A Hutterian Proposal

Dora Maendel

On a frosty, September morning in the Hutterian village of Hutterdorf in the Molotschna district of South Russia, Michael Mändel and his eldest son were milking their cows when Jacob first expressed his startling wish.

“I think I want to get married!”

“Mensch, why would you do that?”

“Tja – with Waldner David and Glanzer Paul married last Sunday, it’s time I started looking around too, no?”

“You are almost twenty.”

“That’s David’s age, and Paul is eighteen.”

“I was twenty when I married your mother; she was twenty-one. Who is your Hullerstaugen?”

“Oh, no one in particular …”

“Well, if you want my advice, go and talk to Kleinsasser Susie. On that acreage near Scheromet.”

“You mean the Jacob Gross widow?!”

“Die Sohn, jo!”

“Oh – maybe I should wait then.”

“There’s nothing to hinder you, not even the Johann Cornies rule, ‘No marriage before mastering a trade!’ You know farming as well as I do.”

“Let me wait some yet.”

* * *

The Mändels were Hutterites, whose Anabaptist forebears had fled to Moravia early in the sixteenth century to escape persecution. The Peasants’ War of 1524–25 had been unsuccessful in achieving any degree of improved living conditions for the peasants. The group followed Anabaptism’s two most important tenets: nonviolence and believer’s baptism.

In 1528, two hundred people left a group of Anabaptists who had been living in Nikolsburg to go to Austerlitz. On the journey they camped in a deserted village, where necessity inspired their leaders to spread a cloak on the ground and urge their people to lay their possessions on it to be shared by everyone according to need, in the pattern of the early apostolic church after Pentecost. Known as “community of goods,” this practice was quickly recognized as a brilliant survival technique and a valid form of expressing Christian love.

In 1529, Jacob Hutter, pastor of the Anabaptists in Tyrol, Austria, arrived in Moravia to investigate the possibility of bringing his congregants to Austerlitz to escape persecution. In 1533 he was elected to the position of Vorsteher (elder). In addition to escorting small groups to Moravia, Hutter provided strong, decisive leadership, which led to the group being given his name.

Hutterites were expelled from Moravia in 1622, after which they sojourned in Hungary and Transylvania, where continued persecution weakened the community. By 1690 they had abandoned community of goods. In October 1755 a group of Lutheran refugees from the province of Carinthia in Austria arrived in Transylvania near the beleaguered Hutterite settlement of Alvinz. The Austrian Lutherans attended Hutterian services and became inspired by the community of goods teaching, prompting the Hutterites to revive communal living, an event known in Hutterite history as the Carinthian Revival. The Lutheran family surnames of those who eventually joined the Hutterian group included Glanzer, Hofer, Kleinsasser, Waldner, and Wurtz.

In October 1767, sixty-seven Hutterites began the arduous trek over the Carpathian Mountains into Wallachia, Romania, where they succeeded in building communities and established a variety of trades. Less than a year later, however, war broke out between the Turks and the Russians. The Hutterian communities were raided by both Russian and Turkish soldiers. On April 10, 1770, the Hutterites migrated north into the Russian empire, arriving in present-day Ukraine on August 1 to settle on the estate of Count Peter Alexandrovich Rumiantsev. The village of Vishenka was established on the Desna River, northeast of Kiev, with supplies ordered by Rumiantsev.

In 1771, it was decided that Paul Glanzer should return to Wallachia and Transylvania to convince family members who had converted to other faiths to rejoin the community in Russia. From 1771–1795 seven such journeys were undertaken, some more fruitful than others, and fifty-six people chose to travel to Vishenka and become part of the community. En route through Transylvania and Hungary, Hutterite travellers also encountered Mennonite communities in Poland and Prussia. From these, fifteen families, with the names Decker, Entz, Gross, and Knels, joined the Hutterites and went to Vishenka. In Hungary, former Hutterites, named Mändel, Tschetter, Walter, and Wollman, were persuaded to join.

Upon the death of Count Rumiantsev in 1796, his sons attempted to make the Hutterites their serfs, and in 1802, on the advice of a Russian state representative, the Hutterites moved to Radichev, thirteen miles northeast on the Desna River. Although the community flourished initially, the death of the older brethren left a new inexperienced generation that was untried by tribulation and therefore less disciplined. In addition, the land in Radichev was of poor quality and unable to support the population. Conflict resulted and a split developed over the practice of community of goods.

The group led by Jacob Walter, which wanted to abandon this practice, took its share of the property and moved almost six hundred kilometres south to settle near Mennonites at Chortitza. Later at Radichev, a fire in 1819 destroyed most of the buildings, and the remaining property was divided up among those who had remained.

Upon hearing of the dissolution of the community of goods, Walter’s group returned to Radichev. Some large buildings were used communally, but the land and livestock were divided among the fifty families who now lived individually. Half of these families moved across the Desna River and the rest remained at Radichev.

After this, community life steadily deteriorated, and by 1842 many young people were illiterate. Under the guidance and supervision of the Mennonite reformer Johann Cornies, they moved 640 kilometres south to the Molotschna area, where they established the community of Huttertal, modelled after Mennonite villages. Learning modern farming methods from Mennonites, they soon flourished. Children attended village schools; adults attended night school.

Hutterites continued to elect their own ministers and to use the old sermons from the seventeenth century, though there was distinct uneasiness when ministers read the Pentecost sermons, based on the second chapter of Acts, with its description of living in common. In 1852 a second village was established and named Johannesruh in honour of Johann Cornies. By 1868 there were five Hutterite villages, including Hutterdorf and Scheromet.

In 1859, as a result of the efforts of three ministers, Jacob Hofer, Michael Waldner, and Darius Walter, and a miraculous vision experienced by Waldner, the practice of community of goods was renewed, forty years after it had been abandoned. Waldner and Walter each established communal living in Hutterdorf, one group at either end of the village. In the centre were those who continued to live individually, led by their minister Jacob Wipf, a teacher.

In 1864, the Russian state began to introduce a series of reforms that transformed Mennonite and Hutterite communities. An edict was enacted that made Russian the language of instruction in schools, and a few years later the state announced it would establish universal military service. A delegation of Mennonites, and Hutterites travelled to North America to investigate settling there. Paul and Lorenz Tschetter were the Hutterite representatives; Paul, a minister, and Lorenz, his nephew, were from a noncommunal Hutterite group. Paul kept a diary of this journey, from April 14 to June 27, 1873. On June 7, 1874, the two groups of Hutterites who were living communally boarded the SS Hammonia in Hamburg, Germany, arriving in New York on July 5.

Lorenz Tschetter returned to Russia specifically to persuade minister Jacob Wipf and the people of Johannesruh to immigrate to the United States, which they did in 1877, but it was 1879 before the last of the noncommunal Hutterites left Russia. In the United States, Michael Waldner’s group became known as “Schmiedeleut,” because he had been a blacksmith (Schmied), Darius Walter’s group became known as “Dariusleut,” and Jacob Wipf’s group became known as “Lehrerleut,” because he was a teacher (Lehrer).

* * *

Michael Mändel (b. 1833) and his wife, Anna Waldner (b. 1832), were in the noncommunal group. They were married on November 21, 1853, and had seven children. Jacob (1855), Maria (1860), Anna (1862), Michael (1865), Johann (1867), Joseph (1868), and Paul (1871). Jacob’s birth occurred thirteen years after the move to the Molotschna area, so he and his siblings attended school and benefitted from the rich, rural lifestyle made possible by the South Russian climate, the fertile land of the steppe, and the gardens and fruit-tree planting program organized and imposed by Johann Cornies. They learned livestock production and had contact with other people of German background – in contrast to the isolation they experienced in Radichev. Years later, in North America, these siblings would reminisce and relate to their grandchildren their heartbreaking farewell to the trees whose growth they had helped foster by watering and weeding. The trees had just begun bearing plums and pears when the Mändel family abandoned them.

After the marriage conversation with his father, Jacob naively – or cleverly – brought it up again. Again, Michael Mändel suggested that Jacob speak to Sohn (an abbreviation of the name Susanne), the widow.

“She has three children and she is nine years older than me!”

“Yes. She is a brave woman and good and klug [smart] – and she has a property!”

When Jacob continued to waffle, his father responded with an order: “Go and harness our horse to the wagon. We are going to visit Sohn!”

Together they drove over to make their proposal, and Sohn accepted. On November 2, 1874, Susie Kleinsasser and Jacob Mändel were married. On August 26, 1875, a daughter, Anna was born to the Mändels, but she died in infancy. Their son Jacob was born on November 28, 1877.

Like many of the noncommunal Hutterites, Jacob and Sohn homesteaded a quarter section of land in Hutchinson County, South Dakota, ostensibly with the intention of doing it for the colony (a term used in America for Hutterite communities where communal living had been established). There is evidence that Sohn expressed some concern about being on their own, away from the colony. Homesteaders were required to break the land, dig a well, and build a fence or a house during their first year to lay legal claim to it. Jacob promised Sohn that it was temporary, and he would return to the colony when she wished.

It was the ideal life for Jacob; he relished the freedom and the interaction with his non-Hutterite neighbours. His language became colourful and he took up smoking. When the year of homesteading was over, he was far from ready to settle down in a Hutterite colony. “There is plenty of time,” he assured Sohn. The story has it that he even placated the colony minister by signing over ownership of the homesteaded land to the colony while continuing to enjoy his freedom.

One day Sohn gave Jacob an ultimatum. Sohn’s three children, Susanna (1867), Paul (1869), and Maria (1871), were approaching adolescence. She had watched her children returning from school and it struck her how happy and comfortable they were as they laughed and chattered with their non-Hutterite schoolmates. “Jacob,” she said, “it’s now or never that we return to the colony. If my children marry non-Hutterites, I am not returning to the colony!” It is not difficult to picture Jacob sadly smoking a final pipe before beginning preparations to move. “Good,” he told Sohn that Sunday. “Get everyone ready. We are driving to Bon Homme Colony in time for church!” At Bon Homme he formally requested of the minister to join and was accepted. Later when they visited their Lehrerleut relatives at Elm Spring Colony, they were aghast. “Why would you join a Schmiedeleut colony? They hardly have anything to eat!”

“They live a more genuine communal life, though!” Jacob retorted.

Jacob and Sohn had five more children: Michael (1880), John (1882), Joseph, (1886), Peter (1888), who died in infancy, and Anna (1891).

Jacob made his presence known in the colony. Once, during winter woodcutting, the minister of the colony called a brotherhood meeting to deal with an infraction by one of the men. As was customary, another brother was sent to call him to the meeting, but he refused the summons. Later, out in the woods, Jacob saw this recalcitrant brother working among the trees. Picking up a stout stick, Jacob walked over to him and said, “Listen! The next time you are called to Stübl (a brotherhood meeting), I would suggest you respond. Otherwise, you and I will deal with the matter back here.” He brandished the stick sternly in the man’s face. Thankfully, the brother complied.

Another time, Jacob was at the colony mill watching the water flowing beneath the huge wheel, not high enough to turn it. After studying it for a while, he announced, “We can easily fix this by damming the flow downriver!” He was right. By strategically erecting some boards, the water was trapped, and the raised water turned the millwheel.

Later, however, Jacob Wipf, the Lehrerleut elder complained that damming the river that way effectively prevented his colony from harvesting the fish as before. Not a popular man, Wipf never spoke the Hutterian dialect. Instead, he always spoke the standard High German he had learned in a Mennonite school, which gave him a haughty air. When he heard that damming the river was Jacob Mändel’s doing, he expostulated in impeccable German, “Ober Jakob! Du hast uns unsere Fische beraubt! Du verstehst doch, wo die Fische herkommen?” (Goodness Jacob, you have robbed us of our fresh fish supply! Surely you understand where fish come from?)

Jacob replied, “Jo, ich weiss es – von unter deiner Tuchet kummen sie!” (Yes, I understand! They come from underneath your feather quilt!)

When our Fairholme uncle John told us this story, he always chuckled and added, “It was not a nice reply at all, but …”

In 1914, just four years before the Hutterites immigrated to Canada, Sohn Ankela (Grandmother Susanne) passed away at the age of sixty-eight, and was buried in the cemetery at Rosedale Colony, near Mitchell, South Dakota. A year later, on June 13, 1915, Jacob married Anna Waldner, a Lehrerleut woman. They had one daughter, Rebecca.

In his senior years, Jacob found his forced inactivity difficult and spent as much time as possible sitting outside. One summer day, he was enthralled by an oriole singing in a tree right by his house. Calling his grandsons over, he instructed them to go to the horse barn and pluck some long hairs from the horses’ tails. When they returned with these, he tied them together to create a snare. Then he told the boys to place the noose on the grass and place some worms inside it as bait for the oriole. “Now give me the other end,” he asked, and sat patiently holding it. Later, when the oriole hopped over to eat the worms, he pulled the end of the horsehair string and caught it. Then he placed it in a cage inside the house and waited for it to sing as beautifully as it had outside. To his great disappointment, the bird remained silent, and he sadly let it go again.

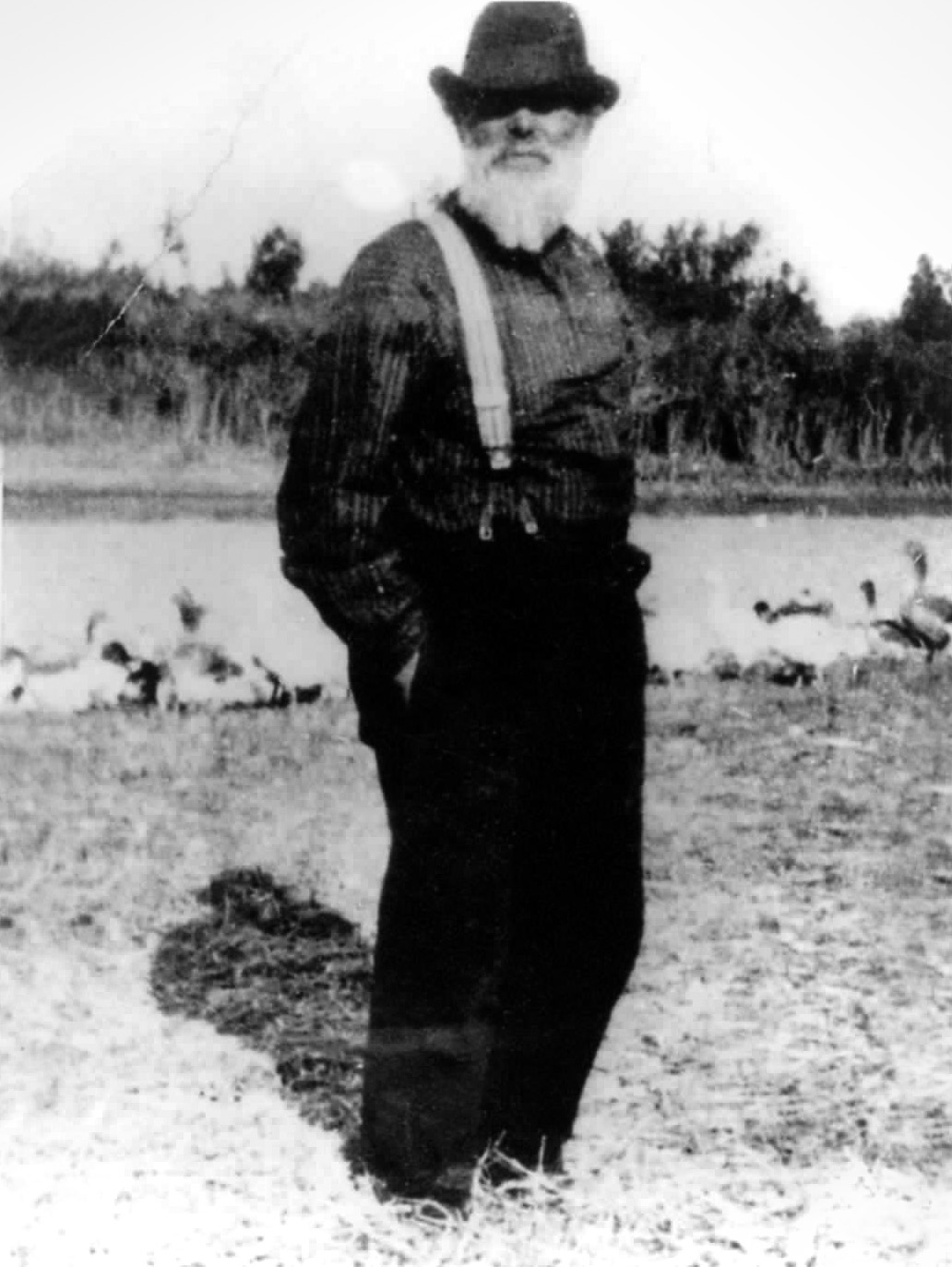

Jacob Mändel died on August 16, 1934. He is buried in the cemetery at Rosedale Colony, Elie, Manitoba. He was the patriarch and Sohn was the matriarch of the Maendel Hutterian families in Manitoba.

Dora Maendel grew up in the New Rosedale Hutterite Colony, but lives and teaches in the daughter colony of Fairholme, near Portage la Prairie, Manitoba. She heard the story of her great-grandparents Sohn and Jacob from her local aunt and uncles, and from Maendels in far-flung colonies.