Training Orthodox and Muslim Youths: Johann Cornies and the Crown Trainees Project

Nataliya Venger

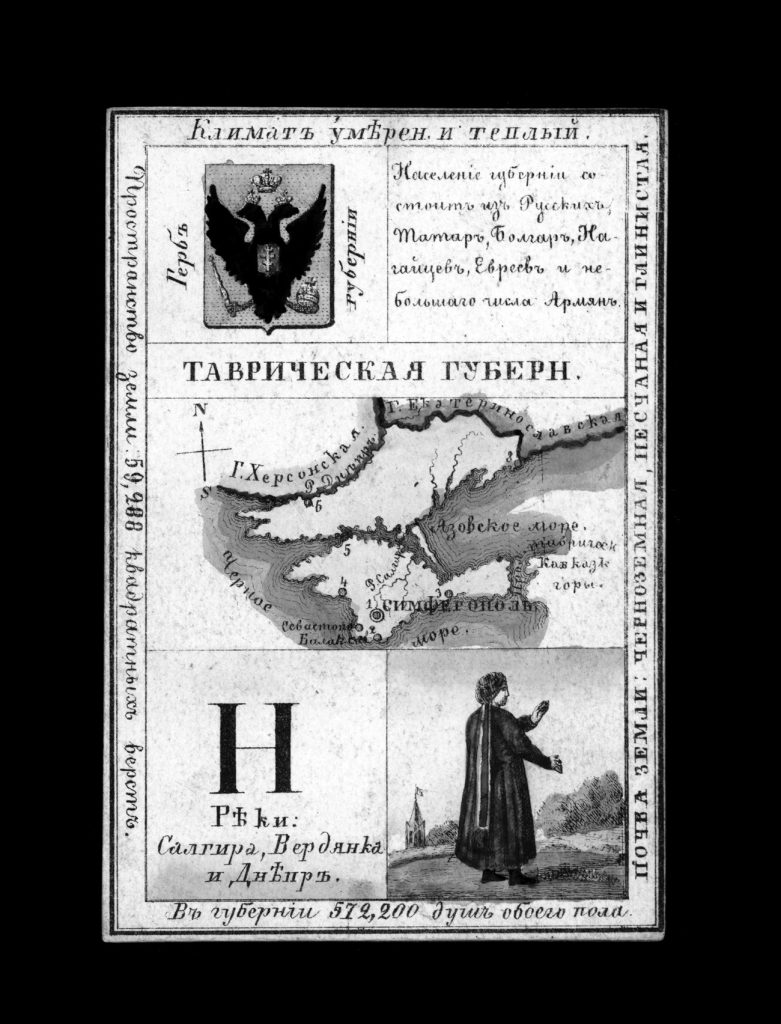

During the 1830s, the Russian empire was in a prolonged crisis, caused by social and economic problems related to serfdom (the ownership of peasants as private property) and the stagnation of agriculture. In 1837, the tsarist regime founded the Ministry of State Domains (MGI), tasking it with reforming agriculture in preparation for the emancipation of peasants from serfdom. This ministry, under the leadership of progressive administrator P. D. Kiselev, would initiate a new program, the “Crown Trainees Project,” to train youths from state peasant settlements in innovative methods of agriculture. Unlike serfs who were owned by private individuals, state peasants farmed state-owned land and had limited personal and property rights. Tsarist officials identified Johann Cornies, the chair of the Mennonite Agricultural Society, as a useful collaborator in this project.1

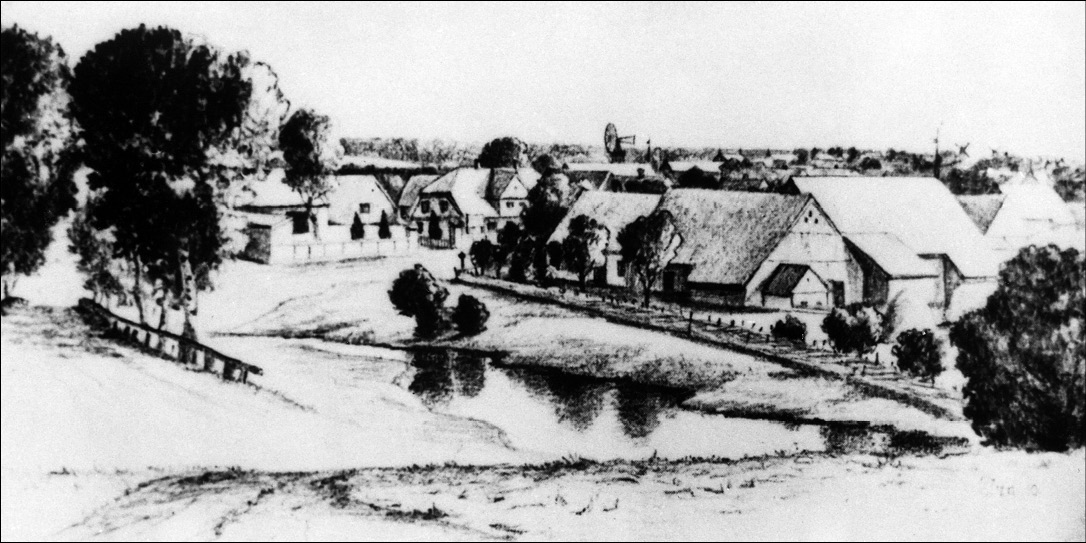

In 1841, Kiselev met Johann Cornies. Following their meeting, he wrote to his new friend: “During my trip through the Mennonite colonies, I was impressed by their organization and especially the success of your farming. . . . I told this to His Imperial Majesty. His Imperial Majesty allowed me to convey that he is familiar with the name Cornies as one that belongs to a worthy and useful man.”2 A. P. Zablotsky-Desyatovsky, a MGI staff member, also wrote enthusiastically about the Mennonites: “These colonies truly constitute a large-scale experimental factory and model farm that is progressing and striving for improvement. . . . Under these circumstances, teaching Russian landowners with the improved farming methods adopted in these colonies would undoubtedly be beneficial for domestic agriculture. It would significantly extend the beneficial influence of Mennonite colonies to the most remote regions.”3

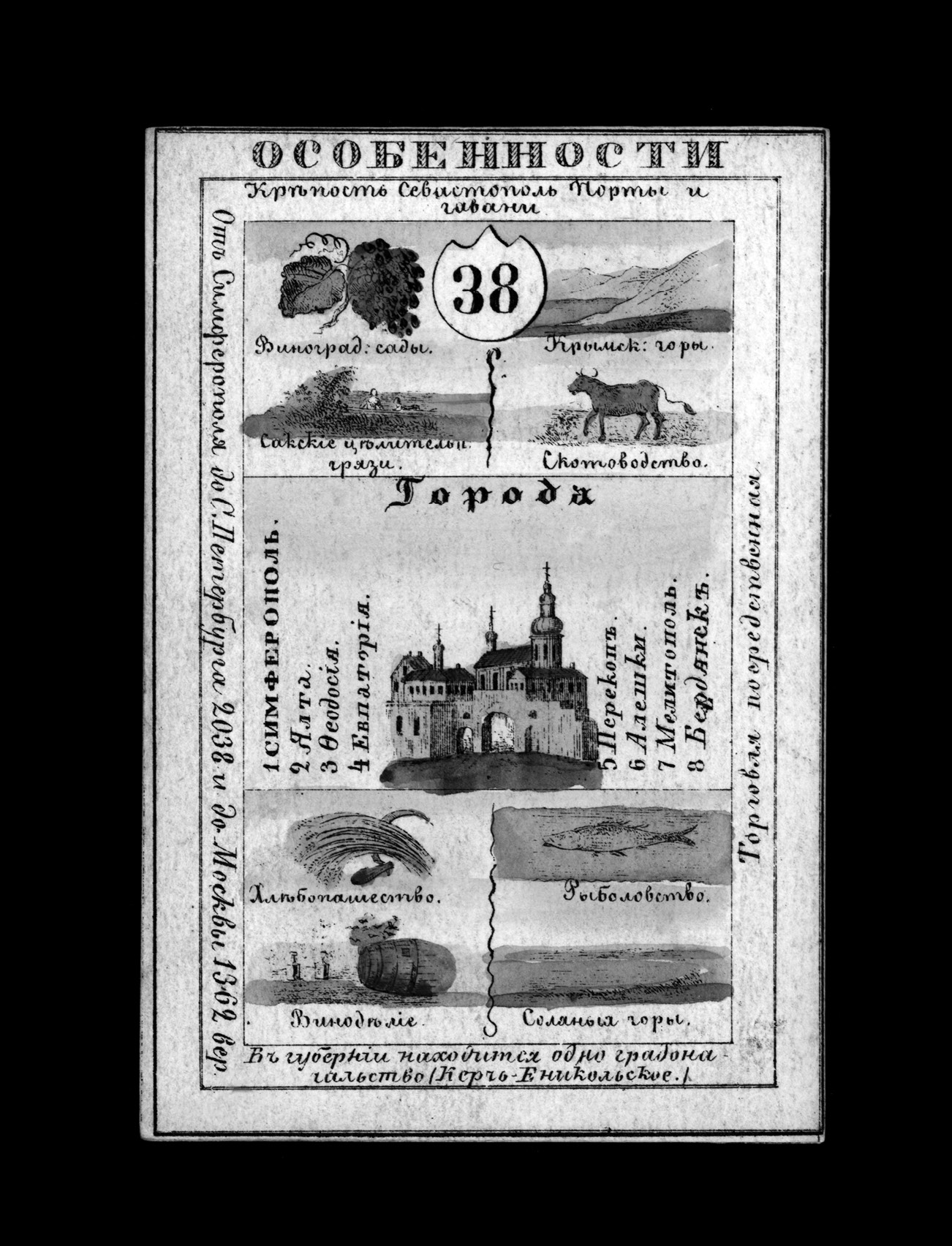

The Third Department of the MGI took responsibility for this project. Its duties included organizing farming competitions, interacting with scholars and economic societies, as well as monitoring agricultural innovations. E. F. von Bradke, who was appointed to the position of director of the Third Department in 1839, actively collaborated with authorities at the provincial level, including the Taurida, Ekaterinoslav, and Kherson offices of the MGI.4 From 1839 to 1848, Baron F. F. Rosen was director of the Taurida office.

Start of the Project

In 1838, H. H. Steven, a well-known biologist and botanist who had held the position of chief inspector for sericulture in the Taurida province,5 proposed to establish experimental farms to train farm managers in both Little Russian (Ukrainian) and Belarusian territories.6 Kiselev and his immediate circle planned to establish experimental farms within each province. These farms would serve an educational purpose and contribute to the dissemination of practical knowledge among the state peasants. Initially, the idea of creating two such farms within each of the fifty-two provinces of the empire was discussed.7 The authorities aimed to train over 2,200 peasants across the country (calculating around sixteen to twenty apprentices per farm). The Crown Trainees Project was part of this program.

In the summer of 1838, von Bradke received a note from Steven, who had inspected Taurida province to find a suitable location for establishing a model farm. During his visit to Molotschna colony he met with Johann Cornies. Impressed by what he had seen, Steven wrote to the MGI proposing to set up an agricultural school on two Cornies estates, Juschanlee and Taschenak.8 He offered the following justification: “The treasury is subjected to no small circumstances in arranging a new farm; it is difficult to find a suitable plot of land for it, and even more problematic to choose a worthy manager for such an estate, which can maintain many people who remain idle for much of the time. . . . Such establishments exist in Mr. Cornies’s estates. . . . Due to the size of his estates and his level of education, he far surpasses all his peers and is undoubtedly the best estate owner in Taurida province.”9 Steven believed that state peasant youth would benefit from being exposed to Mennonite discipline: “The well-known morality of the Mennonites in general and of Cornies in particular can serve as a guarantee for their proper training.”10 Steven tried to convince the ministry that Mennonites in general and Cornies in particular could become reliable partners in implementing the program.

In the same letter, Steven outlined the main parameters of the project, which he had discussed with Cornies. Cornies would coach six “Russian” students aged fifteen to seventeen (the list included both Russian and Ukrainian surnames), the study period would be of ten to twelve years, and a scholarship of two hundred rubles would be paid to successful students upon the completion of their studies. Mennonites would also be obligated to accept four girls, entrusted to Cornies’s wife, as well as (at Cornies’s initiative) four Nogai and the same number of Tatar boys. While the proposal did not indicate that Cornies would be paid for his work, it can be assumed that he would have received some benefit from involving his apprentices in various types of agricultural work on the estates.11 Students were not required to have had special training, but they were expected to be diligent about their work. Cornies would provide for the youths’ upkeep, although he stipulated that the government should ensure “adequate clothing” for the students. As neither Mennonites nor peasants traditionally purchased clothes, the task of providing clothing for Cornies’s students could pose a practical problem.

The central administration of the Ministry of State Domains was interested in training as many students as possible. They proposed to reduce the study period to eight years, with the aim of teaching more managers for private estates.12 Later, this term was cut down to four years. At the suggestion of Minister Kiselev, four boys from the Crimean settlements of Kyrgyz Tatars were to be trained.13 The government retained the right to terminate the experiment if the project proved to be unproductive.14

Officials, however, expressed concern about the religious influence of Mennonites on Orthodox youth. The authorities wanted the students to adhere to Orthodox religious traditions and learn the basics of Russian writing and arithmetic. Church attendance was obligatory for other Slavic Orthodox workers employed by Cornies (about seventy people), with the nearest churches located in the villages of Tokmak and Novo-Alexandrovka (later named Melitopol). Muslim students could attend the mosque in the village of Akkerman.15

Cornies declined to take on responsibility for elementary education, stating that his estates did not have suitable premises for a school. Problematically, the nearest school, located in the village of Orloff, was established with funds from the Mennonite community, and students were taught in German. The school building was too small to accept all the students, and Cornies recognized that the curriculum needed restructuring. Cornies admitted the challenge of choosing a capable Russian instructor who could competently teach while also upholding the moral qualities valued by the Mennonites. As a solution, Cornies proposed including a literate youth in the student group to teach the others. He offered to find a boy from the village of Chernigovka in the Melitopol district, where, according to Cornies, a “normal school had been operating for several years.”16 He suggested that the youth could be exempt from agricultural work, provided “he had the desire and willingness to teach.”17 Upon completing the program, this teacher would receive a payment of three hundred rubles, emphasizing that the position of a teacher should be well paid because it was respected in the eyes of the Mennonites.

Unexpectedly for the students, they received another potential privilege. During their participation in the project, both the apprentices and their families could be exempted from military conscription. Moreover, once having completed their education (provided they received a diploma), former students could be granted a lifelong military exemption.18 It should be noted that this was not a condition set by Cornies. In fact, the Russian empire had established legislation that gave this privilege to all peasants trained on model farms. This illustrates the significance that Kiselev and the Ministry of State Domains attributed to this program and to the goals of agricultural reform in general.19 However, it was uncertain whether the courses established by Cornies with the support of the MGI could be classified as a model farm. Kiselev doubted that Cornies’s students would be granted military exemption by default. He also hesitated to discuss that possibility with the Committee of Ministers, believing that “it would be difficult to obtain such a right (privilege) from the Government, and it would be more convenient to request it separately for each student.”20 The project leaders would have to revisit this issue at a future date.

After a period of negotiations, Johann Cornies signed the agreement that established the Crown Trainees Project in April 1839. As one of its clauses, Cornies insisted that the ministry would grant him freedom of action and it would not interfere in the training process.21

Difficulties and Successes: 1839–1848

The authorities intended that the Crown Trainees Project would produce managers familiar with innovative and rational agricultural techniques. However, the project encountered challenges from its inception. The primary issue arose during the selection process. As stipulated in the agreement, candidates were required to show learning aptitude, robust health, and diligence. Out of the first group of four boys (Slavic youths from the state peasant settlements) and two girls, Cornies rejected some of the boys.22 In response, the MGI urged local authorities to select candidates who could meet the requirements of the Mennonites. By November 1840, it was reported that out of the twelve youths selected (ten boys and two girls), only three boys were still actively pursuing their training: tragically, one of the youths had passed away, while six others had been sent back because of an “inability to learn, being underage, or physical frailty.”

The ministry expected that local MGI officials and the Guardianship Committee for Foreign Settlers in the southern region of Russia would actively engage with parents, explaining to them the benefits of sending their children to Mennonite colonies for free training. It decided that if such “volunteers” were not found, local district administrators should ensure the necessary number were met “through orders,” meaning forcibly, by pressuring families and presumably taking their children away.23

By mid-1841, the authorities had already reported the death of two peasant boys from Cornies’s first group.24 Another, Varlaam Hubka, from the village of Rohachyk in the Dneprovsk district, whose belongings had been returned to his family through the MGI’s Taurida office, was sickly.25 The Ekaterinoslav office reported that peasants were refusing to send their children to the Germans.26 It is unlikely that the authorities informed the residents of neighbouring Ukrainian and Russian villages about these tragic events; however, peasants working on Cornies’s estates likely informed others about the situation. Rumours must have circulated that children sent to the Mennonites were dying.

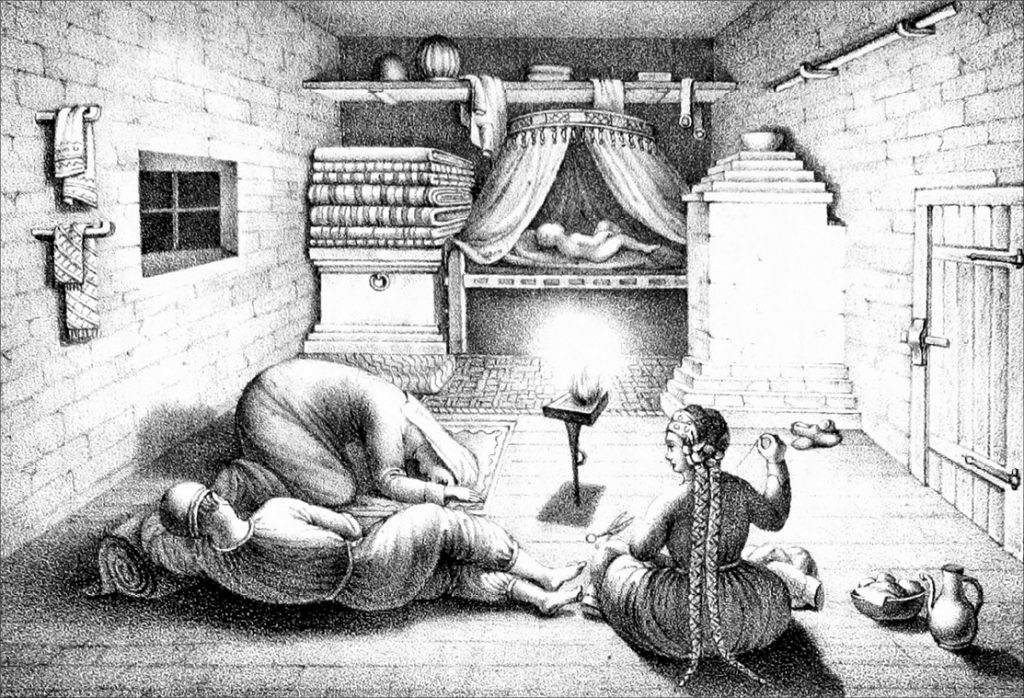

At times, the search for candidates to fill student vacancies involved the local administration literally catching orphans on the rural outskirts. Many would have been barefoot youths with weak health and personalities affected by years of wandering. For instance, orphan Yefim Zubkov was sent to Juschanlee practically “in rags.”27 Steven commented on the attitude of the peasantry: “Rural communities sometimes send those children they want to get rid of, those under sixteen years old. Parents do not send their ‘good’ children, as they need good labourers.”28 In an estate-based society, in which social mobility was virtually impossible and one’s fate seemed predetermined, parents cared little about educating their children. The family’s physical survival was an existential challenge. Peasant life consisted of daily collective labour in the fields, in order to keep from starving to death. This required an investment of physical efforts for the present and tomorrow, rather than obtaining “abstract” knowledge that might improve their future prospects.

In July 1842, Steven, who had been appointed inspector of agriculture of the southern provinces, detailed Cornies’s initial successes in his first report. A Tatar boy named D. Tuleshev proved to be the best in literacy training, with Steven noting that he “can read and write very well.” Steven also positively assessed the living conditions of the students: “The food cooked for them is excellent, the place of accommodation is dry, warm, and the clothing is very decent. Neatness, moral behaviour, and the fulfillment of religious duties, both Christian and Muslim, are observed strictly.”29

Steven also described the numerous duties of the students, including tilling, haymaking, potato cultivation, tending to livestock, gardening, and working in the wood plantation. Older students were involved in flax processing, field clearing, treating livestock diseases, crafting simple tools, grafting, and planting trees.30 In listing the students’ responsibilities, he suggested that the duration of training should be extended, acknowledging that comprehensive mastery of various skills can take more time. Steven’s comments on the level of preparation of the peasant girls were positive, noting that “the girls are diligent and well-behaved.” The inspector was enthused about the progress of the project, proposing to reward the students with small gifts.31

The inspector did not overlook certain difficulties in the students’ adaptation: “Considering that the boys joined the trainee group without the slightest understanding of proper farming, and the Nogai did not know the Russian language, and that the entire first year they were distracted from their sometimes not very commendable customs, some of them occasionally felt melancholic, while others used to fall ill. One cannot help but be quite satisfied both with the manner of their maintenance by Mr. Cornies and with their successes in both agricultural and moral respects.”32 Based on the report, the authorities concluded that “some [students] show themselves to be very good future managers.”

As a mentor and teacher, Cornies was very demanding of his students. Yusuf Aliyev complained to the chief of the Melitopol District Police Office that he had received a beating from Cornies. During the investigation, Cornies reported that Aliyev had been lazy and refused to perform tasks assigned to him and other peasant boys. As punishment, Aliyev was ordered to look after cows, and in response, he ran away. Cornies wanted Aliyev to be disciplined by his father and then returned to the place of training.33 Cornies was also accused of using his students as hired workers instead of teaching them. In his defence, he explained that practical activity was crucial for skill acquisition: “Common sense proves that apprentices can only learn the knowledge they need through hard work.” He demanded that Aliyev be punished for providing false information.34

Other evidence suggests that Cornies genuinely cared for students who showed potential. In 1842, he petitioned for student Pavel Shkurka to be exempt from conscription.35 Cornies reported that Shkurka’s “excellent achievements and morality” meant that he would be “very useful to rural society.”36 Cornies repeated his previous request that all students be allowed to stay with the Mennonites until the end of their training.37 Approval was granted by a personal order from Kiselev, who informed Emperor Nicholas I about the decision.38

Changes to the Rules

Steven’s report prompted discussion about the future of the project. Cornies insisted it was necessary to extend the training term for another year. He also suggested settling the first group of graduates in two villages: a “Russian” one (for the Russian and Ukrainian boys) and another one for Tatars. Cornies hoped that his students would live and work together, providing mutual aid to each other. He explained that in such an experimental village, “one could support the other. If only one trained peasant lives in a village, his voice and practical example could be lost in the crowd adhering to old customs.”39 This statement contradicted the original 1839 plans of the ministry to disperse the trained youths to various villages and households, believing they could provide an example and disseminate new agricultural knowledge.

To optimize the project, Cornies suggested creating families from the young men and women who had been trained in the colonies. Cornies promised to persuade his students to marry each other.40 However, without explanation, Cornies stopped training girls after 1845. By the autumn of 1845, the peasant girls (E. Dudkina, M. Bichek, and M. Shelukhina) had completed their terms and returned to their villages. Cornies demanded that the government provide them with the promised remuneration (fifty-four rubles and fourteen kopecks).41 The MGI decided to postpone the payments until they married.42

Despite Steven’s support for Cornies’s proposal to create experimental villages, the ministry expressed hesitation. The ministry decided to seek permission from parents to settle their children independently, away from their home villages.43 The response was predictable: parents demanded that their offspring be returned to their families. Some parents complained about being charged taxes for their sons not living with them. For example, Sylvester Blokh reported that taxes were collected from him for five census units, which included his son who was being trained in the Mennonite colonies.44 It can be assumed that parents also wanted to benefit from the money which their children would receive from the government.

The parents of the Muslim boys (D. Tuleshev and K. Kaldaliev) were also against the idea of their sons’ independent settlement. They requested placing them in their native villages but on separate private plots.45 Later, the parents consented but demanded money from the ministry for their children, according to their custom.

Cornies petitioned for an increase in graduation payments, believing that the graduates would not be able to realize their skills with a meagre capital of 200 rubles. Cornies asked to raise the grant by 150 rubles, so that graduates could use the additional capital to build a house, and the Nogai boys could purchase wives.46

In 1846, discussion about the project resumed. In May, Cornies, who was satisfied with the overall results of the training, claimed that the boys “exhibited very good behaviour and had acquired sufficient knowledge in agriculture.”47 He once again insisted on creating separate villages. Following the suggestions of Steven and Cornies, the Taurida MGI office proposed resettling the students in the former Doukhobor village of Terpenie (in the Melitopol district) and in the Nogai village of Edinokhta (in the Berdiansk district). “In such a settlement,” the office’s report argued, “they [the trainees] would establish their new farms not far from each other. . . . This would enable them to continue to avail themselves of [Cornies’s] advice, which would be invaluable to them on their newly established farms, and which their teacher had promised not to refuse them.”48

This model of placing well-trained peasants in one village followed the Mennonite settlement pattern of independent farming and self-government. Later, in his well-known book Nashi Kolonii (Our colonies), Alexander Klaus would consider the question of whether the experience of Mennonite settlements could be replicated in neighbouring Ukrainian and Russian villages.49 Klaus was optimistic about the prospects of imparting the experience of the colonists to Orthodox peasants: “What has been achieved in the colonies can and should be set as a goal when organizing and colonizing Russian peasants.”50

By 1847, the Mennonites had been entrusted with seventeen male and four female young peasants from Taurida province, seven from Ekaterinoslav province, and seven from Kherson province.51 The number of Mennonite instructors participating in the project had also increased. Peter Negresko and Ivan Didenko were trained under Peter Cornies (from the village of Orloff, since 1843); Joseph Litvinenko and Nikolay Dioriditsa were taught by Johann Suckau (Blumenort, since 1843); Matvey Bachkov was educated by Cornelius Wiens (Orloff, since 1844); Fedor Rabulo was entrusted to Isaac Wiens (Altonau, since 1844); and Jacob Neumann (Muensterberg) taught I. Zyubenko (since 1844).52

Over the course of nine years, the project to train state peasants in Mennonite colonies proceeded successfully and it was viewed positively by the government. However, after Cornies’s death in 1848, as his son-in-law Philipp Wiebe testified, students “were left without supervision and support” in Juschanlee.53 The parents of the students complained to the regional offices of the MGI. For instance, a letter of complaint from peasant Agafena Klyushnikova claimed that after Cornies’s death, “nobody was teaching children any skills.”54 In 1849, the Mennonites who had been under Cornies’s supervision did not receive any apprentices.

Proposed Experimental Settlements

The establishment of experimental settlements for graduates was planned to begin in the spring of 1849.55 After much persuasion, parents allowed their children to settle separately from their home communities. The graduates themselves were not opposed to being independent. However, without any explanation from the authorities, their payment was reduced to 150 rubles.56 This meant that the graduates found themselves under completely different conditions than originally envisioned. Additionally, this amount could only be received by those students who had successfully completed their training. One Nogai youth, Tibash Ogli (Kibash Ogli), received an unsatisfactory assessment at the end of his six-year term. As a result, he was sent back to his village without receiving any allowance. The Nogai boys K. Keldaliev, D. Tuleshev, S. Zhamanov, and Utai Ogli were to settle in the village of Edinokhta while Kh. Prilipko, P. Shkurko, and P. Timoshenko were to settle in the village of Terpenie.57 The ministry decided to continue strict monitoring of their activity after settlement.58 The Tatars were promised a small sum of money for purchasing wives: “A small amount is necessary, ranging from 25 to 30 rubles. . . . These funds can be provided when they need.”59

Due to bureaucratic problems related to land allocation, the process of settling these graduates was delayed. In 1848, Baron Rosen instructed an agronomist named Bauman to create a project for the settlements of Terpenie and Edinokhta, consisting of twelve households in each village.60 Family plots of fifty-nine dessiatins were to be created, corresponding to Mennonite ideas about rational farm management. Every farm would be divided into arable land, hayfields, and a household plot with a yard, garden, and orchard. Additionally, there would be space allocated for keeping small livestock, afforestation, and a common pasture.61 Commenting on the project for the village of Terpenie, Bauman stated: “I based the distribution of land for various types of agricultural activities on the recommendations from the locals, who either know the area designated for the new settlements or have lived there for over forty years.”62 The project also provided space for a cemetery, a mill, and a dam. E. F. von Bradke, who took over as head of the Taurida office after Rosen, demanded that Bauman divide the territory of the future settlement into a larger number of family plots, to accommodate both project graduates and those families of lay state peasants who would settle there at their own expense.63

Regarding the village of Edinokhta, the agronomist noted that the territory of this settlement was not as picturesque as that of Terpenie. He predicted that settlers would face challenges obtaining water, building stones, and sand. Nevertheless, Bauman considered the location a very convenient place, providing proximity to the river, the opportunity to establish proper watering for livestock, well water, and sufficient usable land for various purposes. It was also situated between two big roads leading from the district town of Melitopol to Berdiansk and Orikhiv. Melitopol was just four versts (about four kilometres) away from the future Tatar village.64

It was estimated that each family would need at least 475 rubles if the government adhered to the rules of rational farm organization (this amount included the construction of a house, purchase of livestock, and tools). The ministry considered this amount excessive and expressed readiness to change the project to reduce its costs.65 Correspondence between various departments reveals an attempt to justify the decision, which looked unreasonable ten years after the project had begun. For instance, it was remarked that “with the death of Cornies, one cannot expect success in organizing the mentioned settlements on the Mennonite model, as there is nobody to supervise.”66 P. Kiselev was a supporter, if not the initiator, of the new, restricted strategy. He ordered that only one graduate (P. Shkurko) be settled near the village of Terpenie. Ten years later, an experimental village would be founded at that location, and renamed Novopavlovka. The rest of the graduates were to be sent to their home villages, where they could “contribute to the development of their communities.” Thus, most of Cornies’s students were returned to their families, receiving a less significant payment of fifty-seven silver rubles and retaining the privilege of exemption from conscription.67

It could be concluded that the project of training peasant boys under Cornies and his peers did not achieve its full potential; however, between 1848 and 1858, six of Cornies’s graduates from the first two groups wished to settle independently in the village of Novopavlovka (formerly Terpenie), without government assistance. In the 1860s, seven farms were in operation in the village.68 It shows that living with the Mennonites influenced the character and life strategies of these young men. They gained mobility, some freedom, and a clear understanding of how to manage their households to achieve prosperity. However, when they returned to their villages, most of Cornies’s former students could not adapt to the old way of life in their families and communities.

Craftsmanship Project

The program to train young people from the surrounding state peasant communities in agriculture and animal husbandry was not the only initiative involving Mennonites. In the mid-1840s, discussions arose regarding a project aimed at sending young men from the Bulgarian settlements to receive training from Mennonites in craftsmanship. However, as A. Skalkovsky pointed out, “no matter how persuasive they were, the Bulgarians remained resolute in their decision not to place their children in the care of the Germans.”69 While the Bulgarians declined the offer, state peasants had no choice but to obey.

In 1848, Philipp Wiebe embarked on a mission to recruit young people from Ukrainian and Russian settlements to acquire skills in cart-making and blacksmithing under the guidance of Mennonite craftsmen. Information regarding the selection process has been preserved in the Molotschna community archives. As always, the criteria for choosing students were stringent, requiring them to be in good health, diligent, and to possess a sharp intellect.70

In 1850, the miller Johann Toews from Schoensee took the responsibility, somewhat compelled by the authorities, to provide seven years of training in milling to two promising young state peasants.71 This likely served as an inspiration for colonial authorities to contemplate enlarging the endeavour. In 1855, based on Johann Cornies’s experience, the MGI initiated a comprehensive state program aimed at educating orphaned peasant boys in various crafts.72 This project was successfully completed in 1859.73

In 1858, the chairman of the Taurida MGI office asked Philipp Wiebe and Johann Cornies Jr. (the son of the prominent leader) to select the best craftsmen to carry out a vocational training program for an ethnically diverse group of young men. Five craftsmen responded to the call. They were the blacksmiths Jakob Esau and Peter Hamm (from Juschanlee), the renowned mechanic Martin Heese (from Blumenort), and carpenter August Henning (from Halbstadt). Apprentices were selected from the Bulgarian colonies, which, the authorities believed, had high economic potential but lagged behind the Mennonite settlements economically. Initially, the Molotschna craftsmen were invited to move to Bulgarian villages, but not wanting to leave their congregations and the market for their products, which entailed material costs, the Mennonite craftsmen proposed the reverse option: to resettle Bulgarian youths in the Mennonite colonies. This scheme allowed both parties to benefit from the program, as it provided the craftsmen’s farms with additional labour. The Mennonites supported the students’ upkeep for the entire five years of the project.74

In total, forty-four craftsmen from the two Molotschna districts (Mennonite and German colonists) actively participated in the program. Twenty-five Mennonites from Sparrau, Lindenau, Tiege, Ladekopp, Orloff, Petershagen, Alexanderkrone, Friedensdorf, Schoensee, Rudnerweide, and Halbstadt villages were entrusted with the youths.75 Forty-five Bulgarian boys from the Southern Bug region and Izmail district were sent to the aforementioned colonies.76 Parents of the boys were satisfied with the living conditions and were content that the young men were apprenticed under the guidance of “reliable and skilful masters.”77 Although there is limited information available about the project, a letter from the supervisor of the Molotschna colonies to the Guardianship Committee dated May 6, 1863, reported the successful conclusion of the program.78 According to this correspondence, the former students underwent assessments and their professional skills were evaluated. Fifteen of the twenty-four youths participating in the examination demonstrated exceptional proficiency in their craft. Upon the completion of training in 1864, the most diligent students were rewarded with a grant of fifty-seven silver rubles.79

Conclusion

The Crown Trainees Project led by Johann Cornies, and later Philipp Wiebe, and supported by the Ministry of State Domains, represents a fascinating chapter in the history of the Mennonite colonies in the southern Ukrainian region during the nineteenth century. This initiative emerged from the government during a critical period in the empire’s history, when discussions about the abolition of serfdom and the demand for effective agricultural reform were at the forefront of the political discourse.

Cornies, an influential and innovative figure in the Mennonite community, played a pivotal role in this project, demonstrating his commitment to progress and skilful cooperation with imperial authorities. Although Mennonites were not the only ethnic group to participate in the agricultural training of state peasants, they were the only group that put forward a program for instructing artisan skills. They also continued to support voluntarily the two experimental settlements established as a result of the program.

The Mennonites fulfilled all their obligations to the program. However, after its completion, the state began to question whether its original objectives had been entirely met. These uncertainties primarily revolved around the effectiveness of the administration in managing the outcomes of the project. Despite facing challenges, the Crown Trainees Project run by the Mennonites made a significant contribution to the progress of agriculture in the Russian empire and played an important role in training a new generation of farmers from Slavic backgrounds.80

Nataliya Venger is a professor of history at Oles Honchar Dnipro National University, Ukraine, and a research associate at the University of Winnipeg.

- The “crown trainees project” is depicted in extensive interdepartmental correspondence kept in the collections of two archives in Ukraine and the Russian Federation: the State Archives of Odesa Oblast (DAOO) and the Russian State Historical Archive (RGIA). The sources about the project cover the period of 1839 to 1870. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.89, op.1, d.762, l.36ob. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.89, op.1, d.762, l.43. ↩︎

- Historical Review of the Fifty-Year Activity of the Ministry of State Domains: 1837–1887 [in Russian], vol. 1 (St. Petersburg: Yablonsky and Perott, 1888), xv. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.1–4ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.1–4ob; RGIA, f.398, op 5, d.812, ll.2–3 ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.51–51ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.1–4ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.3. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.4. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.4. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.5ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.15–16. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.16. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.28. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.50–50ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.38. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.16. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.50–50ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.146. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.39–41. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.55–56. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.82. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.75– 75ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.29. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.78–78ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.138. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.95. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.94–95. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.94–95. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.95. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.95. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.5–5ob. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.89, op.1, d.656, l.6. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.147. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.148. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.145ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.151–151ob, 170–172. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.221–222. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.221–222. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.245. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.266ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.249. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.377. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.341. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.255. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.272. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.271ob–272. ↩︎

- A. Klaus, Our Colonies [in Russian] (St. Petersburg, 1869), 101ff.. ↩︎

- Ibid., x. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.334. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, ll.293–294. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.334. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.330ob–331. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.344–345. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.279. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.371ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.313. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.344–345. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.315. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.346–347. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.347. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.345. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.347. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.174, l.366. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.8308, l.3ob. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.8308, l.4. ↩︎

- RGIA, f.398, op.2, d.8308, l.4. ↩︎

- A. Skalkovsky, Bulgarian Colonies in Bessarabia and Novorossiysk Region: Statistical Review [in Russian] (Odessa: G. Neiman and Co., 1842), 139. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.89, op.1, d.1199 (pages unnumbered). ↩︎

- DAOO, f.89, op.1. d.465, l.6. ↩︎

- “Order of the II Department of State Domains Concerning the Training of Peasant Orphans in Crafts” [in Russian], Журнал Министерства Государственных Имуществ [Journal of the Ministry of State Domains], no. 11 (1855): 33. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.6., op.4, d.18098, l.4. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.6., op.4, d.18098, l.4. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.6., op.4, d.18098, ll.5, 12. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.6., op.4, d.18098, ll.58–161. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.6., op.4, d.18098, l.187. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.6., op.4, d.18098, l.292. ↩︎

- DAOO, f.6., op.4, d.18098, l.300. ↩︎

- During the 1860s, most Nogai emigrated from the Russian empire to the Ottoman empire. ↩︎