Jacob Penner: A Mennonite Communist

Dan Dyck

In 2000, the city of Winnipeg honoured the late alderman Jacob P. Penner by naming a park after him.1 It very well may be the only park in Canada honouring a communist. Even more unusual, this communist was from a Kleine Gemeinde and Mennonite Brethren background. An immigrant to Canada from the Russian empire, Penner would become a prominent figure in Winnipeg’s civic politics.

Early Years

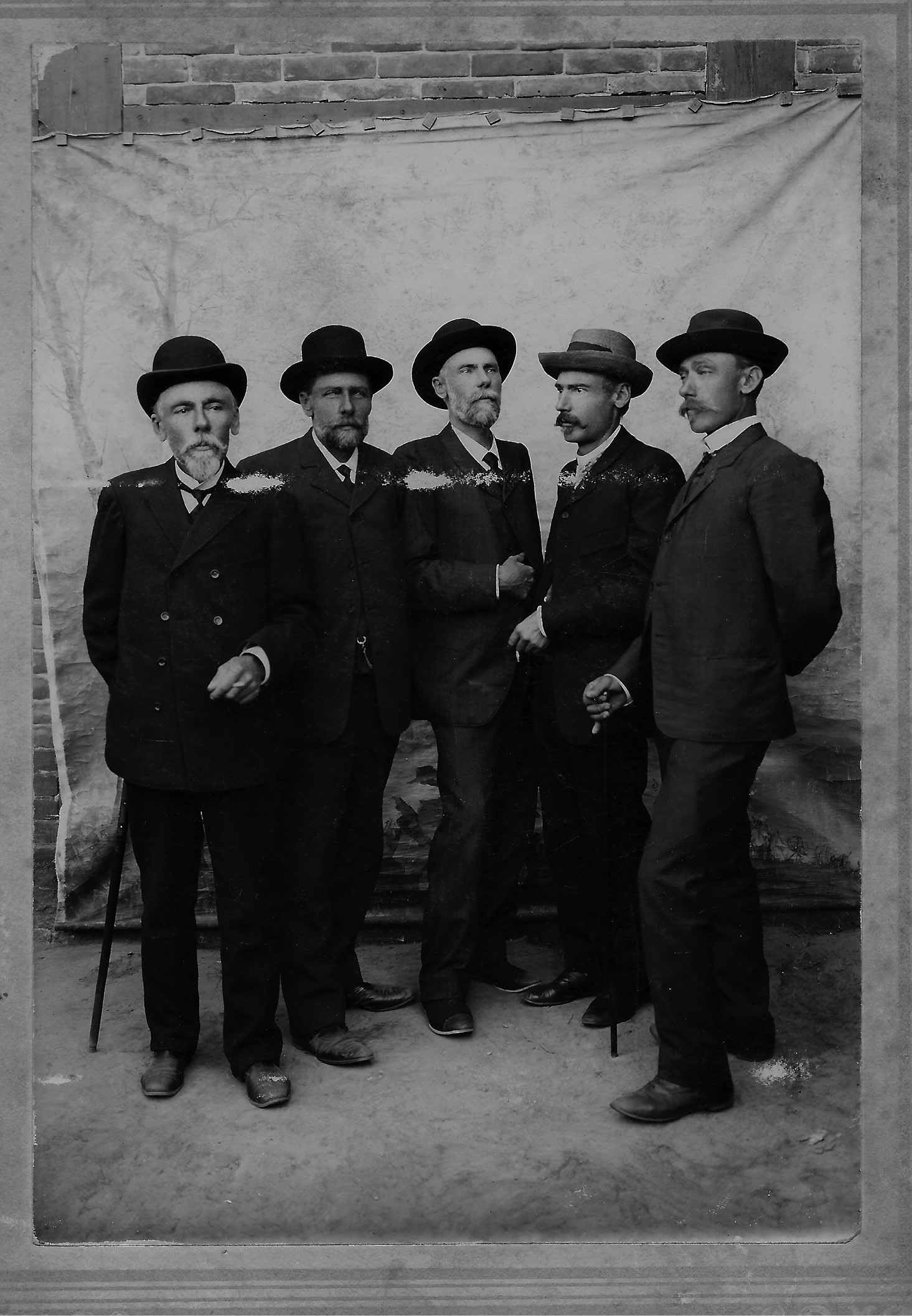

Jacob P. Penner, a small-framed, soft-spoken Russian Mennonite, arrived in Quebec City on August 4, 1904. The mild summer weather likely felt familiar to that of the home he had just left in Ekaterinoslav (present-day Dnipro, Ukraine). He had been born in 1880 in the western borderlands of the Russian empire. His great-grandfather, Peter P. Penner (b. 1799), settled in the Molotschna colony, in the village of Prangenau, where he became a respected Kleine Gemeinde minister after joining the church in 1835.2 Peter’s son, also named Jacob, moved from Prangenau to Friedensfeld, near Nikopol, in 1867, where he and his wife, Helena (Dueck), established a large estate. Jacob had been active in the Kleine Gemeinde church before the move, having placed fourth in a ministerial election in neighbouring Neukirch with twenty-seven votes out of 110.3 During their time in Friedensfeld, the Penners would eventually join the Mennonite Brethren church.4

The Penner family thrived in Friedensfeld until a downturn in the rural economy jeopardized their standing. Having purchased many thousands of acres on credit, the senior Jacob Penner found himself unable to pay back the loan. According to his nephew, Johan W. Dueck, “The mortgage holders from whom Uncle Penner had bought the land threatened to repossess it, if it was not paid for by a set deadline. Through all this trouble and worry it happened that Uncle Penner died of a heart attack after he had lain speechless for three or four days.

“After Uncle Penner’s death the mortgage holders took the land, livestock, equipment and so on, all of which had also been given as security. So the Penners were completely bankrupt and came into poverty. Aunt Penner died some years after this bankruptcy.”5

Jacob Penner’s eldest son, Peter D. Penner, was a man who chose to follow his own path. He married Margaretha Unger, who was the daughter of Abraham Unger (1825–1880), the early Mennonite Brethren leader from Einlage, in the Chortitza colony. Personal faith was important to Margaretha. Peter, however, was said to have held no strong religious convictions.6

Margaretha shared stories with her granddaughters about having a pleasant early married life. Russian servants did the housework while she cared for her children and enjoyed passing the time with needlework. Wendy Dueck, a great-niece to Jacob P. Penner, said, “My mother was quite close to her grandmother, and she told my mother that when she was first married and had Jacob and Peter and Helen and the children, she said, ‘All I had to do was take care of my babies. I didn’t have to do any cooking or washing or cleaning.’”7

Margaretha’s own family had wealthy origins. Her father was the first Mennonite to construct wagons with spring suspension, and his son Abraham (1850–1919) was credited with enlarging his father’s wagon factory in Einlage. Except for Margaretha, the Unger clan chose to stay in Russia, a decision that would have dire consequences for the elder Unger’s son Abraham and grandson Abraham. They were tortured and murdered by anarchists on the night of October 28–29, 1919.8

Peter D. Penner had an entrepreneurial bent and was apparently comfortable with risk. In 1894 he mortgaged the family estate to buy a larger one 250 kilometres southeast, near Rostov in the Don River valley. How he managed to purchase this estate, given his father’s bankruptcy, is unclear. Wendy Dueck said anecdotally that Peter, “being the eldest son, had taken advantage of his dad’s money and invested it here and there without a lot of family discussion.”9 More loans were made to purchase machinery and hire labourers to bring the land into agricultural production. Four years of drought further compromised the situation. Although the family records are not entirely clear, it appears that drought led to foreclosure. The year of foreclosure is not known.

Peter then acquired a flour mill in Riga, Latvia, in 1900, where the family minus eldest child Jacob P. relocated. The once wealthy family proceeded to fall deeper into hard economic times.10 However, Wendy Dueck notes that in a photo including all the married siblings, which was taken sometime after the family relocated to Riga, Peter’s wife, Margaretha, is “wearing a lovely [light-coloured] dress and all her sisters and sisters-in law are wearing black. I think she had already moved on to her Riga status.”11 By 1900, Riga was a well-established port city and had become “one of the most industrially advanced and economically prosperous cities in the entire Empire.”12

While the family established itself in Riga, Jacob P. Penner created a life in Ekaterinoslav. He had already done a four-year course in normal school, starting at age twelve, and taught for a year, which he disliked. He was assigned to Ekaterinoslav after studying land surveying and joining the civil service. Penner became politically active after witnessing the brutality of the Russian political system when a group of Cossacks beat, without mercy, striking workers at the Briansk Metal Works in 1902.13 This event convinced him to become involved in an underground reading circle. As his granddaughter Cathy Gulkin describes, “When Jacob was a young man in Russia, he began associating with a circle who were reading and discussing Tolstoy. Which eventually led to the study of Marx and Engels and to Jacob’s conversion to socialism and communism from Christianity.”14

Penner chronicled this conversion in his own words: “When I was a boy in Russia I came in contact with the Marxists and became immediately interested in their viewpoint – participated in underground, secret meetings in the forest on the outskirts of the city, protected by a sentry.” He also recalled, “My parents – very religious, orthodox Mennonites – were greatly disturbed and alarmed that I would land in the clutches of the regime. Father was always very much opposed to my views . . . My views did not break up the family, but our relationships were strained, quite strained sometimes, because I would always start a discussion with my socialist viewpoints.”15 Though he rejected a religious path, he acknowledged that science and religion were both valid ways for humans to understand the world. This understanding was part of his identity in a deeply rooted way. He seemed to have had a passion for the ideals of the social gospel imprinted on his soul.

Fearing that their son’s growing profile as a social justice activist and revolutionary might land him in hot water with the tsarist regime, Penner’s parents pressured him to leave the empire. He resisted. Though the family desperately needed to move to find financial stability, Penner’s parents refused to emigrate without him. He finally acquiesced. The failure of their flour mill in Riga and the danger of Siberian exile – a likely risk for their politically active son – spurred the family’s migration to Canada.

Move to Canada

After landing in Quebec City in August 1904, the Penner family travelled to Winnipeg. Having left farming years earlier, they stayed in the city. What resources they had were invested in a rooming house which they established as a bed and breakfast to host rural Mennonites travelling to Winnipeg on business. It was largely run by Margaretha and her daughters. Wendy admired Margaretha for adjusting to this new life without servants. As Wendy remarked, “Guess who was cooking and cleaning.”16

With no Mennonite churches established at the turn of the century in Winnipeg,17 the family connected with the First German Baptist Church. Whether Penner ever attended services here with his family is unknown. “[Later] in the 1920s there were quite a few of the Penner family, siblings, children, and so on, who were members,” said Wendy. The family’s partial Mennonite Brethren roots likely helped them find a home in this church, as German Baptists had some influence on Mennonite Brethren doctrine and practice in Russia.18

Penner’s first impressions of Canada are captured in a letter to a friend in Odessa. He commented on the huge “American-style” retail organization called Eaton’s – a large department store where he would later briefly work as a clerk. The letter reflects his recognition of the exploitation of workers in Winnipeg at the behest of wealthy businessmen.19

Penner’s early years in Manitoba were beset by homesickness and ill health. In a 1907 letter to an unnamed uncle still in imperial Russia, he apologized for not writing sooner and reported that “from the beginning I was not well here.” The letter described the pros and cons of his new homeland. The advancement of telephone communication, he lamented, would “do away with the writing of letters.” Nonetheless, he noted the difficult social aspects of isolated rural living, with farms being so far apart. Penner noted the many good sides to his life in Canada, but observed that “we have had a hard time adjusting to the new circumstances, customs, and views – indeed to Americanism.”20

Shortly after his arrival in Manitoba, Penner attended Mennonite Collegiate Institute (MCI) in Gretna, where H. H. Ewert was principal. He was at MCI from September to November 1904, since he needed a Canadian certificate to teach. This certificate enabled him to teach in an Altona school from December 1904 to June 1905.21 Ewert was a strong and demanding leader with an uneven temperament who headed the school for many years; he was well regarded and respected by Penner.22

Penner later recalled: “Quite often Ewert would invite us to his house to have dinner there. And there was a lot of conversation. Ewert and the students were very interested in the conditions in Russia. They dwelt on the socialist movement in Russia a lot. They knew I was a confirmed socialist. They were not horrified, but they doubted the correctness of my viewpoint that the tsarist regime was coming to an end. They did not believe that at all. The students were entirely opposed to the idea of socialism and so was the teacher. But surprisingly Ewert would not express himself to that effect, and I noticed he was quite a leftist.”23

A Partnership

Jacob felt most at home in Winnipeg’s North End, where many eastern European immigrants lived. Their cheap labour helped to build the “Chicago of the North,” as Winnipeg was often called. Jacob saw the toll of factory work on impoverished families whose parents were made to put in long shifts and six-day weeks for low wages. He made connections with labour activists and with advocates for the poor, and attended organized labour meetings. It was at a lecture by the American political activist Emma Goldman, organized by the Winnipeg Radical Club, that he met his future wife, Rose Shapack, likely in March 1908.24

Jacob’s background provided for an immediate bond with Rose, who was born in Odessa around 1890. Rose (registered as Rachel with Manitoba Vital Statistics) was raised in the village of Zakharovka. Her mother Eva died when Rose and her identical twin sister Bertha (also called Beckie) were toddlers. Their father, Chaim Ben Shapack, remarried Sima, a young widow who favoured her own child from a previous marriage, Anuta, and then later Lillian, conceived by Ben and Sima’s union.25

Chaim’s children by his first marriage were routinely not given fresh bread, which was reserved only for Anuta and Lillian. Rose recalled having her first taste of fresh bread one Easter when the twin sisters were on the run during an anti-Jewish pogrom, in which the local Christian population ransacked Jewish homes and businesses. A Christian man took them in and fed them some bread.26

Around ages eight or nine, the twins were sent to work as chocolate dippers and candy wrappers in one of Odessa’s famous candy factories. In 1905, during a time of civil unrest and political upheaval, they participated in the famous Odessa general strike, and observed aspects of the sailors’ mutiny that was commemorated in the classic Sergei Eisenstein film Battleship Potemkin. The strike was crushed.27

Rose quickly became active in Winnipeg’s Jewish radical and cultural life. With her brother, twin sister, and others, they formed the Winnipeg Jewish Dramatic Club. Meanwhile, Jacob became a literature agent for the Socialist Party of Canada (SPC).

Being partnered with Rose would have exposed Jacob to anti-Semitism in Winnipeg. This type of prejudice would have been familiar to him. The violent persecution of Jews in the Russian empire was one reason why some chose to immigrate during the thirty-year period prior to the First World War. Three hundred arrived in Winnipeg in 1882, and by 1911 Winnipeg’s Jewish population had grown to almost 9,000.28

Prejudice in Winnipeg was not limited to Jews. Ukrainians, Poles, and Latvians who lived almost exclusively in Winnipeg’s North End, where the Penners resided, faced great disparities in living conditions compared to people of British origin. The rate of infant mortality in the North End, for example, was 372 per 1,000 births, well over three times the rate in the city’s predominantly British south side.29

Newcomers of eastern European origins were often racialized in the news. George Fisher Chipman published two articles in Canadian Magazine attacking the character and intelligence of “foreigners” living in Winnipeg’s North End. These newcomers had only a few defenders, such as J. S. Woodsworth, who operated the All People’s Mission. He pleaded for help and tolerance for the new arrivals.30 At a meeting in 1912 Penner met Woodsworth and later came to greatly admire this “Methodist with a mission” who preached the social gospel.

Jacob and Rose were united in their compassionate support of vulnerable people and supported political action that sought equal human rights for the working class and those of foreign cultures. Whether one’s motives for social reform and basic human rights were driven by religious convictions or political ideology did not seem to matter to Jacob; he understood both motivations. Even though he and Rose were self-declared atheists, as their son shared, “Our family lived the social gospel.”31

Jacob and Rose had an atypically long engagement for the time, characterized by romantic strolls in Winnipeg’s Stella and Kildonan parks, attending operatic and theatrical events, and boating on the city’s rivers and streams. In a move that was highly unconventional at the time, in 1912 they gathered friends to announce their commitment to one another without any form of religious ceremony. Much later, on January 9, 1930, they were officially married in a ceremony officiated by the Methodist minister and labour rights activist Reverend William Ivens, “for the sake of the children.”32

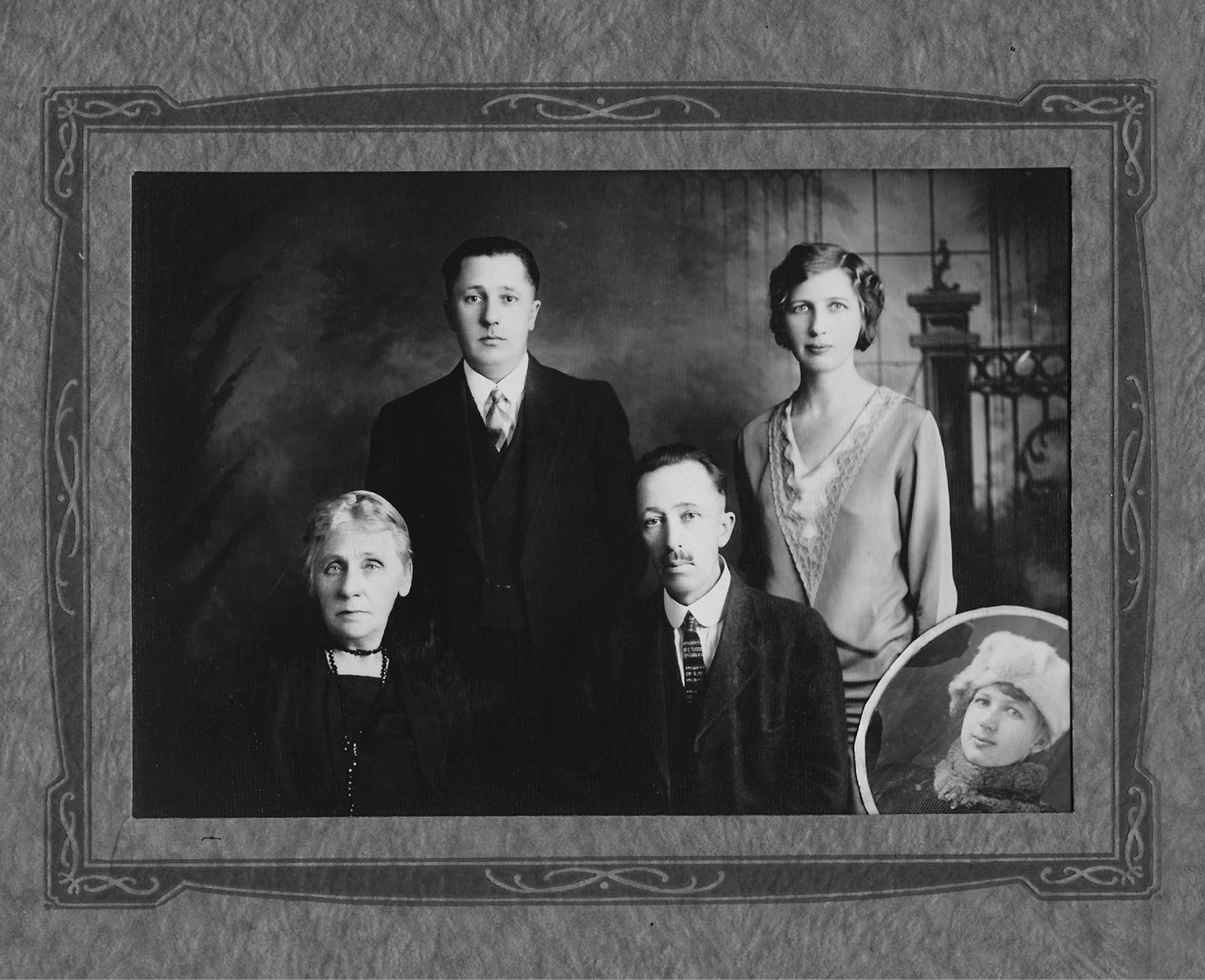

The late 1910s and 1920s were busy times for Jacob and Rose. Seven children arrived. A daughter, Norma (1918), lived just over one week.33 Next came Walter (1919), Norman (1921), and Alfred (1922). Alfred had Downs syndrome. He was eventually institutionalized at a facility in Portage la Prairie where he died at age eleven. Jacob’s son Roland recalled, “He was sent away because the neighbours petitioned to put Alfred away out of fear of their own children . . . Grossmomma [Margaretha Penner] got him a new sailor suit and a toy train, because he was going away on a train.”34 Twins Roland and Ruth arrived in 1924. Roland would become a lawyer, and later Manitoba’s attorney general.

Like many families of the time, the Penner parents saved money by growing a garden. Jacob, in particular, had a green thumb. As Roland recalled, “We always had a garden; he was a good gardener – corn, potatoes, vegetables, flowers in the front yard. Verbena was one his favourites, and all of us had to take turns to weed the lawn – there was not one weed in our lawn.”35 Paid by piecework, Rose and the children would supplement the family income by wrapping candies at home for the Galpern Candy factory.

The family became known in the neighbourhood as “the Red Penners.” Whether in defiance or in embrace of the label, some of the Penner children and their friends fell into the practice of raiding local market gardens. When tomatoes were in season, the youngsters, who called themselves “the Red Raiders,” would go out armed with a paring knife and a pre-sliced loaf of the locally famous City rye bread,36 appetites at the ready. On one occasion, they liberated watermelons and cantaloupes from a producer, loudly proclaiming, “The Red Raiders are here!” The owner stood up from behind his hiding spot and the chase was underway. Though they escaped, word did get back to Jacob, who “sternly made it clear that this activity was now at an end, as indeed it was.”37

Activism

In his adopted homeland of Canada, Jacob Penner would contribute to a growing labour rights movement through his political activity. Though Mennonites could be uncomfortable with Penner’s politics, he remained connected to the community. H. H. Ewert, of MCI, made visits to Penner at the Trades and Labour Hall during events that eventually led to the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike. The purpose of these visits is not known.38

As a literature agent for the Social Democratic Party of Canada, which he co-founded in 1910–11 after breaking with the SPC, Penner imported books that championed Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, as well as translations of writings by Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin. He and two associates, John Queen (who would later become mayor of Winnipeg) and Charles Manning, organized and conducted a “socialist Sunday school.” They wanted to teach alternatives to conventional capitalist political models to the children of the working class, dominated by immigrants. Being fluent in Russian, German, and English would have made Penner well suited for these roles, though his linguistic capabilities and accented English also raised suspicion among his political foes.

In Canada during these years, Penner was open and completely transparent about his political leanings and activities. But his German background, anti-war tendencies,39 and opposition to conscription during the First World War were disliked by customers at the flower shop where he worked, and his views eventually led to his dismissal in 1918.40 Such anti-German sentiments, as well as harsh opposition to his outspoken political ideology, would follow him throughout his political career.

He soon found brief employment as a clerk at the Eaton’s department store in downtown Winnipeg, where he quickly became involved in the newly formed clerks’ union.41 Again, his political activity soon put an end to this job. He then became a salesman at the L. Galpern Candy Company, owned by Rose’s brother-in-law. “A person more ill-suited to a job you could never find,” said his son Roland.42 With a generous heart and fondness for children, he became known in the neighbourhood as the “candy man.” By the time he had walked the two blocks to Main Street to catch the streetcar and begin his daily rounds, half the candy from his large sample case would be given away.43 In the 1920s, Penner became a member of the Bakery and Confectionery Workers’ Union. According to Roland, he was never a union executive or organizer, but concentrated on action in the political realm.44

Penner supported activities that led to the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, but he could not be officially named as a member of the strike committee. Organizers feared that his perceived German-Russian background would only confirm their opponents’ claim that the strike was a Bolshevist conspiracy, and that this would be used to destabilize the movement in a public relations war.45 When the leaders of the Winnipeg General Strike were arrested and the strike crushed in June 1919, Penner became active in the Defense Committee, which raised money to defend the leaders of the strike against charges of seditious conspiracy.

During the Winnipeg General Strike, Penner was likely following news of the civil war back in Russia that had been precipitated by the revolutions of 1917.46 Penner did not consider the General Strike a move toward revolution. “It was purely a trade union strike,” he said, with the main aim of having “the principle of collective bargaining recognized.”47 In the years that followed Penner would commit himself to the communist movement. At a secret meeting in Guelph, Ontario, in 1921, the Communist Party of Canada was founded. Penner was named Western Organizer. However, the party decided not to publicly announce its formation out of fear that Section 98 of the Criminal Code, enacted to crush the Winnipeg General Strike, might be employed to indict the leadership of the new party. It operated under the name of the Workers’ Party of Canada, which included communists and non-communists, until in 1924, when it openly became the Communist Party of Canada, affiliated with the international Communist movement.48

Politically, these years must have been a blur for Penner. He was roundly defeated in a 1921 run for federal office, and again in 1927 for provincial office, before eventually being elected as a Communist candidate to Winnipeg’s city council. In the next issue of Preservings I will continue to explore the political career of Jacob P. Penner.

Dan Dyck is a self-directed student of history. He is distantly related to Jacob Penner through both his parents’ lineages. This was discovered midway through the research for this project.

- Special thanks to Kathy Penner, Cathy Gulkin, Lori Penner, Wendy and Ron Dueck, Conrad Stoesz, Mennonite Heritage Archives, Chris Kotecki, and Manitoba Provincial Archives, for their assistance and freely sharing of resources. Thank you to first readers Conrad Stoesz and Randy Penner, who made excellent suggestions for improvements. Any errors are my own. ↩︎

- Delbert Plett, “Penners of Friedensfeld, Russia: Part Two,” Preservings, no. 9, part 1 (1996): 26. ↩︎

- Plett, “Penners of Friedensfeld, Russia: Part Two,” 28. ↩︎

- Johann W. Dueck, “The Johann Dueck (1801–1866) Family,” in History and Events, ed. and trans. Delbert F. Plett (Steinbach: D. F. Plett Farms,1982), 87. ↩︎

- J. Dueck, “Johann Dueck Family,” 86. ↩︎

- Wendy Dueck, “The Penners of Friedensfeld, Russia: Part One” Preservings, no. 8, part 2 (1996): 34. ↩︎

- Wendy and Ron Dueck, telephone interview, Nov. 20, 2020, quoted with permission. ↩︎

- Profile # 707378, GRanDMA (The Genealogical Registry and Database of Mennonite Ancestry) database, v6.2.49 (California Mennonite Historical Society). ↩︎

- Wendy and Ron Dueck, interview. Ron recalls reading that Peter D. Penner’s family looked down on him for the way he had used family estate money that siblings felt belonged to them. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, A Glowing Dream: A Memoir (Winnipeg: J. Gordon Shillingford Publishing, 2007), 16. ↩︎

- Wendy and Ron Dueck, interview. ↩︎

- Wikipedia, s.v. “History of Riga,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Riga. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 16. ↩︎

- Cathy Gulkin, email correspondence, Aug. 20, 2019. ↩︎

- Jacob Penner, television interview, Eye to Eye, CBC Manitoba, 1962, Cathy Gulkin collection. For more of Jacob Penner’s own words, see Jacob Penner, “Recollections of the Early Socialist Movement in Winnipeg,” Histoire Sociale/Social History 7, no. 14 (1974): 366–378. ↩︎

- Wendy and Ron Dueck, interview. ↩︎

- The first Mennonite church in Winnipeg was the Winnipeg City Mission, which began in 1907. In 1913 it was officially organized as a congregation, as the North End Mennonite Brethren Church. ↩︎

- Wendy and Ron Dueck, interview. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, video interview, 2000, Cathy Gulkin collection. ↩︎

- Victor G. Doerksen, trans. and introduction, “A Letter from Winnipeg in 1907,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 15 (1997): 191–196. Jacob apparently worked for a time in the fruit orchards of British Columbia upon his arrival in Canada, though precise dates are not clear. In the letter to his uncle he writes glowingly of conditions and opportunities in that province. This episode of his life is not noted in son Roland Penner’s memoirs, although this letter is reprinted there. One can speculate that the presence of family drew him back to Manitoba. ↩︎

- John Dyck, comp., “Manitoba Mennonites Attending Post-Secondary Schools, 1890–1924: Brief Biographical Sketches,” ed. Adolf Ens, Preservings, no. 27 (2007): 68. ↩︎

- Gerhard J. Ens, “Die Schule muss seine”: A History of the Mennonite Collegiate Institute (Gretna, MB: Mennonite Collegiate Institute, 1990), 50. ↩︎

- Ens, History of the Mennonite Collegiate Institute, 51. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, A Glowing Dream, 17–18. Rose’s story is worthy of its own research and study. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 17. ↩︎

- Ruth Penner, video interview by Cathy Gulkin, 2000, Cathy Gulkin collection. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 17; see also Ruth Penner, interview. ↩︎

- Jim Blanchard, Winnipeg 1912 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2005), 189–212. ↩︎

- Stefan Epp-Koop, We’re Going To Run This City: Winnipeg’s Political Left After the General Strike (University of Manitoba Press, Winnipeg, 2015), 11. ↩︎

- Blanchard, 209. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, interview. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 25. ↩︎

- Jacob Penner’s GRanDMA profile (#789820) shows two infants, one unnamed, and one named Norma, who did not survive childhood. Manitoba Vital Statistics lists only one of these infants, a child named Leonora. Surviving family members Wendy and Ron Dueck speculate that Norma and Leonora are the same child. There is no family memory of the unnamed child in the GRanDMA database. ↩︎

- Ruth and Roland Penner, video interview by Cathy Gulkin, background for A Scattering of Seeds, White Pine Pictures, episode 33, 2000, Cathy Gulkin collection. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- City Bread is a North End Winnipeg kosher bakery that produces a light rye bread said to be unique to Winnipeg. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 244n22. ↩︎

- Ens, History of the Mennonite Collegiate Institute, 51. ↩︎

- Although son Roland and other sources describe Jacob Penner as a pacifist, he himself in a video interview said, “I was not a pacifist . . . but I disagreed with World War I. I regarded it as a trade dispute between Great Britain and Germany. I considered that Canada had no interest in this dispute.” J. Penner, interview. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, interview. ↩︎

- Penner was one of the originating members of the Retail Clerks’ International Union and was still a member at the time of the Winnipeg General Strike. Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 159. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, interview. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 27. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 159. This claim is contradicted by another source that claims Penner was General Executive Secretary of the Food Workers’ Industrial Union, headquartered in Winnipeg. – John Hanley Grover, “Winnipeg Meat Packing Workers’ Path to Union Recognition and Collective Bargaining,” (Master’s thesis, University of Winnipeg, 1996), 52–53. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 24. ↩︎

- We know Penner had some direct access to news from Russia. A report by an undercover agent to the Royal Northwest Mounted Police dated July 3, 1919, says Penner admitted having in his possession two anti-Bolshevik newspapers, brought back to Winnipeg by his brother after a visit to Siberia. Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, appendix 3. ↩︎

- J. Penner, interview. ↩︎

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 26. ↩︎