The Controversy over Singing by Numbers

Peter Letkemann

A special characteristic of the Mennonites in imperial Russia was the practice of singing by numbers or cipher singing. As a musician and musicologist, I am often asked by Mennonite conductors and singers about the origin of this system. In this essay I would like to try to explain these questions briefly.

Origin of the Numerical System

The first evidence of using numbers for musical notation was found in an Arab manuscript from the thirteenth century. From the middle of the sixteenth century to the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were several isolated attempts to notate chants using numbers in Spain, France, Italy, and Germany.1 However, these various systems found no lasting resonance anywhere in the musical world.

The Swiss philosopher, writer, and composer Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) was the real progenitor of the numerical systems that would be used in Germany and France in the nineteenth century, and by the Mennonites in imperial Russia. From 1735 onwards, he was preoccupied with the idea of representing sounds with the help of numbers. This attempt to simplify the learning of music grew out of his own brief experience as a music teacher and his own difficulties in learning to read music. His aim was not to perform great oratorios or operas with the help of numbers, but to teach schoolchildren to sing simple melodies. On August 22, 1742, he presented his method to the Academy of Sciences in Paris, which reacted favourably, but not enthusiastically, to his new way of notating music. Professional musicians and composers, however, firmly rejected the system.

But Rousseau did not give in. The next year, he published a work to further explain and defend his numerical system. He would introduce a second method to be used for large and elaborately constructed movements. It was based on a middle octave, the corresponding numbers of which were placed on a line. Tones of the higher octave were placed above the line, those of the lower octave below. However, all his attempts failed; the numerical system, which he had called for with great enthusiasm, did not become widespread in France and Germany until thirty to forty years after his death.

Rousseau’s first method was taken up in France in 1817. In Germany, Rousseau’s second method was used and was further developed, particularly by Bernhard Christoph Ludwig Natorp (1774–1846). In 1809, Natorp was called to Potsdam by the Prussian minister of education, Wilhelm von Humboldt, and given the task “to bring the schools [in the province of Brandenburg] to such a degree of excellence and perfection that they could serve as examples for the other provinces to imitate.”2 Humboldt was deeply impressed by Natorp’s writings, whose goal was “to awaken the humanness in the person, or the person toward humanity.”3 Singing played an important role in the fulfillment of this goal. In 1813 and 1816 he published two books on teaching singing, which formed the basis of instruction in Prussian teacher training colleges for many years.4

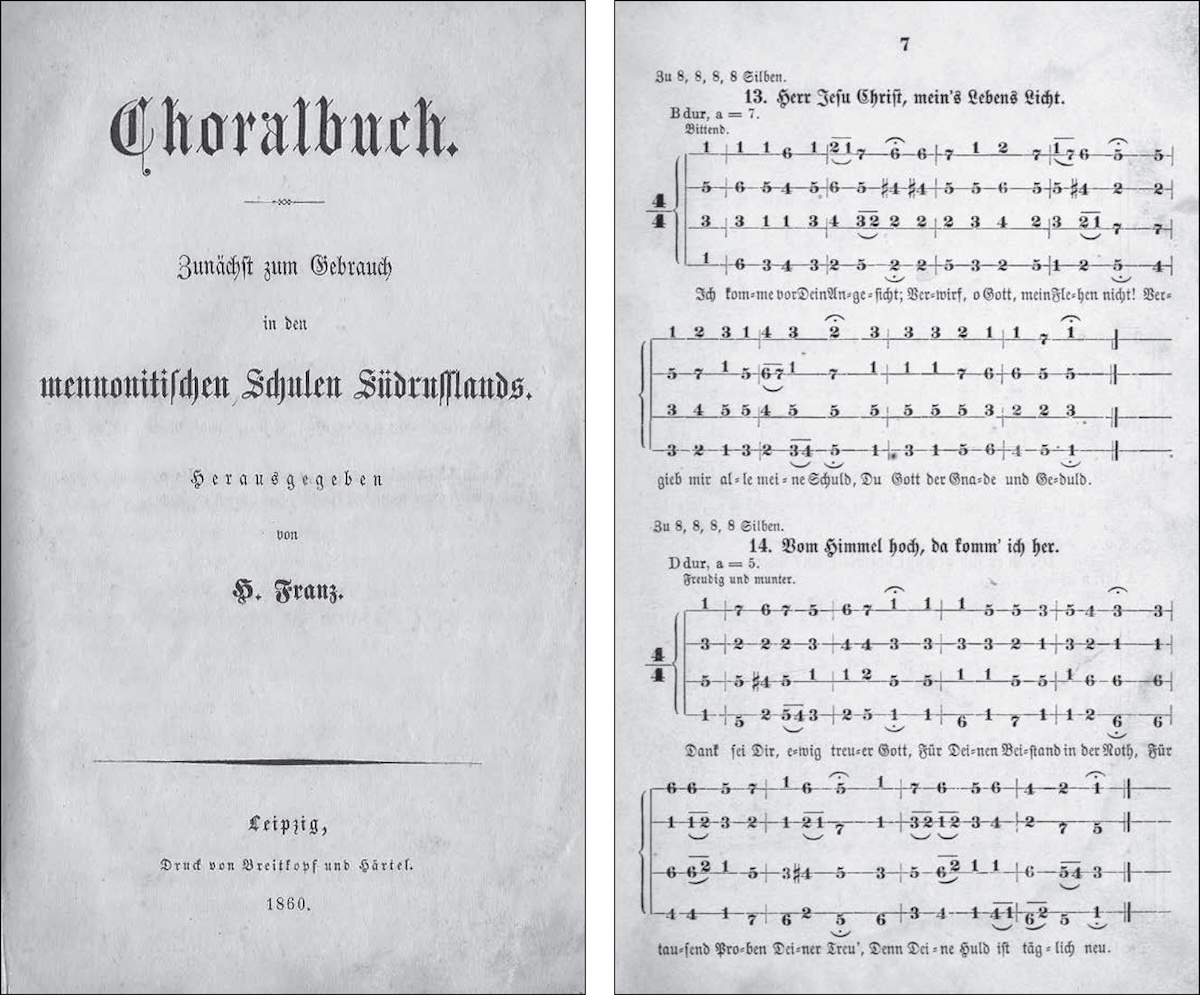

It was a mystery to me whether the Mennonite system of numerical notation was an original invention or whether it was borrowed from someone. For years I compared the first published Mennonite hymnal with numbers, Heinrich Franz’s Choralbuch (1860), with other German chorale books from the first half of the nineteenth century, until I finally found the presumptive source of the Mennonite system in the Berlin State Library, a collection of songs for church and school published by Jacob Behrendt in 1827.5 Behrendt was a teacher at the Royal Schoolteachers’ Seminary in Graudenz. The teachers who introduced the numerical system into Mennonite schools in the Russian empire, namely Tobias Voth, Friedrich Wilhelm Lange, and Heinrich Franz, had close ties to Graudenz. Whether the Mennonite numerical system is derived directly from Behrendt or from an older source is not certain. But I have not yet found an older source that is as similar to the Mennonite numbering system.

Introduction to Mennonite Schools

As far as I know, Tobias Voth (1791–ca. 1850) introduced the numerical system into Mennonite schools in imperial Russia. Voth had passed his teacher’s examination in Prussia and served for a time as a teacher in his home village of Brenkenhofswalde (1807–12) and later as a cantor and teacher in Soldin, Brandenburg (1812–14), and in Koenigsberg, Neumark (1814–20). In Prussia, at the time, it was common for the schoolteacher to also hold the office of cantor in the local Protestant parish.

In the years when Tobias Voth taught in the elementary schools of Brandenburg and Neumark, Natorp was responsible for the school system in these provinces. During this time he published several books on teaching music. It can be assumed that Tobias Voth as well as Friedrich Wilhelm Lange and Heinrich Franz, who had all lived and taught in the province of Brandenburg, were familiar with these books.

Voth remained in Koenigsberg until 1820, then temporarily took up a teaching position at the Mennonite village school in Komrau and then at the middle school in Graudenz. I assume that it was here (if not earlier) that he became acquainted with the variant of the numerical system of Behrendt. In 1822, Voth was invited to take up the teaching position at the school in Ohrloff, Molotschna. Here he served for seven years and taught, according to his own account, the subjects of religion, biblical history, reading, writing, arithmetic, German grammar, and “singing, either according to numbers or notes, with emphasis on church melodies.”6

This reference to the use of “numbers” for singing is the first of its kind among the Mennonites in the Russian empire. Singing was important for this musically gifted man. Yet he struggled with his health. As he wrote about his work in Ohrloff: “Through my work, through much speaking and singing, my health has suffered, my chest has become weak, and I often have to suffer pain.”7 In 1829, Voth left the Ohrloff school for various reasons. He taught for a time in Schoenwiese before leaving the Mennonite colonies for good around 1832, eking out a miserable existence in Berdiansk until his death around 1850. But as P. M. Friesen writes, the seed Voth sowed “did not die.” His former pupils in Ohrloff “received their first indelible Christian impressions and their love of education and culture from him” and enjoyed singing Voth’s songs until they were very old.8

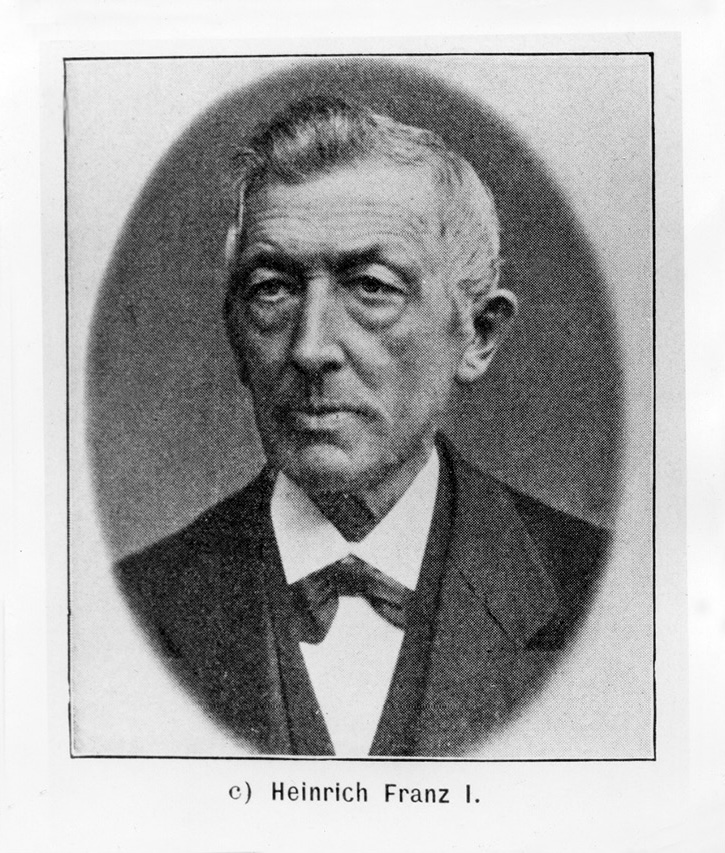

Yet, it was Voth’s junior colleague Heinrich Franz (1812–1889) who was recognized for introducing the numerical system into Mennonite schools. Franz received his teacher training from Friedrich Wilhelm Lange at the private Mennonite school in Rodlofferhuben. Lange also came from Brenkenhofswalde and had previously been a teacher in Graudenz. I assume that he learned the same numerical system here as Behrendt, or had learned it from Behrendt himself, and passed it on to his pupil Heinrich Franz. Franz passed the Prussian teacher’s examination in 1832 at the age of nineteen, taught in Brenkenhofswalde for several years, and then moved with the community to imperial Russia in 1834–35, where they founded the village of Gnadenfeld in the Molotschna colony.9 It was here in the village school that Heinrich Franz introduced singing by numbers.

Educational reform in the Molotschna colony helped to solidify singing by numbers in Mennonite schools. In the early 1840s, imperial Russian authorities placed schools in the colony under the control of the Agricultural Society. The chair of the society, Mennonite innovator Johann Cornies, set to work reforming schooling. As early as the fall of 1845, all teachers in the six school districts of the Molotschna settlement were given instructions to provide feedback on the proposed subjects on Cornies’s curriculum, which included singing by numbers, and to present a report the Agricultural Society within several months.10 These reports from the various school districts give an insight into what the teachers understood about singing lessons at the beginning of teaching the “new way.”

The teachers of the first district (which comprised the nine villages of Blumenort, Ohrloff, Tiege, Rosenort, Tiegerweide, Rueckenau, Margenau, Lichtfelde, and Neukirch) wrote: “This educational subject, which is so important from a religious point of view, must not take a back seat in any methodical school, because it makes it much easier to learn melodies by using numbers instead of notes. The beginning of this is the correct singing of the four main notes. . . . Once this has been properly practiced, one begins with easy melodies and observes a methodical progression from the easier to the more difficult. . . . The lessons themselves are given in the following way: the numbers and melody to be learned are written on the blackboard and sung together with the help of the teacher until this is done without mistakes, then by two or three and finally by individual pupils, and the same procedure is followed with the text as the song. It is useful for third and fourth grade students to memorize one verse of each song whose melody is being practiced.

“Once the melody has been well practiced in this way, the numbers of the melody are entered by the pupils in the singing exercise books provided for this purpose and the pupils are thus put in a position where they can relearn the melody themselves if they forget one or the other melody after the school years. In addition to singing at the beginning and end of school, two hours a week are devoted to singing lessons according to the curriculum.”11

The teachers of the fifth district (the villages of Prangenau, Elisabethal, Alexandertal, Schardau, Pordenau, and Mariental) wrote: “If pupils who cannot yet sing a melody were to learn to sing by ear, it would take them as many hours to learn a melody as it takes to sing fifty times six verses, as experience in our district teaches us. Singing by numbers is much more advantageous. In order to teach the children to sing this way, the numbers from the lower 1 to the higher 1 are written on the blackboard, just as the notes follow one another. These are practiced well with the pupils. If they can sing them correctly upwards and downwards, they must learn to drop a number from the middle and still hit the following one with the correct tone. Then the numbers are written to an easy melody, which is sung with the children until they can sing it well, and then the text is also sung.”12

The report of the sixth district shows that learning about thirty church melodies formed the content of the lessons. Two lessons a week were allocated to singing in each district: usually in the afternoon in the last (sixth) lesson, either on Monday and Wednesday, or on Tuesday and Thursday. As usual, the school day began and ended with singing and prayer. Of course, much depended on the talent and enthusiasm of the teacher.

Controversy Over Singing by Numbers

The introduction of singing by numbers in schools was meant to transform congregational singing. Many teachers and other “progressive” thinkers regretted the traditional method of singing in churches known as the “slow way” (langsame Weise), or old way (ole Wies), as it is called in Low German. In the preface to his Choralbuch, Heinrich Franz wrote: “There is no need to prove that sacred singing loses its beauty, purity, and correctness if it is merely propagated by ear – as it has been for a long time. In order to contribute to the best of my ability, in my small part, to restoring singing to its original purity and uniformity, first in my school and through it, finally, in the worship services of the congregation where I was employed as a teacher, as early as 1837 I arranged all the songs in our church hymnal according to their verse metre and, in the company of a dear friend and connoisseur of sacred singing [his former teacher, Friedrich Wilhelm Lange], collected the necessary melodies, which at that time were all only set to one voice.”13

In his efforts to restore the “beauty, purity, and correctness” of chorale melodies and congregational singing, Heinrich Franz reflected the ideas and ideals of Natorp and other German pedagogues and church teachers of his time.

In 1817 Natorp wrote, “Singing, as it is commonly heard in most of our churches, can hardly be called singing.”14 As he explained: “Many melodies are not sung by the congregations with the proper fluency. One gropes uncertainly after the melody and one sings the notes after the other. People very often eat up the melodies. One does not stay firmly in the voice of the melody and one embellishes the notes. One neglects musical punctuation and metre when singing.”15 Natorp’s words could have applied just as well to the congregational singing of the Mennonites. As Jakob A. Klassen, a popular teacher at the girls’ school in Chortitza, recounted from his youth: “Endlessly long hymns from the Gesangbuch were led by the Vorsaenger of the worshipping congregation. These hymns were sung with so many flourishes and embellishments that the melody became distorted to the point of being unrecognizable. In spite of my good ear, it was impossible for me to retain any of these strange melodies in my memory.”16

The publication of Franz’s Choralbuch in 1860 aided in the standardization of singing within Mennonite communities. For years, teachers and pupils copied the chorale melodies notated by Franz in numerals. However, Franz and other leading figures recognized that “the frequent copying of this chorale book by pupils would gradually distort the melodies again . . . so it [was] recognized as necessary to reproduce the chorale book in print and then to introduce it into the schools for singing lessons.”17 In 1852, Franz was commissioned by Baron von Rosen, chairman of the Guardianship Committee for Foreign Settlers, to print his chorale book.18

Franz’s Choralbuch was first published in a four-part version. A “one-part melody edition” for school use was published in 1865. A second edition of the four-part chorale book was published in 1880. Franz rightly recognized that “the more proficiently singing lessons are taught in schools, the sooner the desire for harmonious, polyphonic choral singing will become active. . . . In order to meet this desire, all the melodies in this chorale book appear in four parts.”19

The Choralbuch therefore not only promoted unison congregational singing but also multi-voice choral singing. Franz’s pupil Heinrich A. Ediger wrote: “Four-part singing, especially of the chorales, was diligently fostered by him. It is largely thanks to Lehrer Franz that the monotonous and plodding manner of congregational singing received fresh life, which contributed considerably to the edificatory effect of worship.”20

Some ministers, congregation members, and even some schoolteachers resisted singing by numbers. According to the surviving sources, the resistance was more intense and lasted longer in the villages of Chortitza, as well as in its offspring settlement Bergthal and in the six villages of the Jewish agricultural settlement in Kherson (known as the Judenplan) where Mennonites were settled to provide training in agriculture.

A lively description of the fierce dispute over singing by numbers can be found in the diary of Jacob David Epp (1820–1890), who served for years as a teacher and preacher on the Judenplan. In his diary entry from January 8, 1860, Epp wrote that he had received a letter from his fellow minister Isaac Klassen, who complained that “the divine service on the Day of Epiphany in Novozhitomir had been disturbed by the singing of a cipher [number] song.” On January 9, Epp recorded that the song leader (Vorsaenger) of the same congregation, Heinrich Olfert, “criticized Ohm Isaac Klassen for comparing this kind of singing to a drinking song and for speaking such nonsense about it. Olfert went on to say that Klassen had been the cause of the disturbance by rising in the middle of the singing and giving the congregation his blessing. . . . The rest of the congregation had finished singing three stanzas of the song, as announced.” In a meeting on January 10, Ohm (minister) Peter Loewen and his wife said that the disturbance was caused more by the behaviour of Ohm Isaac than the singing.21

Eight days later, Klassen was still “quite angry about the cipher singing, comparing it to the anti-Christian goings-on of the end times. His brother, Franz Klassen, had told him that such songs were military songs.” Franz had “responded with a loud lament: Dear, merciful God, a melody to thy glory sung to numbers in a divine service causes an outcry.” Two weeks later, Jacob Epp visited Elder Gerhard Dyck in Chortitza and told the elder “of the incident regarding the cipher music and the conduct of Reverend Is[aac] Kl[assen] in this regard. He . . . strongly disapproved of my colleague’s behaviour.” After his return, Jacob Epp visited Isaac Klassen. Epp wrote that Klassen and his wife “again raised the subject of the cipher music, and I told them what the Elder had said in this regard, namely that such music was not a cause for worry because it came from olden times, as could be seen from the notations of the very old song-books. In this way I tried to bring the matter to a close.”

As head minister of the Judenplan, Epp was also responsible for supervising the schools. He noted that during an inspection at the school in Izluchistaia on February 8, people were still singing in the old manner (described by Epp as “by ear”), and in Kamianka, teacher Johann Klassen said he did not want to sing by numbers.

Jacob Epp’s younger brother Abraham Epp, a graduate of the Chortitza Secondary School (Zentralschule), served as a teacher in Novopodolsk. Describing a school inspection on February 9, 1860, Epp wrote that he “started off with singing. . . . Songs were sung from our hymn-book, and at the close a few chorales in parts. The singing was very good. If only such schools existed everywhere.” On February 10, 1865, Epp visited the school in Novokovno, where Cornelius Penner served as a teacher. “Everything was still very much in its infancy here. Reading was good, but the teacher still had to learn writing and especially arithmetic himself. Number singing was still very poor.”

On Palm Sunday, March 20, 1866, a number melody was sung for the first time in the Novovitebsk congregation. Many schoolchildren were present at the service: “Perhaps the presence of the children prompted the precentor, teacher [Heinrich] Olfert, to announce a cipher melody at the close of the service (number 62, starting with stanza 5). The children sang with ringing voices. This is the first cipher melody sung in this church. . . . There has been cipher singing in the Chortitza church since last fall.” After his school visits in the spring of 1867, Epp wrote on February 15, “Cipher music is taught in all of the schools, except Izluchistaia, where singing is still by ear.” Singing by number was only introduced in this school in the spring of 1870.

On April 21, 1868, Epp wrote, “There was a disruptive performance today because of singing by numbers! The morning song was sung by ear (according to the ole Wies), and the final song was sung to numbers. Jacob de Veer from Izluchistaia hurried out again and drove home in a rage.” Three days later, de Veer visited Jacob Epp; de Veer said that he disliked the singing by numbers and could not attend such services.

During a visit to the school in Kamianka on February 11, 1870, the teacher “said that he did not wish to sing [with the children] because of the discord it caused.” Epp “encouraged him to sing, even cipher melodies.”

On Sunday, March 8, 1870, Jacob Epp attended the service at the school in Izluchistaia. He recorded: “Today’s singing was poor. The precentors are reluctant to lead the singing unless it is cipher music. Several verses of ear music were sung before and after the sermon. I hope we will soon be of one mind in regard to music. The majority have become indifferent about it, no longer viewing cipher music as such a great evil.”

A month later, on Palm Sunday, April 5, Epp wrote: “Our children . . . attended service in Izluchistaia, where a cipher melody was sung. They reported that Peter Peters and Mrs. Heinrich Siemens had walked out of the service.”

On December 31, 1870, Epp noted: “Cipher music, which was introduced earlier and caused a terrible uproar, has finally been accepted everywhere. The resulting animosities and conflicts have finally ended. Only two church members in Izluchistaia still refuse to attend services because of it, and that mainly out of stubbornness.”

Singing by Numbers in Chortitza

The dispute over singing by numbers in the Judenplan lasted at least ten years, but it was not an isolated or exceptional case. According to Epp’s diary, by fall 1865, the Chortitza church had started to sing by numbers. Therefore, it took almost twenty years from Cornies’s curriculum reform of 1846 before singing by numbers was finally introduced in the church, despite Heinrich Franz’s twelve years as a teacher at the Chortitza secondary school.

At the beginning of the 1860s, Heinrich Heese, an outspoken advocate of singing by numbers, wrote harshly about the “distorted singing” in the Chortitza colony. He claimed that “there still seems to be no taste [in the Chortitza area] for melodic singing.”22 In contrast, Jakob Toews wrote in the Odessaer Zeitung on February 11, 1863: “The credit for the fact that the chorales are being sung quite well, both in unison and in some cases even in parts, in the schools of the colonies must go to the efforts of Mr. Franz, who has been teaching here for thirty years. The introduction of the numerical method has brought about the situation in which crowds of curious persons, even from far-away colonies, annually stream to the public examinations in the Chortitza and Molotschna secondary schools . . . for the sole purpose of hearing the beautiful four-part singing, which is something ‘unheard of’ for them, in these schools.”23

Some sources recorded difficulties in other villages of the Chortitza colony. Jacob Epp, for example, described a case in the village of Burwalde on August 24, 1870: “Opposition to this singing by some members caused the precentors to withdraw their services, and now there was no end of bickering. Reverend Isaac de Veer was blamed for starting the row, but I did not question the Elder about the truth of this. Many think this kind of singing is an innovation and contrary to Christianity.”

Jacob Epp’s nephew, teacher David Heinrich Epp, also had to contend with contoversy over singing by numbers when he started teaching at the school in Osterwick. Under the pseudonym Lars Petersen, he described his own experiences of the boundary between the “old” and the “new” school in the years 1870–1880. When he took up his new teaching post, “the repertoire consisted of only three songs: ‘Liebster Jesu wir sind hier’ [always the second hymn, before the sermon, in Mennonite services], ‘Herr schaue auf uns nieder,’ and ‘Alle Menschen müssen sterben.’ . . . They were sung all the better because they were sung again and again; whether at the right time or at the wrong time, the little singers still lacked understanding for the time being. Of course, the same songs had to be used alternately at the beginning and end of school, according to the old way of singing, as we already know, with the many and varied flourishes and frills, whereby those in the know showed a very special virtuosity in improvising. But the new man [by which Epp meant himself] didn’t like that. He was a true radical who wanted everything to be different than it had been for so long. He already knew the numerical method, was in possession of Franz’s Choralbuch, and even owned a small edition of tasteful folk songs. Of course, he immediately tried to share some of this with the children, especially as [the teacher] proved to be particularly fond of singing and played his flute excellently. The children readily responded to the new melodies and songs. . . . It was too much fun to sing by numbers! . . . But for the good people, this seemed negative, almost anti-Christian. It seemed as if this innovation was going to knock the bottom out of the barrel of discontent. That was no way to sing in worship – and who had ever heard of singing by numbers? That is a mockery! And then there were songs like, ‘Der Mai ist gekommen, die Baeume schlagen aus’ [May has come, the trees are budding]. . . . The teacher realized that he could jeopardize the whole of his work by being reckless, so he dropped the singing lessons, albeit with a bleeding heart, and even forbade the children to sing by numbers.”24

From these various examples we can see that neither all preachers nor teachers, let alone ordinary members of the congregation, were convinced of the necessity of singing by numbers.

Conclusion

At the end of his well-known manual for teaching singing, Bernhard Natorp reiterated three of the main aims of singing lessons in elementary schools: to improve the singing of the congregation, to prepare the formation of choirs, and to enhance the entire life of the people through singing. Through the regulations of Johann Cornies, the efforts of Heinrich Franz and other teachers of the Mennonite secondary schools, and the dutiful service of a whole generation of village school teachers, these goals were achieved in the Mennonite villages of imperial Russia by the mid-1870s, because singing lessons in the schools not only led to an improvement in congregational singing, but also to the founding of many village choirs, singing societies, and even orchestras in the years after 1870.

Peter Letkemann is a historian and organist in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

- Johann Wolf, Handbuch der Notationskunde, vol. 2 (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1919), 387ff. ↩︎

- Letter from Humboldt to Natorp, May 23, 1809, quoted in Hans Knab, Bernhard Christoph Ludwig Natorp: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der deutschen Schulmusik in der ersten Hälfte des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts (Kassel: Bärenreiter-Verlag, 1933), 2–3. ↩︎

- B. C. L. Natorp, Grundriss zur Organisation allgemeiner Stadtschulen (Duisburg and Essen: Bädeker, 1804), 19. ↩︎

- B. C. L. Natorp, Anleitung zur Unterweisung im Singen (Essen and Duisburg: G. D. Bädeker, 1813); and B. C. L. Natorp, Lehrbüchlein der Singekunst für die Jugend in Volksschulen (Essen and Duisburg: G. D. Bädeker, 1816). ↩︎

- Jacob Jos. Behrendt, Sammlung ein- zwei- drei- und vierstimmiger Kirchen- und Schullieder. Motetten, Intonationen, Choräle, Liturgien, Chöre, Meß, Vesper und anderer geistlichen Lieder auf alle Festtage im Jahre, mit deutschen, polnischen und lateinischen Texte (Glogau: Heymannsche Buchhandlung, 1827). ↩︎

- P. M. Friesen, The Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia (1789-1910) (Fresno: Board of Christian Literature, General Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches), 693. ↩︎

- Friesen, Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia, 694. ↩︎

- Friesen, Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia, 96. ↩︎

- Friesen, Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia, 709–12. ↩︎

- Franz Isaac, Die Molotschnaer Mennoniten (Halbstadt: H. J. Braun, 1908) ↩︎

- State Archives of Odesa (DAOO), f. 89, op. 1, d. 1162. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Heinrich Franz, ed., Choralbuch: Zunächst zum Gebrauch in den mennonitischen Schulen Südrusslands (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1860), iii–iv. ↩︎

- B. C. L. Natorp, Über den Gesang in den Kirchen der Protestanten (Essen and Duisburg: G. D. Bädeker, 1817), 111. ↩︎

- Natorp, Über den Gesang, xi. ↩︎

- Jakob Abraham Klassen, “Autodidakt: Erinnerungen aus meinem Leben,” typescript, ca. 1915, Centre for Mennonite Brethren Studies, Winnipeg. ↩︎

- Franz, Choralbuch, iv. ↩︎

- Heinrich Dirks, “Aus der Gnadenfelder Gemeindechronik,” Mennonitisches Jahrbuch, no. 9 (1911–1912): 31 ↩︎

- Franz, Choralbuch, iv. ↩︎

- H. A. Ediger, “Meine Schulzeit bei Lehrer Heinrich Franz,” Der Bote, June 11, 1930, 1. ↩︎

- For most of the quotes from Jacob Epp, see Harvey L. Dyck, trans. and ed., A Mennonite in Russia: The Diaries of Jacob D. Epp, 1851–1880 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991). For entries not included in Dyck, see the original at Mennonite Heritage Archives, Winnipeg, vol. 1016. ↩︎

- Friesen, Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia, 113. ↩︎

- Odessaer Zeitung, Feb. 11, 1863, 121. ↩︎

- Lars Petersen, “In der Schulstube,” Der Bote, July 7, 1937, 2. ↩︎