Colombia and Peru: A New Home for Low German Mennonites

Kennert Giesbrecht

Establishing new colonies is nothing new to Low German (LG) Mennonites. Since 2000, more than one hundred new colonies have been founded in Latin America. The word “colony” is used for a LG Mennonite community if it has a parcel of land and it has its own independent church and colony leadership. For the church it’s usually an Aeltester and several ministers and one deacon; for the colony it’s at least two Vorsteher (administrators), who represent the colony in all dealings with local and national governments. A fully established colony would also have a Dorfschulze (mayor) in each village, and a Brandaeltester, who supervises the storm and fire insurance for all the members of the community.

Most of these new colonies were established in countries where LG Mennonites are well-known to the general population. But in the early 2010s, Mennonites started to explore new terrain. LG colony Mennonites from Bolivia, Mexico, and Belize investigated settling in Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Angola, Suriname, and yes, at one point even the Russian Federation. Two of these countries have become new homes for LG Mennonites: Peru and Colombia.

Thanks to the support of the D. F. Plett Historical Research Foundation, in June 2024 I was able to visit all ten colonies in these hotspots, four in Colombia and six in Peru. All of these colonies were established over the last ten years, some as recently as 2022.

In the Eastern Lowlands of Colombia

The Mennonite settlements in these two countries are very different. The colonies in Colombia were established by LG Mennonites primarily from northern Mexico. With the depletion of groundwater in the desert regions of Chihuahua, they were looking for a region with enough rainfall to cover their farming needs. The lowlands of eastern Colombia, Los Llanos, seemed to be the perfect fit. They came with strong financial backing from the wealth accumulated through farming over the last couple of decades. In a very short period, they were able to acquire large tracts of land in Meta province, not too far from a small city called Puerto Gaitán.

Currently there are four colonies in Meta province: Liviney, Australia, Pajuil, and San Jorge. As the land they bought had been mainly used for cattle ranching prior to their arrival, there was no need to clear forests. Some shrubs and trees were removed, and because of the deficiency of calcium, Mennonite farmers had to add it to the soil. They have quickly developed the region into an agricultural stronghold – on an estimated 35,000 hectares of land, Mennonites have seeded rice, corn, and soybeans. But that’s not nearly all the land they possess. Klaas Wall, one of the pioneers of the Liviney Colony from Nueva Holanda, Chihuahua, estimates that LG Mennonites now own more than 100,000 hectares and will likely acquire more in the near future. According to Mennonites residing there, “Everyone around us seems to be wanting to sell their land to us.”

It is estimated that 1,100 LG Mennonites call Colombia home. Since their arrival, more than one hundred Mennonite children have been born in the country. They are automatically citizens of the country, whereas immigrants must go through a lengthy and costly documentation process. Most likely, the number of LG Mennonites will increase dramatically over the next few years.

Why are they moving? In the case of Klaas Wall, he was simply tired of the dust storms and the challenges brought by the depleting groundwater levels in northeastern Mexico. In 2014, when he visited the Los Llanos region for the first time, Wall had the feeling this would be a great place to build a new home. Almost twenty years earlier, he had made a similar choice, moving from Cuauhtémoc to Nueva Holanda. He’s not the only LG Mennonite to participate in more than one major migration in his lifetime. And who knows, this might not be their last move. But according to Wall, they are in Colombia to stay: “This is not about exploiting a region and sending the money we’re making somewhere else, as some of the media is trying to claim. We want this to be our home.”

When driving through and between the colonies it is hard to comprehend that these settlements are a mere six or seven years old. The amount of work and money that has been invested into developing homesteads, roads, businesses, and, of course, their farms is hard to describe. It needs to be seen to be believed.

Most inhabitants of these colonies are descendants of the 1922–1924 migration from Canada to Mexico. Their forebears made a daring move into a strange and new country. They were the first LG Mennonites to migrate to Latin America. Others soon followed. And ever since that historic migration, LG Mennonites have continued to spread out across Mexico, into Belize, Bolivia, Argentina, Paraguay, and more recently to Colombia and Peru. And don’t get me started on the internal migrations that have happened within these countries. Mexico alone has more than 60 Mennonite colonies today; Bolivia has over 130 colonies.

And while their forebears searched for a country that would officially recognize their special privileges, the current migrants don’t seem to care too much about this. Yes, they still want their religious freedoms and their own schools in German and Low German. And no, they don’t want their young men and women to serve in the military, but none of these countries have mandatory military service and all guarantee religious freedom. So having an official document recognizing these rights doesn’t seem to be of great concern.

One thing is for sure, these LG Mennonites in Colombia are writing history. It is a new story, a new chapter in an already rich history of migrations dating back centuries.

In the Land of the Incas

When asked if they are optimistic and excited about the move to Peru, Old Colony minister Isaac Dyck replies without any hesitation: “We have no choice, really! We sold everything in Salamanca, Mexico. Now it’s all about the here and now. This is our new home. We’re looking forward, not backward.”

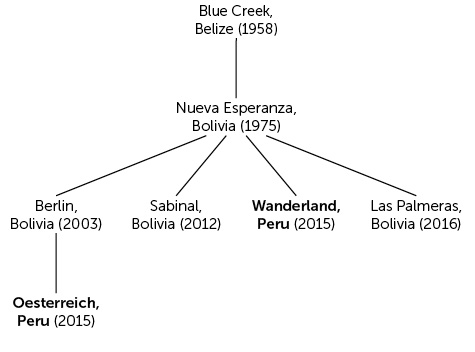

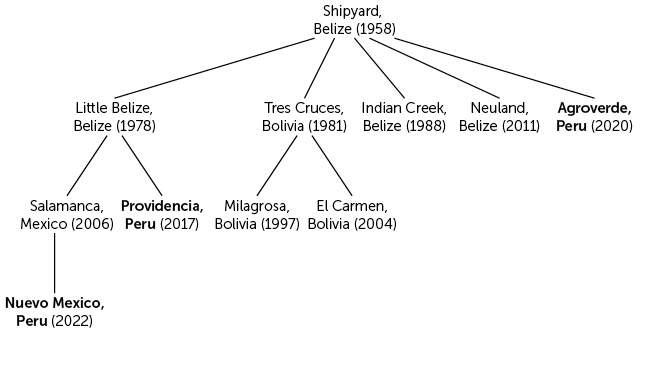

That seems to be the general attitude in all six (yes, six!) newly established Mennonite colonies in the Peruvian Amazon. All but one have strong Belizean ties. Their ancestors would have been part of the large migration from Mexico to British Honduras (now Belize) in 1958. From there on, their paths went separate ways. Some moved to Bolivia in the 1970s, others back to Mexico in the early 2000s.

In 2006, the Peruvian ambassador to Canada, Guillermo Russo, made a plea for LG Mennonites to settle in his country to farm. He had seen and heard of the progress made by Mennonites in Paraguay, Bolivia, Belize, and Mexico. Russo also met with several people from the local LG Mennonite community in Winnipeg. He commented at the time: “We need farmers, we need people who can and want to produce in large quantities. And everywhere I see Mennonites, I see progress. We have the land, but we need farmers, and the Mennonites would be just the right people.”

Not long after that conversation, a group of Bolivian Mennonite farmers from progressive colonies visited and explored regions of Peru. However, they were not impressed with the land. They had hoped to find large tracts of unused land, but instead found only smaller plots. It took nearly a decade for Russo’s vision to come to fruition.

Three colonies are close to the city of Pucallpa, often called “the gateway to the jungle”: Masisea, Agroverde, and New Mexico. Pucallpa, a city of half a million people, is connected to the rest of the country by only one paved road. There are also daily flights to the capital city of Lima and other cities in the country. If you want to go east, north, or south from Pucallpa, you must take a boat or ship. The main route is the Ucayali River. Meandering northeast, it eventually converges with the mighty Amazon. Many smaller tributaries feed into the Ucayali, a network of rivers and creeks so vast one can only grasp it fully when travelling by boat or flying over it by plane.

The three other colonies (Wanderland, Oesterreich, and Providencia) lie roughly 375 kilometres downstream, near a town called Tierra Blanca. To visit this second group of colonies one must travel by boat for more than twenty hours. No roads connect these colonies to the rest of the world.

Aside from Masisea Colony, the other five colonies have strong ties to the Mennonites who left Durango and Chihuahua, Mexico, to find a new home in Belize in 1958. In Belize they founded the colonies of Shipyard and Blue Creek. Over the course of more than sixty-five years, those two colonies have founded numerous other colonies – some in Belize, others on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, and several in Bolivia.

In need of more farmland, Mennonites from Nueva Esperanza, Berlin, and El Cerro (in Bolivia), Shipyard and Little Belize (in Belize), and Salamanca (Mexico) explored settlement options in the Peruvian Amazon and eventually acquired land in that region to start up new colonies. Although for most settlers the need for cheap farmland drove this adventurous migration, for some in Bolivia it was political uncertainty or instability that led them to look for another country. And for many, especially in Belize, it was also an attempt to move away from the influence of modern society. As Johan Bueckert explains: “Our young people in the colonies more often than not carried a smartphone around. Even though most would have hidden it from parents or other adults, everyone knew they had it. Smartphones and other devices were just so easily accessible. The connection to the internet was readily available. And many parents just felt they could protect their children better if they lived in a more remote region of this world.”

The migration to Peru has not been easy. Acquiring land has been rather difficult. In most regions in the Ucayali province, Mennonites could only buy smaller parcels of land, which meant the community often had to buy land from more than a hundred different landowners. The amount of paperwork required to complete a transfer of landownership was often stressful. And under the close watch of environmental groups, obtaining permits for clearing the land has become increasingly difficult. And even though only a low percentage of the forest cleared in the Peruvian Amazon region has been done by Mennonites, for their small farms, they have been the focus of critiques and attacks by many environmental organizations and Indigenous groups.

Today approximately 2,500 Mennonites call Peru home. Hundreds have already been born in this remote region. Most families will own 10 to 20 hectares. A few might own up to 50 hectares. Many of the farmers have cleared no more than half of the forest on their land. They are small mixed farmers. Most have chickens, maybe a cow and a pig. All use horses as their main mode of transportation. In the rainy season they will cultivate rice, and in the drier season they will either plant corn or soybeans. Each colony consists of two, three, or more villages. Each colony has its own church leadership and secular administrators.

On their newly established farmsteads, Mennonites have fruit orchards and vegetable gardens. It is hard to find a more self-sustaining group of people than these Mennonite settlers in the remote Peruvian Amazon, the land the Incas once occupied and called theirs. Yet at this point, many families still struggle to survive. “It hasn’t been easy, but if we look around and see what we have accomplished in less than seven years, we feel hopeful and optimistic,” says Bernhard Friesen, one of the Vorsteher and an early settler of Wanderland Colony. And if anybody can talk about hardship, it’s Friesen. In 2022, his wife died giving birth to their tenth child. Since then he has remarried, and the blended family now has fourteen children.

Stories like this show the grit and determination of the Mennonite settlers in Peru. There’s no giving up. There’s no sitting around and dwelling on what has happened. It’s always about the here and now and the future.

Kennert Giesbrecht has been a Plett Foundation board member for twenty years. Until his recent retirement, he was the editor of the newspaper Die Mennonitische Post.