A Pandemic in Saskatchewan

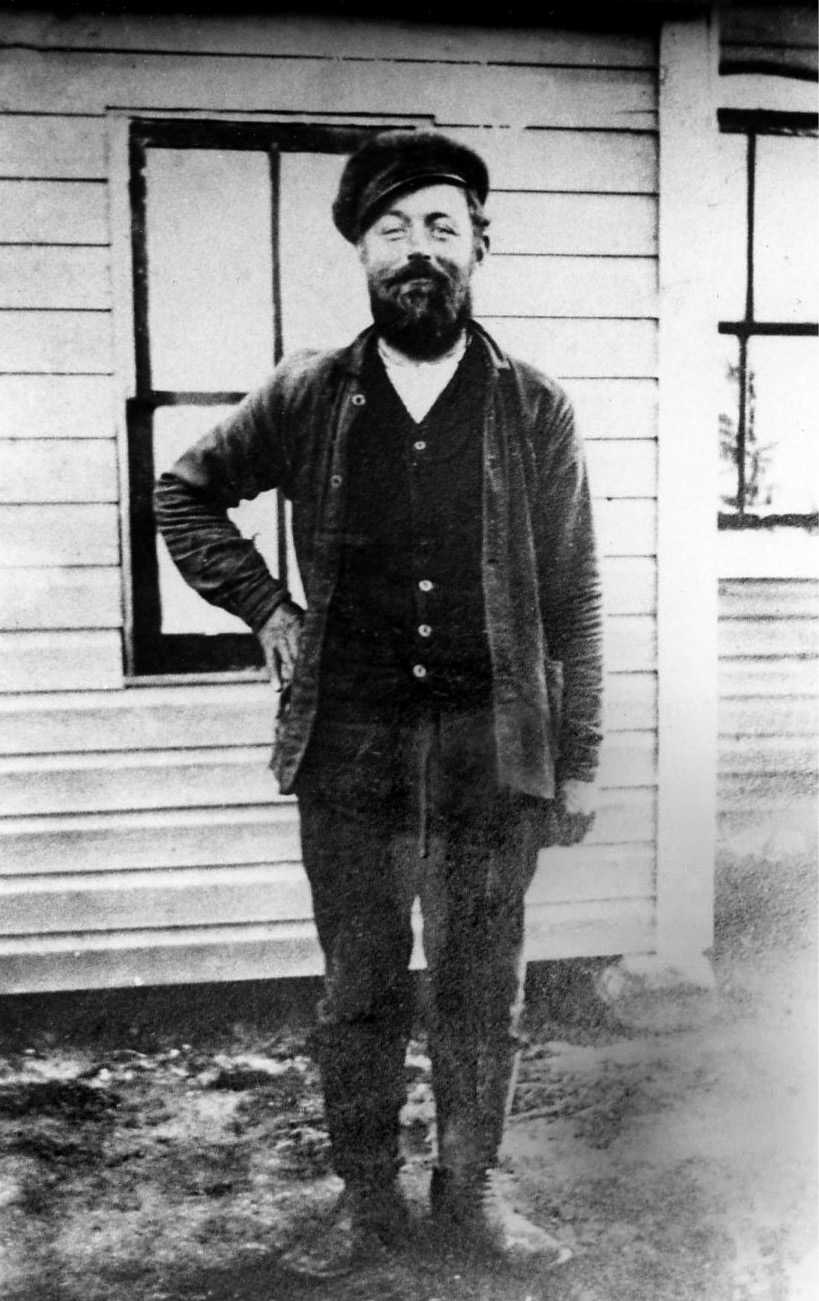

Leonard Doell

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a catalyst for people searching to understand the effects of past pandemics and epidemics on the world.1 It is an opportunity to explore how individuals and communities, including faith communities like the Mennonites, survived and responded to past health crises. How Saskatchewan Mennonites experienced the 1918–1919 flu pandemic raises some interesting parallels to our present situation.

When the First World War ended on November 11, 1918, a new war against a deadly flu had already begun in Saskatchewan. The saying “after war comes the plague” held true in this case.2 The flu pandemic arrived in three waves: the spring of 1918, the fall of that year, and then the spring of 1919. Saskatchewan was hardest hit in the fall of 1918. In Saskatoon, the city shut down, with the closure of schools, churches, and a ban on meetings in public spaces.3 The 1919–20 annual report of the Saskatchewan Department of Public Health put the number of deaths at 3,906 from October to December 1918. During 1919–20, 1,010 more deaths took place. Many of these deaths occurred in the 20–40 age bracket.4

The flu spread primarily among young adults, bypassing the oldest and youngest family members. People who seemed healthy suddenly developed serious symptoms. As Eileen Pettigrew describes: “The flu often began like a cold, with a cough and a stuffy nose, progressing to a dreadful ache that pervaded every joint and muscle, a fever that shot as high as 104 degrees and a marked inclination to stay in bed. If it stopped, the patient was usually back to normal in a week but when it developed into pneumonia the outlook was grave indeed. With no antibiotics to rely on, doctors could only turn to their time-honored cures: rest, liquids and lots of hope.”5

Mennonite Experiences

The pandemic was one more event that created significant hardships for Mennonites. The First World War had created a strain between Mennonites and the Canadian government, as well as with their neighbours. Mennonite church leaders were trying to affirm conscientious objector status for their young men to keep them out of military service. There was intense pressure for Mennonites to purchase Victory Bonds, which they did after receiving assurances that their contributions would go towards alleviating suffering rather than abetting the war machine. And Old Colony, Bergthaler, and Sommerfelder Mennonites were being prosecuted through fines and jail sentences for not sending their children to English public schools.

In 1918, the Mennonite population in Saskatchewan consisted of pockets of settlers in rural areas. Two Mennonite reserves had the bulk of the population: the Hague-Osler Reserve, stretching from Warman to Rosthern, including Aberdeen, and the Swift Current Reserve, with lands south of Swift Current extending to Wymark, including Dunelm. Other concentrations of Mennonites could be found in Herbert, Rush Lake, and Waldeck; Drake and Guernsey; Borden, Great Deer, and Arelee; Carrot River and Lost River; Dalmeny, Langham, and Hepburn; and the Laird and Waldheim area. Few Mennonites, if any, had moved into cities by this point.

When the flu appeared, Mennonites were hit particularly hard. They tended to live in tight-knit communities and had large families, which made it easier to pass along the disease to others. It arrived in the fall, at the end of the harvest season, which was a time of social gatherings including pig butchering. Many workers on threshing crews became sick, which disrupted their work and income. It was also the time for celebrating communion in Mennonite churches, which was done with a common cup. As the epidemic raged into the Christmas season, extended family gatherings created further

opportunities for the flu to spread.

I searched the Old Colony Mennonite and Bergthaler Mennonite church registers from the Hague-Osler Mennonite Reserve for the number of deaths that occurred in 1918 during October, November, and December. In total, 92 people died during this period, which is one person per day. I assume that not all of these people died as the result of the flu, but out of 92 deaths, at least 76 took place in the month of November, at a rate of 2.5 deaths per day. The average age of death was nineteen years. While single males and females were affected, so were many young mothers and fathers, who left small children behind. It is not clear why some Mennonite villages and families were hit harder than others. These statistics do not include Mennonites from other churches who lived in the area, or non-Mennonite deaths.

Mennonite Responses

The community of Rosthern was hit by the flu in the middle of October 1918. On October 17, 1918, the Rosthern Enterprise (predecessor to the Saskatchewan Valley News) reported that the first victim of the flu in Rosthern was a man who had recently returned from Winnipeg, where he contracted the disease. The following week, the paper reported that the Rosthern school had been closed on October 23. On October 31, 150 cases of the flu were reported in the district and the first death had occurred: Henry H. Kinzel. By November, nearly everything was shut down. To address the crisis, the school was repurposed as a hospital, with the front rooms being used as wards for the sick, while the north room was a temporary morgue.6

During this crisis, Rev. Gerhard Epp tended spiritually to many sick and dying people. In his diary, Epp recorded visiting this temporary hospital on November 12: “There was a large room with two rows of beds where all the severely sick lay, a very sad sight!” In one room he found John Janzen from Rosengart, who lay on his bed struggling for breath. Janzen recognized Epp and told him, “I know that I have a Saviour.” He died later that evening. The next day Janzen’s brother David sought advice from Epp regarding a funeral for his brother. The funeral was held on November 15 in the home of Janzen’s parents Abram and Aganetha at Rosengart. Both parents were sick in bed, as well as other children. Epp conducted the funeral and Janzen was buried in the Eigenheim Cemetery, west of Rosthern.7 Rev. Epp would become sick during the pandemic, passing away in April 1919.8

In his history of the Eigenheim Mennonite Church, Walter Klaassen noted the helpful role of the church, and in particular, Rev. Epp, during this time: “Rev. Epp walked through the immediate neighborhood of the church to minister to the sick in every household. His daughters Judith and Helena assisted in caring for the ill in several homes and then also became ill. In Friedensfeld, where four members of one family died within one week, a trio of men made themselves responsible for dealing with the unprecedented emergency amongst their own people but also among their non-Mennonite neighbors. Johan Andres made the caskets, Bernard A. Friesen arranged for the funerals and minister Johan A. Dueck comforted the sick and dying and saw those who died to the grave. They did many funerals together, remembers Helen Friesen Letkeman. The Eigenheim community seems to have been spared the worst ravages of the epidemic.”9

On November 28, 1918, the Rosthern Enterprise reported that the emergency hospital located in the public school was closed. As the article explained, “The hospital has done its duty – it is creditable to Rosthern that it was opened up, and has no doubt been the means of lifting a great cloud of anxiety off the minds of quite a number, where all, or practically all, were sick in a home. To all those who volunteered to assist in any way and those who were instrumental in opening up, a hearty vote of thanks is due from the town and district. The school building has been fumigated and disinfected and it is expected to open again next Monday.”10

After the emergency hospital closed, church groups in Rosthern organized services of thanksgiving. According to the Enterprise, the Lutheran church planned to hold a service along with communion. The newspaper described how “the church is going to be decorated in evergreen . . . and the pastor expects every member to be present to join the nation in thanks and praise to Almighty God for the conclusion of the war and restoration of peace.” A special funeral service was also planned in memory of the ten members of the congregation who had died of the flu.11 The Rosthern Mennonite Church also organized a well-attended thanksgiving service. It had been a month since the church had met due to the pandemic. Rev. Johan Dueck gave a sermon “offering God thanks” and Rev. Gerhard Epp spoke on Psalms 46. Rev. Kornelius Ens led the group in a closing prayer.12

In the town of Langham, officials responded in a similar way to the emergence of the flu. Schools, churches, and the poolroom were quickly shut down at the end of October.13 The school would be closed for three months.14 These preventive measures were not enough to help the Peter C. Epp family. The Epps’ youngest son, Diedrich, passed away at the age of eighteen, “after being ill for a few days, [with] an illness marked by a high fever, coughing and severe aching.” He was soon followed by their married daughter Katherine Wheeler, who left behind her husband George and eight young children. Peter C. Epp and his wife buried both children in the Langham Cemetery.15

The influenza hit other areas of the province. In Waldheim, when the flu broke out, the school and the local hotel were used to house the sick. Helene Warkentin recalled how “her parents and family stayed in the hotel and her father died there of the flu. They had as many as three coffins there at one time with the dead in them, standing in the lobby and waiting for burial.”16 The Henry H. Dyck family, who had moved from Corn, Oklahoma, to Waldheim as a consequence of the United States joining the war, also ended up in this thirty-room hotel. The family remembered that many people in the hotel were sick with the flu. Luckily the family did not contract it.17

Six members of the North Star Mennonite Church in the Drake area died of the flu. This church, established in 1906 by Mennonites arriving from Kansas and Oklahoma, had to close during the pandemic. Unable to hold funeral services inside the church, at least one was held outside.18 In the Dalmeny community, Anna (Peters) Thiessen suffered a tremendous loss when her husband, Wilhelm, a

popular, gifted, and highly respected teacher, died of the flu in November 1918, after a few months of marriage.19 The newspaper Der Wahrheitsfreund offered the following words of comfort: “God’s ways are often for us as people very dark but someday we will understand.”20

In the town of Herbert, the spread of the flu became serious by October 1918. The town council recommended that public facilities be closed. In the stores, people wore masks. A special constable, Anthony Haughlin, ensured that people followed the rules. Many people pitched in to help with the sick, including Dr. Funk, who often slept in his car as he tended to patients. Local women with training as nurses and midwives also helped as the town hall was converted into a hospital. With some men sick and others still at war, farmers had a difficult time bringing in the harvest.21

Good Samaritans

In nearly every community in Saskatchewan there were good Samaritans who helped their neighbours, at risk to themselves. In some cases they were trained medical people, but most of the time they were simply caring lay people. Johan and Margarete (Flaming) Strauss moved to the Brotherfield area near Hepburn from Kansas at the turn of the century. Since the doctor was in Saskatoon, Johan used his lay medical knowledge to help neighbouring families cope with the flu. As he travelled to neighbouring homesteads, his wife and children kept the farm going.22

Ministers performed an important role by offering spiritual comfort to the sick and their families during home visits. In the community of Arelee, Rev. Luka Krowchenko, who served as a minister in the local Mennonite Brethren church, struggled to keep up this work. Krowchenko related to his family that during a home visit he discovered “the husband dead in bed and the wife too sick to move to care for herself or inform anybody of his death.”23

Funerals were conducted daily. The dead were buried as soon as possible and sometimes with more than one person in the grave. In the village of Chortitz, Jacob Reddekopp and Peter Fast were buried in one grave, and Mrs. Heinrich Goertzen and her nephew Peter Reddekopp were placed together in another. Many volunteers were needed to dig graves in the frozen ground; some were themselves also weak from the flu. A resident of the Dunelm district recalled “dark days when death stalked up and down the land. The air was cold and foggy, the earth was bare and brown with no snow. Anyone with strength was on hand to help dig graves. With picks they chipped away at the hard sod. Sometimes a grave was not even completed before another person died. The men instead of digging another whole grave would broaden the base at one side at the bottom of the grave so that there was enough room to slide a casket into the cave-like hollow. Then there was space for the second casket as well.”24

Linda Buhler of Manitoba has done extensive research on Mennonite burial customs. She discovered that the Greenland Church of God in Christ (Holdeman) burial patterns during the 1918 flu epidemic were “different in the way that coffins used at the time were constructed with a glass panel in the lid so the viewing could take place through the rectangular or oval insert.”25 As she explained, “the coffins were often fabric covered and were built with higher sides so that viewing was only from the top. . . . The glass panels being used [permitted] viewing without opening the coffin. A number of people from the Greenland area remembered these as well, seemingly when people had died of infectious diseases.”26 More research needs to be done to see if the Holdeman Mennonites in Saskatchewan used the same burial practices.

During this difficult period many Mennonites tried to help their neighbours. According to their daughter, Johan and Maria (Bergmann) Braun made a strong effort to care for their neighbours near their homestead at Lost River. Johan would visit nearby houses to make sure that the basic needs of people and animals were being met. At the home of H. G. Neufeld, he found the parents unable to care for their young baby. Johan took the boy home to his wife. As his daughter Tina remembered, “If you ever saw excited kids, [it was us with] a little boy among five girls. ‘When is it my turn to hold him?’ I am sure we figured this was the biggest blessing on this side of heaven. Our father never got the flu, he was too busy doing chores for the neighbors. Mother did not get the flu because she was pregnant.” Others were not so fortunate. As Tina recalled, “I well remember in February 1919, Anna Neufeld, a ten-year-old girl, died from the flu. Some men were able to make a coffin and I went along with my mother to see her dress the corpse. I wanted to see what had happened to my playmate. Houses were left without a mother, the next one without a father, almost entire families were wiped out or maybe one small baby would remain. All you need to do is visit the cemeteries and they tell the tale.”27 The two local grave diggers, John J. Neufeld and Abram S. Bergen, had to dig twenty-one graves over the course of only a few weeks.28

Home Cures

People often attempted to use home cures to alleviate the symptoms of the flu. Tina Peters recorded that Mennonites used a specific recipe of “onions cooked in milk, cooled slightly and then thickened by adding rye flour. It was spread between cloths to form a poultice and applied to the chest as hot as the patient could bear. With continued applications, relief of the congestion was usually achieved in an hour.”29

The Gerhard and Maria (Heppner) Neufeld family, who homesteaded at Lost River, told the story of how, after beings very sick for days, Gerhard announced he craved fresh fish. According to family lore, “he went to the river, chopped the net out of the ice, [and] came home covered with ice and five fish. After a good feed he regained his strength and was able to do the chores, and to bury the dead.”30 The daughter of Herman and Katharina (Dyck) Unger recalled how the family was spared “the flu because we all had to take a good dose of red liniment every night.”31 Jacob Hildebrandt, a young talented druggist and businessman in Hague, thought brandy might protect him from the flu. Unfortunately, it did not work. His death was a huge loss to his wife and eight children and the wider community.

Conclusion

Most sources state that the 1918–19 flu killed fifty thousand people in Canada and fifty million worldwide. Maureen Lux places the number of deaths in Saskatchewan at five thousand, with one in four experiencing the flu.32 As she describes: “The peak of the epidemic came in November 1918, but there were more than 1,000 flu deaths in 1919 and a further 102 in 1920. It took twenty months before the epidemic finally waned. Northern areas, unaffected by the 1918–1919 wave, were attacked in the 1920s. The effects of the epidemic reverberated throughout the province. There were increased calls for rural hospitals and plans for university courses to train women in nursing and housekeeping. There were demands for more efficient public health care in Saskatoon, where the brunt of the fight against the flu was carried by volunteers. And nationally, a Dominion Bureau of Health was established in early 1919.”33

Vanessa Quiring observes that the mortality rate for influenza in the general population of Canada was 6.1 per 1,000. However, among Mennonites in Hanover, Manitoba, she found the mortality rate was more than double at 13.5 per 1,000. She argues that patterns of socializing account for the higher rates of deaths among Mennonites.34 Figures for Mennonites in Saskatchewan, and patterns of transmission, were likely similar.

Leonard Doell is retired and lives near Aberdeen, Saskatchewan. He is an active member of the Mennonite Historical Society of Saskatchewan and enjoys doing genealogical research and learning about Mennonite and Indigenous history.

- A version of this article was previously published as “Saskatchewan Mennonites and the Spanish Flu of 1918–19,” Saskatchewan Mennonite Historian 26, no. 1 (2021): 1–13. ↩︎

- Eileen Pettigrew, The Silent Enemy: Canada and the Deadly Flu of 1918 (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1983), 5. ↩︎

- Maureen Lux, “The Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918–20,” Green and White, Winter 1989, 14–15. ↩︎

- Saskatchewan Bureau of Public Health, Annual Report, 1919–20 (Regina: King’s Printer, 1921), 125. ↩︎

- Pettigrew, Silent Enemy, 16. ↩︎

- Rosthern Enterprise, Oct. 17, 23, and 31, 1918. ↩︎

- Rev. Gerhard Epp diary, Mennonite Heritage Archives (Winnipeg), vol. 1079, file 21, p. 203. ↩︎

- H.T. Klaassen, Birth and Growth of Eigenheim Mennonite Church, 1892–1974 (Rosthern, SK: Eigenheim Mennonite Church, 1974), 30. ↩︎

- Walter Klaassen, “The Days of our Years”: A History of Eigenheim Church Community: 1892–1992 (Rosthern, SK: Eigenheim Mennonite Church, 1992), 47. ↩︎

- Rosthern Enterprise, Nov. 28, 1918. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Rev. Gerhard Epp Diary, 204. ↩︎

- Minutes of the Langham Town Council, 1918, photocopy in the author’s possession. ↩︎

- Mary Nickel, “History of Langham Schools,” in Langham & District History, 1907–2007 (Langham, SK: Langham and District History Book Committee, 2007), 570. ↩︎

- Mary (Epp) Nickel, “Stories of John P. Epp,” unpublished article in the author’s possession. ↩︎

- Waldheim Remembers the Past (Waldheim, SK: Waldheim History Committee, 1981), 433. ↩︎

- Ibid., 141. ↩︎

- Drake, Past and Present: Making Memories (Drake, SK: Drake History Book Committee, 1987), 25. ↩︎

- Margaret (Peters) Ens, “Henry and Maria (Harder) Peters), in Search for Yesteryears: A History of Newfield School and Districts of Elkhorn, Little Bridge, Murphy Creek, Newfield and Teddington (Codette, SK: Newfield School and Districts History Book Committee, 1984), 445. ↩︎

- Der Wahrheitsfreund, Nov. 27, 1918. ↩︎

- Bittersweet Years: The Herbert Story (Jostens Canada, 1987), 175. ↩︎

- Our Rich Heritage: Hepburn and Districts (Hepburn, SK: Hepburn History Book Committee, 1994), 645. ↩︎

- The family, “Rev. Luka and Barbara Krowchenko,” in Reflections: A History of Arelee and the Districts of Balmae, Dreyer, Golden Valley, Light, Petroffsk, Raspberry Creek, Sunnyridge and Swastika (Arelee, SK: Arelee and District Historical Association, 1982), 213. ↩︎

- Helena Hildebrandt, “Jacob P. Hildebrandt Family,” in Patchwork of Memories (Wymark, SK: Wymark & District History Book Committee, 1985), 179. ↩︎

- Linda Buhler, “Mennonite Burial Customs: Part Two,” Preservings, no. 8, part 2 (1996): 50. ↩︎

- Linda Buhler, “Mennonite Burial Customs: Part Three,” Preservings, no. 10, part 2 (1997): 79. ↩︎

- Tina (Braun, Neufeld) Gollan, “Johan J. and Maria (Bergmann) Braun,” in Search for Yesteryears, 264. ↩︎

- Helen (Neufeld) Enns, “John J. and Helena (Neufeld) Neufeld,” in Search for Yesteryears, 329. ↩︎

- Tina H. Peters, “Remedies,” in Mennonite Memories: Settling in Western Canada, ed. Lawrence Klippenstein and Julius G. Toews (Winnipeg: Centennial Publications, 1977), 246. ↩︎

- Susan Neufeld, “Gerhard H. and Maria (Hoeppner) Neufeld,” in Search for Yesteryears, 346. ↩︎

- Tena Rempel, “Herman Unger Family,” in Our Treasured Heritage: Borden & District (Borden, SK: Borden History Book Committee, 1980), 319. ↩︎

- Lux, “Great Influenza Epidemic,” 14. ↩︎

- Ibid., 16. ↩︎

- Vanessa Quiring, “Mennonites, Community and Disease Mennonite Diaspora and Responses to the 1918–1920 Influenza Pandemic in Hanover, Manitoba,” (Master’s thesis, University of Manitoba, 2015), 37. ↩︎