Building Bridges: Mennonites and their Neighbours in Latin America

Kennert Giesbrecht

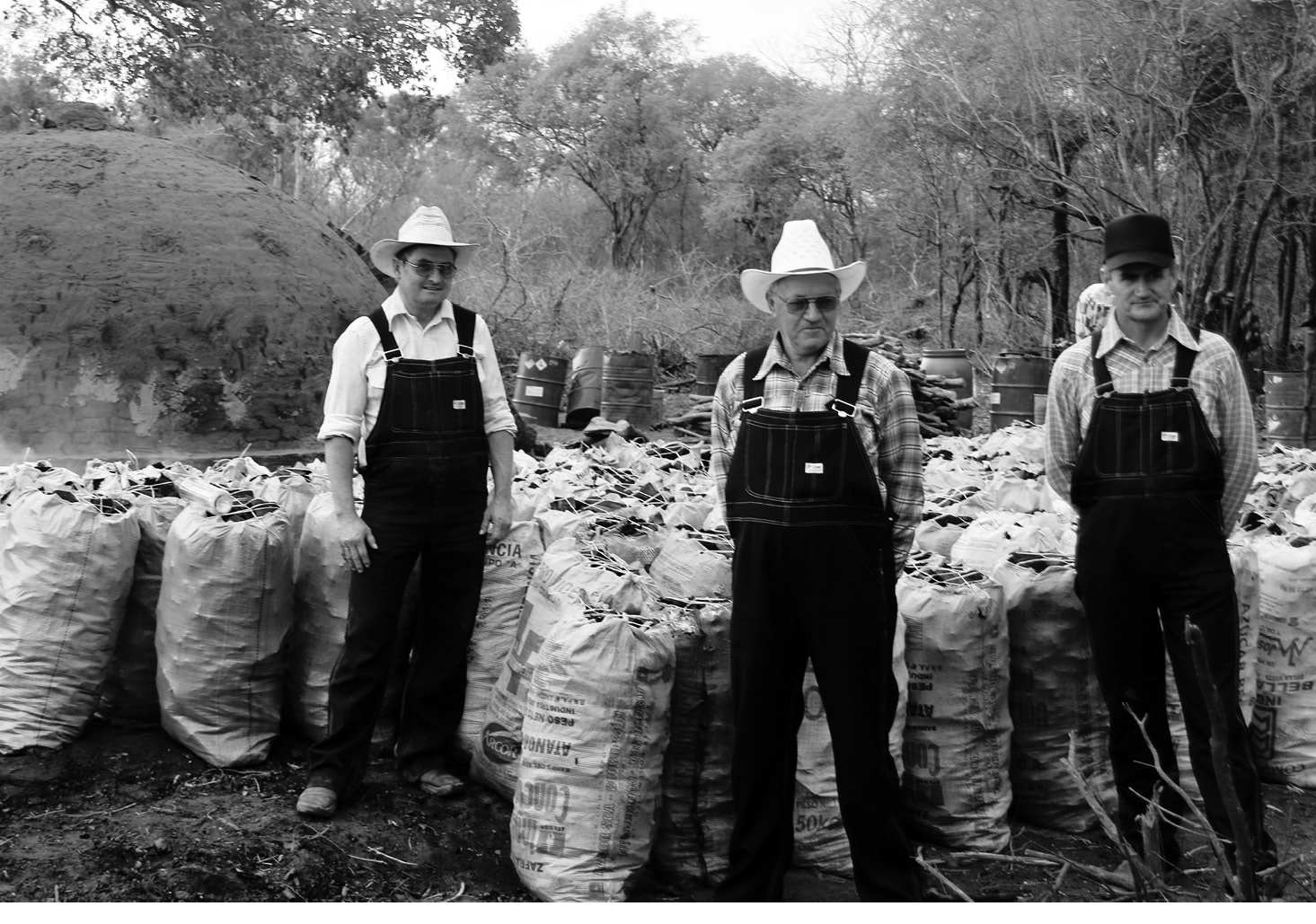

Establishing a new Mennonite colony in Latin America involves a lot of work, hardship, and suffering. Daily life is a struggle for survival: food must be on the table, income is virtually nonexistent, and expenses are huge. Emotions are a roller coaster, up and down, over and around. A good life, the kind of life one dreams of, exists only in the distant future. Help and support make new beginnings in a strange place much easier. When Mennonites in Latin America refer to neighbours, they are usually thinking about people in their own villages. Mennonites don’t spend much time thinking about their non-Mennonite neighbours outside of the colony. And yet their relationships with these neighbours are often critical as they determine how the colony will develop.

Mennonite settlers in Latin America soon notice that their locally born neighbours are important for the life of the colony; financially, the colony could not survive without them. Neighbours, in many cases, offer important advice to help Mennonites establish themselves quickly. I hear this often when talking with settlers in the new colonies. They speak of friendly contacts with native-born residents of the area. They emphasize the importance of positive relationships and speak enthusiastically about how people already living in the towns and settlements around new colonies are willing to work together with Mennonites.

One hears from local residents how important Mennonite settlements are for local economic development. Taxi drivers, business owners, and others outside of the colonies often talk about how eager they are to work with Mennonites. Words like “trust,” “punctuality,” and “honesty” are heard repeatedly in these conversations. I heard these sentiments from Juan, my taxi driver, during one trip to the Bolivian colonies in 2015. As the road was muddy and poor, the drive to Swift Current Colony took significantly longer than we had expected, which gave us time to talk. Juan mentioned how he had come to know Mennonites and how he had worked together with one Mennonite business owner for ten years. “I couldn’t wish for a better patrón,” he said. “He is understanding, pays me promptly, is very hospitable, and always invites me to eat with him and his family. He gives me advice and asks me for advice. He is simply a very good man.”

Not all speak so positively about Mennonites, however. A few years before I met Juan, I was driving in similar conditions, to the same colony, with a different taxi driver. It had rained, the roads were bad, and we had to drive slowly. Jorge also told me a number of good things about Mennonites, but he wasn’t quite as taken with the life and work of Mennonites as Juan. “Never again will I drive in the colonies on a Sunday,” he said. “It is simply too dangerous there for us Bolivians when the young people are on the streets. They stop us, spit at us, say all kinds of nasty things to us, threaten us, and throw mud or sand on our vehicles. No, I don’t want to be in the villages when the young people are on the streets.” While Jorge’s words saddened me, I knew exactly what he was talking about. I had often heard about the problem of young people on the streets, not only from the local residents but also from Mennonites themselves.

Mennonites in Latin America are accused of racism, and I must admit that the accusation is not always undeserved. Since most of the colonies are somewhat isolated geographically, they often function almost as states within a state. They have autonomous administrations, their own schools, and their own laws and rules. This easily leads Mennonites to the conclusion that “nobody can tell us what to do.” There is a certain feeling of power, a sense that they can’t be touched. One often hears Mennonites use disparaging terms about their neighbours. Negative statements like “you can’t teach them anything,” or “they’re lazy and good for nothing,” or “they have no clue how to work and get ahead” are too often heard. Just because people live, think, or do things differently than Mennonites doesn’t mean that they are lazy, useless, and good for nothing. Especially if we want to call ourselves Christians, we should be careful not to look down on other people. In God’s eyes, we’re all equal.

By sharing some examples, I hope to convey the positive and constructive side of how Low German–speaking Mennonites have engaged with their neighbours in Latin America. For this article I will focus on missions and aid work, but there are clearly many other stories that could be told about these interactions.

Paraguayan Engagement

Mennonite colonies in Latin America are generally involved in missions and development work among their neighbours, and Mennonites in Paraguay were intentional about evangelizing their neighbours from the beginning. However, the founders of Menno and Fernheim colonies, the first colonies in Paraguay, did not come to this landlocked country in the heart of South America to engage in mission work. Their needs and concerns in the early years of settlement went in a different direction; their overwhelming concern was simply survival. Often it was individuals who took the initiative to evangelize. As the colonies developed, they became more interested in missions and development work among their neighbours.

Various Indigenous groups lived in the Paraguayan Chaco when the first Mennonite settlers arrived in the late 1920s. Mennonites quickly picked up words and phrases in the languages of their Indigenous neighbours, and some Indigenous people similarly learned Low German. In this way, a hybrid language developed in the Chaco which was a mixture of Low German and local languages. In Menno Colony, the Indigenous people were mainly from the Enlhet group. Over time, many Enlhet became fluent in Low German, and some Mennonites learned the language of the Enlhet so well that they could preach and teach in it. The New Testament was translated into this language, and by now the entire Bible has been translated into Indigenous languages.

Mission work among the Indigenous population of the Chaco led to the establishment of many churches, as some Indigenous people accepted the Christian faith and called themselves Mennonites. Many even took Mennonite names, often of an employer or some other respected person. Since Indigenous people were not registered in the records of the government, they could select any name they wanted. Often siblings would have different surnames, such as brothers Peter Funk and Johann Friesen.

The fact that many Spanish-speaking Mennonite congregations now exist in Paraguay demonstrates that evangelization of their neighbours has become important to many churches and colonies. Missionizing in Indigenous communities began early in the Chaco, led by churches from Fernheim Colony. This was later extended to the local Latin Paraguayan population, and by the 1950s the churches of Menno Colony also actively joined in this effort. In recent decades, mission efforts directed at Indigenous and Paraguayan neighbours have continued to grow. There are more churches and aid organizations that focus on development work, support educational programs, and undertake many other activities in order to help their neighbours.

Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) performed an important role in the formation of a Christian service initiative in Paraguay. Mennonite immigrants from Canada who founded Menno Colony in 1927 were given privileges by the Paraguayan government under Law 514. On the basis of this law, many Mennonites emigrated to Paraguay in the succeeding years and decades, from Canada as well as from the Soviet Union. Paraguay accepted all of them generously, including those who were elderly, ill, or incapacitated. In gratitude for this accommodation from the Paraguayan government, MCC, together with Paraguayan Mennonites, established a thanksgiving project, the relief organization for Hansen’s disease (leprosy) sufferers commonly known as “Kilometre 81” (Km 81). This initiative, named for its distance from Asunción, is as familiar to native Paraguayans as it is to Mennonites. The program had two aims: to assist people suffering from Hansen’s disease, and to plant the ideal of Christian service in local Mennonite congregations.

For decades, the focus of the hospital was on those suffering from Hansen’s disease, who were generally ostracized by society. In recent years there has been increased emphasis on tuberculosis treatment. The “Hospital Menonita” offers people from the region comprehensive medical care, which they receive either free or at low cost. Thousands have been treated here, and many have been cured. People crippled by the disease have received footwear that allows them to walk and to work.

Since its inception in 1951, hundreds of people from the colonies have volunteered at Km 81. Although the hospital was planned and initiated by MCC, Paraguayan Mennonites have been an active part of the program from the beginning, and eventually took over full responsibility for the hospital, and for Hansen’s disease treatment in all of Paraguay. Many of the donations that make the work at Km 81 possible, both in money and in goods, are provided by the colonies.

Organizations like ASCIM (Asociación de Servicios de Cooperación Indígena-Menonita) have undertaken important initiatives among their Indigenous neighbours. This organization aims to support interethnic development work in the Chaco. According to the Lexikon der Mennoniten in Paraguay encyclopedia, it has five main objectives: “(a) to accompany the Indigenous communities in their economic and social development; (b) to support their efforts to secure their land base; (c) to maintain advisory services to support their subsistence on their own soil; (d) to support educational programs to equip the younger members of the Indigenous population with the knowledge and the ability to participate successfully in their new social setting; and (e) to support preventative healthcare and medical treatment in the Indigenous settlements, and to offer medical consultation.” Some of its successes have included helping with the return of 160,000 hectares to the Indigenous people, which allowed for the creation of fifteen new farming settlements for three thousand Indigenous families.

In the colonies of East Paraguay, Mennonites also live in close proximity to their Latin Paraguayan and Indigenous neighbours. Contact with these neighbours has always been more intense and personal than in the Chaco. This is mainly due to the fact that the population density was much higher in East Paraguay. Latin Paraguayans and Indigenous people lived next to and even in the middle of the colonies. People bought and rented land from their Latin Paraguayan neighbours. Over the decades, various aid organizations, often through private initiative, have also been established.

Aid in Mexico

Representatives of the five colonies in the Cuauhtémoc area of Mexico met in December of 2005 in the colony centre in Lowe Farm. The purpose of the meeting had been circulated in advance with a simple question: “Do we want to help in Chiapas?” The answer was clear and came without hesitation: “Yes!” Enrique Letkeman, chair of the relief committee, along with Franz Peters and Vorsteher Peter Enns, showed pictures of the devastation that had recently been caused by Hurricane Stan, and reported on the situation. They shared that the hurricane had brought three days of heavy rain. Large stones were carried along by the rushing water. A river, normally twenty-five metres wide and only a few feet deep, topped its banks and caused devastating mudslides along both sides. Entire residential districts had been washed away or buried. The group had also travelled to Mexicalapa, where, of fifty-two homes, only one tin shack and the church remained. People from this area had never experienced such flooding, and rain-softened dirt slid from the slopes and buried roads and houses.

The representatives at this meeting agreed that they wanted to help. They decided to collect money in the colonies and churches, in order to build homes for the victims of the disaster. This meeting was the beginning of a much longer relief effort in Chiapas by Mennonites from Mexico. They travelled throughout the Cuauhtémoc colonies and reported on the extent of the disaster. It wasn’t long before hundreds of thousands of dollars in aid had been collected. These donations were channelled to a relief committee, which organized and implemented the relief plan in Chiapas, in close collaboration with MCC Mexico.

It is interesting to note how organizations established during natural disasters can end up doing more than just disaster relief. This was the case with the children’s home Brazos Abiertos (Open Arms) in Nuevo Casas Grandes. It started when a group of people from the region around El Valle offered help to Haiti after the earthquake in 2010. The organization created to carry out this work was called Corazones Humanitarios de Chihuahua (Humanitarian Hearts of Chihuahua). When their assistance to Haiti, which consisted mainly of sending relief supplies, was finished, people wanted to continue helping in other areas.

They found need everywhere. It was decided to start a children’s home in Nuevo Casas Grandes. This city is approximately fifty kilometres northwest of the El Valle Colony. The children’s home was dedicated in January of 2016 under the name Brazos Abiertos. Voluntary donations funded its construction. Some thirty farmers from the El Valle area supported the organization with a small portion of their harvest. They committed themselves to give the proceeds of one hectare of cotton (or other crops) to the children’s home project. The farmers received the cost of seed and other expenses from Corazones Humanitarios, but all the profit went to the organization. Business owners and other private donors also supported the project. In this way enough money was gathered to purchase a lot and begin construction.

By the end of July 2017, sixteen children were in Brazos Abiertos. Many were homeless, as their parents, often addicted to drugs or alcohol, were unable to care for them. The work in the facility is mostly done by Mexican women and girls living in the city. A committee from the colonies has oversight and ensures that there are sufficient finances and food to care for the children.

In 1998, Isaac Bergen Thiessen, a missionary from the Mennonite conference of Mexico, established an aid organization named Un Sueño Realizado A.C. (A Dream Come True), in Cuauhtémoc. Bergen initiated this project to help people who, because of a physical or other disability, were unable to find work. A workshop was established, where people with a disability could learn to work with wood or leather or to sew with the help of some employees as well as volunteers. Most of the profits realized from the sale of these goods were then returned to the clients as payment. In addition to the workshop, this organization created several facilities where clients could work at physical rehabilitation in a focused way. People who previously had only been able to crawl or use a wheelchair learned to walk again. In October 2013 this organization was recognized with an award and honoured for its social services by the state government of Chihuahua. At that time it was listed as one of the top five aid organizations in the country.

Another project, Ampliando el Desarrollo de los Niños (Expanding Children’s Development), was initiated by Bergen and the church in Cuauhtémoc. It is also located in the city of Cuauhtémoc, in a low-income neighbourhood. Children here are often alone at home for hours after school because their parents are working. Ampliando el Desarrollo de los Niños addresses this issue by offering an afterschool program; two hundred children receive a meal, some additional instruction, and also help with their school homework. Volunteers run this program.

The building and the dining room they use is at full capacity. As there is still much demand, they plan to add another location, on the second floor of the church associated with this project. Here, another ninety children can be offered meals and care. As Bergen says, “The demand is great. All we need is more facilities, financial support, and volunteers to run the programs.” Bergen led this work until his retirement in 2016; John Loewen took on the task as his successor.

Conclusion

Many other initiatives by individuals or groups from the Mennonite colonies could be added to this list. I have often heard of sewing circles that make blankets, mats, or clothes, or women’s groups that collect clothes, blankets, and shoes to distribute to people in need. Sometimes groups of congregations collect foodstuffs to distribute to victims of famine. Financial donations from the colonies even reach disaster-affected areas in Africa and Asia. MCC alone received more than $100,000 (US) in 2017 from the Mennonite colonies in the Americas when funds were solicited in response to the famine in South Sudan.

Mennonites in the colonies generally are glad to help when they see that their money is used to meet a specific need. For the most part, established colonies can do more for their neighbours than new ones. And that is logical. In the early stages of a colony, it is important to resolve any problems in the community before looking outward. The colony is completely absorbed in its own struggle for survival. Often the burden of debt and payments is so heavy that it is difficult to think of the needs of others. And occasionally there are also people in these new settlements whose own food resources are scarce.

One thing is clear to me: Mennonites rely on their neighbours while establishing a new colony. However, the people around the colony, be they Indigenous or local residents, also eventually benefit from its presence. This kind of mutual benefit often goes unnoticed but shouldn’t be forgotten.

Kennert Giesbrecht is the editor of Die Mennonitsche Post. He grew up in Menno Colony in Paraguay and has travelled extensively through Latin America.