My Unlikely Namesake: A German POW in the East Reserve

Ernest N. Braun

Historically, the Mennonites of Manitoba’s East Reserve have been conscious of its unique position as an island surrounded by the outside world. There is a Low German phrase that applies: “Woa’re se de Welt mett Pankuake too-henje,” translated as “where the world is hung shut with pancakes.” In this case the Clear Springs settlement, occupied by Ontarian and British homesteaders, immediately abutted the reserve to the northeast. North and west of the East Reserve was Métis reserve land. Part of the land east and south was also Métis land with scattered French-Canadian settlements. The story of East Reserve Mennonites is interlaced with encounters with these neighbours. However, there was another neighbouring community, localized and very short-lived, that few people know: a temporary work camp at La Rochelle three miles due west of the reserve. It was occupied in 1945 by two hundred prisoners of war (POWs) from Germany.1

The quartering of hundreds of German-speaking enemy soldiers on the farm of the French-speaking Catellier family just a few miles from the East Reserve was an interesting bureaucratic decision. The juxtaposition of German military prisoners and German-speaking Mennonite pacifists created some unusual consequences, one of which was to affect my entire life.

The arrangement in La Rochelle was based on demand for farm labour in the new sugar beet industry, which was tied to the sugar refinery in Winnipeg run by the Manitoba Sugar Company. At that time, sugar beet cultivation was heavily dependent on manual labour. Since thousands of Manitoba men had enlisted in the armed forces, there was a shortage of labour for thinning, hoeing, and harvesting the beets. Yet sugar was in even greater demand, and the industry was growing. To resolve this problem, captured German soldiers were trucked into the area around the communities of La Rochelle, Dufrost, and Ste. Agathe to work for minimal wages. A compound was constructed north of what is now Provincial Trunk Highway 23 on the Catellier farm, between the gravel road (now PTH 59) and the Rat River, where a bend in the river created a peninsula, largely a meadow. Here they lived in tents behind a barbed-wire fence patrolled by armed guards, and worked long hours in the surrounding beet and corn fields. The farmer paid $2.50 per day for the work, of which the prisoner received 50 cents. The government took two dollars for “room and board.”2

Mennonite men were drafted into the military but often received a farm exemption. For this reason it was inevitable that Mennonites would end up interacting with the POWs. On the Catellier farm the lead hand was a Mennonite, as was the Manitoba Sugar Company truck driver who drove the men from farm to farm and in fall hauled the harvested beets to what was known as the “sugar factory.”

One Mennonite farmhand noticed the restricted diet of the hard-working POWs.3 As a result, he and his wife invited those men who wanted additional food, and who were willing to take the risk, to come after dark and have supper with them. During part of the season this meant sweet corn on the cob. The men would crawl under the barbed wire to have a late meal with the family. Twenty years later I heard enthusiastic descriptions of the taste of that corn, and the warmth of the kitchen where Mennonite High German encountered standard European High German, causing some amusement on the POW side.

When I began to research the work camp in the early 1990s, the former POWs did not remember the name of the Mennonite farmhand who had welcomed them, making it difficult for me to track the man down. Well over a year elapsed before I found a clue to the name and, fortunately, a telephone number in Edmonton. I wondered how I would broach the topic, and how I would clinch the identification. Then I remembered the amusement of the POWs at the antiquated German that the Mennonites spoke so confidently. Armed with that knowledge, I called the number out of the blue, and asked the man whether he had ever worked on the Catellier farm in La Rochelle while the POW camp was there. Somewhat cautiously, he said yes. Then I asked whether he spoke German, and he said yes again. I warned him I was about to ask an unusual question: “If you were going to serve some food to a visitor to your home and wanted to say ‘Don’t be shy, help yourself’ in German, what would you say?” He replied, “Well, I would say, ‘Sei nicht blüde.’” I replied, “You’re the man I want to talk to. I have a friend in Germany who would like to thank you personally for the sweet corn you fed him and his fellow inmates in the 1940s. Can I give him your phone number?” He agreed, maybe not entirely believing that this would happen. What the Mennonite man did not understand, and what I did not tell him, was that in modern High German “sei nicht blüde” does not mean “don’t be shy”; it means “don’t be stupid”! No wonder the POWs were somewhat taken aback, and amused.

(MANITOBA, PRISONNIERS DE GUERRE ALLEMANDS ENVOYÉS EN HOLLANDE, V-P-HIST-03381-27)

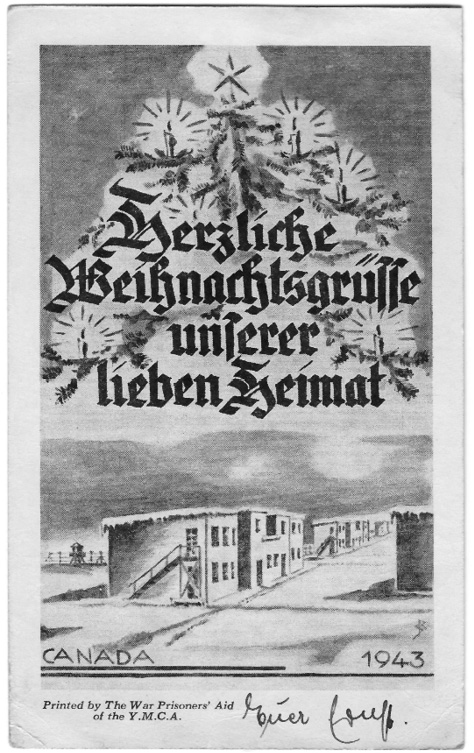

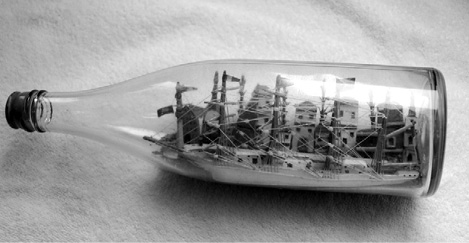

There was also a Mennonite from Grunthal who drove truck for Manitoba Sugar. He was not eligible for the draft because years earlier in a lumber camp he had lost his trigger finger, so during the war he worked part of the year in the agricultural industry. It did not take long for him to connect with the prisoners since he was fluent in German, and moreover bore a quintessentially German surname. Not surprisingly, in the La Rochelle camp there was a prisoner with the same surname, and the two struck up a friendship. This resulted in some unusual interaction. The prisoners, who had nothing but time on their hands during their off hours, had begun to exercise some entrepreneurial talents, one of which was to produce postcards and market them through the YMCA’s War Prisoners’ Aid effort. Some of these original postcards are now in the hands of farmers in Ste. Agathe and Glenlea. Selling artwork was another way some men raised money.4 A more unusual enterprise was making ships in bottles. This was complicated since clear wine bottles needed to be obtained, and the only way was to have a sympathetic outsider smuggle them into the camp, such as the Mennonite truck driver. Moreover, the endeavour was of no use unless those ships in bottles could be sold. Again, it was the Mennonite truck driver who took the bottles to Winnipeg after establishing connections to sell them. He then brought new bottles and the money back into camp on the next trip. To this day, occasionally such a ship in a bottle will show up in a Winnipeg antique sale.

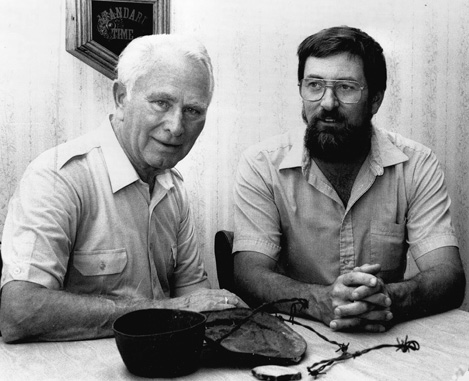

What does all this have to do with me? The story is too long to be told here in detail, but the long and short of it is that one of the POWs in La Rochelle carried the name Ernst Braun, a corporal from Nürnberg who befriended the Mennonite truck driver, my father’s brother, Peter Braun.5

Some background may be helpful to give the larger context for this improbable scenario. In 1941 Adolf Hitler attempted to help the Italians with their African campaign by creating the Afrika Korps under “Desert Fox” Erwin Rommel, to establish a second front which would weaken the British forces that were pressuring the Italians. This initiative, code-named Operation Sunflower, was treated with considerable fanfare in Italy, even to the extent of getting the Vatican to have a commissioning ceremony where Pope Pius XII blessed the German troops before they left for Tripoli in early 1941. The media happened to cover the event and a photo was taken of the pope speaking with a few Wehrmacht soldiers on their way to Africa. That photograph was published in Der Spiegel in October 1997.6 As coincidence would have it, one of the soldiers shown conversing with the pope was Ernst Braun.

Braun had served on the Eastern Front (where he narrowly escaped death from a random shell near the Mennonite colonies in Ukraine) as well in several other countries before being recruited for the Afrika Korps. After many months in that theatre of war, on May 28, 1942, he was captured by the British some twenty-five kilometres south of Tobruk while on a reconnaissance mission, and taken through Egypt to various camps in Palestine along with hundreds of other captured German and Italian soldiers. After several hearings Braun was transferred to Camp 310. The camp prisoners were shortly evacuated south through the Suez Canal, but he had learned about their destination and decided he did not want to go there. Braun intended to escape once the camp was empty. He hid under the floor of a tent for three days until a new contingent of soldiers, Italian this time, was brought in after new British victories in North Africa. He revealed himself to the new group, which was delighted by his subterfuge and feted him. In the meantime, Braun heard through the POW grapevine that a new POW camp was being constructed near the mountains in Alberta, Canada. He made up his mind that if he had to spent the rest of the war as a prisoner, he wanted to go there. When the Italians were evacuated within a day or two, Braun discovered the destination was not Alberta, so again he decided to hide, this time behind a false wall in the long multi-stalled latrines. The next day another group of Italian POWs arrived. Braun revealed himself to them, but this time he was betrayed to the camp commandant, probably inadvertently. Braun was promptly ordered to appear before the commandant, who congratulated him on deceiving authorities twice, but sentenced him to twenty-eight days of solitary confinement. Then, with some smugness, the commandant stated that Braun would be sent so far away that he would never rejoin the German forces. On August 17, 1942, the prisoners, Braun among them, were marched to the Suez Canal and loaded onto the SS Pasteur, a troop ship of the Royal Navy, and sent to Alberta.

It seems that throughout his life, Onkel Ernst, as we refer to him even today, was always a step ahead. As he boarded the ship with thousands of other POWs, he anticipated the realities of what lay ahead. Knowing that the lower decks of the ship would certainly become unbearably hot, he slowly worked himself backwards in the queue until he was right near the end of the seemingly endless line of men being loaded onto the Pasteur. As a result he got to be housed on the topmost deck, which provided not only comfortable living conditions but also a good view as the ship travelled more than halfway around the world. In addition, this position offered some hope of survival in the event of an attack by German U-boats, one of the greatest dangers of the trip, whereas should the ship be torpedoed by his countrymen, anyone in the lower decks was doomed. Onkel Ernst promised himself that he would see Rio de Janeiro, and to that end volunteered temporarily for slop duty. Unimpeded by confinement, he managed to experience a view of the magnificent city glistening in the sunshine.

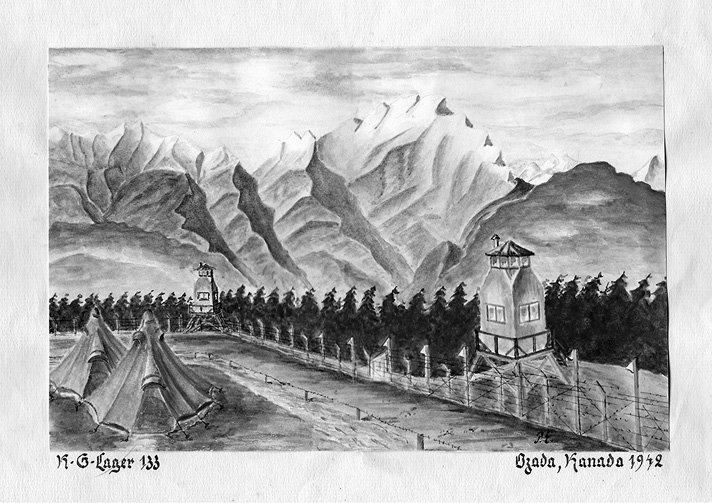

After a month at sea aboard the overcrowded Pasteur the prisoners arrived in Halifax on September 18, and were loaded directly onto a special closed train bound for Ozada, Alberta. Windows could only be opened a crack, and armed guards stood at each end of the car with two more nearby; even the bathroom doors were removed. At stops, the train was surrounded by soldiers with fixed bayonets.7 After five days of breathing stuffy air, Onkel Ernst disembarked and inhaled the pure mountain air; he would remember that moment for the rest of his life.8 From the station they were marched to a temporary tent camp, Camp 133, near Ozada, which was on the Stoney Nakoda Indian Reserve, just south and west of the intersection of the Trans-Canada Highway and the Kananaskis Trail (Highway 40). They would stay there until the permanent Camp 133 being built in Lethbridge was completed, in late November. When we visited the former camp site in 1991, stone rings were still visible in the grass. These rings had been placed on the tent flaps to prevent the penetrating November wind from lifting them and chilling the soldiers. Handmade light fixtures also lay in the grass. The tent camp was guarded by a company of the Veterans Guard of Canada, as were most of the POW camps, since younger able-bodied soldiers were mostly in Europe.9

On December 1, 1942, the entire camp population was moved to Lethbridge, one of the two largest camps in Canada, where Onkel Ernst spent the next two and a half years behind barbed wire. Lethbridge was built to accommodate 12,500 POWs in dormitories each housing 350 men, and included two large recreation halls, six mess halls, education huts, and workshops. Prisoners could play sports or musical instruments. Soccer tournaments and orchestra performances were regular events. In winter some played hockey. The POWs also hosted craft sales featuring paintings, postcards, and ships in bottles.

When the war ended in May 1945 the detainees were given a choice: stay interned in Lethbridge or work in a labour camp for minimal wages. Onkel Ernst chose the labour camp and on June 18 ended up at La Rochelle, where he came to know my uncle Peter. Peter used his beet run to Winnipeg as an opportunity to supplement the POWs’ rations with sausage, flour, and other provisions he could acquire in those difficult times. It was through Peter that Onkel Ernst met my father, who would correspond with him regularly from 1947 onward. After spending the summer in various farm activities, from hoeing sugar beets, working in the corn fields, harvesting wheat, and topping and piling sugar beets in fall, Onkel Ernst was transported by train to Medicine Hat Camp 132 for another five months. Then on February 5, 1946, since he was a prisoner of the British (not Canada), he was transported back to Halifax and shipped to the United Kingdom, where German POWs were forced to provide labour as a form of war reparations. Sent to a farm in Wales, he characteristically forged a personal bond with the farm family for whom he was forced to work, and after the war took his family back there several times to visit. The camp in Lethbridge finally closed on June 30, 1946.

After almost four years of captivity in Canada, Onkel Ernst had accumulated a collection of documents, photographs, and his sketches, which he was forbidden to take with him. With a false bottom in his duffel bag and creative lining in his boots he managed to smuggle some of these back all the way to Germany, where I got to see them twenty years later.

After almost a year in Wales, Onkel Ernst was repatriated to a devastated homeland. The food situation in Germany after the war was dire. Shortages began in May 1945, when the destruction of farmland, livestock, and machinery, plus labour shortages and adverse weather, limited the supply of food available to German civilians to only 1,000 calories a day. Moreover, the practice of shipping goods from occupied countries to Germany had ended with their defeat. This reality was exacerbated by restrictive American food policies for occupied Germany, designed to “have it driven home to them that the whole nation has been engaged in a lawless conspiracy against the decencies of modern civilization,” as President Roosevelt put it.10

As a result of my family’s new connection to Germany, the Canadian Braun family became aware of the need, and when international aid agencies were allowed into the country we regularly sent care packages of food to our namesake family, the earliest arriving while Onkel Ernst was still in captivity in Wales. In 1967, when I visited Germany for the first time, his elderly mother told me that if it had not been for that food, the family would have been starving.

When I was born in late 1947, and the matter of which biblical name I was to bear the rest of my life came up, my mother declared that there were enough Jacob and Peter Brauns already. Dad proposed old Germanic names: Friedrich (Fritz) and Nicolas (Claus). These names did not fly with Mom. The next day, Dad had an idea: the name of his new German friend in Nürnberg, Ernst. Just after my first birthday in 1948 I received a German picture book as a Christmas gift from my Namensvetter (namesake) Ernst Braun, and our lives became intertwined from that moment to this day. My father died tragically in a traffic accident when I was eight years old, and from then on Onkel Ernst took on the role of surrogate father. Each Christmas we had two Christmases: first, the somewhat limited one that my widowed mother could afford, and then the “Onkel Ernst Christmas,” with German chocolate, toys, lebkuchen, and German novelties arriving in a big box a week or two before Christmas and anticipated with great excitement. At the time I did not think having a Christmas package sent from Germany was anything out of the ordinary; as children we accept what happens as normal. Only as I grew up did I realize how rare and precious this experience was. Although he passed away in 1999, we still correspond and visit back and forth with his widow and his family.

In 1967, during my university years, I had the opportunity to experience Germany as a work-exchange student. My namesake, by now a successful businessman in Nürnberg, was delighted to meet somebody from my family for the first time in twenty-two years. While I was there, I asked Onkel Ernst whether he felt cheated having to spend the best years of his life as a prisoner. He was genuinely surprised at my question and made me answer it myself. He said, “You have now been in Germany for months; how many men of my age have you seen?” I suddenly realized that the only men his age were those with missing limbs trying to sell pencils on the sidewalk, or lying shell-shocked in various public places. He added, as I recall it: “I am exceptionally fortunate that I was captured early in the war, and that I was able to serve my time in Lethbridge in a beautiful setting which was really a university, for there was a professor of every discipline in the world in the next barracks, and none of us had anything else to do but learn from them.” He was an extraordinary man, later becoming an authority on the Holy Roman Empire and on Rome itself, which he visited regularly. And wherever he went he always made friends.

For reasons that Onkel Ernst never understood, around 1944–45 all prisoners in the camp received a new Westclox DAX Style 3 pocket watch, which he took home and used for decades until it broke down and was replaced by a wristwatch. Now missing its glass and stem, I proudly display it in my house.11 Onkel Ernst wanted me to have this reminder of his time in Canada after he died, and his widow sent it to me in about 2000. Another poignant reminder of the link between the two Braun families is a 1960 pewter beer mug with the initials “EB” engraved on the lid, one of their most prized wedding gifts, which was gifted to me by the German Braun family in the summer of 2019, since I am now the only member of the family carrying those initials.

Shortly before his death, Onkel Ernst called, and we talked for a while as usual. At the end he thanked me for the good connection we had been able to have. I was a little surprised, but the meaning would soon become clear. Those were his last words to me; a few days later his wife called to say he had just died.

Building a POW camp near the Mennonite East Reserve set up an extraordinary juxtaposition of German soldiers next to German-speaking pacifists. I was fortunate to get to know one of those soldiers. But I did not know the soldier – I knew only the man. After a lifelong friendship with Onkel Ernst, I understood this distinction in a whole new way, and how my life had been immeasurably enriched by the fortunate connection that we shared.

Ernest N. Braun is a retired educator and resides with his wife Doreen on an acreage near Tourond, Manitoba. He devotes his time to researching and writing on topics of local Mennonite history and is co-editor of The Historical Atlas of the East Reserve (2015).

- Other reports indicate that the camp was in operation for several years. My story focuses on 1945. ↩︎

- Chris Teetaert, “German POW Camp Near St Pierre,” Steinbach Online, July 28, 2010, https://www.steinbachonline.com/local/german-pow-camp-near-st-pierre. It is revealing that although the farmer offered to buy the building erected at the camp, the government preferred to bulldoze and bury it. ↩︎

- One POW told me that after the war ended, reports of the treatment received in Germany by Allied prisoners so incensed the British government that rations in Canadian camps were to be reduced to 800 calories a day. Canadian camp administrators objected, and eventually a compromise was reached: German POWs could be fed normal rations provided they served in work camps. ↩︎

- Michael O’Hagan, “Tag Archive | Camp 133 – Ozada,” PoWs in Canada, https://powsincanada.ca/tag/camp-133-ozada/. ↩︎

- This is an abridged version of a more detailed private article I have written with permission from POW Ernst Braun’s family in Germany. ↩︎

- Rudolf Augstein, “Das ist eine Schande,” Der Spiegel, October 19, 1997, 106. ↩︎

- Eric J. Holmgren, “Prisoner of War and Internment Camps in Alberta” (unpublished essay, Edmonton, 1983). ↩︎

- In August 1991, when my brother and I took him back there, he was disappointed with the air quality, but I reminded him that my car had air conditioning, and the 1942 train did not. ↩︎

- Camp Ozada 133 was scenic and prompted several artists among the POWs to sketch or paint the setting. See https://powsincanada.ca/tag/camp-133-ozada/. ↩︎

- Cited in Christopher E. Mauriello, Forced Confrontation: The Politics of Dead Bodies in Germany at the End of WWII (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017), 13. ↩︎

- I have contacted noted collectors and pocket watch experts, but nobody seems to understand why Westclox would donate thousands of these pocket watches to returning German prisoners of war. From the Westclox website it appears this style of clock was not made after 1938, and perhaps sales were interrupted by the war and this was one way of entering the European market and at the same time disposing of old stock. ↩︎