshot of Russlaender family life in Steinbach in the 1920s and 1930s.

In the quasi-fictional world of Wenn die Erde bebt, the narrator’s family are carriers of the trauma of events lived in revolutionary Ukraine. Principally, this trauma is revealed in the stories told by Connie’s aunts and by her father, whom she calls Krahn. These stories are not told to other residents of the village, the Kanadier. The adults in the family tell them to the children: the traumatic personal history of the Russlaender was passed on within the family. Knoop also describes the troubles in her parents’ marriage, and while she does not make a direct connection between this discord and the radical displacement her parents experienced, the reader may understand that as a possibility.

Connie’s little brother Peter (modelled after Otto Dyck) almost did not survive the trans-Atlantic journey to Canada:

Our Peter could not even sit up by himself. He had almost died on our long journey. Already in Russia he had become very thin, and on the ship we could not get a pacifier for him, nor even any milk. He had to drink from the spout of a can of tea. Soon he was deathly ill. The ship’s doctor examined him and declared that he was already dead. But mother gripped the doctor by the arm and shouted, “No, he is not dead. He’s alive! He’s still moving!” And she was right. Truly, he was still alive.1

Connie does not attribute Peter’s recovery to God; rather it is due to the mother’s strong-willed refusal to accept his fate. Peter’s survival is miraculous, but his brush with death exacts a price in later life. As a child in Anderbach he is more comfortable with animals than with humans, develops a severe stutter, and has night terrors.

Connie’s parents buy the Anderbacher Post, building and printing press and all, for a token amount and move into the attached house, but immediately they must face the prospect of repaying their travel debt:

Now we had a house and a print shop, but also a lot of debt. Everything we owned still had to be paid for, including the large travel debt incurred when we immigrated. As it was, we had not even been able to raise the money for the journey ourselves. A Canadian railway company had advanced the cash.

“As soon as we have paid all our debts and are in the black again we will move to Germany,” said my parents. “When our immigration ship was passing through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal, we would gladly have disembarked, for on either side lay Germany, the land of our ancestors. Yes, in origin and language, we are German,” they said.

From the outset, Connie’s parents signal their views and intentions. Unlike the majority of their Russlaender counterparts they do not accept Canada as their final destination. In their self-description as German, the Krahns also distinguish themselves from Anderbach’s residents, most of whom were born in Canada and have acquired English as a second language. In actuality, Arnold Dyck never became fluent in English and his sister-in-law Anna Vogt (Tante Sanna in the novella) moved to East Kildonan when Steinbach parents demanded kindergarten instruction in English. Hedi Dyck left for Germany in 1937 and was followed by her mother and siblings the next year. Arnold Dyck remained in Canada until the end of the Second World War, and then he too moved to Germany. The Dyck family’s time in Steinbach was provisional, the village a temporary stopping place until they could reach their true home.

The eldest of the Vogt siblings, Aganetha (Neta), remained in the Soviet Union at the time her siblings emigrated. She was married to Jacob Kampen, who died of typhus after less than a year of marriage and just five days after the birth of their first child. Aganetha eventually immigrated to Canada in 1948, where she was reunited with her siblings. Still another Vogt, David, died in 1920 of typhus while serving in the Crimea with the White Army.2

One of the boys died of typhus in Russia. That was my uncle David, who had no fear of thunder and lightning. When a storm was raging outside and Aunt Neta, who is very pious, was diligently praying to God, he would stand at the open door and, at each lightning flash, shout enthusiastically,

“By thunder!”“Come back in, David, don’t say that,” pleaded Aunt Neta, “God will punish you, you’ll be struck by lightning. Come in and close the door.” But no, David stayed standing at the door and said, “By thunder!”

Things were very bad for Uncle David in the terrible time of the Russian Revolution. He was discovered by bandits, who were going to shoot him. Along with many other prisoners he was forced to stand against a barn wall. Uncle David was the last in the long row of the condemned. The executions began at the front of the row; one man after another fell to the ground. While this was happening, Uncle David quietly and bit by bit edged toward the end of the barn, and in a single unobserved moment, slipped around the corner and ran.

For a long time the family had no news of David, and so Aunt Neta made a vow: “Dear God, if you bring David back to us, I will fast on Fridays for the rest of my life.”

When David did return, Aunt Neta fulfilled her promise. It was hard for her but she got used to having no nourishment on Fridays.

Only a little later Uncle David had to flee again, and this time he did not come back. No one knows when and how he died. But do you think that Aunt Neta would break her vow? No, she continued to fast unwaveringly. I do not think that was very fair on God’s part.

Although Connie concludes that no one knew her uncle David’s fate, she begins by saying that he died of typhus, and this is true to the facts. Connie’s evaluation of the justness of Aunt Neta’s bargain with God presages a later shift in her spiritual beliefs, away from the tradition of her ancestors.

Aunt Neta’s brother died, but then she suffered a loss even closer to home – her only child was taken from her:

My poor Aunt Neta suffered a very sad fate herself. As a young woman she married a very handsome man. But after a year he died, exactly on the day that she brought her first child into the world. Then, with this child, she moved back to her parents’ home. There the little boy grew up along with his uncles and aunts. At the age of twenty he, like so many others, was arrested by the secret police on unproven charges and thrown into prison.

Every morning Aunt Neta would get up and go to the high fence surrounding the prison, where she would keep a look out for her son. And one morning she saw him. His hands were bound behind his back and he, along with other prisoners, was being marched across the yard to the guard house for interrogation. With armed guards in front and behind him, her son turned his head just a little, his eyes seeking his mother through the wire mesh. When he recognized her he nodded at her with a small movement of his head.

The interrogation lasted three days, and each morning Aunt Neta stood at the fence and watched for her son. And each time, when he walked across the yard, he turned his head ever so slightly toward her, greeting her. But on the fourth day she waited in vain, and in the days that followed he was not among the prisoners. He was gone, and no one told her where he was.

She heard no more of him after that. Her whole life, she grieved for her only son. She said: “When I die, the first thing I will do is to run to God and ask: ‘Where is my boy?’”

According to A Vogt Family History, in September 1937, Jacob Kampen Jr. “was forcibly taken from his home by the NKVD, sent into exile a few months later, and was never heard from again.”3 The Russlaender immigrant inheritance is loss and lifelong grief. As well, even the pious among them had their long-held Christian faith shaken. God does not give explanations.

Aunt Sanna (Anna Vogt, the kindergarten teacher) is also a source of tales about the terrors of the past:

“Auntie Sanna, tell us about Russia,” we begged whenever we went to visit her in her little house. Again and again she would tell us scary stories, for example, the one about the mill-owner Thiessen. He was a rich man with three sons and two daughters. But his wife had died and the children had no mother.

When Aunt Sanna came back from her training in Germany, Mr. Thiessen hired her as a governess for his children. A housekeeper looked after the house management, a cook prepared the meals, and a Russian chambermaid cleaned the rooms.

Mr. Thiessen was a very busy man. He had built a large mill operation which he had to look after. So he did not have much time left for his family. But he made sure that his children were well looked after and that they studied hard in school.

He was in great danger during the Revolution. The revolutionaries were after the blood of everyone whom they judged to be an enemy of the people. According to them, Mr. Thiessen was one such enemy, as he was rich and he was German.

One night, long after everyone had gone to bed, a knock came at the Thiessens’ door. “Open up!” came the harsh command.

Everyone in the house knew that this was now a matter of life and death for Mr. Thiessen.

That is why he swiftly left his bed, threw on his housecoat, and left by the back door and hid in one of his employees’ houses. Aunt Sanna quickly made his bed and hurried to the door to let in the roughnecks.

“Where is the boss?” they wanted to know.

“I don’t know,” said Aunt Sanna.

“Is he at home?”

“No, he isn’t.”

“We’ll see about that!”

In the meantime the maid had come in and she stood there in the dress she had hurriedly put on.

“Who are you?” asked one of the men.

“The chambermaid.”

“Take us to your boss,” commanded the man.

But the girl was not an enemy of the people. She was a Russian servant and could take some liberties.

“Find him yourself,” she said snappily.

And so they searched the whole house, wakening the children, until at last they found Mr. Thiessen’s room. The bed was empty, unused.

“We’ll come back. And we’ll find him,” they threatened. With that, they left.

Aunt Sanna trembled and could not sleep at all that night.

So it went, for many nights, until Mr. Thiessen’s nerves gave way and they caught him. They dragged him out into the cold of winter to the Dnieper, where they made a hole in the ice and forced him into it. So his life ended.

Aunt Sanna told many other stories from the time in Russia, when so many died of typhus and starvation. The worst times were those when the anarchist bands fell upon the villages, robbing the colonists and refusing to leave. Aunt Sanna showed us a photograph of nineteen open coffins in which men and women lay, but also two children. We could see the cuts on their faces.

In her youth, the real Anna Vogt worked as a private tutor to the children of a wealthy mill-owner named J. J. Thiessen. Evidently the above story is a version of Anna’s real-life experience. The characterization of Thiessen as “rich and German” fits the description of many of the Mennonites who lost their lives at the hands of revolutionaries and anarchists in Ukraine. Anna appears to have been at the Thiessen home when the “roughnecks” came, aiding in her patron’s escape by making his bed so that it appeared not to have been slept in. She must have feared that her own life was at risk. Many years later, safe in Canada, the fictional Sanna shows her nieces and nephews a photograph of the Mennonites who had been killed, and the image of the corpses remains imprinted on their minds.

“Tante Anna” appears also in a memoir by writer Elizabeth Reimer Bartel, who was a kindergarten student in Steinbach at the same time in which Wenn die Erde bebt is set. Little Elizabeth, age six, listened with fascination and confusion to her teacher’s stories, and in turn relayed them to her grandmother, Mrs. Anna Reimer (nee Wiebe, married to H. W. Reimer). “Tante Anna says the Bolsheviks took their houses,” she reports. Protectively, her grandmother tries to steer her away from the gravity of the Russlaender experience: “Nothing for you to worry about.” In another exchange about Tante Anna, Mrs. Reimer responds with a remark that the young Elizabeth could not have understood: “Russlander! . . . yearning for their Alte Heimat [old homeland].”4 For a new generation of Kanadier, the Russlaender story was wrapped in mystery, with an aura of taboo around it.

In Steinbach as elsewhere in Canada, despite common origin and religion, the Kanadier Mennonites and the Russlaender viewed each other with mutual prejudice. Sociologist E. K. Francis observed: “The two Mennonite groups were divided by cultural and class differences. In the eyes of the native Mennonites the newcomers appeared worldly, overbearing and unwilling to do manual labor. The Russlaender people, on the other hand, found their benefactors, on whose good will they were dependent, uncouth, backward, miserly, and, above all, ignorant and uneducated.”5

Such prejudice is also revealed in Wenn die Erde bebt, but in general descriptions of Anderbach’s residents are relatively kind. Yet Knoop’s protagonist learns from experience to be cautious about sharing the family’s stories. The limitations of others in understanding and sympathizing are found not only in Anderbach. Connie’s friend Kitty, who is Catholic and lives in Ste. Agathe, reacts to one such story – about revolutionary Ukraine – with disbelief.

Connie, by now a teenager, tells her friend about her uncle Johann, her father’s brother, who lived in a small village called Number Two. After the First World War, bands of robbers came to the village demanding weapons and jewellery. If they could not find any, they raped the young women and shot the men:

One night in Village Number Two things got especially bad. My uncle Johann and his two oldest sons were not at home when a large gang of robbers moved in that evening. Four or five fierce-looking men pushed their way into my uncle’s house and demanded weapons.

“We don’t have any weapons,” said Hans, the sixteen-year-old.

“You’re lying!” screamed the leader, and began to tear open the cupboard doors and fling clothing and dishes onto the floor. The family stood in one corner of the kitchen, trembling.

“Where are the weapons?” repeated the leader, threatening Hans with his axe.

“We have no weapons,” said Hans again.

“You lie, you God-damned Germans,” yelled the man furiously. “Well, our axes will do, then. Come outside!”

My cousin Hans knew what he was in for. The faces of his mother and sisters turned white as the wall as he was taken out by his murderers. In the doorway Hans turned around and spoke gently: “Good night, Mother.” Out in the yard they fell upon him with their axes.

Every house witnessed murder and slaughter, and all the inhabitants who survived the massacre fled to the neighbouring village to relatives and friends.

On his way home my uncle heard of the invasion of his village and rushed to his family in the neighbouring village. His son Hans was lost, but his wife and daughters had survived.

The next morning it seemed that peace had returned to Village Number Two. Uncle Johann and his two remaining sons got ready to go and got the horses from the barn.

But a few robbers were still in the village. They sprang from their hiding place and clubbed Uncle Johann and his two sons to death.

When Connie concludes, Kitty remains quiet, and when she finally finds her words, she says, “Connie, I know that you are not a liar. But the story you’ve told – I can’t believe it. Such things cannot happen.” Connie begins to doubt the veracity of her own tale. Returning to Anderbach for the weekend, she asks her mother if it is really true. Her mother replies: “The story is true, Connie. Your uncle Johann and his sons were brutally murdered by a terrible pack of killers. But you know, those who have not experienced such times simply cannot imagine them. Perhaps it is best to say nothing more about it.”

The Russlaender can only turn toward each other for comfort; they cannot find validation for their history of suffering and loss in Anderbach society. For Connie’s mother this lack of validation has several layers. Not only is she not free to tell stories of revolutionary Ukraine to anyone outside the family, but in Canada she has lost her identity. She is a trained teacher who cannot teach, and, as if that were not enough, her husband, Krahn, does not seem to value her contribution in doing housework and raising children, whereas he singles out her sister Sanna for special attention and praise. In a conversation with another sister, Maria, Katharina voices her lament: “I was a teacher, I was independent, I had a reputation and counted in the community. Here I am no more than a housewife, I’m incarcerated, I don’t count anymore. I am a slave, Maria, nothing more.” Not surprisingly, Katharina is prone to depression and thoughts of self-harm.

Connie’s father, for his part, is also dissatisfied with Canada. In Steinbach he found security and a way to make a living, but not a home. He tells her of the lost hope of a home in Russia:

From the rich soil of Ukraine they [the Mennonites] were able not only to make their daily bread, but also established schools, churches, hospitals, mills, and factories in their villages. Their children attended secondary schools and became teachers and doctors, newspaper publishers and artists. In their prosperous colonies in the heart of a hospitable Russia the German settlers believed they had found a home.

This golden world was destroyed, and through that destruction the Mennonites must learn that Russia-as-home was a delusion. But Krahn cannot go so far as to give up the dream of a Mennonite homeland (Heimat) altogether. Russia was at best a “host country,” and even Canada, though peaceful and stable, is no more than that. The only remaining hope is Germany. Germany, for Krahn, is the land of origin.

Connie, who has spent her childhood and youth in Anderbach, feels a stronger connection to Canada than her parents do. She has enjoyed elementary school and high school, become fluent in English, and made friends. True, she is alienated by the religious culture in the village, and by the time she is a young woman, feels “more and more clearly that I am worlds apart from the doctrine of the preachers. I simply cannot comprehend their imagined ideas of sin and grace, of judgment and eternal damnation.” But she has a profound connection to the physical place, Anderbach. She forms a mystic bond with nature, especially the field behind her house, the creek, and the trees that grow at the water’s edge. In particular, she loves a certain willow tree, and the tree comes to embody a kind, feminine deity in counterpoint to the angry, all-knowing Father-God of the church:

Whenever I came to her, whether happy or unhappy, she enfolded me in her arms. She never became angry, and she never sat in judgment on my doings. But under her canopy I learned to judge these doings myself and to look for my own paths. She was there at all hours, always ready to receive my earthly feelings and to lead them up to heavenly heights.

Krahn arranges for Connie to leave Anderbach after high school to study music in Munich. She is pained to leave her family and her willow tree behind, but excited to go on this adventure, and she does not contemplate a return. Accompanied by the pantheistic spirit of the willow, she boards a ship in New York and is enchanted by the soft and melodious German that the ship’s stewards speak.

In fact, the “real Connie,” Hedi Dyck, took just such a journey, followed the next year by her mother and siblings. Some family members returned to live in Canada in later years, but not to Steinbach. Katharina Vogt Dyck survived the bombing of Hamburg and returned to Canada in the 1950s; she died in Vancouver in 1966.

Insofar as some Russlaender families, as documented in Wenn die Erde bebt, pinned their identity to the German language, or to the notion of a German Volk, they were destined to lose such identifiers to the forces of assimilation and the Nazi nightmare.

“Many a time has Hedi amused and entertained us with her song and jest,” said the writer of her 1937 collegiate yearbook character sketch. Decades later, she “returned” with the “entertainment” of Wenn die Erde bebt, in which she at last told the stories of her family’s experience, for the ears of Steinbach and beyond. I do not know whether the book was publicized in Steinbach, or whether any bookstore carried it. By 1990, German readers in the town were relatively few, and the Vogt siblings who play such a large part as models for the characters in the novella were all deceased. Their descendants, however, were and are still very much a living presence in Steinbach. For readers of German, the book is available today, on Amazon, as a record of the experiences of a remarkable Russlaender family in Canada.

Ralph Friesen has contributed numerous articles to Preservings and is the author of Between Earth and Sky: Steinbach, the First 50 Years, Dad, God, and Me, and the co-author of Abraham S. Friesen, Steinbach Pioneer.

- Hedi Knoop, Wenn die Erde bebt (Uchte: Sonnentau-Verlag, 1990). This and subsequent excerpts from the novella are my translations. ↩︎

- Here and elsewhere I have relied on two family histories for background historical information: Roy Vogt, Elfrieda Neufeld, and Margaret Kroeker’s A Vogt Family History (1994) and Erich Vogt’s The Steinbach Saga: The Story of the Vogt-Block Family & the Reimer-Wiebe Family (2013). ↩︎

- Vogt, Neufeld, and Kroeker, Vogt Family History, 55. ↩︎

- Elisabeth Reimer Bartel, “A Legacy – A Memoir,” Preservings, no. 10, part 1 (June 1997), 38. ↩︎

- E. K. Francis, In Search of Utopia (Altona: D. W. Friesen & Sons, 1955), 212. ↩︎