A Critical Gaze: Daniel Schlatter and Mennonite-Nogai Relations

James Urry

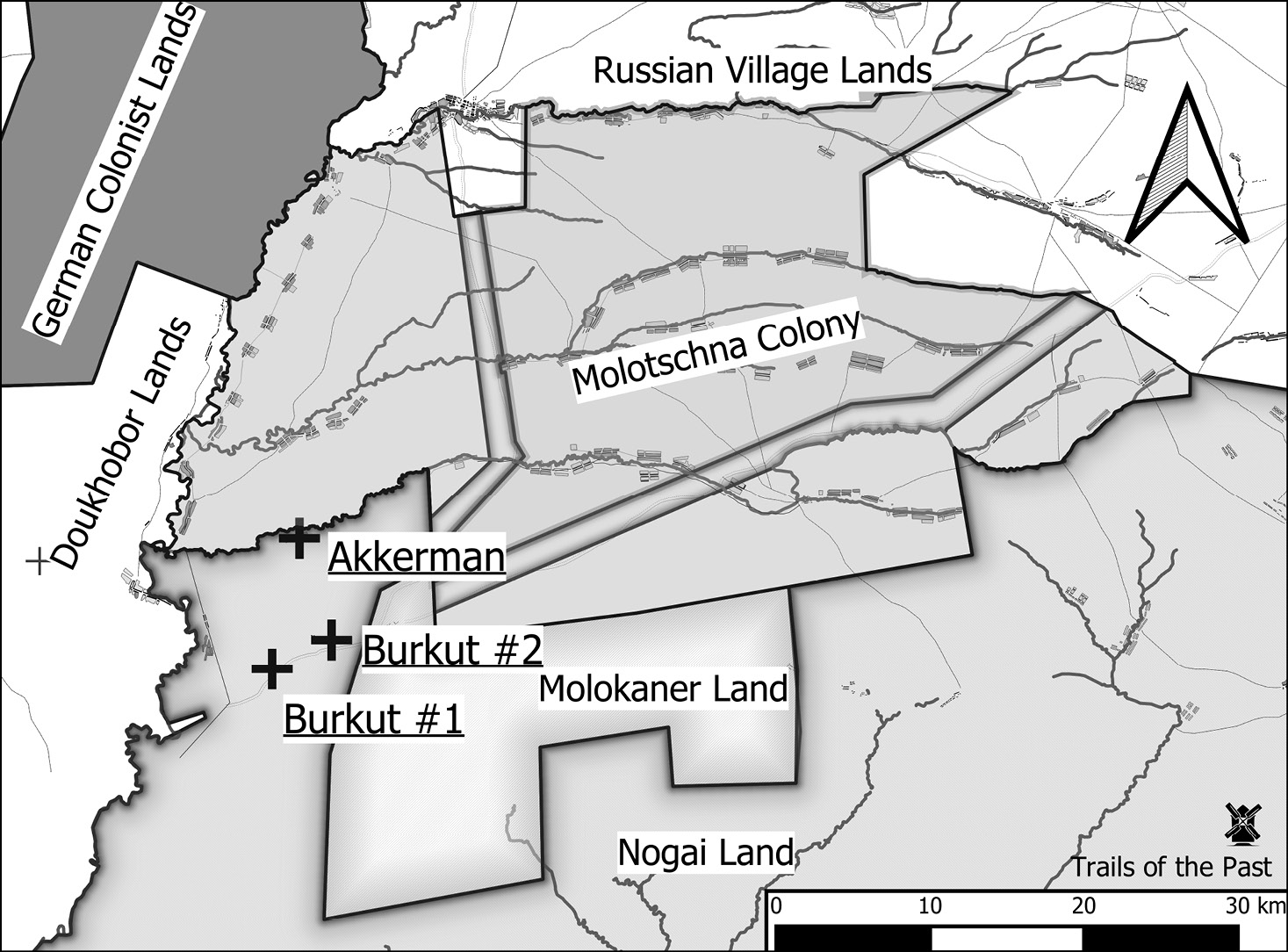

During the first half of the nineteenth century numerous outsiders visited the Mennonite colonies in southern Russia (present-day Ukraine). These visitors included members of other religious faiths and experts on agriculture and economy, mostly foreigners but also Russian government officials.1 Most visits were brief in duration and visitors usually were shown only positive aspects of Mennonite industry and achievements. Only occasionally did visitors comment on Mennonite relations with their non-Mennonite neighbours. A notable exception is Daniel Schlatter (1791–1870), a Swiss missionary to the Nogai Tatars, a semi-nomadic Muslim people living close to the Molotschna colony. Schlatter first came to southern Russia in 1822 and made two subsequent visits until 1828. During his time in the region Schlatter interacted with not only Nogai but also with their Mennonite neighbours, especially Johann Cornies (1789–1848). Cornies was the leading Mennonite in the region in control of the economic development of the colony and neighbouring groups. He had a particularly close relationship with the Nogai, neighbours of the Molotschna Mennonites. Both Mennonites and Nogai were involved with sheep herding, at this point the major source of economic enterprise, as well as horse raising, and Cornies attempted to change their ways.2 After he finally returned home to Switzerland, Schlatter wrote a lengthy account of the Nogai which included comments on Mennonite-Nogai interrelations.3

Life and Work

Schlatter was born into an established merchant family in St. Gallen, Switzerland.4 A number of his relatives, particularly his aunt Anna Schlatter-Bernet (1773–1826), were closely involved with the Swiss and South German Pietist movement. After working in the family business, Schlatter decided on mission work through his contact with the Basel Mission Society. In early 1822 he left St. Gallen to journey to Russia and begin work among a Tatar group. At this time other missionary societies, such as the Edinburgh Missionary Society, were working among Tatar and other Muslim communities.5 His journey took him through the city of Altona, where he met Jacob van der Smissen (1782–1832), a member of a wealthy Mennonite trading family, who provided him with introductions to Prussian Mennonites and even to Johann Cornies.6 Members of the van der Smissen family exchanged letters with Schlatter’s aunt long before he left Switzerland. Schlatter spent time with Prussian Mennonites and gained knowledge of their beliefs and practices.7 While in Prussia, Schlatter gathered information on Mennonites who had emigrated to Russia, a movement that continued at the time of his visit.

On reaching southern Russia he first visited Chortitza. Proceeding to Molotschna he remarked on the variety of German colonists and other groups in the region, including Russians, Dukhobors and Molokans.8 Mennonite villages were “distinguished by their good construction and obvious prosperity, significantly ahead of those [other German colonists] on the right bank of the Molochnaia [River].” After having reached the Mennonite village of Ohrloff, located near the Nogai Tatars, he was uncertain as to how he would be received or how he could begin his mission work.9 He had undoubtedly been directed to Ohrloff to meet Cornies, whose extensive contacts with the Nogai included trading horses and using them as shepherds for his large flocks of sheep. Schlatter’s first visit was short, as in late 1822 he went back to Switzerland, but he returned in early 1823 and stayed until late 1826. He spent most of his time in the Russian empire living among the Nogai, but he often visited Mennonites. In 1825 Cornies wrote to a friend, reporting that Schlatter “dressed like a Tatar,” and visited them in Ohrloff “every Sunday.”10 When Schlatter returned in 1827 it was again for a brief period, as ill health forced him back to Switzerland in 1828.11 He would never returned to Russia.

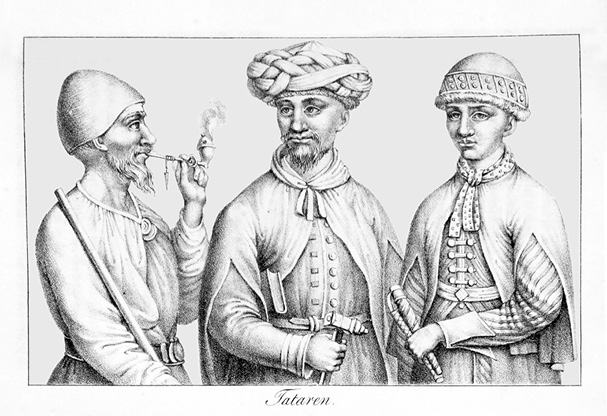

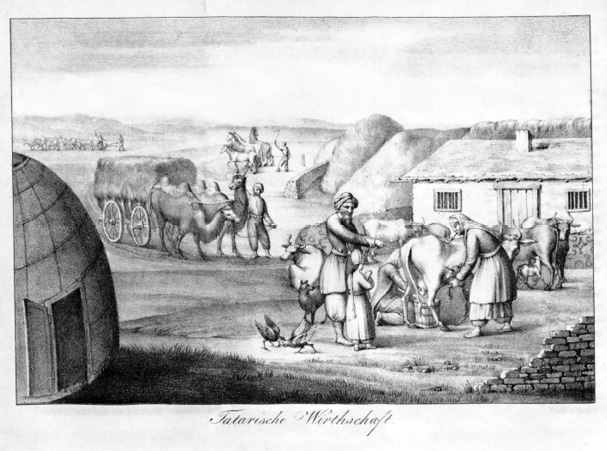

Cornies introduced Schlatter to a local Nogai, Ali-Ametov, who permitted Schlatter to live in his outbuilding in a nearby village. In return Schlatter worked for Ametov, caring for his horses and cattle while also performing various other menial tasks. Through this work Schlatter experienced Nogai life at first hand, gaining a basic knowledge of the Nogai language, including their written script, while acquiring an understanding of their society and customs. He adopted the strategy of wearing Nogai dress, and in 1823 an English mission journal reported that Schlatter lived “in a stable with their horses – drinking mares’ milk, and eat[ing] horse flesh.”12 His own later account, however, details difficulties he encountered in his attempts to be accepted into the Nogai community, as they were suspicious of his intentions. Matters were further complicated as he tried to come to terms with their marriage customs and the ways they treated women.

Mennonites and the Nogai

During his time living among the Nogai, Schlatter continued to visit Molotschna Mennonites, especially Cornies. This is obvious from both Schlatter’s and Cornies’ letters during his time in southern Russia, and after he finally returned to Switzerland. Schlatter also gained access to important senior Russian officials, mostly members of the nobility, who approved of his work and provided support. Cornies undoubtedly assisted him in making these contacts.

In a letter written in 1824, early in his second visit in the Molotschna region, to the English Baptist missionary William Angas, Schlatter was critical of Mennonites: “Your address to the Mennonites (calculated to produce in them both joy and shame) has been much read, and sought after by the settlers here.13 How much can God bring to pass through human means! … How much have the English brethren done, and how little during twenty years past, have the Mennonites done, towards extending the kingdom of God among the Tatars in these parts! They are at present, however, beginning to make a stir among some, (though these are not many, God knows,) whilst others, opposed to the gospel under the garb of a humble piety, lead astray the simple and inexperienced, who, for want of knowing better, will hear of nothing new, and readily believe that Missionary efforts are opposed to the principles of their church, and, consequently, any interest taken in such efforts are regarded in the same light. They imagine, also, that such things would tend to produce a change of sentiment among the churches, as well as endanger the privileges which they already hold from the emperor. But as to the latter of these two suppositions, the reverse is more likely to be the case, as the emperor and his council exhort their subjects, and encourage them to forward the good work, as a thing both praiseworthy and beneficial.14 It is my wish, as well as that of Mr. Cornies and other friends to humanity, that you would pay this colony a visit: so that, under a blessing, you might be a rod to the untoward, an instructor to the ignorant, a strengthener of the weak, and to confirm those still more who stand.”15

In August 1825, Schlatter reported that “Mennonites are too vain of their pious ancestors, as if it were a matter of course that their descendants on that account deserved the name Christians,” although “there are many who lend an attentive ear to the preaching of the word.”16 He later observed: “When a Nogai sees Christians around him who call themselves Greek Orthodox, Armenians, Catholics, Evangelicals, Mennonites, Dukhobors and Molokans, what can he think otherwise than that Christians are, if not worse, then also not better than themselves, whether they are called either Sunni or Shiite?17 In addition, how much more dignified and more sensible, on the whole, is the behaviour and forms of worship of a Muslim than – one may say for the greater part – of those who call themselves Christian, especially in the larger churches! The Muslim also may complain about the decline of religion, but for their part they have not yet fallen in general as far as the Christians.”18

In his book on the Nogai, Schlatter blamed both the Mennonites and the Nogai for the failure to create a better understanding of each other. He wrote: “The fact that for fifteen, indeed more than twenty years, the German settlements close to the Nogai Tatars have exercised so little visible influence on the economic and moral condition of these neighbours is obviously the fault of both parties. The Tatars in general despise everything German and all things foreign and are extremely proud of themselves, as most people on a lower cultural level invariably are. These attitudes on the part of neighbours very often lead to mutual disdain and are the cause of quarrels and disunity, and particularly so since the Nogai allow their cattle to roam over Mennonite land and graze their fill.

“Although the Tatars observe that the Mennonites are more prosperous and live better than they do, they have little inclination to copy the Germans and adopt their lifestyle. Oriental custom and the style of life of the Tatars is too directly opposed to the German way of life to enable them to imitate them or to be attracted to them. Generally, the Tatars do not regard the German style of life as either pleasant or attractive. They say, ‘We aren’t Germans, of what concern are the Germans to us!’ Or, more succinctly, ‘That is not our custom.’

“I personally experienced the resentment of the Germans towards the Nogai on several occasions when I was not recognized as a German. On an occasion when I inspected a garden plot beside the house of an elder or leader of the congregation, a respectable German housewife, who knew no Tatar, attempted to chase me away with Russian swear words. I hesitated to speak German, but I did finally ask her to please treat the Tatars in a more pleasant manner. Granted, the patience of the Germans is put to severe tests when the Nogai come calling, because their snoopiness is very evident, and they cannot be readily turned away.

“As far as morals are concerned, one may observe that in general they still have a good example in the Mennonites; however, the bad is more obvious to them than the good and tends to set the greater example. In Tatar villages lying closest to German villages one can hear the Tatars singing about harlots in broken German and they reveal that the song has been explained to them. The Mennonites do not set a good example to their non-Mennonite neighbours. The frivolous among them are more talkative and active than their religious representatives. The conduct of the Germans to the Tatars does not convey respect and love. The Nogai are treated in a crude manner as recompense for their lack of respect towards the Mennonites. Many appear to believe that the Tatars are a forlorn people, deserted by God and beyond the pale. Even their outward appearance strikes the Mennonite, dressed in the old German style as he is, as repugnant in the same way as does the French or English style of modern dress. He regards the former as a blind heathen and the latter as a child of the world and the anti-Christ. The Mennonite – but others as well – thinks he has reason enough to believe that he can ridicule the Nogai but has no idea that he too is just as backward in many ways from other peoples’ perspectives. However, it is not only contempt but also fear which prevents closer social contact and the possible influence of the German on the Nogai. Every honest, unbiased German colonist, however, has to admit that he has no reason to be afraid of the Nogai even if, here and there, the occasional Mennonite horse has been stolen by them.

“It must, however, be admitted that the Germans in general are much more pleasantly inclined towards the Nogai than are the Russians. Likewise, the Tatars hold the Germans in far higher esteem than the Schlatter’s book provided new insight into the relationship of the Nogai with neighbouring Mennonites.Russians. This is partially based on religious grounds: the religious service of the Germans is simple while the Greek [Russian Orthodox] service is all about pictures and ceremonials and thus in sharpest contrast to the simple and un-ceremonial worship prescribed by Islam.

“The proximity of the Germans has exerted some influence on the Nogai. Very little of this is obvious, however, and a valid comparison would require much more information pertaining to the circumstances and facts of the larger context. Presumably, the Nogai have acquired a greater love of agriculture based on their proximity to the Germans; in particular they now practice the planting of rye. In addition, they have improved the style of their houses as well as their farm implements and forms of animal husbandry, etc.

“There are some Germans who take a sincere interest in the fate of the Nogai and demonstrate empathy for their welfare. Also, they employ more and more Nogai for the hay harvest, at threshing time and as shepherds. The fact that they give the Nogai short rein is obviously based on many personal experiences. As the saying goes, ‘You give a Nogai a finger and soon he will go for your hand and then your head as well.’19

“The development of all good things in life can never be measured in giant strides. In the course of time the Germans will reduce their prejudices and their general disdain [for the Nogai]. However, the same cannot really be expected of the Nogai as long as they remain under the influence of their [Muslim] leaders.”20

An Unorthodox Missionary

Schlatter was always short of money, as his endeavours were mostly funded by himself and supporters. He was forced to borrow money, including a “long-term loan” from Cornies, but was then faced with repaying his debts.21 He was never, in any formal sense, a missionary attached to any religious group or mission board, although one did attempt to make him one of its missionaries. This was the English Baptists who, through William Angas, had been active in German-speaking areas of continental Europe since 1820.22 Angas established contacts with Mennonites in the Netherlands and Prussia.23 He believed Schlatter could become a missionary supported by the Baptists.24 In 1827, before he returned to Russia, Schlatter travelled to London to meet with English Baptists in order to gain financial support. But the meeting did not go well. Angas wrote that the “circumstances” for providing support for Schlatter “proved inauspicious” and after “due inquiry and several conferences” with him, “the negotiation was terminated.”25 Schlatter would later write of his encounter: “Baptists, of whom there are a large number in England, have much in common with Mennonites, but differ from them in that the adults at baptism are completely immersed under water wearing white shirts, for which large pools are built in their churches. In country areas baptism also happens in rivers. Furthermore, unlike the Mennonites, they are zealous followers of the doctrine of predestination. They are very keen on the outward signs of baptism and the Lord’s Supper, meet very often, and pray seriously and a great deal for an unusually long time. Even though they pray very seriously, I could not help but be impatient with their pagan babble and by my thoughts of hypocrisy.”26

Another factor in his lack of organizational support was that for all his time among the Nogai Schlatter had not produced a single convert. A report on Schlatter in about 1826, corrected by Cornies, stated that he did “no proselytizing among the Nogai” but instead his aim was merely to establish “how he can influence Muslim people and their rulers and lead them to true culture.”27 This might best be interpreted as a “civilizing” objective that involved the Nogai changing their way of life and improving themselves as Muslims without necessarily converting to Christianity.28 Ahead of his visit to London in 1827, a letter from Ali-Ametov, the Nogai who had employed Schlatter and provided him with shelter, was published by the Baptists and enthusiastically reprinted by other missionary groups.29 They all appear to have interpreted Ali’s letter as a sign of his conversion to Christianity; however, Ali declared himself to be a Muslim who appreciated Schlatter even though he had been taught from his youth to hold Christians in “as little [esteem] as possible.”

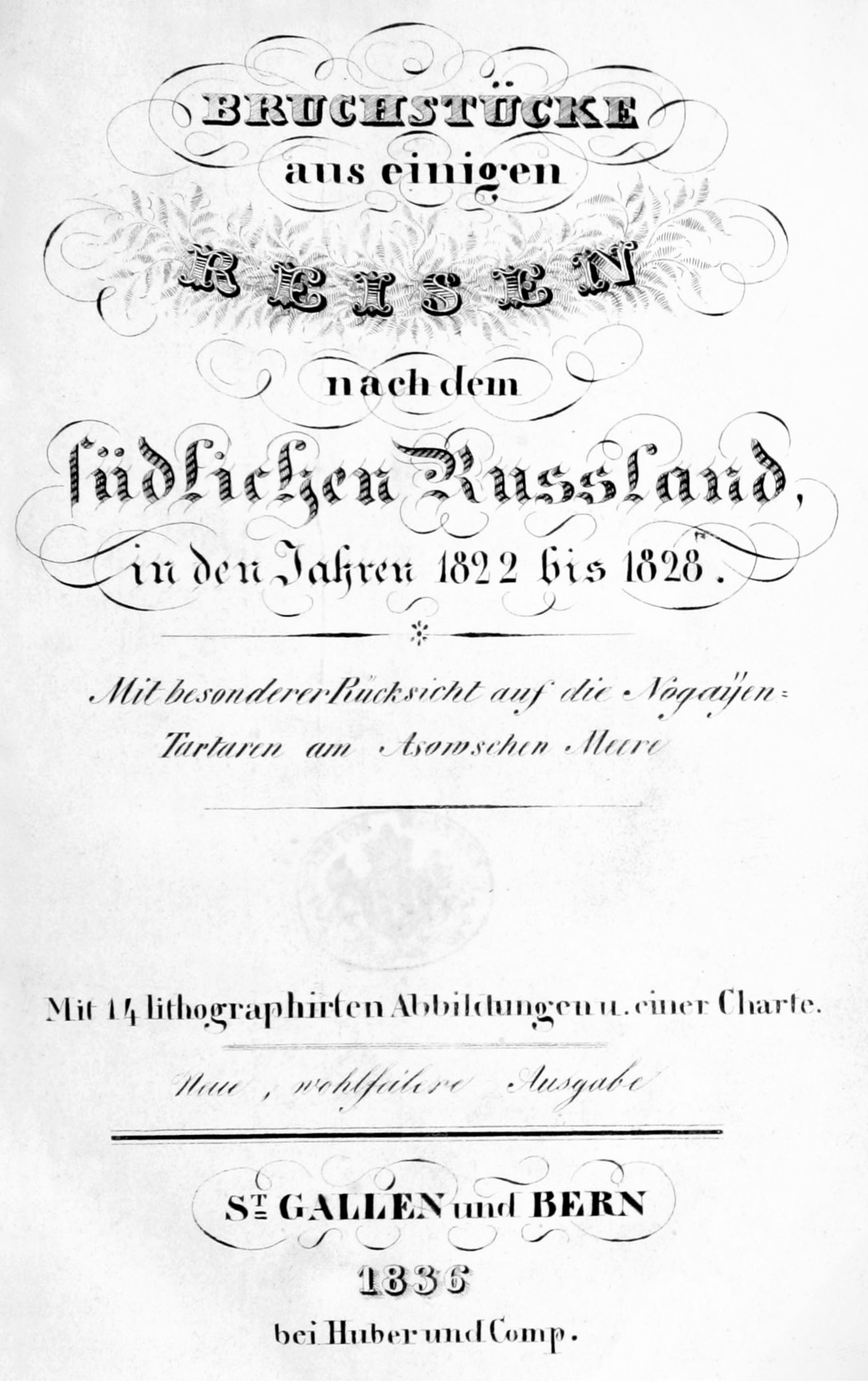

(DANIEL SCHLATTER, BRUCHSTÜCKE AUS EINIGEN REISEN (BRITISH LIBRARY))

In many ways Schlatter was a highly unorthodox missionary. A French reviewer of Schlatter’s book noted that his “mission” strategy appeared to involve spreading “the light of civilization among” the Nogai “not by preaching … dogmas that they would not have understood, and which they would have obstinately rejected, but by putting before their eyes a practical model of the Christian virtues, and by striving to improve, as much as it would be in him, their physical and moral state.”30 Schlatter’s activities once he returned for the final time to Switzerland from Russia in 1828 may best be understood in relation to his increasing rejection of established Christian churches, their dogmas, and even the value of missionary endeavours. In St. Gallen Schlatter re-entered commerce and married; the couple had one son who was named Abdullah after the son of his Nogai friend, Ali. Abdullah would become a merchant operating in Russia and Turkey.31

In about 1826 Schlatter stated to Cornies that he had “never belonged to the Reformed church” in St. Gallen “into which I had been born, though it was not my choice,” and therefore he reserved the right to reject any church whose membership required him to follow “principles I do not accept, from whose precepts I have distanced myself, and against which I must openly speak.”32 In 1832, he joined his brother-in-law Stephan Schlatter in forming a new religious group separate from the established Reformed church. But his attempts to distribute a pamphlet on the principles of the new group in the city was met with “protests and consequently rejection.”33 The city authorities, dominated by the Reformed Church, considered all non-conformist religious groups “sects” and some, like Schlatter’s, were called Wiedertäufer.34 Schlatter certainly believed in adult baptism but did not insist on rebaptizing any who joined his group. His followers refused to take oaths and there was also a concern with non-resistance. Stephen Schlatter had refused military service and had been given prison terms as a consequence.35 All attempts to gain official recognition proved difficult and it was not until 1864 that the St. Gallen authorities recognized the small congregation as a legal entity.36 A congregation descended from the original church still exists as the “Free Evangelical Church” at Goldbrunnen and its website contains an account of its history and beliefs.37

Conclusion

Schlatter continued to correspond with Cornies after his final return to Switzerland. He sent Cornies a copy of his book and Cornies’ letters often contained news of the Mennonites, other German colonists, and the Nogai.38 Cornies also reported the death from cholera of Schlatter’s friend Ali in 1831, when the pandemic swept across Russia and the rest of Europe.39 The last recorded exchange between them that is available was in 1837.40

Schlatter’s book provides an important account of Mennonite-Nogai relations as viewed by an outsider, but one with an ability to look at the neighbours from an informed and critical standpoint. He spoke German and Nogai and had an understanding of both the Muslim and Christian faiths. It is interesting to speculate that although Schlatter remained a Christian after his return to Switzerland he may have been influenced by some aspects of the Mennonite faith while in Russia.

James Urry is a prolific writer of Mennonite history and a retired professor from the University of Wellington in Victoria, New Zealand.

- On early religious links with British Quakers and other evangelicals, see James Urry, “‘Servants From Far’: Mennonites and the Pan-Evangelical Impulse in Early Nineteenth-Century Russia,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 61, no. 2 (1987): 213–27. Most of the other experts came later, after the 1830s, and were not involved with religious issues. ↩︎

- See John R. Staples, “‘On Civilizing the Nogais’: Mennonite-Nogai Economic Relations, 1825–1860,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 74, no. 2 (2000): 229–56, and for the wider context his Cross-Cultural Encounters on the Ukrainian Steppe: (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003). ↩︎

- Daniel Schlatter, Bruchstücke aus einigen Reisen nach dem südlichen Rußland, in den Jahren 1822 bis 1828. Mit besonderer Rücksicht auf die Nogayen-Tataren am Asowschen Meere (St. Gallen: Huber, 1830). Another edition was published in St. Gallen and Berne in 1836 with few changes. The texts of both are available on Google Books and excerpts relating to Mennonites can be found at https://chort.square7.ch/Pis/Schlat.pdf. ↩︎

- See entry in Historisches Lexikon der Schweitz at https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/049218/, and Ursel Kälin, “Die Kaufmannsfamilie Schlatter: ein Überblick über vier Generationen,” Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Geschichte 48 (1998): 391–408. ↩︎

- M. V. Jones, “The Sad and Curious Story of Karass, 1802–35,” Oxford Slavonic Papers 8 (1975): 53–81; Hakan Kirimli, “Crimean Tatars, Nogays, and Scottish Missionaries,” Cahiers du Monde russe 45, no. 1/2 (2004): 61–108; Thomas O. Flynn, “Scottish Missionaries of the Edinburgh Missionary Society and Independent Scottish Bible Missionaries (1802–35) in the North Caucasus,” chap. 5 in The Western Christian Presence in the Russias and Qājār Persia, c.1760–c.1870 (Boston: Brill, 2016). ↩︎

- “Biography of Daniel Schlatter…with revisions in Cornies’ hand,” in Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe: Letters and Papers of Johann Cornies, ed. Harvey L. Dyck, Ingrid I. Epp, and John R. Staples, eds., vol. 1, 1812–1835 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015), 50. The editors have dated this as “probably 1826.” Cornies and van der Smissen were known to each other and even met, see 142, 146, 243–45, 263–64, 408. ↩︎

- Schlatter, Bruchstücke aus einigen Reisen, 14–16. ↩︎

- His account of the Dukhobors published in his book has been translated into English with critical comments at http://www.doukhobor.org/Schlatter.html. ↩︎

- Schlatter, Bruchstücke aus einigen Reisen, 28. ↩︎

- Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe, 1:34. ↩︎

- See Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe, 1:161, 169. ↩︎

- Missionary Register…of the Church Missionary Society 12 (1824): 35. ↩︎

- The “address” mentioned here may be a pamphlet Angas wrote, An die Aeltesten, Lehrer und Mitglieder der (Danzig, 1823); see https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Angas,_William_Henry_(1781–1832)&oldid=144715. ↩︎

- This comment refers to the support of Tsar Alexander I for the Russian Bible Society and missionary work by foreign religious organizations. On Mennonite involvement see Urry, “Servants From Far.” ↩︎

- Daniel Schlatter to W. H. Angas, Ohrloff, April 27, 1824, The Baptist Magazine 16 (1824): 545–46; also in the The American Baptist Magazine 7 (1827): 83–85. ↩︎

- Daniel Schlatter, letter from Ohrloff, August 1824, The Baptist Magazine 17 (1825): 409; also in Missionary Register 13 (1825): 395. ↩︎

- Sunni/Shi’a is the major divide in Islam. For a recent account see Laurence Louër, Sunnis and Shi’a: A Political History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020). ↩︎

- Schlatter, Bruchstücke aus einigen Reisen, 151. ↩︎

- Variations of this saying occur in many languages. In German, “Gib jemandem den kleinen Finger, und er nimmt die ganze Hand”; in Russian, the hand and arm are removed to the elbow! ↩︎

- Schlatter, Bruchstücke aus einigen Reisen, 359–69; this translation is by Professor Jack Thiessen and the late Professor Al Reimer with minor changes. ↩︎

- Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe, 1:158, 190. On Cornies’ financial loans, see John R. Staples, “Johann Cornies, Money-Lending, and Modernization in the Molochna Mennonite Settlement, 1820s–1840s,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 27 (2009): 109–27. ↩︎

- See his biography in Benjamin Swallow and W. A. Blake, Biographical Memoirs of Deceased Baptist Ministers from the Year 1800 to 1850 (London: Benjamin Green, 1850), 13–28. ↩︎

- F. A. Cox, Memoirs of the Rev. William Henry Angas: Ordained a ‘Missionary to Seafaring Men’ (London: Thomas Ward, 1834), 97. Angas met with opposition from some Mennonites who suggested that “English Baptists were only a better sort of Roman Catholics” (his emphasis), 81. ↩︎

- The Baptist Magazine 15 (1823): 490. ↩︎

- Cox, Memoirs of the Rev. William Henry Angas, 97, 117. ↩︎

- Schlatter, Bruchstücke aus einigen Reisen, 427. ↩︎

- Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe, 1:50. This appears to be a draft biography written for a Russian government official when Schlatter was contemplating settling in the Empire. ↩︎

- The translation of the report might be inadequate here, but unfortunately no German text is available. ↩︎

- The Missionary Register…of the Church Missionary Society 15 (April 1827): 217–18; The American Baptist Magazine 7 (June 1827): 187–88; Journal des missions évangéliques 2 (1827): 66–70; reprinted yet again in News from Afar, or Missionary Varieties, Chiefly Relating to the Baptist Missionary Society (London: The Baptist Mission Society, 1832), 87–88. ↩︎

- “Le véritable missionnaire, Daniel Schlatter,” Nouvelle revue germanique 4 (1830): 395. ↩︎

- Ursel Kälin, “Die St. Galler Kaufleute Daniel und Abdullah Schlatter in Südrussland,” in Fakten und Fabeln: Schweizerisch-slavische Reisebegegnung vom 18. bis zum 20. Jahrhundert, ed. Monika Bankowski, Peter Brang, Carsten Goehrke and Robin Kemball (Basel and Frankfurt am Main: Helbing & Lichtenhahn, 1991), 335–63. ↩︎

- Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe, 1:49. ↩︎

- Jahrbücher der Stadt St. Gallen…1835–41 (1842), 184; Grundlage einer christlichen Gemeinde in St. Gallen (St. Gallen: Wartmann, 1838). For an attempt to refute the new movement see Gedanken und Andeutungen über Kirche, Kirchenzucht, Abendmahl und Separation (St. Gallen: Zollikofer’schen Offizin, 1838). ↩︎

- Jahrbücher der Stadt St. Gallen…1835–41, 180–86; see also Jolanda Cecile Schaerli, Auffaellige Religiositaet: Gebetsheilungen, Besessenheitsfälle und schwärmerische Sekten in katholischen und reformierten Gegenden der Schweitz (Hamburg: Diserta Verlag, 2012), 297–99, 386. ↩︎

- See his entry in the Historisches Lexikon der Schweitz. ↩︎

- “Beschluss betreffend die Dissidentengemeinde in St Gallen,” Gesetzessammlung für den Kanton St. Gallen 1 (1868), 485. ↩︎

- https://www.goldbrunnen.org/1447-revision-v1 ↩︎

- See for instance Cornies’ long letter of 12 March 1830 in Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe, 1:187–90. ↩︎

- Cornies to Schlatter, 11 March 1833, in Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe, 1:316. ↩︎

- Cornies to Schlatter, 22 July 1837, in Transformation on the Southern Ukrainian Steppe: Letters and Papers of Johann Cornies, vol. 2, 1836–1842 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020), 61–62. ↩︎