Returning Home: Martin B. Fast in Molotschna Colony

Katherine Peters Yamada

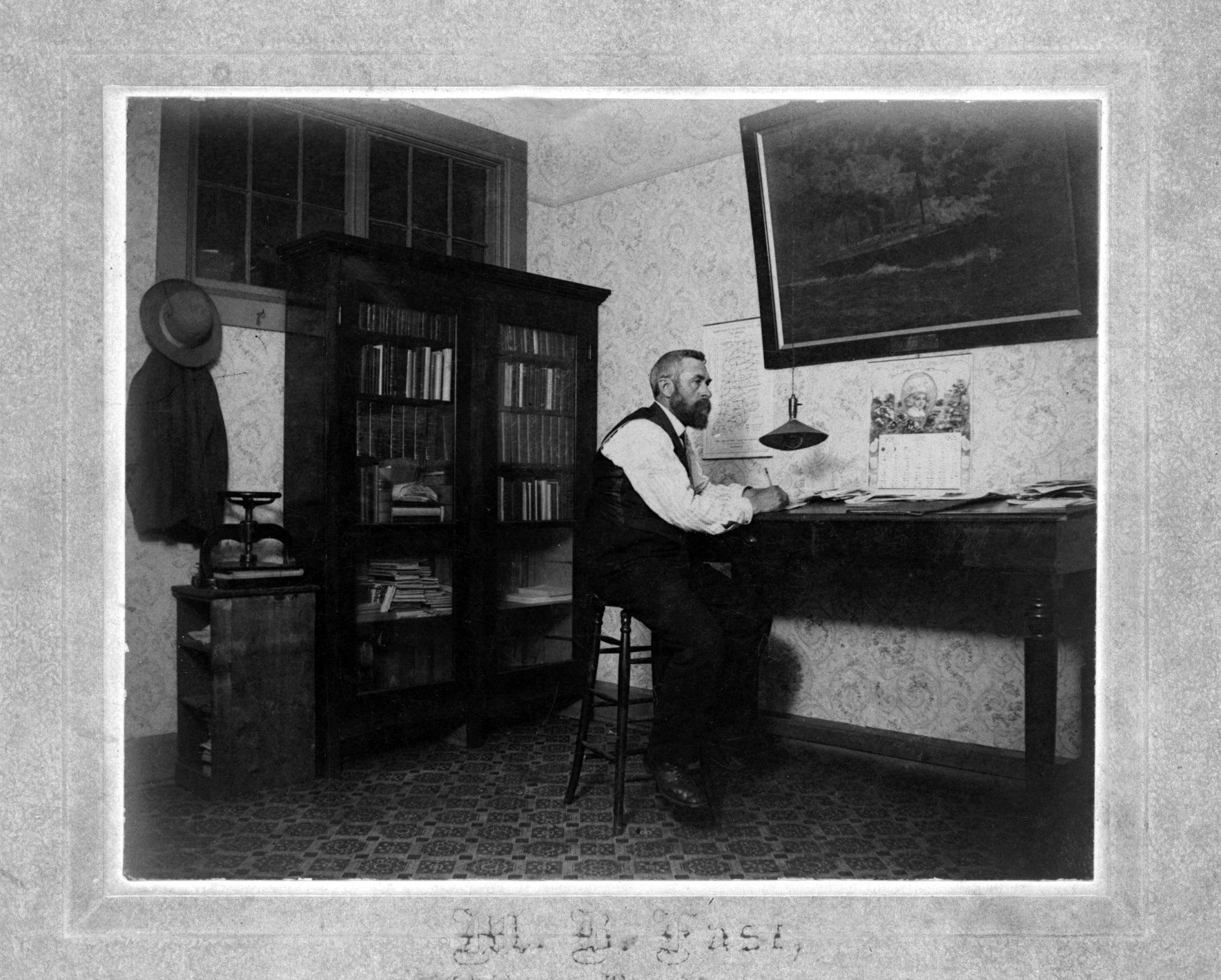

In the opening pages of his book Reisebericht und Kurze Geschichte der Mennoniten (A travelogue and brief history of the Mennonites), Martin B. Fast wrote that he had long wished to make a trip back to his homeland in South Russia.1 This wasn’t such an unusual idea. Many people who had left the colonies in the 1870s returned to visit those who had remained. Fast, who was the editor of Die Mennonitische Rundschau, distributed in North America, Europe, and Russia, hoped to contact not only friends and relatives, but also church and community leaders he had become acquainted with through his work.

Sailing from New York in May 1908, he disembarked in Bremerhaven and boarded a train for Hamburg, where he visited Hinrich van der Smissen, the pastor of the Hamburg-Altona Mennonite Church. Van der Smissen was also editor of the Mennonitische Blätter, which had the distinction of being the oldest periodical of German Mennonites.

As the two men walked to the church, Fast observed that the parsonage and the church buildings, both built of brick, were already quite old. In the library, van der Smissen showed him many old and valuable volumes and a letter written in Menno Simon’s own hand. Fast was allowed to take two small books home and wrote that he planned to publish an excerpt in the Rundschau. Although the church’s membership was quite large, Fast learned that many members lived some distance away and only a few attended services. When he returned the next day to celebrate Ascension Day, he wasn’t surprised to see just eighteen worshippers in the large sanctuary.

From Berlin

The next morning, Fast left for Berlin. He informed his readers that “Berlin’s streets are beautifully clean and the imperial castles, the government buildings, and the residences of the wealthy are all more or less practical and massively built.” After seeing the sights from a tour bus, he made his way to the large station on Friedrich Street and waited for the train to Warsaw, which would take him into the Russian empire.

Warsaw’s station was crowded and busy. Fast quickly realized that he did not know which train went to Molotschna, and help was not forthcoming. Fast observed: “No one knew anything about Halbstadt.” Luckily he recalled the German village of Prischib, on the outskirts of the Molotschna colony.

He was able to purchase a third-class ticket that took him as far as Kiev. In that historic city, he visited several churches and observed the rites of the Greek Catholics. “I saw much there that I found very interesting,” he wrote. Fast showed curiosity about the religious culture of the city, commenting: “For centuries Kiev has been the holy seat (of the Orthodox church) and even today it is the centre to which every Russian makes a pilgrimage if at all possible. Huge sums were collected in Russia in order to build the great churches. The golden cupolas shine and gleam in the sunshine.”

He left Kiev on the evening train. At the next stop, Fast spoke to two young German-speaking men who were just boarding. They advised him to take the train to Aleksandrovsk and then hire a carriage to Schoenwiese, an industrial centre on the edge of town. There he could rest before continuing to Prischib.

In Schoenwiese, Fast received a friendly welcome from the village elder named Siemens, who invited him to spend the night. His wife told Fast about a violent pogrom against the Jewish population that took place in 1905. Fast informed his readers that Frau Siemens had witnessed unrest among the population and “a number of Jews [had] fled to her place. She took the women and children under her wing.” During this pogrom, local inhabitants destroyed Jewish businesses and left more than thirty Jews dead.

The next morning, Fast was awakened at three o’clock and driven back to Aleksandrovsk, where he boarded the southbound train. “When I finally found a seat, the sleeping passenger sitting across from me seemed familiar. And sure enough, quite unexpectedly I was among brethren. Brothers Suckau and Abr. Isaak I still remembered, although I couldn’t recall their names immediately. There were more brothers on the train; they had just come from Kotlyarevka, where they had participated in a conference of the Mennonite Brethren and were returning now to Rueckenau.”

To Molotschna

Fast and his new companions departed the train at Prischib station, which was some distance from town. When he saw the onrush of the carriage drivers, he was “glad that [he] had not come alone or in the evening.” They engaged a carriage and headed for Prischib, just outside the Molotschna colony. Now their travelling party included Brother Braun of Neu-Halbstadt and his elderly mother, who had just returned from the far north. The road to Prischib was very poor. Fast learned from his companions that this was normal: “Brother Suckau said that the road is always bad – a lot of dust in the summer and in winter all mud. We swallowed as little dust as possible, but it was really very unpleasant.”

They came to the Molochnaia River. The bridge and the embankment were high, but Fast reported there was no water in the riverbed. For Fast, crossing the bridge had symbolic meaning: “We passed over the bridge and found ourselves in Mennonite territory.” He noted that the tall poplars, “which used to stand so splendidly and offered cool shade to the passersby,” were withering away. As they drove through Halbstadt, Fast looked for changes made after he left in 1877. He noted that everything seemed familiar, except the addition of a large steam-driven mill.

When they crossed the “Wolfslegt,” which was just as “deep and crooked” as it had been when he was young, Fast knew they were close to his birthplace, Tiegerweide. His fellow travellers gave the Russian driver instructions to enter the yard of Fast’s uncle, Bernhard Fast. On the yard, no one recognized him. After he identified himself, Fast’s aunt responded, “Well, now, I’ll first go get a picture.” He then passed on greetings from his family, cleaned the dust off his clothes, and had coffee. Later, they walked outside to look at the yard where he had played as a child.

Fast recalled that “Tiegerweide used to be off the beaten path.” In his day, the school building was small and unattractive – the teachers changed frequently. “In six years, I had five different teachers. And they were not allowed to change the pronunciation of the old Low German alphabet. How much has changed! Now a massive school building stands along the street and the equipment and furnishings – everything is modern.”

To Rueckenau

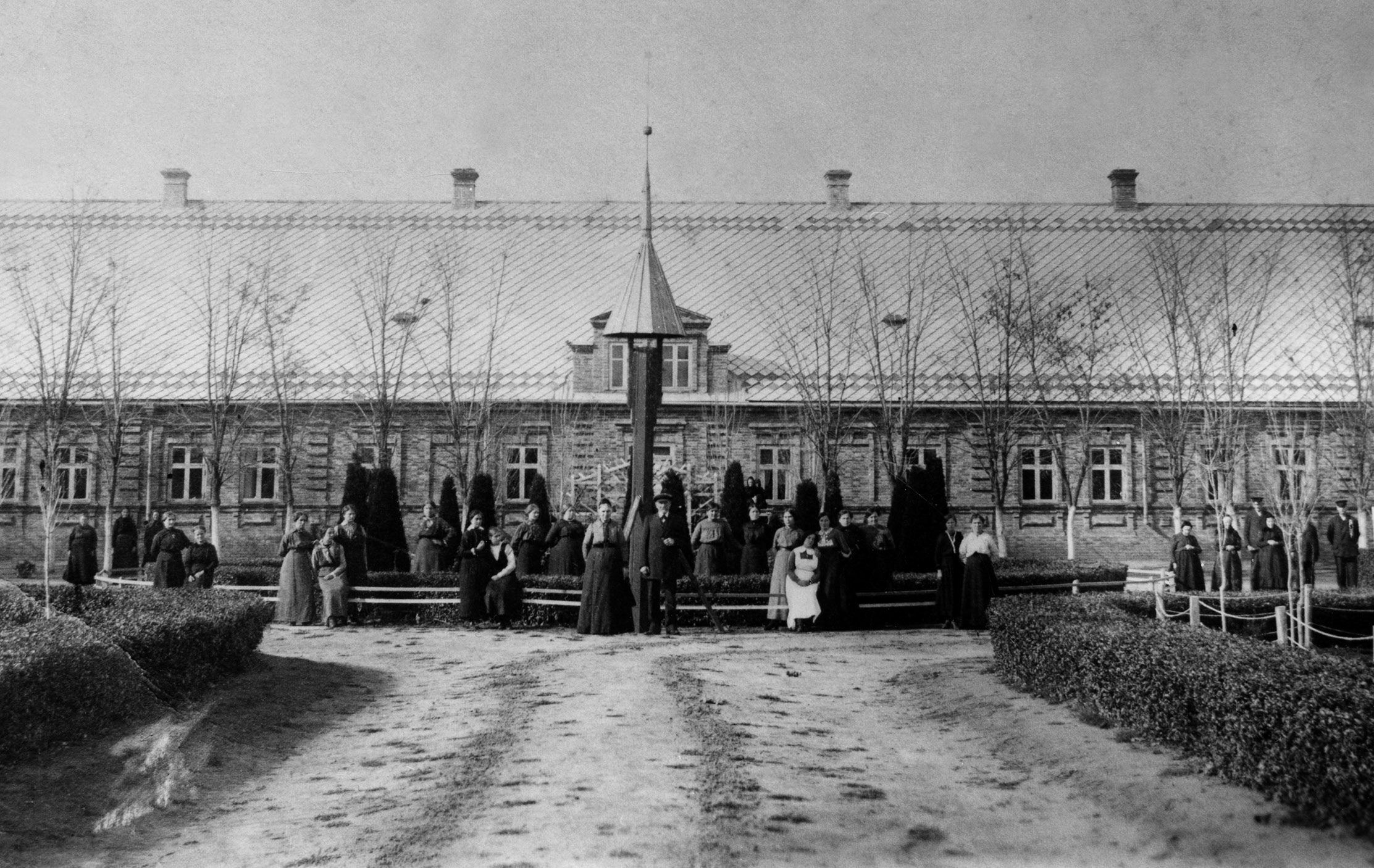

They arrived in Tiegerweide the day before Ascension Day. Fast had already celebrated this holiday in Germany at the Hamburg-Altona Mennonite Church, which used the Gregorian calendar. But Russia was still on the Julian calendar, and therefore thirteen days behind western European countries. The next morning, Fast and two of his cousins drove to Rueckenau for the meeting. “The road to Rueckenau was still the same as it had been years before,” he noted. This was the village where his mother, Aganetha Barkman, had been born and raised. In 1904, just four years before Fast’s visit, a huge fire had broken out and destroyed the buildings in at least thirty-five farmyards.2

While the road was the same, the fire had changed the village. As Fast remarked, “There lay the village before me; completely different from how I had left it thirty-one years ago. The tin roofs and the beautifully painted gables, etc., show from a distance that everything is new.” They drove down into the village and saw that a few of the old fences were still standing; however, little else remained from the former town. Fast sought landmarks, “but everything looked strange.” He eventually recognized the Mennonite Brethren (MB) church at the northern edge of the village.

At the door of the church they met Brother Wilhelm Loewen, from Alexanderkrone, who invited Fast to sit in front of the pulpit and speak to the congregation. This was a new experience for Fast. He had grown up in the Mennonite church in Neukirch, and had not been permitted to attend services in the Mennonite Brethren meetinghouse in Rueckenau. “I saw many brothers and sisters at the meeting, grey-haired and in some cases even white. In those former days you wouldn’t have believed that you would ever meet them, or even see yourself, in an MB church.” Afterwards, he greeted many old friends, commenting, “It is remarkable how you get carried away with emotions in such circumstances.”

Fast spent the night with Brother and Sister Gerhard Martens. “Brother Gerhard is – I really am not sure what title to give him – maybe a sort of archdeacon.” Fast listened in astonishment as Martens recounted all his activities. He was impressed: “The MB churches in the Molotschna [colony] have already built and maintain a number of meeting houses. I think we in America can learn something from this.”

In the afternoon he walked with his friends to the home where his Barkman grandparents had lived. His grandfather, Martin Barkman, who was born in 1796 in Prussia, left for Russia in 1818 with his older brother to avoid military conscription. Travelling by night, they hid under grain stocks by day. Martin married Katharina Epp Regier in 1819 and they acquired a farm (Wirtschaft) in Rueckenau. It included a brick hay shed, which only the more established farmers could afford. He served as mayor of the village for a time. Martin and Katharina had nine healthy children; they all grew to adulthood, married, and had their own families. Their seventh child, Aganetha, married Peter Fast and gave birth to Martin B. Fast in 1857.

To Neukirch

Fast later attended a service in his boyhood church at Neukirch. This church was organized in 1863, when Fast was about six years old, as an offshoot of the Ohrloff Mennonite Church, the oldest congregation in Molotschna. The Neukirch church building was erected two years after the congregation was founded. In 1905, the church had 402 registered members.3

As Fast drove into the churchyard, he saw the sand-strewn walkway, and thought back to the time when, as a young boy, he was “so proud that this was my church too.” He had only been in the Ohm-Stübchen (anteroom) a few moments when Brother Gerhard Epp and “dear ‘Uncle’ Abraham Goerz, the church elder,” entered. Goerz had ministered to his family before they had departed from Russia. Fast was overcome with emotion: “My heart was so full.” As he entered the church, he saw a large assembly with young people seated in front, “because after all it was the Sunday before Pentecost!”

After the service, they drove to Alexanderkrone to visit family. The main streets of the two villages were connected by a bridge over the Iushanlee (Juschanlee) River, and Fast saw many vehicles driving over. Learning that there was a baptism in Lichtfelde, he expressed a wish to attend. He discovered that the baptismal candidates were from Rueckenau. Fast commented, “The people who had been tested about their faith in Rueckenau on Thursday [Ascension Day] were now being baptized here. In Rueckenau the water was too shallow but there was still a lot [of water] in the Juschanlee near Lichtfelde.”

They also visited a Mennonite Brethren home for the elderly in Rueckenau started by the minister and historian P. M. Friesen. As Fast observed, “The widows and the old men all seemed to be happy. The furnishings are very simple. Thank God that among our people there are now a number of lovely homes in which the elderly who have no home can lead a carefree life.”

To Tiege

During the evening, Fast heard about the Maria School for the Deaf in Tiege. He asked his friend Jakob Neuman to drive him early the next morning to meet the children and their teachers before they left for the school break. On their way west to Tiege, they passed another home for the elderly, Kuruschan Altenheim. At the time there were forty-nine residents, including “twelve married couples, nineteen widows, three unmarried women, and three fallen women.”

The grounds of the home included a cemetery. Fast shared with his readers that the director, David Epp, had asked the residents to select a plot where they would be buried. As Fast explained: “[Epp] didn’t set it as a condition but he did say he would like to fill one quarter [of the cemetery] first. The next morning they each brought their copy of the plot plan and on it their designated spot. But no one had chosen the quarter that was to be filled first!”

Fast and Neuman continued southwest, following the road along the Kuroshany (Kuruschan) River. He saw several farms that reminded him of the United States. Fast noted: “It looks just as if you were driving down a section road in Nebraska or Kansas. To be sure, the building style is still that of our fathers but there are a few deviations from the old style. You see large, beautiful gardens and plantings; also a large factory where metal roof panels are made, located near the old large sheep farm.”

After a long drive, they finally arrived in Rosenort. The rows of houses looked the same as when his grandparents lived there. His grandfather, Bernhard Fast, had been the schoolmaster for thirty-eight years in both Rosenort and Johannesruh. His grandmother, Justina Isaak, was a sister of historian Franz Isaak.

Blumenort was not far away and Tiege, the next village over, was their destination. Tiege, one of the earliest villages of the Molotschna colony, was established in 1805 on the south bank of the Kuroshany River. The location reminded one settler of the Tiege River that flowed through his home village in Prussia and he had requested the name. In addition to the Maria School for the Deaf, the village boasted a girls’ school and a doctor’s office.4

Fast was impressed by the school for the deaf. He commented that the building was “beautiful and built massively.” He was introduced to teachers Unruh and Janzen, who took time from their busy schedules to present the students to him. The school, named after Tsar Alexander II’s wife Maria, offered a nine-year elementary education, along with training in woodworking, sewing, basket weaving, and other skills. An annual sale of crafts raised funds for the school. Considered one of the finest schools of its kind in Russia for its low student-teacher ratio, it had well-trained teachers who were properly paid.5

They drove on as far as Ohrloff, which had 510 residents and numerous businesses, several schools, a church, and a hospital, before returning to Tiegerweide for night.6

To Margenau

After more visits, Fast packed a satchel and left Tiegerweide with his friend G. Plett, who drove him to his cousin Jul. Barkman’s home. Barkman lived in Alexanderwohl, founded in 1821 by a Flemish congregation from West Prussia. The village received its name after a chance meeting with Tsar Alexander I as the congregation migrated to the Molotschna colony. The tsar wished them well (wohl) in their journey and they named their village in memory of this event. The entire village left for Kansas in 1874 and other Molotschna colony residents moved into Alexanderwohl after their departure.7

Fast left Alexanderwohl early in the morning for Margenau. Minister Jakob Thiessen of Neukirch drove him there to attend a Pentecost service and an ordination. Fast wrote: “Peter Friesen, the son of Jakob F. Friesen of Tiegerweide, was for some years the elder of the Margenau congregation. He had died about a year previously and the congregation had elected Plett from Hierschau as elder. He was willing to take over the responsibilities of an elder but only under certain conditions; one of the conditions was that he be allowed to introduce foot washing, something the majority of the congregation was against. In the end, however, the congregation gave in and the ordination date was set.”

By the time Fast and Thiessen arrived, the small, old church was already filled. “We went into the ‘Ohm-Stübchen’ and were astonished to meet a large number of preachers, deacons, and bishops there. It was suggested and then agreed to that the ‘American’ would open the service. I am not ordinarily so shy but facing this large assemblage I felt a bit weak. The church could not contain all the guests. All three floors and the corridors were crowded.”

After Fast spoke, Koop, the elder of the congregation in Alexanderkrone, gave an address appropriate to the occasion. After Plett had answered the usual questions, he was ordained and blessed by Koop. As Fast recalled, “All the preachers and elders were given the opportunity to welcome him. The goodwill wishes and blessings were of varying lengths, some short, some long, some poetical, others in prose.”

Plett then gave a “serious and all-encompassing address. Among other things, he said that he has taken up the work not as a kirchlich, nor as a Baptist, nor as a separatist – but rather as an evangelical. We were pleased at the courage that he showed in saying this.” After the service, Fast returned with Thiessen to Alexanderwohl, where they enjoyed the usual holiday meal.

In the morning, the second day of Pentecost, they drove back to Rueckenau for a service. Fast described the religious atmosphere of the meeting: “We were happily surprised to hear so many brothers and sisters pray. The missionary Abr. Friesen preached to the children.” His friends, the Gerhard Dicks of Alexanderkrone, and their children were there, just back from Siberia, and he lunched at their table in the church dining room. There, he met many friends. In the afternoon, holy communion was observed.

To Steinbach

After the meeting, he left Rueckenau with Brother and Sister Gerhard Enns and travelled to Steinfeld. Fast wanted to make his way to Gnadenfeld for a mission festival. Toward evening, Enns drove Fast to Steinbach; he would be able to continue to Gnadenfeld in the morning. This was Fast’s first visit to a Mennonite-owned estate. Most Mennonites had settled in villages, but others rented land for large farming operations. Steinbach, established by Klaas Klaas Wiens, was considered the first estate owned by a Mennonite. Wiens and his wife, Anna, had arrived in South Russia in 1803 and he was delegated to plan, organize, and lay out what became the Molotschna colony.8 In 1812, Wiens leased a large estate from the Russian state. It was along the Iuschanlee River at the southern edge of the colony, between Steinfeld and Elisabethal. Wiens covered much of the land with new trees. Six years later, Tsar Alexander I was so impressed on his visit to the estate that he granted Wiens a large landholding.

The couple had four children, including a daughter who married Peter Schmidt. When Wiens died in 1820, ownership of the estate was transferred to Schmidt. It was still in the Schmidt family when Fast visited in 1908. By then the estate was one of the largest Mennonite land holdings in southern Russia.9 Fast went there to bring greetings from his former neighbour Peter Jansen to Jakob Dick, who had also married into the Schmidt family. “The buildings and surroundings in Steinbach are really extraordinary,” Fast wrote.

Fast found most of the family gathered at Peter Schmidt’s house, on the south side of the road that he had often taken with his father as they travelled to Berdiansk before their departure to the United States in 1877. He was heartily welcomed and had a pleasant conversation with the brothers Nikolai and Peter Schmidt. Eventually the men spoke about politics. Schmidt related how, during a recent uprising in the Crimea, “thousands of sheep were driven away [and] much grain was taken out of their warehouses.” Although Fast did not provide context for this conversation, it seems to have been connected to the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Fast had been invited to join them for dinner. He wrote: “Brother Schmidt’s dining room is very large and soon we were ordered to the richly set table. After dinner they gathered around the family altar with the family and the domestic servants. We read God’s Word, commented on the reading and then prayed.”

To Gnadenfeld

A carriage was waiting for them early the next morning. On his way out of the estate, Fast saw Steinbach’s herds of cattle and its beautiful fields. There was a direct road from Steinbach north to Gnadenfeld. By 1835, Tsar Nicholas I had restricted immigration, but a congregation of Flemish Mennonites from Prussia appealed to him for permission to move. They named their new village for the mercy (Gnade) shown by the tsar and for its location in a field (feld) on a slight hill. In 1854, they built a large church, which could accommodate five hundred people. They held child blessings, organized Bible study groups and mission festivals, instituted foot washing, and emphasized temperance.10

Fast entered the Ohm-Stübchen, where he saw Elder Abraham Goerz, Elder H. Unruh, Minister Gerhard Harder, son of the well-known preacher and poet Bernhard Harder, and others. During the service, Elder Dirks gave a short report and the pastor from Stuttgart gave the opening. After Fast spoke, the choir sang a “beautiful missionary hymn with organ accompaniment.” Then Elder Dirks gave a “wonderful sermon” and the meeting was closed. Dirks invited them to his house and “although it was the final day of the Pentecost holiday, there was enough Plumemoos and ham to satisfy everyone.”

In the afternoon there was another service. First Brother Unruh preached, then Brother Harder. Unruh had visited the United States but not Nebraska, where Fast lived. Fast was impressed with Unruh’s words: “Since the time when the discord took place in the Ohrloff church, I had had the impression that Brother Unruh was quite aristocratic in his manner – but I can say that on my trip I did not get to know anyone with whose writing I was familiar or whose name was known to me in whom I was so very much mistaken. In his public appearance and in his speech he is uncomplicated and loving, so that everyone can understand him.” Fast also showed interest in the religious changes taking place among Mennonites: “In the old days the mission festival was conducted only in the church in Gnadenfeld. But all that has changed in Russia – mission festivals are now conducted in all the Mennonite churches. That is a step in the right direction.”

In the next issue of Preservings, Martin Fast’s trip will continue to the Crimean Peninsula.

Katherine Peters Yamada is a journalism graduate of Fresno State College in Fresno, California. She has written numerous family histories and has searched for her roots in Holland, Prussia, and Russia. Martin B. Fast was her great-uncle.

- Martin B. Fast’s Reisebericht und kurze Geschichte der Mennoniten (Scottdale, PA, 1909), was translated in 2017 by George Reimer. Reimer, who grew up in a German-speaking household and did the translation for the love of reading his first language, died unexpectedly in late 2019. ↩︎

- Rudy P. Friesen, Building on the Past: Mennonite Architecture, Landscape and Settlements in Russia/Ukraine (Winnipeg: Raduga Publications, 2004), 352. ↩︎

- Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO), s.v. “Neukirch Mennonite Church (Molotschna Mennonite Settlement, Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine),” by Cornelius Krahn. ↩︎

- Friesen, Building on the Past, 370. ↩︎

- Ibid., 373. ↩︎

- Ibid., 338. ↩︎

- Ibid., 247. ↩︎

- GAMEO, s.v. “Wiens, Klaas Klaas (1768–1820),” by Susan Huebert. ↩︎

- Friesen, Building on the Past, 629. ↩︎

- Ibid., 269. ↩︎