Johann Eitzen: Kulak and Minister

David F. Loewen

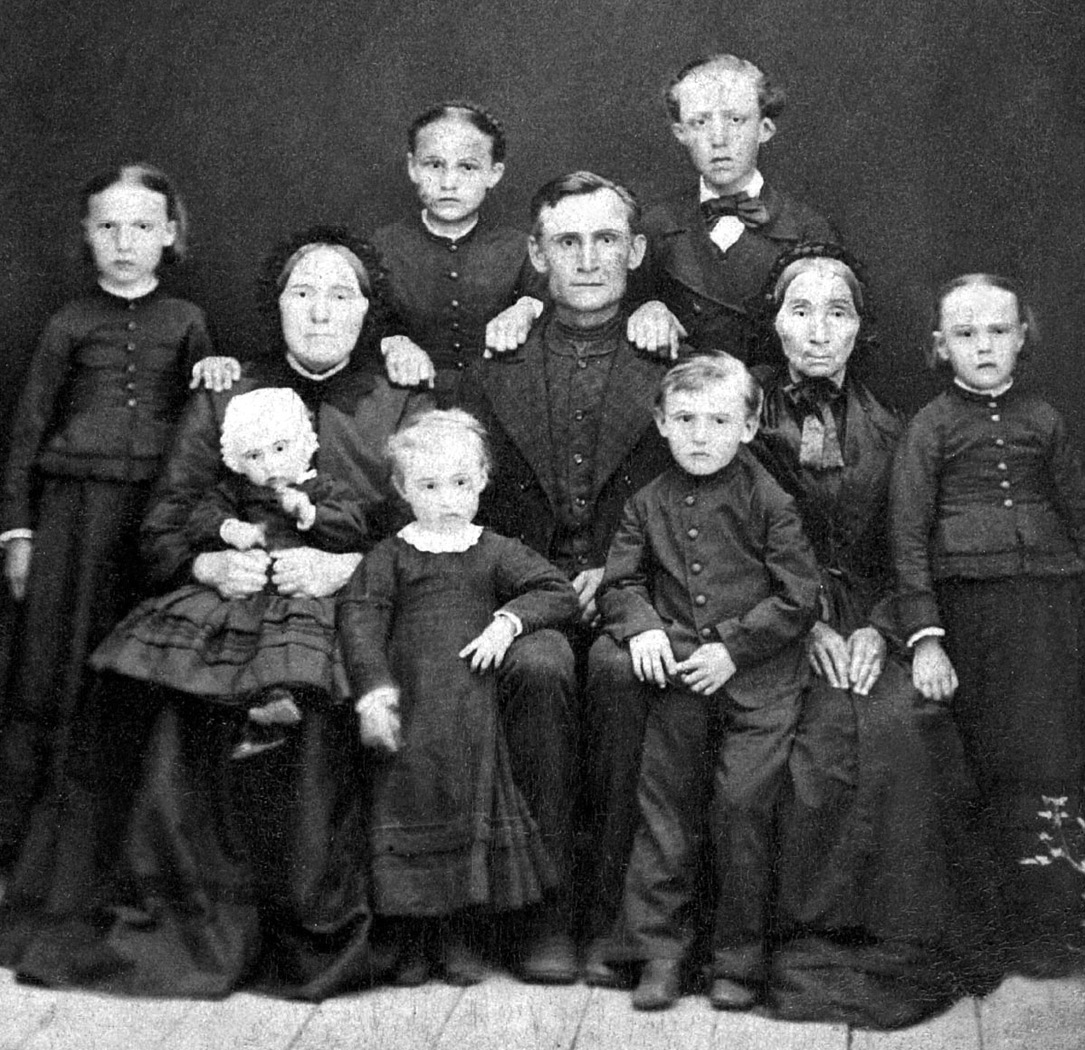

Johann Eitzen (1838–1915), born in Berdiansk, present-day Ukraine, and married to Helena Eitzen, initially settled in Orekhov.1 Their thirteen children, five of whom died in childhood, were all born in the vicinity, with Schoenwiese being the place common to most of their family events such as births and baptisms.2

In 1905, Johann and Helena moved to the village of Suworowka (Suvorovka) in the newly established Orenburg colony, in present-day Russia. The 1923 Orenburg census states that only two of their children, Daniel and Anna, joined them in this move. At about the same time, daughters Maria and Margaretha moved to the village of Pretoria with their families. Helena, Aganetha, and Katherina either remained in or later moved back to Ukraine with their spouses and families. Their son Johann (1865–1933), with his wife Maria and family, settled in the Saratov province, east of the Volga River, where he acquired a chutor (estate).3

In the fall of 1926, Johann and Helena’s daughter Maria and her husband Abraham Loewen emigrated to Canada. Maria and Abraham left siblings behind, some of whom vacillated over whether to join them. Maria’s oldest brother, Johann, had travelled to Pretoria to dissuade them from emigrating. His letter of January 1933, addressed to Abraham and Maria in Canada, recalled that attempt: “I still remember how I once came to you with the intention of talking you out of emigrating, but when I learned that your minds were set, every one of you, I had to keep quiet, and to see your intentions as God’s will. And how beautifully it turned out.”

Not long after, Johann had second thoughts about emigrating. In July 1927, he wrote that he and his wife realized they might have waited too long, and that a degree of uncertainty had delayed a more timely decision. They had not felt an urgency to leave earlier. In the summer of 1927, they had paid a farewell visit to their former homeland in Ukraine and came away with the realization that, notwithstanding the cost of leaving, staying held little future promise:

As expected, we were on the trip south, from June 9 to July 15. After a two-year delay of our desire to visit our homeland, my wife and I took this trip. In addition, we hoped to find more potential buyers for our chutor, which also was part of our reason for making the trip, allowing us to make a more informed decision as to whether to emigrate or buy something here.

If I assume and believe that what we are experiencing now will continue into the future, I must conclude that this place is not our home, despite so many ties that should keep us here. It is and remains our homeland, but we have become alienated from it, and it holds little future promise for us; that’s why we want to leave, because it’s still possible. Much is already lost by leaving, but now it is still possible; so forward before it is too late.

Johann’s letter gives the distinct impression that they regretted not having made a decision to emigrate earlier: “We are waiting for buyers, and as soon as the buildings are sold, the work begins; we will have hope. Too bad we didn’t leave in 1925; but with God it is not yet too late. We expect to make our decisions within a short time period.”

He then commented on the process involved in securing permission to emigrate to Canada:

One more question: Are you aware that the Board [Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization] has a competitor, Mennonite Immigration Aid, in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada? I have a letter promoting British Columbia through the company mentioned. It is supposed to be an association, and under the protection of the Canadian government, but operated by Mennonites. The president is a Doctor Gerhard Hiebert in Winnipeg, and the secretary is a Mennonite lawyer, Abram Buhr. . . . This society does not involve itself in missionary work but is organized for the purpose of settling Canada, and is a competitor of the board in Rosthern. . . . I ask for clarification on this.

In his letter, Johann included the usual updates on common acquaintances, family activities, the weather, the harvest just completed, and a few questions related to his curiosity about life in Canada. Mostly he related experiences from the five-week journey he had made with his wife to the southern lands of Soviet Ukraine. His comments suggest they had begun to separate themselves, mentally and emotionally, from life in the Soviet Union in preparation for the anticipated emigration:

In Niederchortitz, we stopped in to visit Mrs. Funk. Peter Loewen, who lives with her, drove us via Ebenfeld to Heubuden. My wife and I visited Ebenfeld’s churchyard and examined everything. The whole cemetery was in disarray; only the gravestone of my oldest ancestor was still standing, but our graves were even then in somewhat better condition. The mass grave is 10 steps long and 3 steps wide. Pain pierced my breast. That place was once so dear and precious to me, but now I could not bear to stay. I cast one last farewell glance before I left, probably never to see it again. At Blumenhof I gave a sermon,4 as we were staying, and it was requested by old acquaintances.

My general impressions from our journey[:] I would say that we have come to the conviction that the South [Old Colony] offers us Mennonites nothing more than the remembrance of the past, now and hereafter.

Finally, we arrived home on July 15, happy. We thought we would still be in time for the harvest; however, they were already threshing and had been interrupted by the rain. Saturday, July 23, at noon, we finished the threshing.

As for the harvest in the South, people hoped for a medium harvest. We have harvested curlew rye 45 poods per dessiatin, common rye about 15 poods, and wheat on average at 15 poods per dessiatin.5 Potatoes are fine. We did not plant much because we expected to emigrate.

What about the disagreement6 between you and your companion? Can you separate? What does “Fenz” mean? Is it meant to fence the cattle pasture? Do you also have a shepherd? What about English and German innkeepers? How is it that the farmers sell the farm and move to the city? Surely they also have children who are able to farm there, or is the farm not profitable?

We have no letters from Orenburg. Martin Loewen7 is doing well. He also has children who want to emigrate. He writes and tells us where we should go [in Canada] if we were to emigrate. We are depending on the Board in Rosthern. As I write, my wife is in bed. She has pain in her body. The Lord be with you. Greetings to all Eitzens.8

There is no record of any further correspondence from Johann Eitzen to the Loewens in Canada until a letter dated February 7, 1929. It appears from that letter that their departure was imminent, or at the least, that they were optimistic:

Letting you know that we are all well, only I suffer somewhat in my hearing9 and head. Think that when the coming trip actually happens everything will be better. Already the hope of lying down has made me happier and stronger. Particularly since February 4 when we received your letter of January 6, we’ve “been on a high.” From early to late, we are working, so that when the time comes, we are ready to emigrate.

It would also appear that Johann had moved past any hope of circumstances improving in the Soviet Union to the point that he would choose to stay. He recognized that, notwithstanding any challenges Abraham and Maria Loewen faced with in Canada, they had persevered, and there was hope of a better life: “From your dear letter we see that you are established. You arrived and made it through even though it seems difficult and with the outstanding debt. It’s a comfort to me that the Board sees it differently and offers hope.”

Much had changed in the Soviet Union in a short period of time. After the death of Vladimir Lenin in 1924, Stalin had worked to consolidate his authority, both within the Communist Party and over the country at large. In 1928 he countered Lenin’s New Economic Program with the first of a series of Five-Year Plans, which would revolutionize Soviet society. The first Five-Year Plan introduced the collectivization of agriculture, accompanied by a repressive and relentless policy of dekulakization that resulted in mass dispossession of land and forced relocations eastward of so-called wealthy landowners (kulaks) to provide the cheap labour force required to accomplish Stalin’s goal of rapid industrialization.

In a letter dated March 12, 1929, Johann expressed concern about the arrival of necessary entry permits to Canada: “We are wondering why the entry permit, even though you write that it has already been sent by the Board to the CPR, hasn’t yet arrived. Heinrich Ewerts, Klassen’s in-laws, also haven’t received their entry permits. This worries us as well.”

Johann also expressed anxiety resulting from dwindling resources. Whether he still owned his chutor or was living on property by this point claimed by the state is not clear:

Your letter of February 1 arrived on March 3. You can’t imagine how happy we were and how it brought us renewed hope and courage.

Our assets are rapidly shrinking with no end in sight. At the same time, one notices the raging destruction of what has been and what is to come, in full swing. There seems to be an urgency about it. To sum up: desolate conditions exist everywhere for us Mennonites. That which our fathers achieved and passed on to us and to which we have added is now in ruins.

We could have sold our tractor for a market value of 1,500 rubles. Not long ago a requisitioning commission was at our place and tagged the tractor at 850 rubles. Until now, we have heard nothing as to whether we would be able to keep it or have to give it up. If this is what will happen to what’s left, it can work out for us, but in the former case it screams “gone.”

A letter from Johann dated April 18, 1929, indicates the family’s tractor had been confiscated: “There is no excuse for such a tractor being taken away. We miss it very much. We don’t want to keep workers this year; we have to do everything ourselves. And yet many are crying out for work.” In the same letter, Johann states that three letters had gone unanswered (they may have been “lost” along the way). This would indicate that between February and April he had been writing letters often, and furthermore that he was anxious about their fate.

Even though the main subject of his April letter was the question of emigration and the securing of permission to leave (of which they retained a faint hope), the letter contains a tone of resignation to the fact that they might well have to remain:

We also received a reply from Moscow today regarding my enquiry of March 26 about freedom of entry. They report that they have not yet received an entry permit from the Board for us, but that they will send it to us as soon as it arrives. I fear something is wrong again, so I’m writing to you right away to ask you to be so good as to check what’s wrong.

It seems that we are to stay here, but we cannot afford to do so. And as long as there are any possibilities, we will manage, because staying here is nothing but a loss of time and effort. But we are afraid that our resources will not suffice for the journey, due to a sharp downturn and new laws. And then what? But hopefully, we will still be successful.

Johann signed off: “A letter to the Board is also going out with this letter. I have not yet finished writing to Herr Klassen. I will write to him when I get home. Greetings from us to acquaintances and relatives.”

I am not aware of any further communication between Johann and his Canadian family between April 1929 and the failed attempt of the Eitzen family to exit the country in November 1929. One can only surmise that one last harvest was taken and that attempts were made to sell off what assets were still available to him. Furthermore, the material goods assembled over the previous months10 were packed in preparation for the flight to Moscow that took place in late fall.

We are not aware of when and how Johann Eitzen notified his Canadian family11 of their failed attempt and of his place of residence. We are only aware of a letter dated January 24, 1933, from Johann to the Loewens in Alberta, in which he acknowledges a letter received from them, dated December 1932. It is through a recently published book and the memoirs of Margarete (Kroeker) Eitzen that the details of November 1929 and the following years in Johann Eitzen’s life are revealed.

In early November 1929, three generations of Eitzens – Johann and Maria with three daughters and four sons, including Johann Jr. (1893–1944), with his wife Margarete (Kroeker) and their five children, and Abram, with his wife Minna (Klassen) and child – travelled to Moscow. Johann Jr. had arrived earlier to begin the process of securing travel documents. Margarete’s two sisters and their families, Lena and Jakob Krause, and Liese and Jakob Schellenberg, joined the Eitzens. Margarete’s parents, Peter and Elizabeth (Thiessen) Kroeker, and children were waiting in Moscow as well.

Plans were put on pause as both Canada and Germany appeared unwilling to take the refugees waiting in Moscow. On November 20,12 Johann Eitzen and his son Johann Jr. were both arrested. A week later, both Johanns were reunited with their wives and children at the train station, from where all but Johann Jr. and his wife Margarete were sent back to Saratov. Margarete had gone into labour with their sixth child and was taken to a nearby hospital along with Johann Jr., who stayed with her for the night. Their five children, all sick with the measles by now, were returning to Saratov with their grandparents. Somehow, Abram and Minna and their daughter did not fall victim to arrest and forced return.

Then, as if the sea had parted, approval from Germany came. In the midst of this melee, Abram and Minna (Klassen) Eitzen and their daughter, along with the Krause and Schellenberg families,13 managed to depart for Germany. Within days, Johann Eitzen Jr. obtained his exit visa as well. Abram and Minna would be sponsored by Johann Eitzen’s brother-in-law and sister, Abraham and Maria (Eitzen) Loewen, who welcomed them in Simons Valley, Alberta, on February 12, 1930.

Johann Jr. managed to meet his Kroeker parents-in-law, who were waiting aboard the train, also ready to depart for Germany. He agonized with them about whether to join them and expect his family to follow, but realizing that emigration was for the benefit of his children, he bade the Kroeker family farewell. They succeeded in exiting the country and would find a home in Paraguay.

Johann Jr. followed his five children by train, hoping to retrieve them and return to Moscow where his wife and baby Abram would be waiting. After finding his children at a station near Saratov, permission to take them was denied. Johann Jr. was imprisoned and his travel documents and money and valuables were confiscated. His brother Daniel was dispatched to Moscow to get Margarete and her baby. Johann Jr. was only released after his exit permit had expired. Emigration was no longer an option.

Once he was released, Johann Jr.’s first priority was to ensure the safety of his parents, Johann and Maria Eitzen. Because of his father’s status as a former estate owner and a minister, it was decided, out of concern for their safety, to relocate them to another province where he would not be known.14 As a result, Johann and Maria, along with their children, found their way to Zentral, located in the Russian province of Voronezh. They were among the first settlers to arrive during the early years of collectivization, fleeing dekulakization and possible arrest. From their large chutor, east of the Volga River, via Moscow, they moved into a small shack at the entrance to the village.

Susanne Isaak writes: “They [the Eitzen family] are said to have come to Zentral very late, according to old-timers. It could have been during the collective farm period or just before. The many beautiful pictures of the private farm of the Eitzen family (threshing machine, cattle, hackney carriage with horse and cart, etc.) have been left to the ‘Mennonitische Forschungsstelle e.V.’ [Mennonite Research Centre] so that they can still be of use for later generations. . . . I myself can still vaguely remember ‘Onkel’ Eitzen. I remember that he visited our father. Since Onkel Eitzen was hard of hearing, my father spoke into a rubber ear trumpet when he talked to him.”15 It is likely the Eitzens arrived at the end of 1929, immediately following their failed attempt to emigrate. Isaak also recalls that the Eitzens arrived in Zentral with camels.16

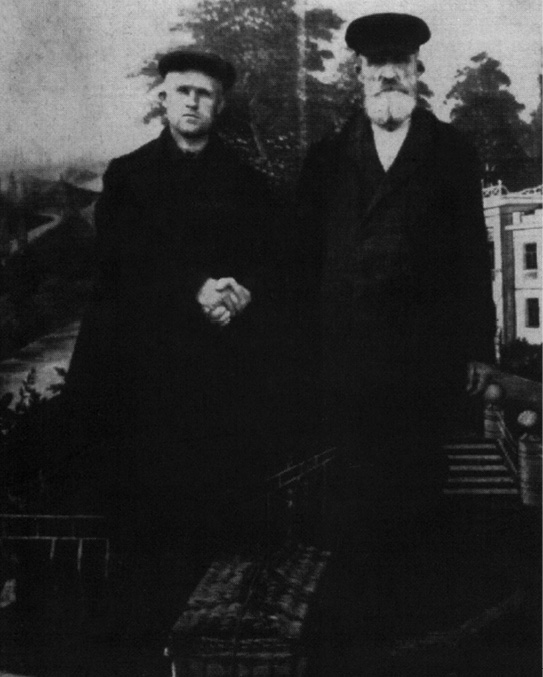

Johann Eitzen was living in Zentral at the time of his second arrest and imprisonment in Borisoglebsk, Voronezh province. He was arrested for the crimes of being a minister and having had contact with the German embassy. He was one of thirty individuals arrested at this time for counter-revolutionary activities, specifically the organizing of mass emigration of the ethnic Germans in Zentral.17 Johann was arrested on February 28, 1933, following which he was imprisoned and tortured, according to family sources.18 On the reverse side of a photo of him and his son Daniel, a time span for Johann’s imprisonment is given: “1933, 1 March, to 1933, 20 June.” Johann was the oldest of the prisoners. Isaak states that Daniel had been instructed to fetch his father from the prison.19 He died within days of being released, on June 17, 1933,20 at the age of nearly sixty-eight. His wife Maria died one month later.

Johann and Maria’s children Lena and Peter, and Peter’s wife Maria, were eventually deported, like all the Zentral Germans, possibly to Siberia or Kazakhstan.21 Their son Daniel was arrested within days of Germany’s invasion in 1941, likely suspected of “espionage” or “treason,” due to his German ethnicity. Of the ten men from Zentral who were arrested at that time, one was executed, one released, and the other eight were sentenced to five- to ten-year terms in the Gulag.22 Daniel Eitzen was one of only two who survived. At some point he married brother Peter’s widow, and eventually emigrated to Germany, where he died. The fate of his sisters is unknown.

After getting his parents settled in Zentral, Johann Jr. gathered his family and moved into the Kroeker house in Arkadak, Village No. 6. At the time of saying their last farewells aboard the train in Moscow, his father-in-law told Johann Jr. and Margarete: “Just move into our house, which we left with everything except that which we could put into our suitcases. There are still smoked hams hanging from the ceiling, and there’s plenty of flour.”23

But when they got there, everything had been emptied. There was nothing left. In Arkadak they joined the kolkhoz (collective farm), where Margarete worked first as a milkmaid and was then promoted to inspector, as she was fluent in Russian. Johann Jr. was given administrative duties. In 1937, Johann Jr. was arrested a second time. Margarete recalled: “We had settled in quite well when one night in 1937 the police came to the house, arrested my husband, and put him in prison. I was allowed to visit him in 1938 and again in 1939, each time only for a short time in the administration office. I had to travel about six hours by train.”24

A fourth son, Jakob, was born shortly after Johann Jr.’s arrest, but he never saw his father. Johann Eitzen Jr. died in exile in 1944.25 In 1941, Margarete and her children were “moved” to the northern Urals, where she and her children survived against all odds: “Here we lived very poorly and starved for almost three years. Our main food was herbs, nettles, and onion leaves, which grew wild everywhere. We mashed it, boiled it, and poured a little milk on it, which we were given. Due to the hardships and hunger, many people died here.”

In the mid-1950s, she and her children were allowed to move, as long as they remained in Asiatic Soviet Union. They opted for a more pleasant climate and settled in Frunze, near the Afghanistan border, where other Mennonites had also chosen to live. They joined a collective and were able to purchase a house. Life became much more comfortable. In the late 1980s, she joined family members in moving to Germany. When asked why she chose to move again, Margarete replied, “The constant uncertainty, also the uncertainty for the future, drove us, because as Germans we were always disadvantaged.”

In 1989, Margarete Eitzen could travel to Paraguay for a reunion with her Kroeker siblings, and three years later, she died in Pfungstadt, Germany, at the age of ninety-three. Of her six children, three are known to have emigrated to Germany, and possibly more.

Dave Loewen is a first-generation Canadian, born and raised in Abbotsford, British Columbia. He is a retired teacher and school administrator and has been serving as an elected councillor since 2005 on Abbotsford City Council. Dave has a keen interest in family history and genealogy, both of which occupy some of his leisure and volunteer time.

- Peter Eitzen obituary, Ancestry.ca. ↩︎

- The story of the Johann and Maria Eitzen family would have remained incomplete without the invaluable research done by Susanne Isaak and Peter Letkemann. Their books are rich in content and honour the memory of so many, including the Eitzens. In addition, the memoirs of Margarete Eitzen have revealed information about the Johann Eitzen family that was previously unknown to most. ↩︎

- The size and exact location of the Eitzen chutor is not known. The Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization record for Johann’s son Abram indicates he lived in Saratov, Andrejewka, until the day of his departure for Moscow in the fall of 1929. Lending credence to the conclusion that Johann was an “affluent” landowner, his letter to his sister in 1927 states that they returned home from a month-long trip to find the harvesting almost complete, implying that he had employees who did this work for him. The same letter states that several days were spent in Saratov, en route home, for his wife to have dental work done. ↩︎

- Johann Eitzen was a lay minister. ↩︎

- A pood was an imperial Russian measure of weight, equalling 36.1 pounds; a dessiatin is equal to 2.7 acres. ↩︎

- Abraham Loewen entered into a partnership with another family in purchasing a farm in Simons Valley, Alberta, in 1927. The partnership collapsed soon thereafter. ↩︎

- Martin Loewen was Abraham’s older brother, who also failed in an attempt to emigrate in 1929. He was eventually dispossessed of his large landholdings and exiled to the Ural Mountains, where he starved to death in 1932. Martin Loewen’s oldest son, Johann, along with his family, emigrated to Manitoba in 1925. ↩︎

- Reference to members of the extended Eitzen family that had emigrated earlier. ↩︎

- Johann Eitzen had a significant hearing impairment, which had been referred to in other communications. ↩︎

- In a letter to sister Maria in Canada, dated Mar. 12, 1929, Johann Eitzen writes: “Don’t rightly know at the moment what would be difficult to take and whether everything we wish to take will actually go. Have lots of duvets and pretty camel wool blankets and mattresses. Of camel wool, 4 pud in blankets and mattresses; pillows, blankets, beds, geese and duck feathers, 8 pud. Write whether it’s worth taking or becoming too expensive.” ↩︎

- Very likely he would have notified his children, Abram and Minna Eitzen, who had managed to emigrate in November 1929. ↩︎

- Eitzen, “Aus Moskau zurueckgeschickt.” ↩︎

- The Krause and Schellenberg families were accepted into Canada. ↩︎

- Peter Letkemann, A Book of Remembrance: Mennonites in Arkadak and Zentral, 1908–1941 (Winnipeg: Old Oak Publishing, 2019), 243. ↩︎

- Susanne Isaak, Das Dorf Zentral: Unser plattdeutscher Heimatort im Gebiet Woronjesh/Rußland (Meckenheim: self-pub., 1996), 153, 155. ↩︎

- Helena Isaak (daughter of Susanne Isaak), email to author, June 2022. ↩︎

- Letkemann, Book of Remembrance, 273. ↩︎

- Email exchange with Anne (Eitzen) Regier, Nov. 2021. Johann’s son Daniel eventually emigrated to Germany and visited his Eitzen relatives in Canada in 1972. He shared with his nephew Abe Eitzen (Alberta) how his father had been tortured in prison. ↩︎

- S. Isaak, Das Dorf Zentral, 154. ↩︎

- Letkemann, Book of Remembrance, 275. ↩︎

- H. Isaak, email. ↩︎

- Letkemann, Book of Remembrance, 301. ↩︎

- Eitzen, “Aus Moskau zurueckgeschickt.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Letkemann, Book of Remembrance, 346. ↩︎