Selling Bibles: The Bartsch Brothers in Central Asia

Alan M. Guenther

In the late nineteenth century, as Mennonite communities in Russia were undergoing rapid changes, Johannes Bartsch (1848–1915) began to work as a Bible colporteur, or salesman, for the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS).1 He was subsequently part of a group of Mennonites who migrated to Central Asia, following their teacher, Klaas Epp. These experiences brought Bartsch into close contact with Muslims, the first as an evangelist seeking to communicate the Word of God and the second as an immigrant dependent upon the welcome and goodwill of Muslim rulers and neighbours. The story of these interactions is contained primarily in the annual reports of the BFBS and in a series of articles Bartsch published in the Herald of Truth in the early part of the twentieth century. His brother Franz (1854–1931) published a book, Unser Auszug nach Mittelasien (Our move to Central Asia), that gave further details of these encounters from his own perspective.

As Johannes Bartsch tells the story, his association with the BFBS began with his own recognition of his need for salvation in the summer of 1875, during a visit with his family and the Mennonite congregations on the Volga and on the steppes of Russia. His mother and two brothers, including Franz, had settled in the village of Hahnsau in the Am Trakt settlement after leaving Prussia. For several years Bartsch had worked in Germany as a wine merchant. During a two-month furlough in Russia, he was challenged to consider the future of his soul. Having made his choice, he agreed to stay in Russia and began to contemplate how to earn a living. He had a desire to serve in some full-time ministry, and was offered an opportunity by a visiting representative of the BFBS, who was looking to appoint someone from an evangelical denomination that could speak the German language to be a colporteur. Although he felt some aversion to “carrying around a bundle of books,” Bartsch felt this was the calling of God.

The Bible Society had been active in Mennonite communities in Russia since 1819.2 In 1821, representatives of the society sought to impress upon the leaders of the Mennonite community of Molotschna their unique opportunity and consequent responsibility to evangelize their diverse non-Christian neighbours, including the Nogai who practised Islam.3 Mennonites showed little interest in this task. The Bible Society also requested the Basel Mission Society send a missionary who could learn the Nogai language in order to communicate the gospel to them.4 The young man who arrived, Daniel Schlatter, ended up working as a missionary among the Nogai.5 Almost sixty years later, Bartsch would establish a connection with the BFBS, sharing its desire to spread the word of God to Muslims in their own languages.

On January 1, 1879, Bartsch was appointed as a colporteur of the Bible Society and he began his ministry in Saratov and along the Volga River valley. He was also asked to travel northeast to Siberia where his headquarters would be at Perm. From there he visited a number of mining sites in the Ural Mountains. As he travelled for the BFBS, Bartsch encountered Muslims in Orenburg, on the Ural River. A new edition of the “Kirghese-Tatar” New Testament had been published by Kazan University’s press, and Bartsch had been sent to Orenburg with another worker to circulate it as widely as possible. In their monthly reports they noted, “Notwithstanding the nomad state of the Kirghese [Kazakhs], nearly 100 copies were sold before the Mullahs [religious teachers] noticed the new book, and forbade its purchase.”6

At the end of July 1881, Bartsch resigned from his position to join the group of Mennonites who had moved to Central Asia the year before. A number of Mennonite families from the Am Trakt settlement and from the Molotschna region had decided to migrate to Central Asia, partly over the issue of military conscription, and partly in response to the millennialist ideas of Klaas Epp. Johannes’s younger brother Franz and his mother left in 1880 on this trek. As these groups travelled farther east, they encountered a number of diverse Muslim groups. On the Kazakh steppe along the Ural River they met Kazakhs, from whom they purchased feed for their animals as well as milk for their people. Franz Bartsch and his wife had acquired some facility in the Tatar language, which they could put to good use in speaking with the Kazakhs. He noted in his account that Kazakh, Tatar, and Uzbek-Sart were all Turkish dialects that were mutually comprehensible.7 However, apart from the occasional opportunities for trade, the Mennonites had little to do with the inhabitants of the land through which they were passing. Franz Bartsch did note several times, however, that the young men among them were quicker to become fluent in the Kazakh language.

One such young man was Hermann Jantzen, who joined the caravan as a fourteen-year-old boy along with his family. In his autobiography he recalled that a young Sart who asked to accompany the caravan to Tashkent taught him the Uzbek-Turkish language daily as they travelled together.8 Because of his facility with the language, Jantzen would be invited to serve as an interpreter for Sayyid Muhammad Rahim Bahadur II, the Khan of Khiva, and would add the study of the Qur’an and other Muslim texts to his language study.9 Jantzen also described how he, as a young man living among the Mennonites that stayed in Khiva, was called as a missionary to the Muslims when an elder of the community, Jacob Toews, commented that with his language skills, Jantzen could become a missionary to the local population.10

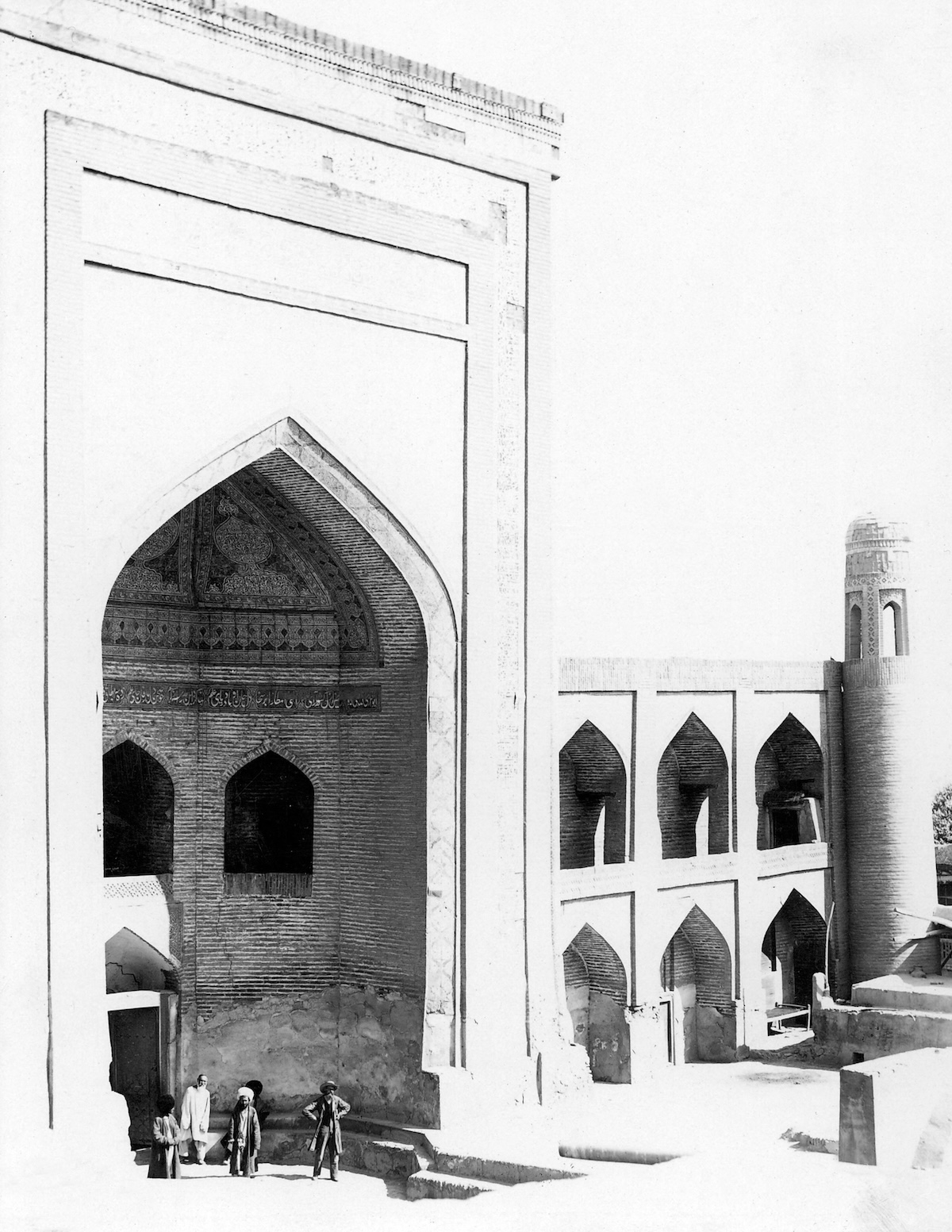

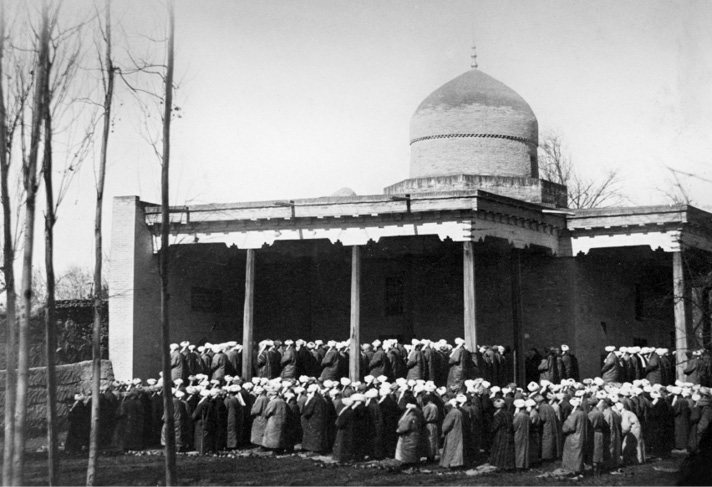

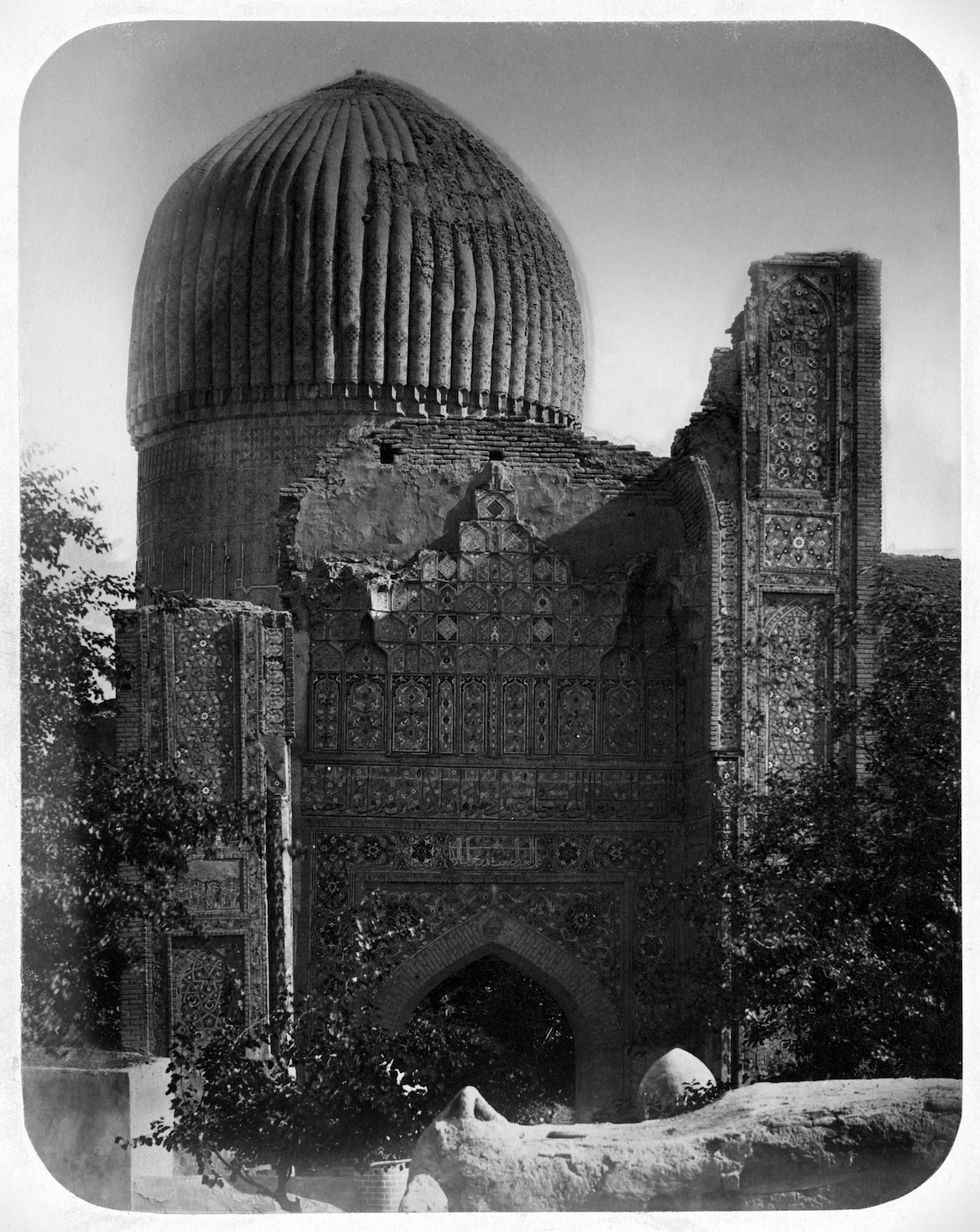

In his account Franz Bartsch described the major Muslim urban centres through which they passed, including Turkistan, Tashkent, and Samarkand. He commented on the unique Muslim architectural features encountered by Mennonites during their journey. In one lovely valley in the Tien Shan mountains between Tashkent and Samarkand they heard that according to local lore, Muhammad had hewn a pass through the mountains with a hoe. A nearby inscription seemed to confirm the legend, but the travellers were unable to decipher it.11 Samarkand was impressive, with its many old madrasahs (Muslim universities) and mosques with their beautiful mosaics, as well as the tomb of Tamerlane or Tīmūr Lang, the founder of the Timurid dynasty in the fourteenth century.

(MENNONITE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES (BETHEL COLLEGE), 2004-0078)

When the travellers crossed the Russian border into the region of Bukhara, they were forcibly compelled to return to Russian territory.12 Through the advice of a sympathetic official, they began negotiations with Muslim leaders in Samarkand to settle on a tract of land straddling the Russian-Bukharan border. Since this was land set aside as a religious endowment or waqf, it was administered separately from the state under the supervision of an appointed mutavali (caretaker).13 The mutavali and other Muslim leaders agreed to lease the land to the Mennonites, but once again the Bukharan officials objected to their presence. Several Mennonite leaders were called to appear before the local bek (chieftain) who wished to assign another portion of land to them. In his book, Franz Bartsch described how he hesitated when he was asked to explain their reason for undertaking the trek because he felt he lacked the necessary vocabulary in the Uzbek-Sart dialect to explain spiritual matters. He also provided his assessment of Islam in which he described the Prophet Muhammad’s teaching as a mixture of Judaism, Christianity, and fantasy.14 Because of these sources, he wrote, Muslim teaching included a belief that the Antichrist would come only to be destroyed by the Christ when he returned. Bartsch felt he could use this concept to introduce the Mennonites’ millenarianism which motivated their trek. But as soon as he mentioned dajjāl (the Antichrist), the bek objected violently and imprisoned the delegation for the night. The following day, they returned to the settlement with a contingent of the bek’s soldiers, who forced them to pack up their belongings and move back to the city of Serabulak in Russian territory. Here other Muslims proved more hospitable as they willingly opened their village to the destitute Mennonites and even permitted them to use their mosque for Sunday worship services and weddings.15

Meanwhile, back in the Mennonite colonies along the Volga River, Johannes had resigned from his position with the BFBS in Saratov at the end of July 1881 in order to travel with another group of emigrants heading for Central Asia. He joined the caravan as it passed through Orenburg, where he was doing colportage work. He took a small number of Bibles to give away to Muslims and Jews along the way. When they arrived in Turkistan shortly before Christmas in 1881, the decision was made to winter in that city, and Bartsch took the opportunity to distribute his Bibles. Through certain incidents that happened on the journey, Bartsch turned from being an ardent follower of Klaas Epp to an opponent. Disillusionment had likely already set in that winter in Turkistan since he sent an account of his journey to the Bible Society and requested a consignment of books be sent from St. Petersburg, indicating his future plans. When the caravan arrived in Tashkent, he separated from the group and remained in the city to establish a Bible depot, resuming his work as a colporteur with the BFBS. When the rest of the emigrants, including Klaas Epp, reached those in Serabulak who had departed a year earlier, Franz Bartsch also found himself out of favour with Epp, and decided to join his brother Johannes in Tashkent to assist in his Bible distribution ministry.16

Johannes Bartsch described in detail one of his first encounters with a Muslim as he began his work in Tashkent. The Muslim had hailed him and expressed a desire to see his books as he was on his way to the bazaar in the older part of the city. The Muslim characteristically declared “Bismallāh,” or “in the name of God,” as he took the book. When he inquired what kind of book it was, Bartsch replied that it was the gospel. After some reflection, the Muslim responded, “Injīl ‘Īsá!” meaning “the gospel of Christ.” He then further indicated that he was aware of the other holy books: the Taurat of Moses, the Zabūr of David, and the Qur’an of Muhammad. He told Bartsch, “The Koran is good, give me the Koran; this book was not written for us.”17 Bartsch replied that the gospel was for all people – for Christians, for Jews, and for Muslims. The Muslim began to leaf through the book and asked for the price. He was surprised at the low cost but tried to haggle with Bartsch and buy it at even a lower price. Bartsch, however, refused to budge, and the Muslim eventually bought the New Testament, took it in both hands, raised it to his lips and to his forehead, and murmured, “Bismallāh.” The crowd that had gathered to witness the transaction were fascinated by the exchange and at Bartsch’s insistence on the payment of the full price. His stock of that edition of the New Testament was soon sold out as a result.

In the bazaar Bartsch found the selling of his books to be difficult. He realized he would have to stock many more languages because besides the Sarts and Tatars there were Persians, Arabs, Uzbeks, Afghans, Tungus, Hindus, and Jews. He also concluded that colportage work among Muslims was very different than among Christians, because Muslims were “avowed enemies of Christianity.”18 Bartsch also stated that unlike his previous ministry along the Volga and in northern Russia, here he was prohibited from going into homes and had to conduct his business primarily in the bazaar and only with the men. The reason for this was the practice of purdah: the seclusion of women in orthodox Muslim families. Nevertheless, in his report to the BFBS Bartsch recounted a more favourable reception of his wares as time went on and as he became more known in the region: “As I make my appearance (I am beginning to be well known) some books are asked for, most probably Persian (which is the most currently used cultivated language in these parts). A book is bought, and the buyer begins to read aloud. The 5th chapter of Matthew made especially a deep impression. Some were sitting Eastern fashion, some standing, but from all or almost all an expression of wonder was heard. This was more marked still, as one day in my hearing the 22nd chapter of the Revelation was read, about Jerusalem the Golden. The deepest attention was given in order not to lose a word, and the necks of the hearers were stretched out towards the reader.”19 During one of his first trips into Bukhara, Bartsch encountered a mullah from one of the colleges who objected to the books he was selling and declared them to be lies. Bartsch silenced him by exclaiming, “How can the Book lie which comes from Jesus and Mas[i]h Allah?”20 He was appealing to the Muslim’s belief in Jesus as a prophet sent by God and as the Messiah from God.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-DIG-PPMSCA-14156)

In Tashkent, Johannes Bartsch set up another depot – a bookstore where Bibles, Testaments, and portions of scripture in all the languages and dialects were sold and shipped to other points. As directed by his superior from the BFBS, he appointed another young Mennonite, Jacob Neumann, to assist his wife at the depot when he was away from home, and appointed two more colporteurs for Siberia and one in Khiva. Mennonite names listed in the annual reports of the BFBS included Johannes’s brother Franz in Siberia, Jacob Hamm in Irkutsk and Siberia, and Jacob Stärkel in Khiva,21 who, when he immigrated to the United States in June 1885, was replaced by Henry Ott. Franz Bartsch established a depot for Siberia in Omsk. Two years later he was joined by his brother-in-law, Heinrich Wölke, in his Siberian travels. Jacob Wiebe (described as another brother-in-law) was also listed along with Wölke for the Omsk region. Towards the end of 1889, Jacob Suckau and his son John joined Johannes Bartsch in Tashkent. With the addition of Cornelius Wall in Tashkent, it was felt that Jacob Neumann could be sent to help Franz Bartsch in Siberia.22

From the BFBS base in Tashkent, Johannes Bartsch travelled through the surrounding areas, selling Bibles and scripture portions. Generally his wares received a more favourable reception from the Christian population than from the Muslims, but every report continued to indicate sales of the newly published Kazakh New Testament. In the opinion of the BFBS, however, opposition from Muslim was the greatest obstacle to their ministry in Central Asia, more significant than the difficulties of travel and climate: “The most serious drawback of all is the strong hostility of the Muhammadans. Their antipathy to the colporteur strengthens as the object of his visit is understood.”23 The multiplicity of languages was also a problem, and the agent for the region, Mr. Nicholson, reported that Bartsch was anxiously awaiting translations of portions of the Bible in other local languages.

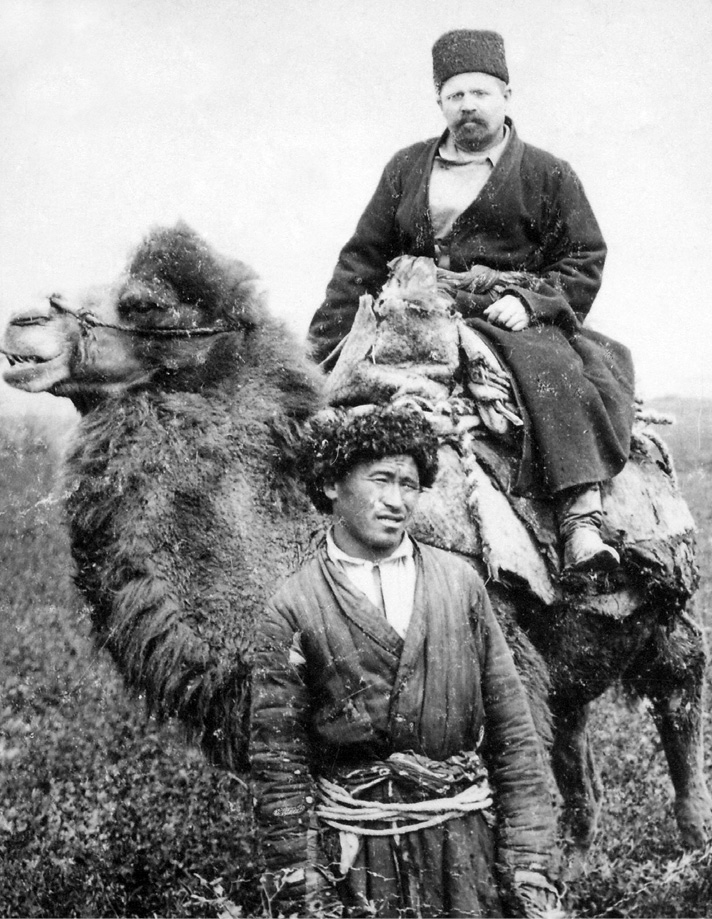

Bartsch gave an extended account of one of his journeys from Tashkent to Khiva in 1885. Because of rumours of war, he was forced to take a longer road, crossing the desert between Kazalinsk and Khiva. After one abortive attempt when he was deserted by his Kazakh guide, Bartsch joined a caravan also travelling that route. Bartsch described in detail his Muslim companion’s method of doing prayers and the ablutions that preceded them: “Before prayers, however, the ceremony of ablution or cleansing is observed, that is, the washing of the head, the hands, arms, feet, and limbs. But since there is no water to be had in the desert, they are permitted to use the sand of the desert for the purpose. The manner in which this ceremony is performed is certainly rather comical, but ‘Mohammed Bey Gambar’ himself lived in the desert, and dedicated or consecrated the desert sand to this use. This ceremony is performed as follows: The Moslem sits down, pushes his chalat and shirt sleeve above the elbow, dips the outstretched hand into the sand, then withdraws it and rubs his face, his ears and his head; then after dipping his fingers into the sand again he rubs his arms, legs and feet. After repeating his ‘Bis milla’ several times, and closing with ‘La Allah,’ the ‘ablution’ is completed.”24 On his way, Bartsch encountered a group of Mennonites travelling in the opposite direction. These families had broken with Klaas Epp and were now immigrating to America. Bartsch was able to persuade his drivers to delay their departure long enough to worship and visit with his Mennonite friends before they departed.

In 1889, Franz Bartsch decided to retire from his BFBS work because bouts of ill health and rheumatic attacks prevented him from conducting protracted journeys in the cold climate of Siberia as required by the job. His brother Johannes was also suffering from increasing illnesses and retired the following year.25 He moved with his family to the Mennonite colony at Aulie-Ata, and a few years later, to the United States.26 But both in Siberia and in Central Asia other Mennonites whom the Bartsch brothers had recruited and trained continued the work of selling Bibles for several years to follow. In Aulie-Ata, a revival of faith in a time of economic hardship had resulted in a new missionary zeal among the Mennonites to win their Kazakh neighbours to Christianity. In his history of the Great Trek, Fred Belk notes that young people were the first to attempt to become conversant with the Kazakh religion, noticing that those Muslims referred to God by the Persian term “Kudai” rather than the Arabic “Allah.”27 He also mentions the work of Johannes and Franz Bartsch, observing that by “becoming quite involved in teaching the natives, [Franz] gained for himself a profound understanding of many aspects of theology.”28

In her analysis of Mennonite encounters with Muslims in imperial Russia, Aileen Friesen has rightly concluded that “many Mennonites showed a level of indifference to the religious identity of their Muslim neighbours.”29 The story of the work of Johannes and Franz Bartsch with the British and Foreign Bible Society in selling Bibles in vernacular languages to Muslim groups in Central Asia is an exception to that general observation. Their spiritual convictions led them to join the efforts of others in this transnational, transdenominational organization committed to Bible translation and distribution. However, this commitment was slow to develop. Franz Bartsch’s book, with its infrequent references to Muslims, demonstrates that Mennonite awareness of their Muslim hosts and neighbours was largely eclipsed by concern for their own community. Instead of exploring aspects of the religious beliefs and practices of the Muslims around them, Mennonites were taken up with theological disputes and divisions related to the teachings of Klaas Epp. It was only after they had separated themselves from Epp’s group that the Bartsch brothers truly focused on the work of the Bible Society. A contemporary of theirs, Heinrich Dirks (1842–1915), was the first missionary sent overseas by the Mennonite church in Russia to work in a region of Sumatra in 1869 with Muslim and other populations.30 But unlike Dirks, the Bartsch brothers were not commissioned by a Mennonite church but rather entered ministry on their own initiative. Their encounters with Muslims as they travelled through Central Asia as immigrants and as colporteurs constitute an understudied chapter in the history of Mennonites in Russia.

Alan M. Guenther teaches history at Briercrest College and Seminary. He developed an interest in the history of Islam when he lived in Pakistan for four years.

- An earlier version of this article was published as “Mennonites among Muslims,” Saskatchewan Mennonite Historian 12, no. 2 (2006): 7–10. ↩︎

- James Urry, “‘Servants From Far’: Mennonites and the Pan-Evangelical Impulse in Early Nineteenth-Century Russia,” The Mennonite Quarterly Review 61, no. 2 (1987): 216. ↩︎

- Reports of the British Foreign Bible Society 7 (1822): 20–21. ↩︎

- Urry, “Servants From Far,” 217. ↩︎

- Urry, “Servants From Far,” 218. ↩︎

- Reports of the British and Foreign Bible Society 78 (1882): 131. ↩︎

- Franz Bartsch, Unser Auszug nach Mittelasien (Halbstadt, 1907; reprint, North Kildonan, MB: Echo-Verlag, 1948), 30. ↩︎

- Hermann Jantzen, Im wilden Turkestan: Ein Leben unter den Moslems, 3rd ed. (Giessen, Basel: Brunnen-Verlag, 1992), 18, 24. ↩︎

- Jantzen, Im wilden Turkestan, 42–43. ↩︎

- Jantzen, Im wilden Turkestan, 37. ↩︎

- F. Bartsch, Unser Auszug, 51. ↩︎

- Jantzen, Im wilden Turkestan, 25–26. ↩︎

- Jantzen, Im wilden Turkestan, 55. For more details, see Martin Klaassen Diary: November 1852 – June 1870, August 1880–October 1881, trans. Esther C. Bergen (Winnipeg, 1993), 235. Copy obtained from Victor G. Wiebe, Saskatoon. ↩︎

- F. Bartsch, Unser Auszug, 57. ↩︎

- Fred Richard Belk, The Great Trek of the Russian Mennonites to Central Asia, 1880–1884 (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1976), 123. ↩︎

- F. Bartsch, Unser Auszug, 62. ↩︎

- Johannes Bartsch, “Reminiscences of a Bible Colporteur,” Herald of Truth, Oct. 15, 1903, 330. ↩︎

- J. Bartsch, “Reminiscences of a Bible Colporteur,” Herald of Truth, Oct. 15, 1903. ↩︎

- Reports of the British and Foreign Bible Society 79 (1883): 108. ↩︎

- Reports of the British and Foreign Bible Society 84 (1888): 146. ↩︎

- Reports of the British and Foreign Bible Society 81 (1885): 112–115. ↩︎

- Reports of the British and Foreign Bible Society 86 (1890): 112–116. ↩︎

- Reports of the British and Foreign Bible Society 83 (1887): 137. ↩︎

- Johannes Bartsch, “Reminiscences of a Bible Colporteur,” Herald of Truth, Nov. 12, 1903, 362. The reference to Muhammad as payghām bar is to his role as messenger or prophet, one who brings a message or payghām. ↩︎

- Reports of the British and Foreign Bible Society 87 (1891): 117, 137. ↩︎

- Shortly after his arrival in the States, Johannes Bartsch published his history of the church, Geschichte der Gemeinde Jesu Christi, das heißt: der Altevangelishen und (Elkhart, IN: Mennonite Publishing Co., 1898). He discusses the trek to Central Asia in pp. 136–141. ↩︎

- Belk, Great Trek, 146. ↩︎

- Belk, Great Trek, 146. ↩︎

- Aileen Friesen, “Muslim-Mennonite Encounters in Imperial Russia,” Preservings, no. 26 (2016): 26. ↩︎

- Alle Hoekema, Dutch Mennonite Mission in Indonesia: Historical Essays (Elkhart, IN: Institute of Mennonite Studies,2001), 86–90. ↩︎