The Crow Wing Trail

Leonard Doell

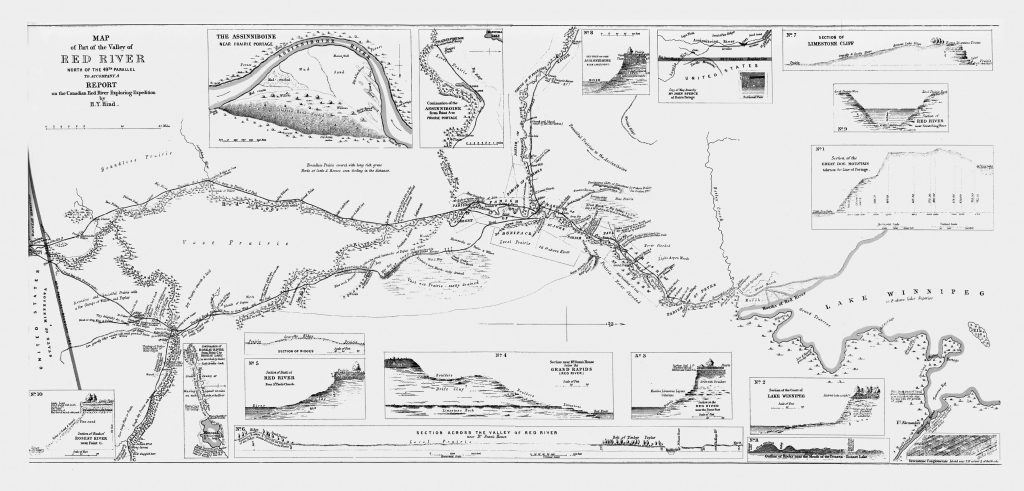

The Crow Wing Trail, also known as the St. Paul Trail,1 ran along the east side of the Red River from Upper Fort Garry (now Winnipeg) down to Pembina and from there to St. Paul, Minnesota. This trail, used for various purposes by Indigenous peoples, was the primary trade route for Métis traders travelling between the Red River Settlement and St. Paul from the 1840s to the 1870s. Thousands of Métis-driven Red River carts made the trip, transporting goods and people from spring to autumn.

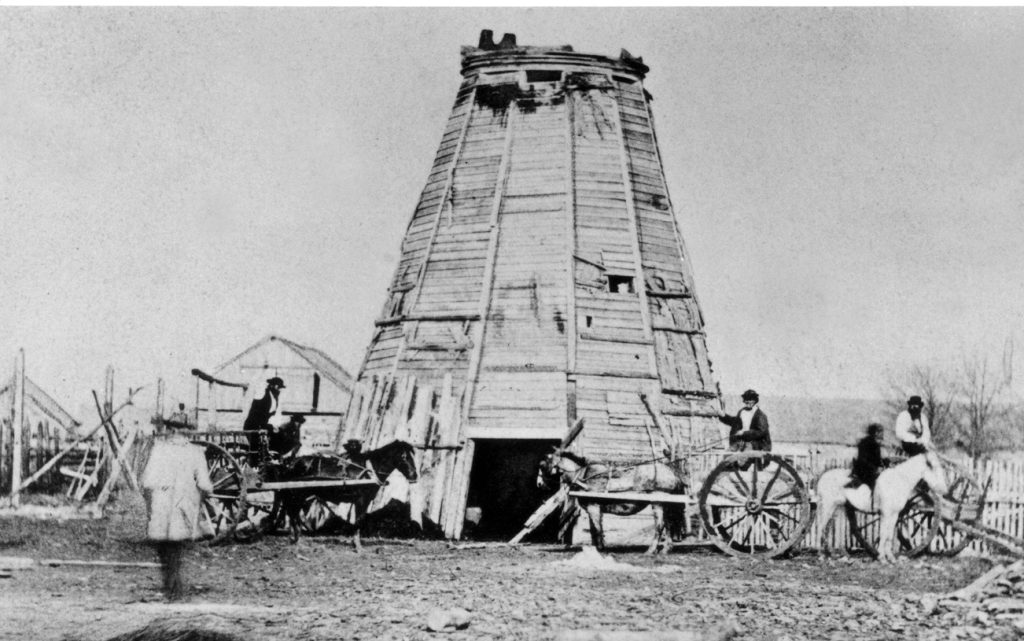

The journal of Alexander Henry, a fur trader with the North West Company, describes the introduction of Red River carts in 1801 at Fort Pembina. Initially, these carts were small, pulled by horses, and equipped with solid wood wheels measuring three feet in diameter. They could transport up to 450 pounds. Later, larger wheels allowed these carts to carry nearly double this load.2

One letter writer to the Red River Valley Echo elated his experience of these carts: “I well remember the Red River carts that passed our place in regular caravans, going north and south on the trail. These carts were high wheeled, all wood, tied together with fresh rawhide which, when dried, was almost like an iron band. No iron was used in the construction. A pony [or ox] was hitched between the shafts of each cart. Since the axles of these carts were never greased because grease softened the wood” – grease would also have collected dust, causing axles to wear down faster – “they all ran dry and each wheel played a different tune. They could be heard for miles. The cart wheel band.”3

The carts were very practical, easily made and easily fixed. In the trip from St. Paul to Fort Garry often as many as four or five axles would need to be replaced. In case of a breakdown a nearby bluff of trees would usually supply the materials needed in order to make repairs.

The trail was not a narrow set of two tracks but a wide trail made of many sets of tracks. As the need became greater to haul more by land, Métis drivers would manoeuvre multiple carts at the same time. The extensive tracks created by these carts lessened the likelihood of the cart getting stuck in the prairie mud.4

By the 1870s, the scene had changed. There was a rapid incoming of settlers and numerous American traders travelling to the Red River settlement. In 1859 the merchants of St. Paul had launched the first steamboat to go north to Fort Garry. Carting remained a major mode of transport through the 1860s, but it was gradually replaced by the steamboat, which could carry heavier cargo, undermining the role of the Métis in the transport of goods and people.5

In the summer of 1873, a delegation of ten Mennonites and two Hutterites came to inspect the land in Manitoba with the hope of finding a new home. The delegates arrived in Winnipeg on June 17. They were greeted by the premier and other government leaders, and newspaper reporters. The next morning, they left as a large party of twenty-four men, which included John Norquay, the provincial minister of agriculture, who later became the first Indigenous premier of the province.6

The lands they were going to inspect are now the eight townships on the east side of the Red River that became known as the East Reserve. The group left at 8:00 on the morning of June 18. The American Mennonite publisher John F. Funk reported on the inspection tour for his newspaper: “The sun shone warm and pleasantly; vegetation looked cheerful, and here and there we noticed the half-breed farmers ploughing. We anticipated a pleasant ride. We crossed over the Red River on a Ferry-boat and then struck off in a southeastern direction over the prairie and towards a place known as Oak Point, about forty miles distant, where the Government has a building for the accommodation of parties traveling over the Dawson Road.”7

It rained very heavily that afternoon and the horses and wagons became stuck in the mud. As John Funk wrote to his wife: “The ground was wet and swampy – several of the horses sank into the mire and could go no further. We must unhitch them, go down into the mud and water halfway to our knees and draw the wagon out by hand. This happened at least five or six times and once we had to draw the wagon at least a ¼ of a mile while the empty wagon cut the mire half way to the axles.”8

That evening they arrived at Government House, but no arrangements had been made and the housekeeper refused them entry. So they stayed at the Hudson Bay Company house. On June 19 the morning meditation was on Psalm 101. In retelling the story, Henry Gerbrandt reflected on the experience of the delegates: “Although the Psalm spoke of thankfulness, it seemed just a little odd to thank God in view of the waste country they had witnessed the day before. While their own fields in Russia were beautifully ripe unto harvest, the soil on which they travelled was hardly ready nor fit for seeding. They also noticed that there appeared to be little wildlife.”9

The water was not good and had to be strained and boiled. Mosquitoes were also a great problem. “Mosquitoes reign here in countless myriads,” reported Funk, “and are indeed a very unpleasant pest.”10 On the morning of June 20, they arrived in what would become the East Reserve. Here, near the future village of Chortitz, they discovered a water supply and fertile land along with a few squatting farmers. Even though they viewed only part of the reserve, “the group decided to terminate the journey and return to Winnipeg. They did not discover that some of the other townships were more swampy, stony and of much poorer soil. They had to learn bitterly through hard experiences several years later.”11

The group followed the Crow Wing Trail as they travelled back to Winnipeg. In Winnipeg they split up, with one group going to the United States and the other staying to inspect what would become the West Reserve.

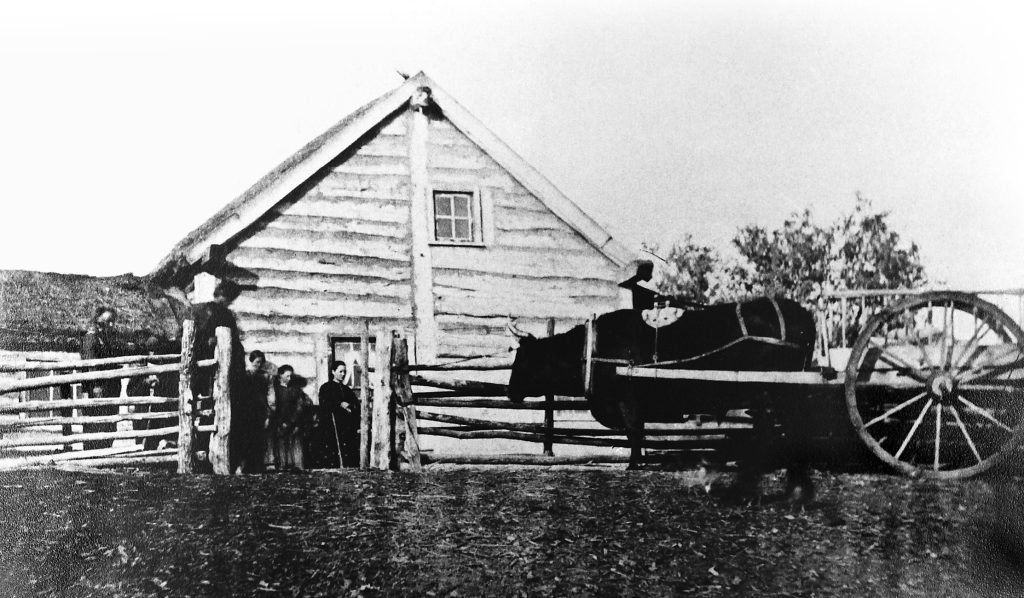

When the Bergthal and Kleine Gemeinde Mennonites immigrated to Manitoba in 1874, their steamboat stopped at the meeting of the Red and Rat Rivers. It was here that “the women and children were loaded on ox carts and taken to immigration sheds about five miles away.”12 Jacob Y. Shantz, a Mennonite businessman from Ontario, had been hired by the government to construct these immigration sheds for the Mennonites. In a letter to the surveyor general, J. S. Dennis, he wrote: “I have selected a plan to the best of my ability, most proper for to put up the building as it is not far from the boundary of the reserved township, but there is a little lake there and the nearest place to get wood also.”13

In a letter of July 24, 1874, he wrote again to Mr. Dennis, saying sheds had been “built on quarters of sections 17, 18, 19, and 20 in Township 7, Range 4 East: southeast quarter of section 17, southwest of section 18, northwest of section 19, and northeast of section 20.”14 These sheds were about twenty feet by one hundred feet in size. They did not have a floor or shingles; they were divided into several small sleeping quarters with a space for dining in the centre. 15 The Crow Wing Trail passed by these immigrant sheds.16

Not long after the Mennonites settled in the East Reserve, the government closed the trail. In part, this closure was due to pressure by the Mennonites. They expressed concern that some of their best farming land was divided by the trail, which followed a curve through the northwest corner of the reserve. In October 1888, Mennonites of the municipalities of Hespeler and Hanover sent a petition to the government seeking an alteration of a public highway that was to be built. They did not want the highway to follow the old trail but to be located “as found most practical by the municipality, between the full sections 6-5, 7-8, 18-17 leading north etc.” The Mennonites threatened that if the road was built as the old trail once went, they would “demand a recompensation from the municipality which would prove to be a serious expense for us.”17

Meanwhile, the next spring a letter was sent to the minister of public works, James S. Smart, by Member of Legislative Assembly Martin Jérôme, asking that responsibility for the Crow Wing Trail be transferred from the province to the municipalities, for in his municipality of De Salaberry the people were very “anxious to have it opened to public traffic,” saying that “it is the best highway from St. Boniface to the Boundary line.”18

The Crow Wing Trail is just one example of the many trails that were eventually closed due to the demands of farmers and changing transportation routes. This trail served several purposes at one time with many different groups using it. For the Mennonites of the East Reserve, the trail provided a means for inspecting and entering the land and also a means for purchasing goods and selling their products, but perhaps most significant is that it brought Mennonites into contact with various groups of people who had differing lifestyles and world views.

Leonard Doell is retired and lives near Aberdeen, Saskatchewan. He is an active member of the Mennonite Historical Society of Saskatchewan and enjoys doing genealogical research and learning about Mennonite and Indigenous history.

- Bill Schroeder refers to it as a Chippewa-Ojibway trail. William Schroeder, The Bergthal Colony (Winnipeg: CMBC Publications, 1970), 82. ↩︎

- Edith Paterson, Tales of Early Manitoba from the Winnipeg Free Press (Winnipeg: The Winnipeg Free Press, 1970), 21. ↩︎

- Thomas Mulvey, letter, “Former Days Recalled,” Red River Valley Echo, July 3, 4, 5, and 6, 1958. ↩︎

- D. Bruce Sealey and Antoine S. Lussier, The Métis: Canada’s Forgotten People (Winnipeg: Manitoba Métis Federation Press, 1975), 21. ↩︎

- Sealey and Lussier, Métis, 70–71. The scale of the cart trade in its heyday was remarkable: “In 1843, when Joseph Rolette had started a regular service between Fort Garry and St. Paul, he found that half a dozen carts were sufficient for his purposes. By 1858 the number had grown to 600. In 1865, on one trip alone, Norbert Welsh travelled with a train of 300 carts; and by 1869 some 2,500 Red River carts lunged and screeched their ungreased way behind the ponderous ox-teams that hauled them along the road to St. Paul.” George F. G. Stanley, Louis Riel (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1963), 37. ↩︎

- Henry J. Gerbrandt, Adventure in Faith (Altona: D. W. Friesen & Sons, 1970), 51–52. ↩︎

- John F. Funk, “Notes by the Way,” Herald of Truth, Sept. 1873, 154. ↩︎

- Melvin Gingerich, “John F. Funk’s Trip to Manitoba in 1873,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 34, no. 2 (Apr. 1960): 148. ↩︎

- Gerbrandt, Adventure in Faith, 52–53. ↩︎

- Funk, “Notes by the Way,” 155. ↩︎

- Gerbrandt, Adventure in Faith, 53. Of the squatters mentioned, one such person, Mr. Charles Sauvé, wrote to Wilfrid Laurier on Jan. 16, 1897, asking that he be compensated for the land he had given up with the coming of the Mennonites. He and thirteen others had built houses and made improvements on their lands. He wrote that many of these people had sent in applications and petitions to the government asking for these claims to be recognized but had never received a reply. Minister of the Interior Clifford Sifton received this letter and wrote to Laurier explaining the situation to him: “The claims which he [Sauvé] refers to are claims which would be absolutely impossible to take up. It would require Parliamentary vote to compensate these people and consequently therefore every man who had ever broken a foot of land on Government property, and failed to get entry for it, would claim compensation. I have been steadily refusing claims of this kind for the last three weeks. My own view is that they are a class of claims which are of no account whatever.” Sir Wilfrid Laurier fonds, MG 26-G, vol. 35, 11439–42, Library and Archives Canada (LAC), Ottawa. Archival materials cited in this article were collected by Adolf Ens. ↩︎

- Schroeder, Bergthal Colony, 51. ↩︎

- Jacob Y. Shantz to J. S. Dennis, June 9, 1874, RG 15, vol. 231, file 1047, LAC. ↩︎

- Jacob Y. Shantz to J. S. Dennis, July 24, 1874, RG 15, vol. 231, file 1047, LAC. ↩︎

- Schroeder, Bergthal Colony, 51. ↩︎

- Susan Hiebert, “Indians, Metis and Mennonites,” in Mennonite Memories: Settling in Western Canada, ed. Lawrence Klippenstein and Julius G. Toews (Winnipeg: Centennial Publications, 1977), 50. ↩︎

- “Petition of the Municipality of Hespeler & Hanover re alteration of a public highway,” Oct. 27, 1888, “Public Works – Minister, Correspondence re: Old Trails,” Minister of Transportation and Government Services office files, GS 0123, GR1607, G 7965, Archives of Manitoba, Winnipeg. ↩︎

- Martin Jérôme to James S. Smart, Apr. 13, 1889, “Public Works – Minister, Correspondence re: Old Trails.” ↩︎