Stories of Russlaender Trauma

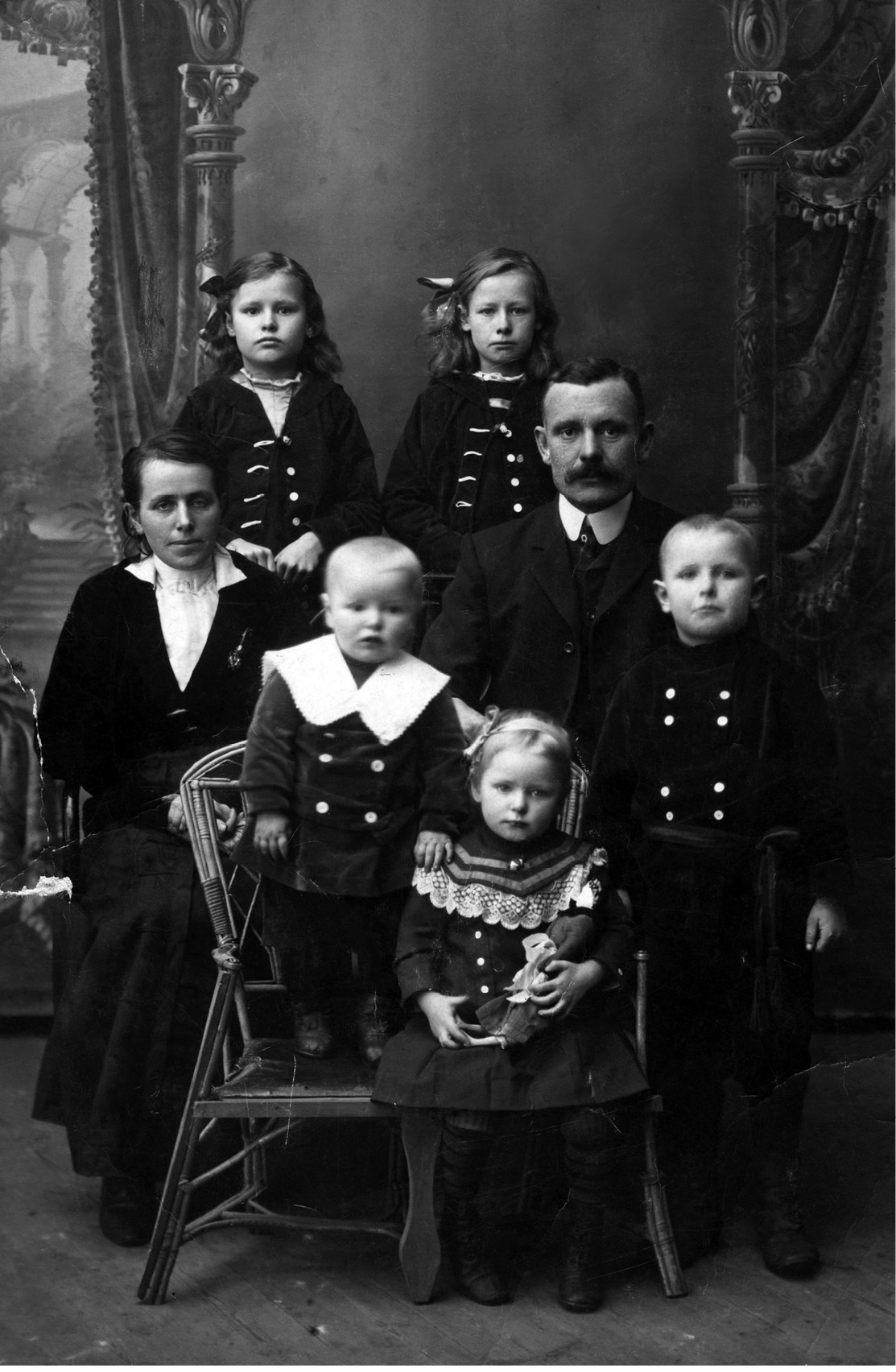

Maria Buhler and Jake Buhler

In the late 1980s, I interviewed my mother, Maria Pauls Driedger Buhler. She spoke in Mennonite Low German, and I recorded what she said in English. Much later, when I looked at my notes, I noticed that her most vivid descriptions occurred when she was recounting fear, disease, death, uncertainty, and immigration. At that time, I did not understand; only later did I realize that my mother was describing her stories of trauma. After a brief biography of my mother’s life, I will present poignant stories of trauma as she told them to me and then I will attempt to make sense of them.

Maria Buhler: A Life

Maria H. Pauls – the H representing the name of her father, Heinrich – was born on September 20, 1907, in the village of Grigorjewka (Hryhorivka, Grigoryevka) in Kharkiv province to Heinrich and Helena (Unger) Pauls. She was the second-oldest of seven children, of whom only four survived to adulthood. Her oldest sister, Helena, died of tuberculosis at age thirteen. Two sisters, Margaretha and Katherina, died before they were a year old. More tragedy would strike Maria. In 1918, when she was eleven, Maria’s mother died of tuberculosis. Ten days later her father died of the Spanish flu. She and her four-year-old brother Jacob (later minister of the Osler Mennonite Church, from 1938 to 1963) were adopted by their grandparents Peter and Helena Nickel Unger.

Peter Unger had been influenced by Radical Pietism from Germany and his spiritual expressions imprinted themselves on his children and on his granddaughter Maria. Following the Revolution, anarchism was rampant and gangs like the one led by Nestor Makhno terrorized Grigorjewka and the Unger household in 1919. Maria was frightened because she had heard rumours of what could happen to young teenage girls. In 1925, Peter and Helena Unger along with Maria and Jacob immigrated to Canada. En route they stopped in Southampton, England, where Jacob was detained for six weeks for medical reasons. The not-so-responsible grandparents continued their journey, leaving Maria to take care of her younger brother. There an exhibitionist exposed himself to her. The siblings reached Quebec City on the SS Melita in late October and arrived in Osler, Saskatchewan, following a four-day train ride on November 5, 1925.

In Grigorjewka, Maria’s family belonged to the main Mennonite congregational group (the Kirchengemeinde). But upon arriving in Osler, she was placed on an Old Colony Mennonite farmstead, with its different traditions. Maria would live on the Katharina Driedger farm, where she worked alongside Katharina’s son Cornelius. She became a domestic labourer, something she had never experienced before. Maria (age nineteen) and Cornelius (thirty-five), married in 1927 following a romance that consisted of fetching cows and picking gooseberries together. They had three sons: Leo in 1928, Otto in 1932, and Irvin in 1935. Cornelius died in 1939 of a kidney condition. For two and a half years Maria was a widow. She managed the farm and the household.

In the summer of 1941, she received a letter from her childhood sweetheart, Bernhard Buhler. He, too, had migrated to Canada and had remained a bachelor on his small farm near Winkler, Manitoba. Bernhard wrote a letter to Maria in 1941 asking whether she was interested in marriage, to which she answered affirmatively. They were married in Winkler in 1941, and moved to the larger farm at Osler in the spring of 1942. Four children were born to this marriage: Jake in 1942, Ruth in 1944, Wilfred (Wilf) in 1946, and Ben in 1951. Maria farmed alongside her husband on a dairy and grain farm. She hosted dozens of conference leaders, ministers, and evangelists when they visited Osler. She was an active member of the Osler Mennonite Church Ladies Aid Society (Naehverein). She and Bernhard moved off the farm into the small village of Osler in 1972, where they kept a large garden. In 1975 they travelled to the USSR to meet Maria’s sister Ghreeta, who had been separated from her for fifty years. It was an unforgettable reunion that also involved her brothers Jacob and Heinrich, and their wives Mary and Katie.

Bernhard died of leukemia on December 29, 1977, following a short illness. Maria continued to live in Osler, where she was actively involved in the community. She got her driver’s license at age sixty, and her green Chevrolet could be seen everywhere, usually filled with women on the way to visit yet other women. She practiced her Mennonite faith in a sort of tactile way. Once, when a group of boys were having an all-night party at a neighbour’s house, she cooked a pot of noodle soup, added some fresh buns, and brought it to them at 2 a.m. The boys were shamed into an apology for the disturbance. In 1980, she testified in German against the building of a uranium refinery near Warman. Maria moved to Bethany Manor in Saskatoon in 1987, where she lived until 2002. She kept a fine display of flowers on her balcony. Her gregarious personality ensured many social activities with friends. She joined the First Mennonite Church.

Her health began to fail in 2000 but it did not dampen her spirit. In May of 2002, following a slight stroke, she moved to Central Haven Nursing Home. It was an unhappy time for her, but she carried on bravely until her death on October 2, 2002. A large family celebrated her life of ninety-six years. A long-time friend, Esther Patkau, spoke at the two funeral services held at Osler and at Bethany Manor.

Death and Loss: Ages 11–12

I was eleven when my parents died. First my mother died, then ten days later, my father. My mother had tuberculosis and my father was suffering from the Spanish flu. As both became weaker, they were bedridden. Mother had constant bouts of fever, so she was moved to the front room (Vaathuss), which was cool. Father had chills so he was moved into the summer room (Somma Stow), which was warm. I helped look after both, trying to make them comfortable, giving them food and water and other things. They spoke to each other through the opening at the central stove. “Are you still alive?” (“Laewst noch?”) each would call out to the other. Each was worried that the other might have died when there were long silences.

One day I heard father say to Neeta (Mother’s sister), “Which child do you want when we have died?” (“Woon Kjind west du wann wie eascht daut send?”) She answered, “I don’t know but probably Ghreetchen, the youngest one.” “No,” said Father, “she will go to Ghreeta, because she was named after her aunt.” That night I wondered where I would go and who would care for me.

I saw Mother die. She was very weak and did not even get stiff (stiew) after she died. She died at 8 p.m. on September 27, 1918. As she was dying, she said, “Jesus, Jesus, Jesus, Jesus.” She said “Jesus” four times. The last time she had just enough strength to whisper the name. My sister Leena and my father also saw Mother die. I wondered what life would be like without a mother.

Taunte Marie was called immediately when it was clear Mother would die. As she neared our house, she saw a stream of light in the night sky. “Leenche is on her way to Heaven” (“Doa foat Leenche nohm Himmel”), she said. When Taunte Marie walked into the house, Mother had just died.

At Mother’s funeral the congregation sang “Angels, open wide the gate” (“Engel, Oeffnet die Tore weit,” song #15 in Der kleine Saenger). She had requested this song be sung at her funeral. She was a deeply spiritual person and partly took after her father, Peter Unger. Father attended the funeral, but he was very sick. He shivered because of his chills. He was very, very sad. Mother was bekjeat (had found God) at the time of her death; Father had not. He did not attend church much. Father was a very loving person but a bit hardened. After the funeral he begged God, “I want to go to the place where my wife is” (“Ekj well han woa miene Fru ess”). Father struggled with these thoughts, but in the end he was victorious.

A day after Mother died, friends and relatives brought butter, milk, and flour to the house. A large batch of dough was made. Then each family took a piece of dough home and baked buns, which were then taken to the funeral for the meal. This is how it was done in our village. After Mother’s death, a maid – a young girl of eighteen to twenty years – came to help in our house.

Father died ten days later, on October 7, 1918, at 2 a.m. Someone woke me up so that I could see Father die. I cried bitterly. Father groaned (stahned) a lot as he was dying. Dying was so hard for him. Taunte Marie told me later that after Father died, I asked, “Now that our father is dead, what shall we children do?” (“Papa es doot, waut sell wie Kjinja nu?”).

We surviving children were divided up and sent to live with three different families. Jacob and I went to live with Groospau (grampa) and Groosmame (gramma) Unger, where we grew up until we went to Canada in 1925. After the two funerals the auction sale of our parents’ property took place. The administrator of orphans (Weisenaumt) allowed me to keep only one personal thing. I really wanted to keep both my rag doll and the set of cups and saucers. But I couldn’t. I chose the cups and saucers. That night I missed my rag doll (Koddapopp). I had no childhood because I always looked after my four-year-old brother (“Ekj haud kjeene Kjindheit. Ekj mus emma mien veea joasche Brooda sorjen”). A year later when I was twelve my closest sister Leena died. After the funeral I was feeling sad (trurijch). I stood under our mulberry tree (Muhlbaabaum) and wondered how everything would work out because things were so bleak or black (dunkel). Now seventy years later, I can say I went through very much sorrow and loneliness, but our God (onsen Gott) was always with us.

Bandits and Fear: Age 12 or 13

I can’t exactly remember but I was twelve or thirteen when the bandits came to our village (aus dee Baunditen noh ons Darp kommen). It happened very quickly – they got off their horses and went into the big living room (Groote Stow) of my grandparents’ house. Some of my uncles and aunts were also there. The men were lined up on one side and the women on the other side. The bandits said they would shoot anyone who would not do as they said. I clung tightly to my Gramma’s long dress (Gross’mame ehre lanket Kjleid). There was confusion (aules wia vedreit). They put food and clothing into their sacks. It was very noisy. While this was happening, I remembered I had heard from older girls that they were afraid of what bandits might do to girls if they would get taken away. Then suddenly out of nowhere my young nineteen-year-old aunt, Liese, whom I shared a bed with, came into the middle of the room with her guitar and started singing songs she had learned in school. The whole room turned silent. Not a sound except for Liese’s singing, especially folksongs (Volkjsleeda). Then the kommandant faced my Groospau and spoke to him. My Groospau understood the Russian language. “This singing has done something to us. Our hearts have melted. We have frightened all of you. We will leave now.” And they got onto their horses and left.

But one time when four bandits came to our farm (Wirtschauft), there was actually something funny that happened, and I don’t know if I should laugh about it or not. You see, the bandits stole Groospau’s wagon and went to where the grain was stored. They began to load sacks of grain onto the wagon. As this was happening, Groospau began telling stories to the bandits about all the troublesome spirits (boese Jeiste) in the village and how they were breaking machines and frightening animals and scaring people. He knew how superstitious they were. As he was speaking, he began to loosen the four hubs of the wagon, unbeknownst to the bandits. When the wagon was full, the bandits left. No sooner had they reached the main street (Hauptgaus) than the first wheel fell off the wagon. Then a second one fell off. The horses were so spooked (veaengst) that they jumped uncontrollably and ran down the street spilling some of the grain. When the bandits were able to stop the wagon, they were so frightened that they unhitched the wagon, got on their horses, and left the village. Groospau meanwhile retrieved the wagon having lost none of his grain. We thought Groospau was clever!

Church and Spirituality: Ages 15–16

When I was about fifteen, I began to think about spiritual things seriously. My father had not gone to church much before he died but my mother was very spiritual. My Groospau, Peter Unger, was very much opposed to my parents’ marriage. Groospau was concerned about Heinrich’s salvation (Seeligkeit). Groospau would kneel with me before bedtime and pray. My uncle Peter Unger studied in Switzerland and tried to become a missionary. My aunts were also spiritual but not so much as Groospau. I had both Groospau Unger and Groosmame Nickel Unger inside of me. I loved to sing in the church choir and to be with the young people. Studying the catechism was enjoyable. Groospau made me feel guilt (Schuld), but Groosmame made me feel assurance (Vesejchrung). Even after I went to Canada, I carried both inside of me.

Immigration to Canada: Ages 17–18

Things were very bad by 1925. We had gotten through the famine (Hungaschnoot), but the new government that had killed the Tsar and his family was making it hard for us to live with any freedom. Buying and selling became difficult. Paper money became worthless. My grandparents decided to go to Canada. We got our visas. I had a special friend, Bernhard Buhler, but because we thought we would never see each other again, we agreed to stop our small relationship.

We arrived in Southampton, England, to get our health checkups and final travel papers. But sadly, my eleven-year-old brother, Jacob, was thought to have glaucoma. We were very sad. I cried for Jacob and that made Jacob cry. And that was not good for Jacob’s eyes. After one week our grandparents told us they were getting on the next ship. Groospau said I could manage. I was very afraid because I could not speak English and how would I manage with Jacob? I was afraid I would lose our travel papers. My grandparents had left us behind. I remembered thinking that I was completely alone (gaunz auleen) once more.

Each morning I got up worried how little Jacob was doing sleeping all by himself with the men in the sleeping sheds. But what scared me more was a man who showed himself off (waut deed sijch selvst aufwiesen). It frightened me a lot, but I did not know what to do. I was frightened to walk around that dark corner. For five weeks we lived in the sheds eating strange food and waiting and waiting. Finally, we were allowed to leave.

For two weeks, I think, we were on the ship called the Melita. Sometimes we got sick, but it was better than living in the sheds. We reached Quebec City on November 1. Then we spent four days on the train, travelling day and night. We finally reached Osler, Saskatchewan, on November 5, 1925.

New Customs, New Life: Ages 18–20

So, I ended up on an Old Colony Mennonite farm at Osler that belonged to Katharina Martens Driedger. Her husband Johann had died five years earlier. He was a very devoted member of the church but was excommunicated because he drove a car and because he was also a store owner and had a post office at Clark’s Crossing. Katharina died almost right after I arrived at the farm. That funeral was very different from those in Grigorjewka. All the traditions were different.

I was put into a room that I shared with my eleven-year-old brother Jacob. That was not easy because I was like a parent to him, but really, I was the older sister. Sometimes he did not listen to me. One night a few days before Christmas, Jacob began to cry in his bed. I went to his side to see what was wrong. He was afraid there would be no gifts for him in the bowl. Next day I went to the Osler store and was able to buy halvah and two toys for him. On Christmas morning my little brother was very happy. I was happy because he was happy. Jacob and I were in the same house as the farm owner, who was Cornelius Driedger. Cornelius was not married. I was like a maid on this farm. This was new as well. In Grigorjewka most of the maids were Russian. I went to school the first winter to learn English. My mathematics was good. There was no church building at Osler, so when a minister came around, we worshipped at the schoolhouse.

Gradually Kjnals (Cornelius) took an interest in me. When I picked gooseberries, he helped me, and when I chased the cows to the far pasture, he would come along. I had no one to talk to about this; he was thirty-four and I was eighteen. As time went along, Kjnals asked me about marriage, and I agreed. I was nineteen and a half and he was thirty-five. I felt embarrassed to marry because I was so young (“Ekj schaemed mie wiels ekj soo jung wia”). One day I came into the house and a small group of women shouted, “Surprise! Surprise!” I had never heard of a shower before. And I was in my work clothes. Kjnals wanted David Toews to marry us, so on March 10, 1927, we got on the train to Rosthern in the morning and had the wedding there and returned by train in the evening.

Less than two years earlier, I had arrived at the farm as a maid. Suddenly I was the owner of the farm together with Kjnals. Fifteen months later, on June 27, 1928, little Leo was born. I had no one to ask for advice about raising a baby because I had no family nearby. Three months later the new Mennonite church opened in Osler and that was good for me, because I got to meet more women.

More Joy, More Tragedy: Ages 21–34

Even though the Dirty Thirties (dartjche Joaren) were hard, we had quite a good life. We had more than a section of land with a small dairy (Malkjarie) of twelve cows that provided monthly income. Kjnals and I were able to help several farmers to get started, including my younger brother Jacob. We had two more sons, Otto and Irvin. Our church had a few financial problems, but we got over that. In some ways the 1930s were very good years. During these years we learned that my sister Ghreeta (Margaretha), who had not gotten out of Russia, had married and had two daughters. Later we learned that her husband, Jacob Wiens, had been shot by Stalin in 1937. It was a sad time.

But in 1938, Kjnals developed a kidney disease for which there was no cure. He came home each day from farm work tired and had much pain (Weehdoag). I felt so sorry for him. He died in March 1939. My three sons had no father, and they were almost the same age as when I lost my father and mother.

I was alone (auleen) again, but I had my younger brother Jacob and a hired man to do the farm work. I did all the gardening and the housekeeping and looked after the three boys. But nothing was more enjoyable than feeding the calves and the horses.

One day in the summer of 1941, I got a very big surprise. I got a letter from Bernhard (Bient) Buhler, who had been a friend in Grigorjewka when we were both sixteen or seventeen. He asked me if I would consider sharing my life with him. I said, “Yes, immediately” (“Jo, fuats oppe Staed”). He had immigrated to Canada a year later than I had and had remained unmarried. We married in Winkler, Manitoba, on November 26, 1941, and moved back to Osler in the spring. We were both thirty-four years old.

A Conflict of Theologies: Ages 40–42

Na jo dann (Okay, then), an evangelical revival team led by the Janz Brothers set up a tent near Osler around 1949. Our son Leo, who was twenty-one years old, got quite involved. Some members of our church were opposed to those meetings, and especially opposed to Leo’s involvement, because he was the youth leader. A congregational meeting only for men (Broodaschauft) was called. Bient said it got quite heated because he stood by his stepson. One or two people wondered if Bient should resign, because he was the ordained deacon of the church. Bient was a quiet and reasonable voice. He did not necessarily support the Janz Brothers, but he did support his stepson.

For me it may have been worse. My son Leo supported the Janz Brothers, but my younger brother Jasch (Jacob), who lived just a quarter mile from us, was opposed to the revival meetings. And he was the ordained minister of our church. So in my own family we could not agree. We met several times, and I would cry, and become quite excited. It was too much for me. Jasch said he was caught in the middle and perhaps he should resign. In the end there was peace, and nobody resigned. I found myself in the middle between the fiery Groospau Unger and the quieter Groosmame Nickel Unger inside of me. Quite soon there was healing in the church. Leo went to CMBC (Canadian Mennonite Bible College), where he changed his thinking. And strangely Jasch became a bit more evangelical.

A Reunion and A Death: Ages 68–70

In 1975, exactly fifty years after I had been separated from my sister Ghreeta, it became possible for us to travel to the Soviet Union (Russlaund). I was afraid of the Russian government, but our children said it would be safe. So my brothers Heinrich and Jacob and their wives joined us. We were on a tour, but we arranged for Ghreeta and her daughters to meet us at a hotel. For one week we were together. I cannot remember anything we talked about because all we did was cry and cry. Yes, we told stories and more stories, but when we heard of Ghreeta’s life of starvation and suffering, we cried more. Her husband had been taken away by Stalin’s soldiers. Ghreeta had just missed getting into Germany during the trek to Germany in 1944–45, and for that she was sent to Siberia with her daughters. I had not seen Ghreeta all those years, and later, after we returned to Saskatchewan, it seemed like a dream. It seemed untrue.

In 1977, my healthy husband Bient was only seventy years old. But at our family Christmas gathering he complained of a stomach ache that would not go away. So Wilf took him to the hospital, where he was told he had cancer (Kjraeft). He died ten days later surrounded by his children. At the funeral, about twelve ministers and deacons from different churches sat around the pulpit in support of Bient. We buried him beside Kjnals in the Osler graveyard. Later when I thought about what the minister had said, I wondered again about death. The minister was my brother Jasch, who I had helped to raise. He said that God had taken Bient away. That was okay, but I think I remember asking God why he was taken away so young.

Understanding Maria’s Stories

My brother Otto Driedger, a social scientist, observed that at age eleven Maria was old enough to absorb the horrific events around her and commit them to memory. Her younger brother, at age three or four, was not old enough to process those events. Otto observes that the impact of trauma may linger when there is a working memory. In her research on trauma experienced by Mennonite women in Stalinist Russia, social worker and researcher Elizabeth Krahn observes that “to live within the context of traumatic life events such as political oppression, war, and displacement is to experience persistent insecurity, separation, loss, and death – being subject to external forces beyond one’s control which shatter fundamental assumptions about self and the world.”

Maria’s traumatic stories may have been extreme ones, but they happened when other stories with similar narratives were occurring around her. The larger story was one of mass trauma impacting thousands of Mennonites. It is like a pie containing one thousand slices. Maria’s story is one of those slices. Most of those slices have no remaining or recorded story. We are fortunate that Maria’s story has remained with us. That her story has photographs, dates, names, and a script of things that happened. Without a story, people have no memory.

In today’s Canadian society children and youth are given trauma counselling when an untimely death occurs. Maria had none of that. How did she cope at age eleven when her parents and siblings died of illness and she was orphaned? How did she deal with her fears when her house and village were terrorized by bandits? How did she carry on when she was abandoned by her grandparents in Southampton, left there with her little brother? And the panic when she encountered an exhibitionist? She had no language facility to report that incident and she would have felt ashamed to talk about a taboo subject. Yet she never forgot those events – her recall was vivid.

As I reflect on it now, these traumatic experiences, although rarely talked about, had a profound impact on her. She was an extrovert by nature, with much laughter in her innards. There certainly were psychological or emotional outbursts from time to time. But in spite of suffering so much, she was able to love much. She lived a long and productive life focused on family, church, and community – free of bitterness. The literature suggests that just as trauma is inflicted because of external social, political, and historical forces (for Maria these events included the revolution in Ukraine, the Spanish flu pandemic, and the large-scale migration of Mennonite refugees to Canada), coping with trauma requires community, belonging, and support for one’s ability to make sense of the events of one’s life. Krahn suggests that one way for survivors of trauma to make sense of their lives, and to heal from trauma, is to tell their stories, so perhaps in the telling of her trauma stories, Maria was also in some way working to repair the many harms she had experienced in her lifetime.

Jake Buhler worked for 15 years as a school principal in Saskatchewan before spending 21 years in Thailand and Vietnam with the Mennonite Central Committee and the Canadian Government working with refugees and poverty alleviation. He and Louise have two daughters and six grandchildren. He is involved in a half dozen projects in Saskatoon.