In Memory of the Mennonites Who Emigrated to America

D. R.

My father, one of the first Mennonites to immigrate to the Molotschna River, settled a still empty hearth on 65-dessiatin of land in the A. village in 18081. I was two years old at the time, so I can no longer remember the hardships of settling on a deserted steppe, but from my fourth year onward, everything remarkable has remained in my memory. For example, how my mother prepared me for school (my father died an unusual death during our settlement). We had a 150-year-old picture Bible, and I have had a passionate love of pictures for as long as I can remember. My mother explained some of the pictures, what they meant, and said that when I could read for myself, then I would understand more. So I made it my business. “You must learn to read.” “Mother,” I said, “buy me a primer, I want to learn to read.” “Yes, first you must know the letters, you can’t read before that.” “I want to learn, you just have to tell me,” was my answer. I bought a Hahnenfibel [rooster primer], which I put in its own box in the evening, so that the rooster could reward me for my diligence without being disturbed, and almost every morning I had the pleasure of finding a five- or two-kopeck coin from the rooster. When I was six years old, I could read the Bible and understand some of the stories in it, such as David and Goliath, Joseph’s story, etc., for which the pictures helped a lot.

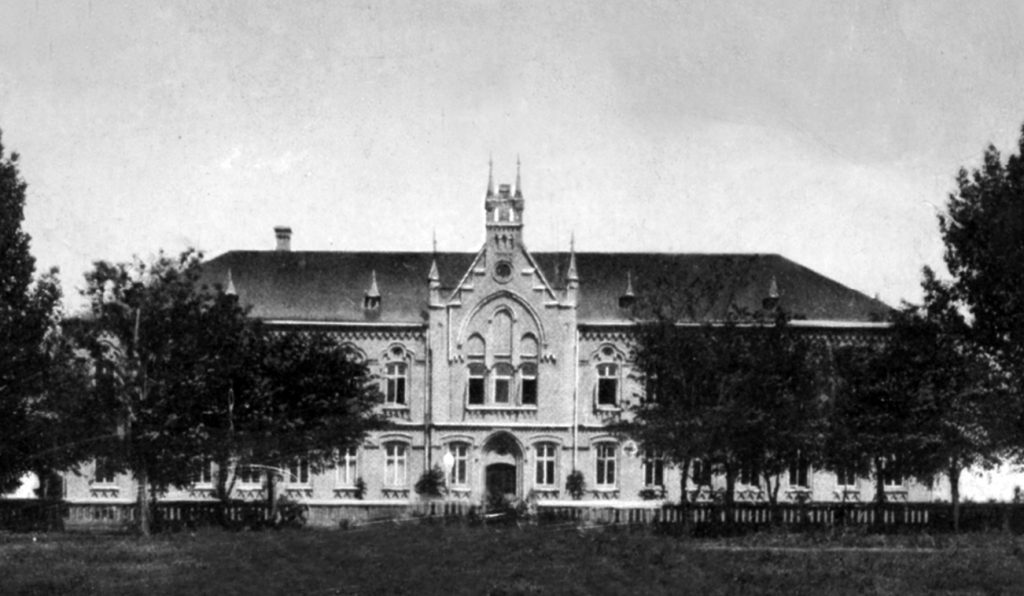

In passing, I want to describe the school as it was furnished at that time: The building, small and low, was held together with clay. In the classroom there was no furniture other than two benches along the length of the room and between them a table two feet wide and a chair for the teacher. The boys sat on one bench and the girls on the other side; the teacher sat at the end of the table. Under the table, the pupils of both sexes would get up to a lot of mischief, especially when the teacher’s eyes were closed. The latter, often a Low German, did not teach and was not allowed to teach the children any other pronunciation of the letters than the Low German way, e.g., instead of a, h, k one said oa, hoa, koa, etc. The teacher did not know anything about orthography, which was not held against him, because it was generally believed that this would instill pride in the children, and so on. I attended such a school for six winters; in the mornings and evenings, when I came home from school, I had to feed the cattle and clean the stable. In spring the holidays started, i.e., when one began to plow, and they ended only around St. Martin’s Day. Compare the schools of that time with the schools of today, and I will not be reproached for my style, as I never enjoyed any other lessons than those in that village school.

Just as the schools have improved greatly since then, so too has prosperity increased. In those days, people wore clothes made of Spanish sheepskins in winter and coarse white linen in summer: for Sunday dresses, striped linen was bought; the yellow-striped was preferred. Skirts? Some people had brought Sunday skirts with them from Prussia; others bought from the market the kind the Russians still wear today, of coarse grey cloth!

Everything has been improved since then, and with the passage of time one would think that the same has also happened morally; but about this one can rightly say: “the good old days.” There was more faithfulness and belief, and although politeness and education were lacking, many more were brought to their senses through harsh reprimands than is now the case with corporal punishment; the clergy in particular had more weight and influence than at present. The preaching profession among us is in need of improvement, for one reaches out to another; however, very few Mennonites want to know anything from a theologian or learned preacher.

For all their limitations and narrow-mindedness, Mennonites are not as closed-off as they used to be. I remember when a person of another confession came into a Mennonite’s parlour, he was not welcomed or invited to sit. This isolation also contributed a great deal to the delay in letting the children learn the national language, and even today there are some who are concerned and worried that we may become Russified if our children have to learn the national language. This is incorrect thinking. If we love our neighbours, which the Russians are, we will set a good example by respecting them and by keeping in mind the verse, “The first will be last and the last first,” and then we have nothing to fear from Russification. Yes, I love the Russians, I love the country where I was born and grew old and where I have my bread. Many are afflicted with false prejudices against Russia and prefer to emigrate to America because they think that they will find their salvation there. They have forgotten the verse: “Do good, dwell in the land and verily you shall be fed.”

Lukas Thiessen has an MA in Cultural Studies and is employed as a research analyst on Métis issues.

- Written by a correspondent from Gnadenfeld, identified as D. R. “Zur Zur Erinnerungfuer die nach Amerika auswanderungstigen Mennoniten,” Odessaer Zeitung, May 31/June 12, 1879, 2. ↩︎