Eleven Settler Stories That Matter: An Environmental History of the 1870s Migration to Manitoba

Royden Loewen

I begin with a meditation on the title of this essay.1 Why eleven stories? Why not ten or twelve or three or seven? I learned about the number eleven from my daughter Rebecca, who, some years ago, was directed to an Indigenous healing circle. It was said that eleven is an inclusive number: it beckons you to be open, to learn. Numerologists say that eleven “is intuitive . . . , channeling its knowledge and meaning from a spiritual source,” using the “gift of awareness to deliver . . . truths that encourage humanity.”2 Now ten and twelve are definitive, hard numbers, a dozen or a decimal: there are twelve disciples, twelve delegates, twelve by three sections in a township; and ten is the very foundation of the authoritative metric system. By telling eleven stories I want to signal that they carry truth, but with an inclusive number, it means that I invite you to consider your own stories. These eleven stories arise, as you will tell, from a lifetime of writing; they are my eleven, in a sense. You will have your own.

The second word, settler, is less abstract; it’s factual. It’s a word used in Treaty One: “it is the desire of Her Majesty to open up to settlement and immigration a tract of country,” it says.3 And it’s also a word we used as Mennonites, aun siedle or aun siedlen, the verb, Siedler and Siedlung, the animate and inanimate nouns. In this sense our forebears were much less “pioneers,” less innovators, than they were settlers, transplanters, folks turning fluidity into permanence, grasslands into village and field. And they displaced Indigenous people in the process and there can be no celebration without an acknowledgement that flesh and blood people once called our villages, our city, our fields as their home.

The third and fourth words, stories and matter, are the easiest. As historians, we create narratives and, of course, those that “matter,” that set trajectories, that explain the present day, that tell us who we are. And today what matters to me is that we have been a people of the land. And that story is environmental history. A lens that focuses on “society’s interaction with nature” to cite Donald Worster’s rudimentary definition.4 It’s at the core of the settlement of Mennonites in Manitoba 150 years ago. Of course, it’s not only that; it’s instructive. It says we must link society and environment or see a myopic story; settler farmers are never divorced from nature. We also know it’s a varied story: it is at once “romantic,” in which nature is the gold standard of everything – pristine, idyllic, bucolic – and “pragmatic,” in which work in nature is the very basis of economic survival and social status. And it’s more varied than that: there are, in fact, many ways of telling this story. One is to juxtapose the social and nature, as I set out to do here. Acknowledging that in history there is dialectical relationship, the social and nature, one always affecting the other. Consider this, then, eleven ways of constructing an environmental history of the migration of the Mennonites to Manitoba.

Bird Flying Down

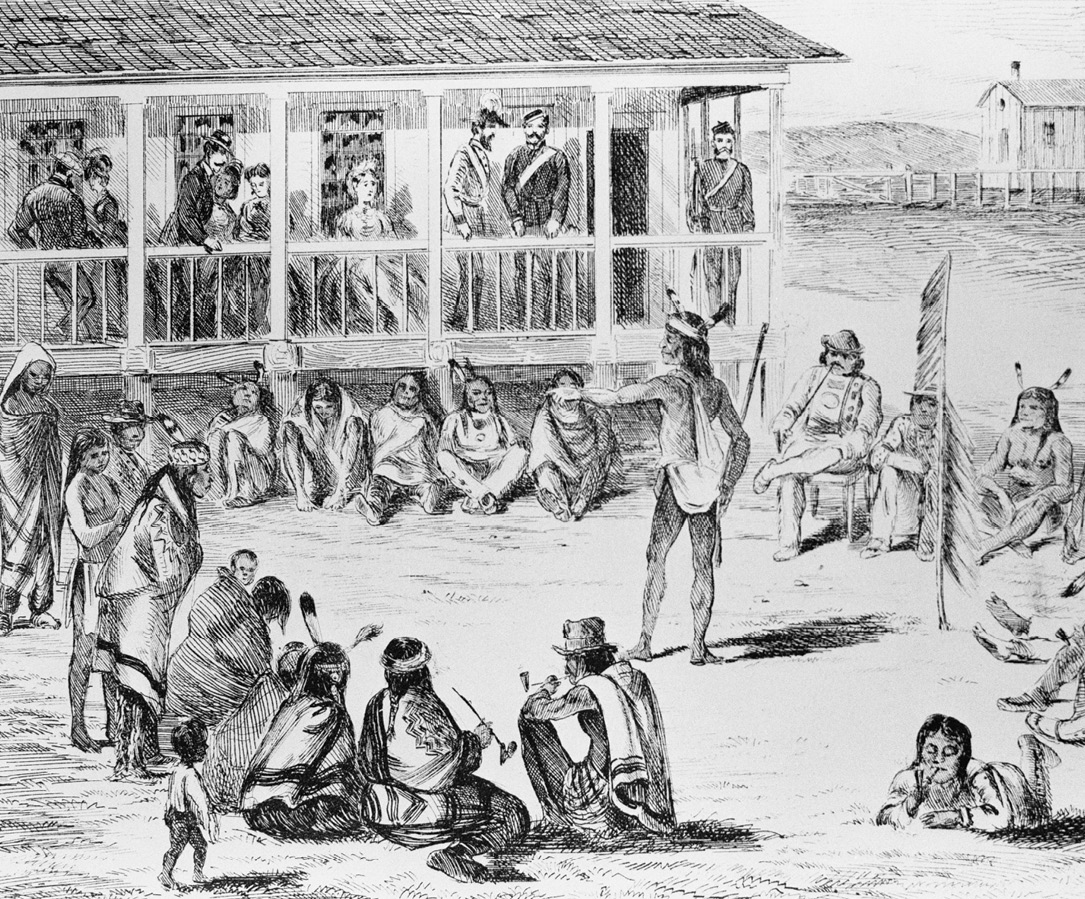

The first story is one I told in my Blumenort book forty years ago, of Chief Ke-we-tay-ash, Flying Round, the fifth Indigenous leader to put his X to Treaty One, one of four chiefs linked to land along the Roseau River, of the Ojibway people, the Anishinaabe. On August 3, 1871, he gathered with thousands of his kinfolk at Lower Fort Garry, Stone Fort, an encampment, sitting with Lieutenant-Governor Archibald and his entourage. It was a social event. But at the heart of it all was land, two vastly differing views. Two years earlier, in 1869, Chief Ke-we-tay-ash had asked the Canadian government to recognize his people’s land. Ke-we-tay-ash said it was “bounded by . . . the Government (Dawson) Road on the north, Pembina Mountain on the west, White Mouth River on the east, and the American boundary on the south”:5 3.5 million acres. In 1871, at Stone Fort, he had his answer from Archibald: “Her Majesty the Queen hereby agrees and undertakes to lay aside and reserve for the sole and exclusive use of the Indians . . . belonging to the band of which . . . Na-sha-ke-penais, Na-na-wa-nanan, Ke-we-tayash and Wa-ko-wush are the Chiefs, so much land on the Roseau River as will furnish one hundred and sixty acres for each family of five, or in that proportion for larger or smaller families, beginning from the mouth of the river.”6 Ke-we-tay-ash wanted 3.5 million acres; he settled for 5,496.32 acres.

This story references a second Roseau River signator to Treaty One, Chief Wa-ko-wush, or Whip-poor-will. He appears in Jonathan Dyck’s recent graphic depiction of Indigenous leader Dave Scott’s rendition of “The Secret Treaty,” published by Canadian Mennonite in February. In this account Wa-ko-wush “saw that the Mennonites had received the land they were promised but his people had not. He saw the situation was unbalanced, so he petitioned the Indian agent,” but was told, “Shut up! And stay in your reserve.”7 Roseau River’s history is illuminated when we realize that the East and West Reserves were surveyed shortly after 1871; Roseau River waited till the mid-1880s, and not until 2011 were they compensated for all the lands they were promised. Ke-we-tay-ash and Wa-ko-wush were brothers, husbands, grandfathers, people of emotion and heart. They loved the lands of the southeast. Environmental history speaks of justice.

Boy of River, Field, and Forest

The second story is that of a boy, age twelve, the son of settlers. He is David L. Plett, my great-grandfather, who died a year before I was born. He arrived as a settler at age twelve in 1875 and wrote about the migration. He described the route in detail: “From Odessa we went by train through Prussia, Austria, and Germany to the city of Hamburg. How many times we changed trains I don’t remember.” He listed the people: his brother-in-law picking them up at the landing site, his parents, a neighbour. But it’s not just about machines and people. David recalled how they “sailed down the Elbe into the North Sea to England,” how they “crossed England,” entered the “huge ocean,” journeyed “along the Red River,” and then reached the East Reserve.8

As a twelve-year-old he is frank: “it did not look very appealing here,” the crops from last year consumed by grasshoppers. At Blumenhof, just east of Blumenort, “our parents built a homestead. A house and a barn. . . . Pasture was broken. The lumber for the house had to be hauled from Winnipeg. . . . Because I was not quite 12 at that time, I cannot remember everything exactly. . . . [But] the firewood for the first winter was all taken out of the poplar tree bush. . . . This I remember well. . . . All travelling was done by oxen. For winter Father bought another horse. Then it was easier to travel to church, with two horses.”9 David, the child, relates to nature: its seas and rivers offer the route, but it is threatened by waves; its land is sown but hurt by grasshoppers; its forests offer warmth, but in response to startling cold; its animals – the oxen and the horses – cross distances, vast by comparison to Ukraine’s. There are no bishops, delegates, deputy ministers, school trustees in this boyhood narrative. It is raw and primordial.

Comfort, Need, and Nourishment

The third story is that of Elisabeth (Janzen) Loewen (b. 1843) of Rosenort, Scratching River Reserve. She is my great-great-grandmother, the wife of Isaac W. Loewen, the village mayor. A great deal of social pathos intertwines her story. Elisabeth is separated from her widowed mother, Sara (Siemens) Janzen of Jefferson County, Nebraska, who writes in an October 1874 letter: “Oh, how difficult it is for me that we have to live so far apart from you. Can it be no other way?” Many letters link Nebraska and Manitoba, but also many cross the Red River, Yantsied to Yantsied. Some are by Grandma Elisabeth from Scratching River Reserve to her brother Johann on the East Reserve. They reflect her own mother’s immutable sense of social belonging. A November 1877 letter enquires about the Warkentins at Blumenhof, greets Uncle Peter at Neuanlage, and pleads for more letters from her sister-in-law, exclaiming, “Write me as often as you have time . . . you do write so well!”10 Letters by neighbours describe Elisabeth herself. One from February 1877 signed “Mrs. Klaas Brandt” reaches out to family in Nebraska, reporting that Elisabeth is ill and “could stand some comforting.”11 A June 1877 letter by Elisabeth’s husband, Isaac, is an urgent request to brother Peter on the East Reserve for a maid, emphasizing, “we must have a girl!”12

But within all this social cacophony is nature. Elisabeth is a child of the land. Her well-being is the farm and the garden. In another letter by Isaac to brother Peter, she adds her own postscript, a note of importance: “Now I will report that we have slaughtered two good pigs and also slaughtered some 35 chickens, also of good quality.” Also, the “potatoes . . . yielded very badly, only 10 bushels and of those many were green.” But “wheat we received 500 bushels from 35 acres, however, there was much smut in it; barley we received 115 bushels from 4 acres.”13

Here was a settler who knew her extended network of friends, but also the economic state of the farm, the yield it extracted from the soil. It was at the root of the family’s well-being.

“And We Do Not Want to Leave”

The fourth story is that of Elisabeth (Rempel) Reimer, the matriarch of the Steinbach Reimers. There’s lots of social history here. Elisabeth is the wife of Abraham F. Reimer, nicknamed “Foula Raema,” Lazy Reimer, so much so that he has time to write down what everyone else in the village does.14 A 1955 family history says of Abraham, “As is the case with many so-called men of knowledge, he too did not always land up on a green twig.”15 Elisabeth’s daughter Margaretha is said to have suffered as a young girl because her mother had to be the breadwinner, “often called away from home on business . . . tailoring men’s suits, making men’s caps with patent leather peaks, and even making hoop skirts for the nobility.”16 But Elisabeth was also the matriarch. In 1870, for example, she was at the bedside of all five Reimer baby deliveries, including the birth by now-eighteen-year-old daughter Margaretha of her first-born, yet another Elisabeth, and, in full disclosure, my great-grandmother.

The most frequently told stories of Elisabeth relate to Manitoba’s climate, the platform of a narrative that rendered her a most strong-willed woman. In a less often told story she allows a group of inebriated men to shelter in her house during a snowstorm. Her husband is nowhere in this story. She simply orders the men to lie down on the kitchen floor and sits up all night watching them, making sure they remained orderly.

An even more consequential story appears in a 1935 history of Steinbach, again from the first years of Mennonites in Manitoba. It comes on the heels of their first taste of Manitoba’s severe winter, of starving cattle nibbling at frozen grass, then grasshoppers, a terribly wet spring, an early frost. The men are restless, dozens of families are moving south to Kansas and Nebraska. Steinbach’s most prominent business owners, Elisabeth’s son Klaas Reimer, merchant, and son-in-law, Abram S. Friesen, windmill owner, speak out at a Sunday afternoon Reimer clan meeting. It’s time to leave Manitoba for greener pastures in the US. Elisabeth leans into the conversation; she’s made up her mind: “This we do not want to do, for the dear Lord has heard my prayers; He has protected us on our journey here. And we do not want to leave. Instead we want to remain faithful . . . in our calling and not become discouraged. I have faith in God that He will bless us and that we will have our bread.” The 1935 story concludes: “her children were obedient, and became successful.”17 Nature will not dominate where the Divine is trusted.

“Come Watch This Spider”

The fifth story is about Aeltester Gerhard Wiebe, writing his memoir in 1898, now elderly, recalling the migration of Mennonites from imperial Russia in the 1870s.18 The whole book is about betrayal in imperial Russia and epic relocation, a re-enactment of the children of Israel fleeing the clutches of Egypt, a story of “how the Lord God led us out of Russia,” how “God divided the waters.”19 Gerhard is the modern-day Moses, guiding his people to Manitoba. There is much that is grandiose: palaces in Yalta, rooms “much larger . . . next to ours,” titles of “Your Excellency” and “His Majesty,” allusions to treachery, a 200,000-ruble debt, two dozen stranded ships, a sweeping history from Emperor Constantine to Peter Waldo, of cosmic King of Kings and scheming Satan, of disappointing fellow Mennonite churches, the Kleine Gemeinde dazzled by money, the Ontario Old Mennonites stingy on cutting interest on borrowed money.20

In the midst of all of this is epiphany. And it comes from a lowly creature embedded in nature: a spider spinning a web on a beam in the ceiling of Wiebe’s house in Bergthal colony. The spider sends a divine message: a modernizing Russian empire cannot be trusted. It appears the day gullible Mennonite teachers visit Aeltester Wiebe coveting a “pleasing” modern school curriculum offered by one Baron von Korff. Wiebe fumbles in ambivalence but then he sees the spider and knows the Lord has spoken: “Come and watch this spider; that shall be my answer. She has spun her threads everywhere, and now she spins her web. . . . A fly . . . gets caught and hangs in the web. . . . The spider . . . kills the fly. This man [von Korff] . . . spins the fine threads for catching and then he will . . . capture us.”21 The spider brings illumination, the old faith of simplicity stands, the new secular curriculum is rejected. The Bergthalers are the stalwart ones, the accommodating Mennonites have “become sleepy.”22 The secular curriculum is the web that will snare those “sleepy” Mennonites, undermining their commitment to absolute pacifism, and they will compromise and stay in the old homeland. The revelation from the spider propels the three-thousand-person Bergthal Mennonite community to join the great emigration to “America.”

This spider has not survived the annals of anthropocentric Mennonite history. If an agent from the insect world appears, it’s the ubiquitous mosquito or the debilitating grasshopper.23 The lowly spider, that messenger from God in nature, has been overlooked.

“Deep Snow . . . Time to Think”

A sixth story is from a memoir by farmer Peter Elias. In it, an elderly Elias reflects on his first two generations in western Canada. At its heart is a political event of grave consequence: news in 1871 of changes to the government’s military service laws that threatened the faith tradition of Mennonites. The event sparks the emigration fever. Another government act, this one from Canada, offers a Mennonite rescue. As Elias puts it, “God sent a man by the name of Wilhelm Hespeler from America, sent by the government to recruit immigrants and offer them freedom of religion. Was this not a way out for distressed souls?”24

This is the germ of the book, a political moment, and there’s enough ecclesial musings in it to satisfy the church historian, but Elias’s account is bookended by environmental history. It begins with his childhood in the old homeland – a page on school, then one each on butchering pigs, making hay, silkworms, grain harvest, field work, and harnessing the wind. There is much in the book about moving, but always with land in mind. There is the twelve-man land-scouting delegation. Then settlement on the East Reserve, with “a cow . . . probably our most urgent need,” then Peter and brother Jacob are off to the fir forest for lumber, while wife and kids take the “oxen and wagon” to gather wood.25 Then, when it becomes clear that the Old Colony Eliases are on the wrong reserve, their kin all settling the West Reserve, they abandon the just-begun homestead and now another round of engagement with the natural world begins: the crossing of the steep-banked Red River, sleeping out in the open, grazing their oxen on the grassland. Then the imperatives of winter: a rush to put up hay one more time, harvesting lumber for the family’s semlin, braiding tall grass and manure for animals’ serai, and once more scoring enough firewood for the harsh Canadian winter, made more difficult by a massive snowfall in October. As Elias puts it, this “deep layer of snow [gave] us plenty of time to think about when spring might come.”26

A generation later, according to a series of letters appended to the book, all penned to relatives back in the Russian empire, Elias has adapted to Canada, especially to its climate. A lengthy April 1897 letter, for example, puts Prairie Canada’s winter at the heart of the agricultural challenge: “We are busy with the spring seeding,” late by imperial Russian standards, and while the wheat planting is completed, the soil is still too cold for the oats and barley.27 In other letters he is equally fixated on weather, but now celebrates: in 1900 there’s a garden of “fruit trees: plums, cherries, gooseberries, currants,” and high-yielding watermelons. And there’s a bumper crop: “652 bushels of wheat from 16 dessiatin,” and equally rich yields of oats and barley.28 It’s the record of a “smaller farmer,” he writes, but one fully conditioned to a new environment.

“Frost on the Window”

The next five stories are ones I have not written about before. The seventh is that of Maria (Stoesz) Klassen, born in 1823 in Chortitza, raised in Bergthal colony. It appears in my edited diary collection From the Inside Out, but is one I have not mused about before.

Maria is the sister to well-known Aeltester David Stoesz of the East Reserve, married to Johann Klassen. Her biography offers great social history. It includes an 1863 letter from prodigal brother Peter while still in the Old Homeland: he has escaped Bergthal colony for a new settlement in Alt Samara, tired of being a “pawn, sheepishly following the flock.” He scolds Maria, irony oozing, calling Bergthal Babylonian, and crows, “I am quite fortunate here, for I am free. . . . The people here are content and morally good. . . . But enough of politics.”29 Perhaps Maria was tied down. Settling in Ebenfeld, East Reserve, she bore sixteen children; fifteen survived to adulthood, and twelve were girls, begetting the Klassens’ nickname, “the family that had the 12 girls.”30 A diary excerpt from 1887 shows Maria as a post-middle-aged woman, sixty-four, with three girls – Sara, Elisabeth (Lisa), and Judith (Ida) – still at home. Her sons-in-law – Penner, Kehler, Neufeld – help out from time to time; her married daughters – “our Kehlers,” “our Friesens,” “our Mrs. Krahn” – visit regularly. Her married sons are known by their first names, Jakob, Martin, Johann. Her social network extends to nearby Bergthaler villages – Schoenthal, Reichenbach, Bergthal, Blumengard – but also to the West Reserve, where five of the twelve girls eventually make their home.31 If this is some form of Babylon, as brother Peter knew it, she doesn’t let on.

Indeed, intersection with nature infuses the diary. Farm produce is marketed constantly: on the first day of the diary, September 24, Ida accompanies Father to the store in Schoenfeld with four dozen eggs and barters for shoes, gas, and kerchiefs; on the 27th, Father is off to the mill with ten bags of barley; on November 4 he leaves for Winnipeg at 5 a.m. with fourteen bags of flour; on the 7th they go to Steinbach with twenty pounds of butter; on the 9th it’s back to Winnipeg, now an overnight trip, with wheat and a bag of onions, and with daughter Lisa. But the environment is more than the produce of nature. It’s there every day. For brother Peter it had been a life “too routine and unbearable.”32 But for Maria it’s groundedness. Some entries seem gratuitous: September 25 the weather is “fine,” on the 26th it’s “gloomy.” But weather always colours events: on Wednesday, September 28, when “Father, Lisa, Ida and Penner” are called to help thresh at Reichenbach, Maria notes that “it was very hot both days,” and when Father leaves for Winnipeg at 5 a.m. on November 4, “it was cold; there was frost on the windows.” Of course the myriad weather-related entries are never only issues of comfort and discomfort, but of work commensurate with the seasons. The “very hot” days of late September end the harvest time with clear command; the “frost on the windows” just a week later, when Father heads to Winnipeg with wheat, announce a seasonal shift from operation to marketing.33

“Flat, Black Earth”

The eighth is a story I wish I had cited in Mennonite Farmers, one taken from the Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society publication The Outsiders’ Gaze. I do cite J. W. Down, immigration agent, outlining steps of breaking “beautiful rich black soil,” Henry J. van Dyke, Princeton-educated poet and clergyman, speaking about the “wetness of the land,” Father Jean-Théobald Bitsche, scolding Mennonites for being laissez-faire on weeds, and W. Fraser Rae, Scottish travel writer, praising Mennonites for not burning straw or dumping manure into waterways.34 All of these point to environmental history.

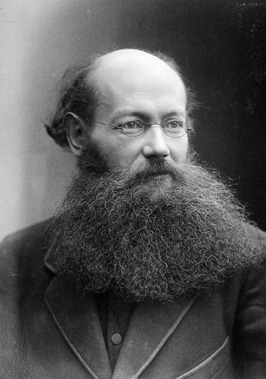

Upon reflection, I might have focused singularly on the most notable of the contributors, Prince Peter Kropotkin, the famed anarchist, who travelled across Canada in 1896 and visited the West Reserve. He loved this land, resembling aspects of the vast Russian empire, and approaching southeastern Manitoba he observed “boundless low prairies”: it was like “entering the low ‘black-earth’ prairies . . . at the foot of the Urals. . . . Same soil, same desiccating lakes, same character of climate, . . . same lacustrine origin.” And then south of Winnipeg, here was “a ‘fat black-earth,’ as our peasants would say, and no trees or shrubs for miles around. Only a glorious sunset to admire.”35

But it is what Kropotkin says that the Mennonites did with this land that is significant. They are “born in such surroundings,” they feel the “poetry of the Steppe.”36 They produce grain commercially, but live in villages, “surrounded by young trees,” their yards abutting on “manured land,” their cattle grazing “a large common,” and “the fields, divided into strips allotted to each family in proportion to its working capacities.”37 They are self-sufficient, peaceful agrarian anarchists, taking nothing from the state, living under the “illusion . . . that if a farmer has the gift to move the hearts of his hearers, he may do it,” claiming the mantle a preacher.38 If Mennonites do leave the village for the socially debilitating quarter section, the “chief motive” is not capitalistic profit, but freedom “from control of the ‘elders.’”39 The natural environment of the prairies allows for village life, “a system of partial communism and passive resistance to the State.”40 Yet, sadly, the homestead system encourages the bonanza farmers that rape the land. The system has “shattered many traditions of old,” undermining “well-being and means to attain it.”41 And then Kropotkin muses, “What would be” Europe “if one-tenth part only of the energy that has been spent conquering wild lands in Canada had been given the land” of Europe? Social justice in Europe might have mitigated the need for colonialism. And he sighs, for he sees on the Manitoba steppe nascent “social conditions . . . [that] drive [the peasants] from the lands,” horrible “land monopolies.”42 The rural environment has the potential to heal; greed and power divide and dispossess.

“Something for the Farmer”

The nineth and tenth stories come from my reading of the 1880s issues of Die Mennonitische Rundschau over the last year or so for my Transnational Flows of Agricultural History (TFOAK) project. The first part of TFOAK focuses on settler knowledges. The letters from Manitoba are remarkable in that two-thirds of their content relate to nothing but the environment. We learn a great deal about knowledge formation on the Manitoba grassland. I share two outlier letters to argue that even when nature seems benign, it’s political, cultural, and constructed.

The first of these stories is by farmer Peter Wiens of Reinland, West Reserve, from April 1882. It’s an unusual submission, a rare article under its own heading, albeit the somewhat underwhelming “Something for the Farmer.” It proposes five principles of agriculture.43 Thus it’s environmental in focus at get-go. Consider an initial reading and then ponder the process by which such environmental interaction occurs. Here are Wiens’s five steps: undertake “early” seed bed preparation by plow and harrow, producing “good soil” for fruitful rooting; eradicate weeds, but in such a way that “seeds are not damaged”; plant “all sorts of seeds . . . as one doesn’t know what will prosper or what the price will be”; keep “all kinds of animals”; fallow 20 percent of the land each year, plowing and harrowing, but not before “it goes to weeds.” Of course, as a good Mennonite, Wiens concludes that this “all depends on the Lord’s blessing”; the farmer’s duty is to “work the land well” and then accept the outcome as divinely appointed.

But aside from the obvious, what is significant about this bland “Something for the Farmer”? First we raise the question of provenance: from where did Wiens obtain this recipe? Well, turn to pages 2 and 3 of the Rundschau and there’s a vast field of knowledge, an invitation to think environmentally: myriad pieces translated into German from English, some from passing non-Mennonite officials, some from US Department of Agriculture reports, some from the English-language American Agriculturist. Some stem from a transnational world of agricultural knowledge, European in origin. In the year before and after Wiens’s article there are reports of science from Germany and from Russia. One from 1883 compares the “practical” American farmer,” always asking “how . . . one might better work the soil,” to farmers in Russia, where the German settler “farms so mindlessly, without considering the endpoint,” unable to fathom a seven-field crop rotation or artificial fertilizers.44 Another submission from 1885 asks, “Black Fallow or Green Fallow?,” the writer identifying as a “practical farmer from Russia,” reporting an on-farm experiment meant to “advance[e] . . . an enlightened agriculture,” showing the limitations of endlessly cultivated black fallow and the astonishing promise of green fallow and plow downs, coupled with grazing sheep.45

Are these the sources for Wiens’s five-step “Something for the Farmer?” A close reading suggests that Wiens wasn’t reading these pieces, but was reacting to the specifics of Manitoba’s climate, the North American market, and Mennonites’ short agricultural history. First, a much shorter and more intense growing season than Ukraine’s demanded “early” seeding, ensuring crops flowered before July’s heat and matured before late October’s snow. Second, there’s the seven-year itch, weeds catching up to farmers using heavy manure on lands broken in 1875. Third, the admonition to consider “all kinds of crops” and animals confronts the prairie obsession with monocrop wheat production. And fourth, the call for fallowing “until weeds pressure” is significant in that fallowing is not linked to moisture preservation, as it was in Ukraine. What is significant about this “Something for the Farmer” is that it is clearly more than five steps to successful farming. It’s a testimony to seven years of meditating on Manitoba’s climate.

“Silent Guests from the Woods”

The tenth story is a nameless one, an anonymous writer describing people without a name, also published in the Mennonitische Rundschau. It offers clues as to what Mennonite settlers learned from their Indigenous neighbours. It would seem absolutely nothing, for the exchange is an eerily silent one. It’s the quiet in the land meeting the silent of the woods. Archaeological evidence attests to an Indigenous agriculture in pre-contact Manitoba, but the Mennonites rarely saw the Indigenous as agriculturalists. The silence between the Mennonites and Indigenous as revealed in the Rundschau is startling. Indeed, only two letters among about two hundred from 1880 to 1885 even mention the Indigenous, and both describe them as a silent people. Settlers and Indigenous don’t talk to each other, even though they meet. There’s a social element, but the environmental one takes prominence.

In a September 1883 letter, a writer, signing “A Reader” (Ein Leser), from Niverville, places the Indigenous as an indelible part of the natural world. They don’t belong to wider society. The letter outlines the fall hay and wheat harvest, wheat hitting eighty-one cents a bushel, labour shortages, a new round of self-binder purchases, a question about spiritual health. And then A Reader announces, out of context, that “theft as we experienced it in Russia we don’t know here.” In fact, the only thief is the occasional “fox, which takes a chicken here and there. A bear was seen at Lichtenau at a short distance,” harmless enough, although “birds that resemble crows do damage in the grainfields.” The writer then leaves the idea of “theft” and does an aside on animal sightings: deer, skunks, rabbits, squirrels, and prairie chickens. But then A Reader takes another turn and links the two themes, culture and nature. Having made the point that there is less theft in Canada than in imperial Russia, A Reader also asserts there is less begging in Canada than in imperial Russia, but without leaving the subtheme of nature. As A Reader puts it, “Beggars are a great rarity here, and if there are ones now and then, they are redskins. These are, however, silent guests and don’t easily ask [verbally] for a gift, but wait till something is handed to them. Sometimes these Indians are also our neighbours, yet they often move from place to place.”46

It’s a description that echoes, almost word for word, an account by the village of Hochstadt’s Johan R. Dueck in the April 29, 1885, issue. In fact, it’s possible that “A Reader” is Dueck, as Niverville used to serve as post office for much more than that district. Nevertheless, in his letters, Dueck compares the Indigenous fighters in the Northwest that year to Manitoba’s more reticent Indigenous: “Here . . . only a few . . . let themselves be seen, when they, quite individually, pursue their work, the hunt . . . during which time they [do] come to the villages and beg, but [in a] very well-behaved [manner], in which they wait completely quietly, seeing what one will give them, and if [nothing is offered] they leave completely peacefully, in contrast . . . to the Russian beggar.”47 The Indigenous hunter is an “othered” being, nameless, kind and gentle in their dispossession, a Rousseau-esque noble savage, but irrelevant to anything the Mennonites require now that they had settled on their land. It’s a moment in environmental history.

Van Den Houte, Ghent, and Isaak J. Loewen, Blumenort

An eleventh and final settler story will appear in a family history book I am completing with my cousin Arden Dueck of Mexico, The House of Isaac and Maria. In part one we reference a story of Soetgen van den Houte, sentenced to die for her faith on November 27, 1560, in Ghent. A four-thousand-word farewell letter from prison to her small children – David, Betgen, and Tanneken – reads like a tract inviting a mindset required to enter the Kingdom of God, but also, by happenstance, environmental stewardship. She counsels her children to always practice “humility and meekness,” be “diligent to labor,” “love the poor,” “learn to be meek and lowly in heart,” “esteem yourself as the least,” “earn your bread by the labor of your hands,” “eat your bread with peace,” be not “anxious for great gain,” “overtax no one, but be satisfied with what is reasonable,” “if ye have food and raiment, be therewith content,” remember Daniel and friends, content with just “pulse and water,” “always care for those with whom you have dealings,” set not your “heart upon anything that is perishable,” “covet no one’s property.”48

How does Soetgen van den Houte’s letter fit into “settler stories”? Well, it’s my story. Soetgen came to my attention because of an environmental moment in 1900 in Blumenort. It was a long year of disease, an expression of environmental history.49 Diphtheria was likely the cause of the death of four of the six children of my great-grandparents Isaac and Elisabeth (Penner) Loewen, all dying over a fourteen-month period, from September 1899 to November 1900: eight-month-old Margaretha, three-year-old Johan, five-month-old Margaretha II, and five-year-old Elisabeth. My grandfather and Great-uncle Abram survived. Two years later, Great-grandfather Isaac pens a letter to his sons, ages eleven and nine, to admonish them to read Soetgen van den Houte’s letters. He directs them to the exact pages, 206 to 209 in the German version, and counsels them to “think deeply about the letter and also put a lot of effort into what she says on page 207.” What Soetgen says, writes Isaac, is that “true humility and simplicity are . . . necessary and good.” Isaac emphasizes humility and simplicity, and then adds, “We find a particularly beautiful teaching on vainglory, which spoils all good things, in Pieter Pietersz’s book,” presumably his 1638 Spiegel der Gierigkeit (Mirror of greed). The diphtheria tragedy, killing small children, an environmental moment at its worst, generates a teaching of humility and simplicity that undergirds the environmental moment at its best, when stewardship and contentment with little govern society’s relationship with nature.

Conclusion

Eleven stories. Chief Ke-we-tay-ash forced to reimagine the meaning of land. David Plett stitching a narrative of sea, river, field, and forest. Elisabeth Loewen recalling the provenance of nurture. Elisabeth Reimer embracing the new homeland’s climatic extremes. Gerhard Wiebe seeing a divine message in a lowly creature. Peter Wiens in sync with his environment. Maria Klassen grounded in hers. Prince Kropotkin hopeful for goodness on the “fat, black earth.” Peter Wiens listening to the seasonal rhythms of a new land. “A Reader” wondering about the Indigenous hunters who pass by as “silent guests.” Soetgen van den Houte laying out a principle of environmental interaction to settlers in distress. Eleven settler stories that carry meaning, for when the Mennonites arrived in Manitoba in the 1870s they entered a land that teemed with life. Their engagement with it is also our story. It’s my story. What is yours?

Royden Loewen is a senior scholar at the University of Winnipeg and held the Chair in Mennonite Studies for twenty-four years. He is the author of numerous books on Mennonite history.

- A version of this essay was delivered as an address to the annual meeting of the Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society on April 20, 2024. ↩︎

- “Master Number 11 Meaning,” Numerology.com, https://www.numerology.com/articles/about-numerology/master-number-11/. ↩︎

- Alexander Morris, The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba and the North-West Territories (Toronto: Belfords, Clarke, 1880), 313. ↩︎

- Donald Worster, “History as Natural History: An Essay on Theory and Method,” Pacific Historical Review 53, no. 1 (Feb. 1984): 5. ↩︎

- Ronald C. Macguire, An Historical Reference Guide to the Stone Fort Treaty (Treaty One) (Ottawa: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, 1980), 7. ↩︎

- Morris, Treaties of Canada, 314–15. ↩︎

- Dave Scott and Jonathan Dyck, “The Secret Treaty,” Canadian Mennonite, Feb. 23, 2024, 18. ↩︎

- Royden Loewen, Blumenort: A Mennonite Community in Transition (Steinbach, MB: Blumenort Mennonite Historical Society, 1983), 32–33. ↩︎

- Loewen, Blumenort, 49. ↩︎

- Royden Loewen, Family, Church, and Market: A Mennonite Community in the Old and the New Worlds, 1850–1930 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 98. ↩︎

- Loewen, Family, Church, and Market, 98. Letters deposited at the Mennonite Heritage Archives, Winnipeg. ↩︎

- Loewen, Family, Church, and Market, 103. ↩︎

- Loewen, Family, Church, and Market, 105. ↩︎

- To read an excerpt of Abraham F. Reimer’s diary, see Steve Fast, “Building and Leaving Borosenko: The Diary of Abraham F. Reimer,” Preservings, no. 48 (Spring 2024): 19–30. ↩︎

- [John C. Reimer, ed.], Familienregister der Nachkommen von Klaas und Helena Reimer mit Biographien der ersten drei Generationen (Winnipeg: Regehr’s Printing, 1958), 19. ↩︎

- [Reimer], Familienregister, 287–88. ↩︎

- Klaas J. B. Reimer, ed., Das 60 jährige Jubiläum der mennonitische Einwanderung in Manitoba (Steinbach, MB: Warte-Verlag, 1935), 26, quoted in Loewen, Family, Church, and Market, 100. ↩︎

- Gerhard Wiebe, Causes and History of the Emigration of the Mennonites from Russia to America, trans. Helen Janzen (Winnipeg: Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 1981); originally published as Gerhard Wiebe, Ursachen und Geschichte der Auswanderung der Mennoniten aus Russland nach Amerika (Winnipeg: Druckerei des Nordwesten, 1900). I referenced this story in “‘Come Watch This Spider’: Animals, Mennonites, and Indices of Modernity,” Canadian Historical Review 96, no. 1 (Mar. 2015): 61–90. ↩︎

- Wiebe, Causes and History, 1, 5. ↩︎

- Wiebe, Causes and History, 26, 28, 39, 40, 10–11, 45, 55, 56. ↩︎

- Wiebe, Causes and History, 21. ↩︎

- Wiebe, Causes and History, 22. ↩︎

- On mosquitoes see Lawrence Klippenstein and Julius G. Toews, Mennonite Memories: Settling in Western Canada (Winnipeg: Centennial Publications, 1977), 14; and Leonhard Sudermann, From Russia to America: In Search of Freedom, trans. Elmer F. Suderman (Steinbach, MB: Derksen Printers, 1974), 17. See also Frank H. Epp, Mennonites in Canada, 1786–1920: The History of a Separate People (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1974), 188, 191; and E. K. Francis, In Search of Utopia: The Mennonites in Manitoba (Glencoe, IL: The Free Press, 1955), 41, 42, arguing a role of the mosquito in sending most of the land scouts south. On grasshoppers see Rhinehart Friesen, A Mennonite Odyssey (Winnipeg: Hyperion Press, 1988), 48–53; and Epp, Mennonites in Canada, 1786–1920, 216. ↩︎

- Peter A. Elias, Voice in the Wilderness: Memoirs of Peter A. Elias (1843–1925), trans. and ed. Adolf Ens and Henry Unger (Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 2013), 59. ↩︎

- Elias, Voice in the Wilderness, 36–37. ↩︎

- Elias, Voice in the Wilderness, 39. ↩︎

- Elias, Voice in the Wilderness, 143. ↩︎

- Elias, Voice in the Wilderness, 149–50. ↩︎

- Royden Loewen, ed., From the Inside Out: The Rural Worlds of Mennonite Diarists, 1863 to 1929 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1999), 71–72. ↩︎

- Loewen, From the Inside Out, 70. ↩︎

- Loewen, From the Inside Out, 70–71. ↩︎

- Loewen, From the Inside Out, 71. ↩︎

- Loewen, From the Inside Out, 72–73. ↩︎

- Jacob E. Peters, Adolf Ens, and Eleanor Chornoboy, eds., The Outsiders’ Gaze: Life and Labour on the Mennonite West Reserve, 1874–1922 (Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 2015), 25, 40, 72, 62. ↩︎

- Peters, Ens, and Chornoboy, Outsiders’ Gaze, 111. ↩︎

- Peters, Ens, and Chornoboy, Outsiders’ Gaze, 111. ↩︎

- Peters, Ens, and Chornoboy, Outsiders’ Gaze, 112. ↩︎

- Peters, Ens, and Chornoboy, Outsiders’ Gaze, 113. ↩︎

- Peters, Ens, and Chornoboy, Outsiders’ Gaze, 113–14. ↩︎

- Peters, Ens, and Chornoboy, Outsiders’ Gaze, 114. ↩︎

- Peters, Ens, and Chornoboy, Outsiders’ Gaze, 115. ↩︎

- Peters, Ens, and Chornoboy, Outsiders’ Gaze, 116. ↩︎

- Peter Wiens, “Etwas für den Landwirth,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, Apr. 15, 1882, 2. ↩︎

- “Zur Beherzigung für die Landwirthe,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, July 18, 1883, 2. ↩︎

- Ein praktischer Landwirth in Russland, “Schwarzbrache oder Grünbrache?,” Die Mennonitische Rundschau, Apr. 29, 1885, 2. ↩︎

- Ein Leser, letter, Die Mennonitische Rundschau, Sept. 12, 1883, 1. ↩︎

- J. R. D., letter, Die Mennonitische Rundschau, Apr. 29, 1885, 1. ↩︎

- Thieleman J. van Braght, The Bloody Theater or Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians, trans. Joseph F. Sohm (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1938), 647, 649. ↩︎

- Linda Nash, “Beyond Virgin Soils: Disease as Environmental History,” in The Oxford Handbook of Environmental History, ed. Andrew C. Isenberg (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 76–107. ↩︎