The Mennonite Problem: Public Schools in Saskatchewan

Leonard Doell

As early as 1902, the Old Colony Mennonites in the Hague-Osler area, north of Saskatoon, were confronted with the issue of public schools. They had only arrived in Saskatchewan a few years earlier (the Hague-Osler Reserve started in 1895) and were now threatened with the closure of their private schools. The earliest school districts to be formed were in the Hague area. To increase its tax base, the Hague School District wanted to have a large catchment area that included four nearby Old Colony Mennonite villages. The residents of the villages sent petitions to the Department of Education stating their concerns and their opposition to these public schools, since they had their own schools and did not want to support another one. They were told by Mr. J. A. Calder, deputy commissioner of education, “that even if they had their own private schools, it would not relieve them from the liability to taxation in the Hague School District.”1

Calder then suggested a solution to this problem, stating that “as [the] Mennonites to whom you refer are opposed to public schools, it would be advisable if at all possible to so arrange the boundaries of the district that when the vote is taken, a majority would be in favor of it.”2 His advice was followed in these areas: the school district carefully cut its boundaries leaving out the Old Colony villages.

To build a public school, school districts needed to purchase land. They had trouble doing so in the Hague-Osler Reserve as all of the land was owned by Mennonites. In places where they managed to find land, some of the sellers claimed they were coerced. For instance, in the village of Hochfeld, a Mr. Bartsch sold his land where the publicly funded Passchendaele School was built. However, he wrote: “I have sold this land under threat from the school inspector and the official trustee of the above named school district. They threatened to prosecute me if I refused to sell this site.”3

Teacherages also had to be constructed immediately in these districts because there was no housing that could be acquired for teachers in the village. The Department of Education found it almost impossible to get a teacher in the Old Colony Mennonite villages if there was no house for them to live in.

In 1919, the provincial government built four schools in the heart of the Mennonite reserve against the wishes of the Old Colony Mennonites. There was Venice School at Blumenthal, Renfrew at Blumenheim, Passchendaele at Hochfeld, and Pembroke in Neuanlage. The government also named the schools after First World War battle sites. The names were intentionally chosen to aggravate the Mennonites because of their pacifist beliefs and their resistance to public schools.

The government also hired several teachers, including some with a Mennonite background who were not opposed to public schools. Some were from accommodating Mennonite groups while others were former Mennonites who spoke Low German but were now Seventh Day Adventists, or Swedenborgians. They also chose official trustees who reported if the children attended school and generally kept the government informed as to the development of these schools. Some of these men were also of Mennonite background. Old Colony Mennonites were often frustrated with these trustees and their insensitivity and lack of compassion as they carried out their responsibilities to the letter of the law.

The biggest challenge that the government encountered was attendance. As early as 1915, the provincial government began to prosecute Mennonites for not sending their children to public schools. Canada was at war and there were very strong feelings in support of everything British and against everything German, especially Germans who did not serve in the military. There was no alternative service at this time, which also “contributed to the strong feelings against Mennonites. The unwillingness of Old Colony Mennonites to accept public schools was just one more factor.”4 Bill Janzen describes how the government intensified the push toward public schools: “In this war-time atmosphere the provincial government, in the spring of 1917, passed the School Attendance Act. In effect this law made it compulsory for all children between the ages of 7 and 14 to attend a public school where English was the language of instruction, if the children lived within a public school district. The government now also had the power to create public school districts if the people living there did not want to do that on their own. Further, the government could expropriate land, have schools constructed, appoint official trustees who would then hire teachers, and impose fines and prison terms if children did not attend.”5

At first “the government . . . took enforcement actions mainly by fining people. It decided not to send parents to jail, lest they appear as martyrs. But it did not fine people in every village, only in some, counting, presumably, on a demonstration effect.”6 They chose rather to focus on the villages of Hochfeld, Neuanlage, Blumenthal, and Blumenheim initially, where many of the church leaders lived and church institutions were dominant. According to Janzen, the treatment of non-compliant Mennonites was harsh. He notes the following: “Eleven Mennonite districts paid a total of $26,000 in 1920–21 in fines and court costs. That was a lot of money in those years, enough to construct and furnish five one-room country school buildings with teacher’s residences.”7

The result of this relentless prosecution of Old Colony Mennonites through fines and prison sentences was extreme poverty. The intent of the government was to gain compliance by force, through starvation and poverty. Rev. Johann P. Wall, in a letter to the minister of education on February 12, 1923, wrote: “There are so many people who are weakened so much in a financial respect through the many, many prosecutions that it is a great loss to the country, especially to the District, since they have been unable to do their farming to the usual good methods. Yes, many of them could not support themselves any more and would be in need and misery if they had not been supported by others. But the credit is exhausted and paying the school fines will eventually cease. And when the farmers are deprived of their working stock they cannot do their farming. . . . Have mercy with our poor people. God will reward you for it. If you cannot keep the exemption that was granted to our people, please give us a few years to settle our affairs, we pray.”8

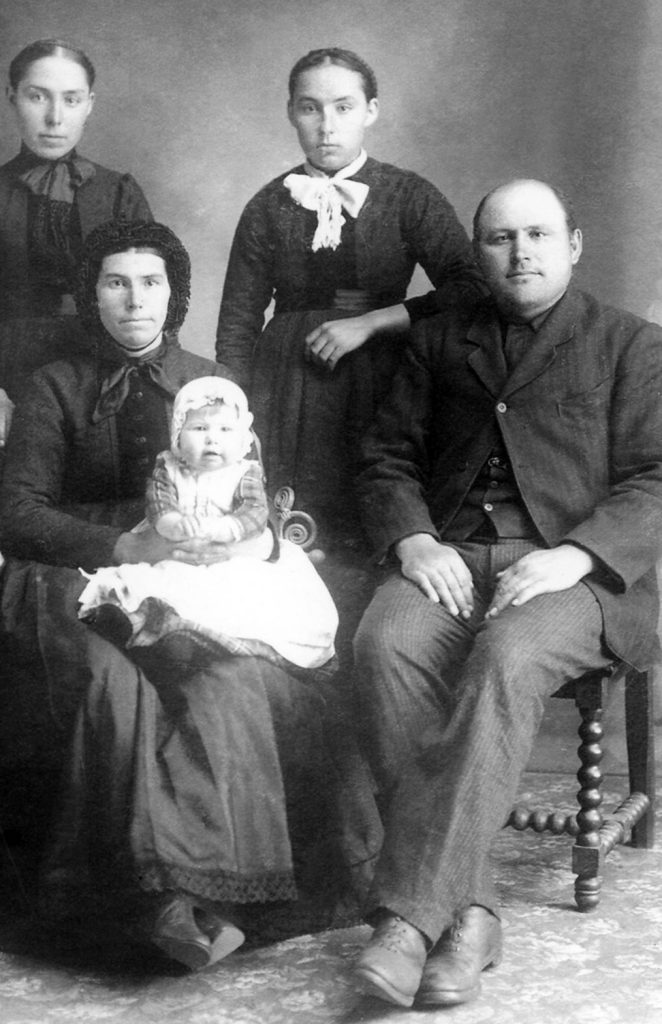

was part of the first group to arrive in Saskatchewan in 1895 and settle in

the village of Neuanlage. (PRIVATE COLLECTION)

Johann F. Peters of Neuanlage sent a letter to Saskatchewan Premier W. M. Martin that expressed the dilemma that the Old Colony Mennonites faced because they were opposed to the public schools and the continuous prosecution they experienced: “If we send our children to public schools, we violate God’s commands in not holding to that which we promised our God and Saviour at holy baptism. If we do not send them, we offend against your laws. Does Mr. Martin want us to transgress against God’s commands in order to keep his? . . . Oh how difficult it is to be a true Mennonite! . . . And we came here precisely because of the freedom which the government promised us in full.”9

The process of fining Mennonites started in 1915 and lasted until at least 1934. Mennonites were pursued by the local official trustees, attendance officers, justices of the peace, and the police. From 1917 to 1928, the Saskatchewan Provincial Police enforced the School Attendance Act. Later the Royal Canadian Mounted Police [RCMP] assumed this responsibility. The detachments at Vonda and Saskatoon were largely responsible for the Hague-Osler Reserve, including Aberdeen. Many Mennonites would argue that the police stridently carried out the letter of the law, but there are also a few stories of those who showed compassion and did not issue a fine. Mennonites from Manitoba and Swift Current left for Mexico as early as 1922, whereas the bulk of the Hague-Osler people began to move after 1924. The added years of heavy fines, jail sentences, and seizure of assets added to their poverty and strained relations between them and the authorities. According to the records of the Prince Albert Penitentiary, seventeen Old Colony men spent time in jail, sentenced to anywhere from ten to thirty days for being unable or refusing to send their children to public schools. Among those jailed were one Old Colony minister and three German school teachers.

In a September 1927 letter, inspector of schools A. J. Loeppky described the process used at Hague to deal with offenders: “Mr. A. H. Klassen, who is the official trustee for some of the districts, is also the Justice of the Peace. The system of punishment is very systematic. Mr. H. W. Fisher, who was formerly a Justice of the Peace, is attendance officer for School District #4116 and Mr. H. J. Friesen, the janitor of the Hague School, is the attendance officer for School Districts #4115 and #4117. At the end of each month, the summons are prepared and each attendance officer serves them. In many cases people do not want to appear in court and the attendance officer collects the fine when he serves the summons. The fine has been reduced as follows: the fine is $1.00, JP costs are $1.50 and serving the summons is $1.50. This brings the total up to $4.00. This amount is collected quite regularly. The number of convictions for June last year was 64. This brings a monthly income of $64.00 to the Government of Saskatchewan, $96.00 for Mr. A. H. Klassen and about $40.00 for Mr. H. J. Friesen and a smaller amount to Mr. H. W. Fisher and the other attendance officers. This has been carried on for many years, formerly the fine and court costs used to be higher and the people suffered severe hardships. Now the fine is a joke to those who can pay and the squatters of the villages are suffering. The people of the villages have become quite embittered against these men, who they say come every month in their big cars and take their last dollar and often their seed wheat and spend it to buy bigger cars.”10

The bishop of the Anglican Church of Saskatchewan, the Right Reverend George Exton Lloyd, in a letter to the premier of Saskatchewan, confirmed the words of Inspector Loeppky. He writes, “190 papers were issued by the same Constable from this Magistrate H. W. Fisher. I am told that over 150 were fined on that Saturday morning and as the cases were undefended, this unique representative of British justice is said to have pocketed over $400.00 for a piece of work between himself and the Constable. . . . In the meantime, this Justice is reported by Mennonites to have said that ‘he would prosecute them as long as Mennonites remain in the land.’ After your exposition of the school law, I do not hold the Attorney General responsible for the law but I do hold him responsible for the sort of men who are appointed to represent the King’s justice.”11

In 1928, a promise was made by the deputy minister of education to end the fines, but they continued even as Mennonites continued to pack up their belongings to move to Mexico. In July of 1932, the Department of Education threatened to remove children from homes and also to use the RCMP to force children to attend school, rather than using justices of the peace.

The perception in the Mennonite community was that the attendance officers and justices of the peace were not acting ethically, often charging more than legally required and pocketing the rest. They understood the fine should have been $4 per family per month and not $4 per child per month. This may or not have been true, but it is accurate to note that Mennonites were desperate as the government depleted their assets, while they could see the defenders of the law becoming wealthier.

Resistance

Mennonites showed resilience in the face of the steady onslaught of pressure and practiced various forms of civil disobedience. In 1921–22, official trustee J. J. Friesen said that some of the Hague area schools had to be closed because there were no students. Teachers were in schools without children, drawing their monthly salaries. In 1920, provincial school inspector J. E. Coombes visited Renfrew School and found that only one child out of forty-three in the community was in attendance. The father of the boy was almost blind and poor. The Old Colony ministers visited this man to see why he sent his child to school, and the man told them that he was too poor to pay the fine, and if the church paid it he would keep the boy at home.

In addition, when government officials came to Mennonite homes with children potentially of school age, the parents would refuse to give them their children’s names and ages. Likewise, when these same officials showed up at the private schools looking for similar information, the teachers refused to cooperate. I once met an older woman from our community who told me about an experience she had when she applied for Old Age Pension. She found out that she was actually two years older than she thought. It turned out that her parents had given officials a younger age to avoid paying fines.

There were also parents who sent their children to villages that did not have public schools to stay with relatives that were not being harassed. In some cases, the families moved out of their homes to other villages where they lived as squatters in tents, sheds, and summer kitchens. In other cases, they moved out of the three-mile radius that encompassed the school district and squatted on other people’s farmland. My great-grandfather had fifteen to twenty families squatting on his land just outside the Pembroke School District around 1920 to avoid paying fines. It was not long before new schools were built in these areas and Mennonites would move again, rather than send their children to school or pay fines.

There were Mennonite families assessed fines for not sending their children to school as late as 1933. In 1934, some of these families moved to Mexico, some moved to Peace River Country in northern Alberta, and some went to other remote parts of western Canada. Rev. Jacob B. Guenther, a Bergthaler minister from Aberdeen, continued to hold German school at his home near the Hague Ferry up until 1946. He attempted a move to British Honduras in 1951 that failed but in 1962 he moved to Bolivia with a small group of followers.

Conclusion

Many people who were in favour of public schools, including government officials and neighbours to Mennonites, became extremely frustrated and angry with the Old Colony Mennonites. They sought to find ways to compel them to comply with the law that would make them into desirable Canadian citizens. Throughout the correspondence on Mennonites and schools, the issue is referred to as “the Mennonite problem.” Our Mennonite people wanted to be respected as people with integrity who contributed to the betterment of life in Canada but in ways that did not conflict with their value system.

- Hague SD #759, Letter from J.A. Calder, Deputy Commissioner of Education Regina, SK, to Heinrich Harder (Reinfeld), Feb. 13, 1903, Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan (PAS). ↩︎

- Passchendaele SD #4084, Letter from Johan Bartsch, Hochfeld, SK, to Department of Education, Regina, June 7, 1919, PAS. ↩︎

- Altona SD #859, Letter from Deputy Commissioner of Education, Regina, to W. Wilson, Osler, SK, Sept. 11, 1902, PAS. ↩︎

- William Janzen, The 1920s Migration of Old Colony Mennonites from the Hague-Osler area to Mexico, Mennonite Historical Society of Saskatchewan Occasional Papers, no. 2006-1 (presented to the Annual General Meeting of the Mennonite Historical Society of Saskatchewan, Hague, SK, Mar. 3, 2006), 6. ↩︎

- Ibid., 7. ↩︎

- Ibid., 8. ↩︎

- Ibid., 9. ↩︎

- Ibid., 16. ↩︎

- Adolf Ens, Subjects or Citizens? The Mennonite Experience in Canada, 1870–1925 (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1994), 147. ↩︎

- Pembroke SD #4115, Letter from A. J. Loeppky, Inspector of Schools, to Deputy Minister of Education, Sept. 26, 1927, PAS. ↩︎

- Letter from the Right Rev. George Exton Lloyd, Anglican Bishop of Saskatchewan, to Premier Dunning, Premier of Saskatchewan, Dec. 28, 1922, PAS, M6-Y-101-4-1. ↩︎