An Autobiography

Heinrich Ratzlaff

I, Heinrich Ratzlaff, am a grandson of Adam Ratzlaff, Franzthal, who reached the age of ninety-three. My grandmother (nee Helena Schmidt) passed away in her seventies.1 Their sons were Jacob, Heinrich (who was my father), Peter, and Benjamin, and they had six daughters: Eva, Helena, Margaretha, Elizabeth, Anna, and Katharina.

When my father married my mother, nee Anna Harms, from Blumstein, she was a widow; her first husband was Peter Dueck from Elisabeththal. Mother had the following children from her first marriage: Anna, Maria, Sara, Agatha, and Peter. Sister Anna married Martin Warkentin and sister Maria married Abraham Friesen. Brother Peter married Margaretha Friesen. Sara and Agatha died single. Only two children, Helena and myself, Heinrich Ratzlaff, were born of the second marriage.

My parents lost their property through fire in 1857, after which they built nice large buildings. My father died in 1864 because of an infected hand. Two years later, in 1866, Mother sold her farmstead to Johan Dueck for five thousand rubles and moved to Borosenko. Mother did not buy any land, but lived with me on my yard, where she had a small house built for herself.

On August 26, 1868, I was married to Aganetha Janzen, and together we resided at Borosenko until 1874, where two sons were born to us, Heinrich and Cornelius. In 1874 we sold our property for two thousand rubles and together with most of our neighbours we united to emigrate to America and to establish our new homes there.

The Emigration

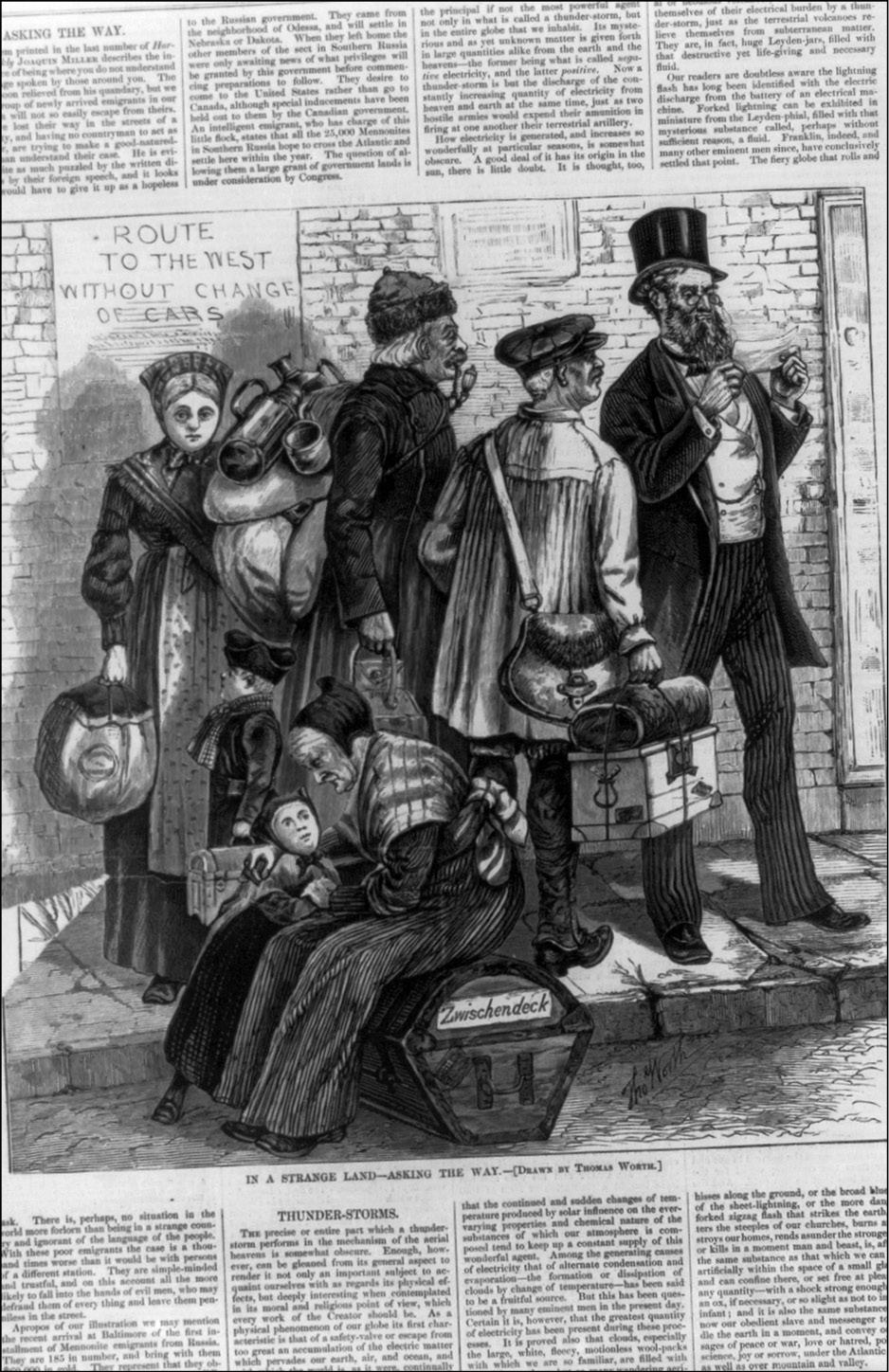

Preparations were made, and in the month of May we departed from Nikopol by boat. At this time I took on the responsibility of treasurer for this group, which consisted of sixty-four families. This job brought many difficulties as we travelled from one country to another and each time the baggage had to be paid for in a different currency. It was my responsibility to look after the currency exchanges. On top of everything else, I was sick and unable to muster any enthusiasm for these duties. But it seemed to be my lot, as I was unable to delegate it to anyone else.

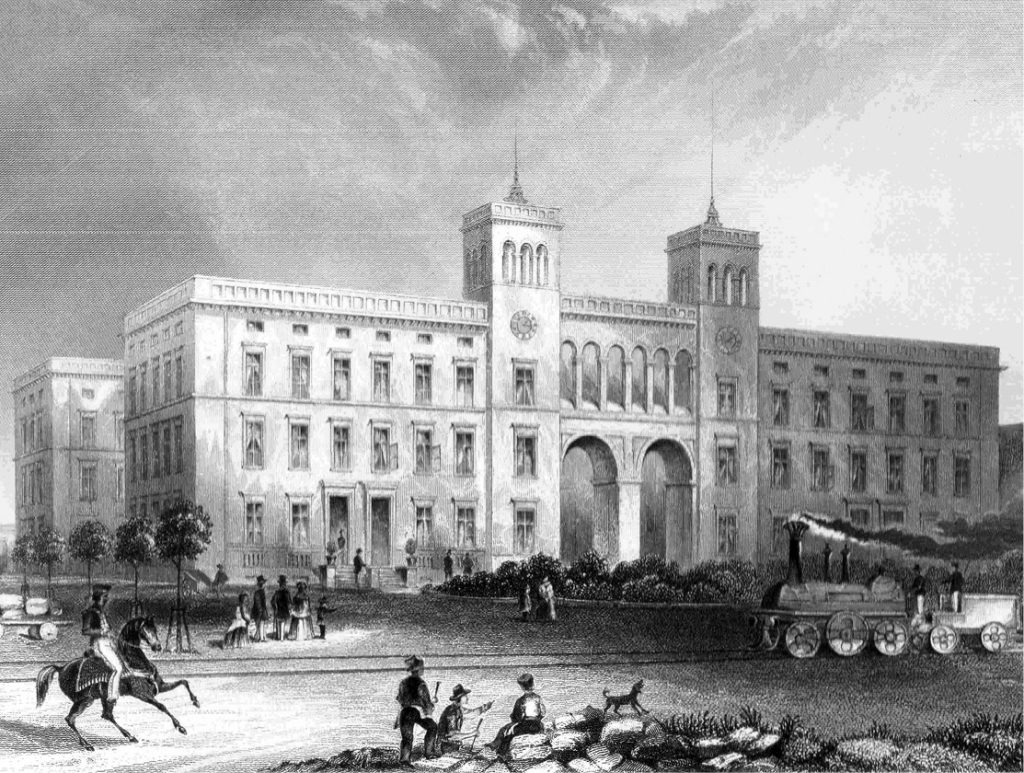

From Nikopol we travelled by ship to Odessa, and from Odessa to Hamburg by railway. We travelled through Berlin, where Peter L. Friesen died instantly. He was a brother to Aeltester Abraham L. Friesen. He had returned from Hamburg to Berlin in order to greet his parents and brothers and sisters. As he walked up the steps, which I had climbed so frequently during the time we were there, he fell down with blood streaming from his mouth and died. When his parents and brothers and sisters arrived the next day from Russia they found him already dead and laid in a coffin, and his burial took place very quickly.

Oh, how heartbreaking for his wife when she learned that her husband had died. I had taken him to the train depot in Hamburg; he had not allowed his wife to accompany him [to Berlin]. When the two of us had exchanged our final handshake and farewell he said he would rather cross the ocean than return to Russia.

By the time the Heubodner2 (the group led by Aeltester A. L. Friesen) arrived in Hamburg, we were already aboard ship and ready for departure over the North Sea for Hull. The next morning the ship took off and towards evening the ship got underway, and by Sunday at noon we arrived in Hull, England.

Every region has its own attractions and England certainly offered more than its share. We also saw many things in Germany (Prussia), where most of our grandparents were born and made their livelihood. Then the Russian tsar invited them to come to Russia to live there in peace under his protection with freedom from military service, which was a great privilege.

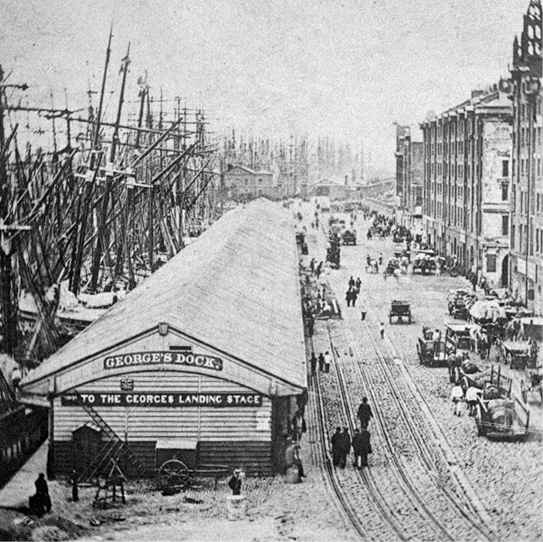

On Monday, Hull was a beehive of activity compared to Sunday, when everything was quiet, in proper repose. Monday morning our belongings and baggage were unloaded from the ship onto a railroad wagon, which was hitched to a horse, a brown gelding weighing some two thousand pounds, and hauled to the depot.

At noon, all sixty-four families and children were taken to a large yard surrounded by a high fence, in the middle of which stood a huge house, where we were all invited for a noon meal and received a nourishing repast. No one was allowed to spread their butter on their bread; in England this was all done by the efficient and lovely waitresses.

Now the time arrived that we were to travel on by railway, and after everything was packed we were underway. It was a most astonishing journey: one moment we were travelling in sunshine and the next moment in darkness. The countryside is very mountainous, and we travelled through fourteen tunnels between Hull and Liverpool, in which we were suddenly cast in total darkness.

Finally we arrived in Liverpool, where we were again able to have a good night’s rest. Tuesday our baggage was loaded into a ship that was to take us across the great ocean. The ship was called the SS Austria. Because of the outgoing tide we had to embark upon the ship and be put out to sea.

Then all of us, large and small, were examined by a doctor to see whether any serious illnesses were to be found. A railing on the large ship had been made into a divider through which every family had to pass. When Johan Klassen, who is my cousin, was examined together with his family, the doctor ordered them back to Liverpool as one of their children had scarlet fever. Oh, the pain. Cousin Klassen begged the doctor to allow them to proceed with the group. “No!” shouted the doctor, and ordered them to return to the smaller boat. With tears they had to depart from us.

I was sick already in Hamburg, with diarrhea. As we were the last to come up on deck, we were in the dilemma of also being the first in line to be examined. But the doctor looked us over and told us to go on because we were all healthy. How glad we were to hear this!

After everyone had been examined, the huge vessel was activated and the steamer was underway. The ticket had been bought to include our meals. I believe it was Tuesday morning at nine o’clock that we departed from the shore. At noon we went to be seated at the table and partook of the nourishments.

By evening the wind was raging, churning the waves higher and higher. Most of us very quickly became desperately seasick. That meant nausea, vomiting, and dizziness, so that very few ate any supper. The storm was even worse by Wednesday and the seasickness increased.

By Thursday the storm was fierce and the seas were high; the ship was tossed to and fro, the hatches and portals on the ship were closed. The sick cried and broke into frightful convulsions. I myself was struck down for a day and a half, so that my wife did not know whether I would survive.

This was the worst day of the storm. Everything that was set on the table flew off. There were also other unpleasantries like not being fully conscious. Friday, the wind, or storm, calmed down and the sickness abated as well. There were two individuals who did not succumb to seasickness, namely, Franz Froese and my mother. Every day it was announced what we would have for dinner, and on Friday we had pudding. Now and again we saw whales squirting water high into the air.

By Saturday conditions were much more bearable and by Sunday we already held worship services with singing. Henceforth we always had a lot of singing, except for a number of foggy days when it was forbidden by the captain, who instructed us through the interpreter that he was unable to hear whether there were other ships in the area and that this could result in an accident. But when it was clear and bright the captain loved to hear our singing.

After the great storm had subsided we arrived in Ireland. Many got off the ship to walk on the island, but found it strange to walk on solid ground, as we were already used to the swaying of the deck underneath our feet, i.e., to brace ourselves against the motion. As soon as the necessities were loaded we again headed out for sea, and after we had sailed for seventeen days we saw land. How joyful we were to see American soil. Before we entered the harbour a cannon was fired for a greeting signal.

From Halifax to Manitoba

The city where we had arrived was called Halifax. Here everything was transported – unloaded and loaded. Halifax was not the port of entry for us immigrants, and so we again took to sea and travelled a number of hours until we arrived at the Quebec harbour. Now the bridge was lowered and we sixty-four immigrant families had to proceed to the immigration house. Soon the train arrived and we boarded and rode to Toronto.

We were now in the care of the American [sic] Mennonites and again at an immigration house. For the first time we received a meal on terra firma. Unfortunately, it did not sit well with our stomachs and by two o’clock at night we were occupied with our distress. Many were just able to make it out of the building where they squatted and were relieved to do what was necessary.

When morning came, what a sight in the house and all around outside. Seemingly, no one had made a mess inside the building. Nevertheless, two elderly brethren, namely Frank Froese and Gerhard Schellenberg, cleaned the floor. There seemed to be a general belief that it must have been horseflesh which was offered to us, but this remained only a suspicion.

The next day there was a ministerial visit and they conducted worship services. An elderly pastor took a big piece of chewing tobacco out of his mouth before he started to preach. We were also offered ham, beans, and dried apples to take along on our trip, but our leader, David Klassen, declined the same with the comment that the group was well endowed and that they should give it to the next group that would come as they were poorer. Many felt this was unfortunate, as they were already being assisted by the church (Gemeinde) and felt that they were poor.

From Toronto, we proceeded by rail to Lake Superior and then by ship to Duluth. Here we again entered an immigration house with the knowledge that from now on we were on our own. After we had rested there for a day and a night we boarded a train and rode on to Moorhead. Here we purchased food and coffee and made our own meals.

We were told to purchase food supplies for three days, as we would travel by steamship to the capital city of Winnipeg, and nothing could be purchased en route. I, together with a number of the brethren, went to the baker but he had very little ready. He promised us that in four hours he could bring us bread with his wagon, which we found hard to believe, partially because it was difficult to understand him. But he made it clear to us that the Red River meandered back and forth, so that we would only make very few miles in four hours, and that he would wait for us at a certain point in the river and deliver the bread.

Sure enough, after we had travelled for four hours we suddenly spotted a vehicle on the riverbank, and there was the baker with the bread. I will draw out here the course of our journey how the Red River meanders here and there. The river was so shallow at places that they pulled the ship with pulley and steam. Consequently, the trip took a long time. Finally, with much exertion, patience, and time, we reached our destination, and our joy was great.

We also encountered worries and anxiety. Mr. Hespeler called our leaders, David Klassen and Cornelius Toews, who were our delegates, into his office while the rest of us were to stay patiently on the ship until the next day.

Selecting the Land

The spirit of the Amalekites now stood in our way and had to be battled. This caused a division, such that the Gemeinde divided into two groups, one part favouring the east and one part the west. Our leaders D. Klassen and C. Toews, together with Johan Janzen, Henry B. Friesen, and myself, went along with Hespeler into his office.

Here Hespeler explained that he had no other land for us than the land on the east side of the river. Toews acknowledged this and wanted to go there by ship, about thirty miles upstream. David Klassen was directly opposed to this. Firstly, having immigrated at seventeen years old from Germany (Prussia) to Russia, he said that the land on the east was far too low for raising crops.3 Secondly, as a people, we did not have sufficient means to build the ditches to drain off the water. And thirdly, he did not want to leave the city of Winnipeg until he had a wagon, oxen or horses, and a cow.

Thus it occurred that the two brethren were separated from each other by their differing outlooks and state of mind. When Mr. Hespeler saw that nothing would move the elderly immigrant, he suggested that there was still some land on the Red River. Klassen replied that as delegates they had already reserved a place for the Mennonites. “Yes,” replied the gainsayer, “that land is no longer available.” Now Klassen was cornered.

Some sixteen families remained in Winnipeg, where we acquired two wagons. Finally, when we realized that a division among our sixty-four families was inevitable, we decided that it was highly advisable for us to personally inspect both settlement sites. Since no one besides my brother-in-law Isaac Loewen and myself had already bought horses, we agreed to hitch them to the wagons and to take three other men along in order to investigate the land. These men were Jacob Friesen senior, Franz Froese, and Johan Janzen.

First we drove to the east side, which they [the immigrant families] had reached by travelling thirty miles south by ship and then being taken farther east on two-wheel carts by the half-breeds.4 Here Shantz had already had immigration houses built.5 But no well had been dug, and consequently a murmuring and disputation occurred there as in Numbers 20:13. I myself had to hear how two elderly brothers disputed with each other.

On our way down we met my cousins John and Peter Harms on their way back to Winnipeg. They said they could not exist or survive without water. We drove farther east, where we discovered artesian springs with good water. However, night overcame us before we got there, and so we decided to settle down for the night among a bluff of trees in a spot with some pond water. It should also be noted here that we had brought coffee and kettles with us but not enough cups to drink from.

In Winnipeg we had a well drill constructed for us and so we started to drill here, but the device was too small and we were unable to bore deep enough to strike water. Presently Franz Froese mentioned that here we had potter’s clay and that we should make some pots from which to drink our coffee tomorrow.

“No sooner said than done.” But what happened? With nightfall we were joined by a million observers who did not spare themselves to attack us and bite us without mercy. At the same time they sang without stopping for breath. We had to conceal ourselves with blankets. Initially we were able to alleviate the situation, fighting back with fire and smoke, but this ran out by the time we fell asleep.

By early morning when we awoke the singers (mosquitoes) had thinned out considerably. We made our coffee, ate our breakfast, and again readied ourselves to continue our land inspection. We drove a stretch farther and then returned to Winnipeg. As soon as we arrived there and had more or less given our report as to our experiences, David Klassen and his children, my siblings the Martin Warkentins and the Peter Duecks, the Johan T. Friesens, and several other families prepared to travel and departed for the west side (the West Reserve) in order to establish their future homes there.

Scratching River

After a day’s sojourn we five messengers united ourselves to travel to the west side to also inspect the land there. The entire caravan departed at midday with all our goods and belongings. Early the next morning we were again underway and met the other group, which had driven ten miles on the bank of the Red River, where they overnighted and were now eating breakfast. My mother requested that if I would return to the city I should buy some meat and lard for her.

We now proceeded across country and by evening we arrived at the river, where the horses were unhitched and fed. We were again joined by an enormous swarm of observers, who were not satisfied merely to see what foreigners had come; indeed their biting was their welcome.

We overnighted in this wilderness, and the next morning we looked around to see where we had driven in the dark night; I believe that each one of us had his own thoughts. Again we made coffee and ate breakfast together.

Then we inspected the region and discussed whether the west side would not have an advantage over the east. It seemed that we five individuals were all of the view that this land was more appropriate for grain farming, and also decided to settle here.

A dead tree stood nearby and I took my pencil and wrote on the trunk that our advice would be to settle here, with the following words: “It is good to be here, let us build our homes.” As the grass was luscious, Johan Janzen drew a cow under my writing. We knew that the next day the other caravan, with D. Klassen, carrying their burdens of goods, would arrive, and they would be able to see what our view was in this matter.

On our return journey we took a different route in order to have a better road. First we drove approximately 4 miles southeast towards the small city of Morris and then north to Winnipeg about 40 miles. By the time we returned we had driven 160 miles. Through this exertion we had endeavoured to determine the best option for us.

The proverb “unity makes strength” would be rather appropriate here. This held us five messengers together in our decision.

I will list by name the five who now prepared themselves for the journey and who had allowed themselves to be used as messengers, namely, Jacob Friesen, Franz Froese, Johan Janzen, Isaac Loewen, and Heinrich Ratzlaff. We rushed to ready ourselves and made haste on our journey towards our new homes.

Night overfell us as we were still twelve miles away from the settlement site, and so we had to stay overnight there. My brother Peter Dueck also overnighted with us, as he was on his way to Winnipeg to pick up a load of lumber for building. He told us that when he had left the place where we planned to settle near the river, of which mention has already been made, our mother was very sick and that I would not see her again among the living.

Early the next morning we broke camp and made great haste in order to reach the settlement site, and arrived there at 11 a.m. But alas, mother had died at 10 p.m. the previous evening, almost exactly the hour that brother Peter had given us the news, and so our joy was transformed into sorrow. Instead of the progress of building our new abode, a coffin and grave had to be prepared.

This again confirmed what the preacher states in Ecclesiastes 3. After the funeral the congregation sang together under the open sky, whereupon each and every one returned to his work.

Establishing the Villages

The area was inspected and plans were laid out. First of all, a choice again had to be made: one part went together with David Klassen, namely his children, and their village was to be called Rosenhof; the second part would form Rosenort. Since I had already been inaugurated in Russia as village mayor (Schulz) and had served as the treasurer for the entire trip, I was also appointed as leader in this village of Rosenort. David Klassen was the leader in Rosenhof.

After the selection of lots, we all settled as near as possible to the river, which was called the Scratching River. Our lot fell more or less in the centre of the village, and our neighbours were Franz Wiens, Martin Warkentin, Johan T. Friesen, Peter Dueck, Isaac Loewen, Jacob Toews, Heinrich Friesen, H. Ratzlaff, Johan Janzen, Gerhard Harms, Peter Kroeker, Franz Froese, Klaas Brandt, Johan Harms, and Peter Harms. There was a great hurry to complete the construction of our shelters, as it was almost the end of August, and the lumber for building had to be hauled in from Winnipeg, which was forty miles to drive, and with oxen and wagons at that.

This was no small matter. Nevertheless, brother-in-law Isaac Loewen and I bought ourselves two horses at $300 for the team, and also two oxen, in order that we could go with two wagons. Still, it was almost a week before we returned.

Now we dug a basement and started to build, twenty feet by twenty-six feet, and at the west end a serrai for two horses, two oxen, and two cows. The building was insufficiently covered with paper and was too cold for the winter. The potatoes froze in the cellar and we had to take them up into the dwelling, in which we two couples resided.

In the month of May the brethren started to plow the ground and others brought home the hay that they had mowed the previous September. We also brought in a supply for the winter. This was a completely different environment from what we were used to in Russia, where we were frequently finished with seeding by the beginning of March. Here we were only able to start with seeding at the beginning of May.

Emigration to Nebraska

That winter, many made the decision to move from Manitoba to Nebraska, where it was not regarded as an offence to write us inviting letters describing how nice it was there and in Kansas. When they wrote that they were already seeding, we still had the cold winter and much snow.

Finally Abram Klassen, our minister, decided that he would go to Kansas in May to see how things pleased him in the south. When he returned, a number of us visited him that evening and he related matters to us that were unbelievable. He told us that the Kansas wheat was heading, rye fields were turning colour, and the corn was a foot high.

He then asked his sons how large their grain had grown, which had been sown before he left for Kansas. Diedrich responded, “Go see for yourself.” It was near the house, but dark at night. Mr. Klassen immediately went to see, only to find that the grain was just appearing. When he returned to the room, he hardly knew how to contain himself, and said, “We do not want to stay here.” This made a big impression upon the others who were also minded to move away.

The Claas Wiebes, John Harmses, Peter Harmses, and ourselves wanted to be on our way as soon as possible, and since we and the Peter Harmses were agreed to leave, so it was. The H. Friesens left in May already. On June 4, 1875, we left Manitoba. After ten days we arrived here in DeWitt (Nebraska), where our siblings the Cornelius L. Friesens met us and took us to Heuboden. The Claas Wiebes had arrived earlier, staying with Uncle Isaak Harms in Blumenort. It did not take long until the John Harmses, Peter Brandts, and Peter Buhlers arrived, and then also Peter Barkman (?), the John S. Friesens, and the Jacob Ennses from Blumenort, Manitoba. After Aunt Isaak Harms [Anna (Sawatzky)] passed away, Uncle Harms went to Manitoba to bring the widow Klaas Friesen [Carolina (Plett)] to Nebraska.

When we arrived here on June 14, we had to make a new start all over again. I bought a hog for $3.00 from brother-in-law Jacob Klassen. This was very different from Manitoba, where we paid $7.00 for half a hog, which was no larger than this whole one. After we had visited here one week, my brother-in-law Klassen drove me to Fairbury to buy horses.

After many enquiries, we went to a farmer named Bondi who was eager to sell, and we started with two horses, one gelding three years old and the other five years. He sold them to me for $160, then two cows for $45 together, one buggy, harness, pails, and a brush for $20: a total of $225. Now I went home again.

Then I bought a large wagon from Greeves and some planted corn and wheat from an Englander (American). There were also potatoes and garden vegetables, altogether twenty-five acres for $50. We were happy for we had a harvest in 1875 already.

We faced another problem. Where should we purchase our land? Jacob Klassen had eighty acres available for us, as did Uncle Isaak Harms, both for the same price of $3.50. I went to Fairbury, bought lumber, and drove with it to brother-in-law Klassen’s eighty acres. But the next day Johan Harms, together with his father, came to persuade us in this manner: If we would not move to the Harms village, then they would return to Manitoba – his wife had said she would not stay if [we would not move there]. Seldom was there such an advantageous offer; we could have the best eighty acres in that area. So the lumber was again loaded and taken to the Harms village, which later became Blumenort.

Conclusion

We shared joys and sorrows here from 1875 until December 16, 1881, when, after a fourteen-day illness, my wife died, and I remained sick and almost forsaken in bed. Our baby was nine months of age. The little Sara had to leave to be cared for by strangers, namely the Jacob Fasts. Grief and pain were so difficult to bear that I hardly knew what to do. My mother-in-law was with me, but what did it help? When she saw me weeping with sorrow, she also wept. When I could control myself, my little four-year-old Nettie came to me, reached out her hand to me, and said, “My loving mother has died,” which broke my heart, and then we both cried.

- This memoir was previously published in Delbert F. Plett, ed., Profile of the Mennonite Kleine Gemeinde, 1874, Mennonite Kleine Gemeinde Historical Series, vol. 4 (Steinbach, MB: DFP Publications, 1987), 187–92. A copy of Ratzlaff’s original German manuscript and another English translation can be found in vol. 6527, file 24, Delbert Plett Collection, Mennonite Heritage Archives, Winnipeg. ↩︎

- People from the village of Heuboden. ↩︎

- David Klassen served as a delegate on the scouting trip of 1873. He was one of the few immigrants who experienced both the immigration from Prussia to imperial Russia (1833) and the immigration from imperial Russia to Canada. ↩︎

- This is a reference to Métis ox cart drivers. ↩︎

- Jacob Y. Shantz, a Mennonite from Ontario, was a promoter of Mennonite immigration to Manitoba. ↩︎