Call for Artefacts: Mennonite Emigration from Canada to Mexico

Andrea Klassen

On March 8, 1922, the first train carrying Mennonites from Canada arrived in the Mexican town of San Antonio de los Arenales (now known as Cuauhtémoc). During the 1920s nearly eight thousand Mennonites from Old Colony, Sommerfelder, Bergthaler, Chortitzer, and Kleine Gemeinde communities would leave Manitoba and Saskatchewan for northern Mexico and, beginning in 1926, for Paraguay.

In 2022, Mennonite Heritage Village, in partnership with the Plett Foundation and the Mennonite Historical Society of Canada (MHSC), will be marking the hundredth anniversary of this milestone event with an exhibit focusing on the story of Mennonite emigration from Canada to Mexico. The planned exhibit will be displayed in the Gerhard Ens Gallery at Mennonite Heritage Village from May to November 2022. After this initial display, a smaller version of the exhibit will be made available to host organizations across Canada. We aim to reach communities that are important to this history, including those with descendants of the original migrants who have returned to Canada in recent years.

This exhibit will highlight the factors that led to Mennonite emigration. In 1874, Mennonites arrived in Canada from Russia after receiving special privileges from the federal government. The concessions included the freedom to educate their children as they saw fit, according to their religion and in the German language. Those freedoms were upheld until 1916, when the Public Schools Act in Manitoba was amended making attendance at publicly inspected, English-language schools compulsory for all children between the ages of seven and fourteen. Saskatchewan followed with similar legislation a year later. Not willing to give up their freedom of education, Mennonites in Manitoba and Saskatchewan petitioned their provincial governments for the right to continue with their German-language, private schools. When this effort failed, Mennonites refused to send their children to the government-run district schools, often facing steep fines, confiscation of property, and even jail time for their non-compliance.

Why was the question of schools so important to traditionalist Mennonites in Canada? Aeltester Isaak M. Dyck, writing in the 1960s about the migration, saw the new education legislation as having significance beyond what and how children learned in schools: “We were afraid that if we shared our schools – the place where seeds are first sown in the human heart – with the world, then our churches would not be able to remain separate. For in order to maintain the faith and a clear conscience, our forefathers were always travelling . . . and now we too have come into the position where we could no longer remain in Canada with its public schools that were forced upon us with prison sentences and fines. Our forefathers always took the school question very seriously, because they understood well that what the school is, the church will become.” At stake for these Mennonites was not just the future of education for their children, but also the freedom to practice their religion as a community.

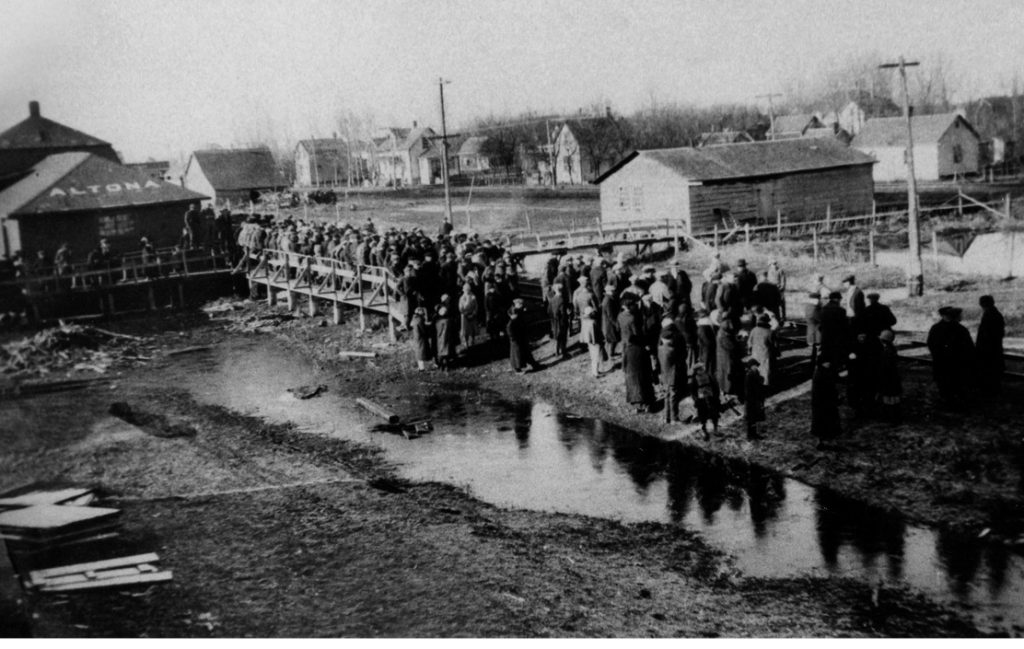

(MAID: MHA, PP-22 – PHOTO COL 639-20.0)

The exhibit will also explore how the departure of these traditional Mennonite communities had a profound effect on Canadian Mennonite life and identity. Non-Mennonites will learn the story, often untold outside of Mennonite circles, of how an ethnoreligious minority group left Canada over matters they considered crucial to the exercise of their religious freedom. Their migration challenges the narrative of Canada as a peaceful haven for ethnic and religious minorities. It is a story about competing conceptions of religious freedom, and of tensions between religious, linguistic, and educational rights on the one hand, and the obligations of citizenship on the other.

The legacy of this migration was also felt throughout Latin America, and in the United States as well. The move to Mexico marked the beginning of a vast transnational network of Mennonite communities spread throughout North, Central, and South America. Canada has seen the return of Mennonites from these communities, especially in southern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta.

The travelling exhibit is currently in development and will be available to travel to locations throughout Canada from December 2022 to December 2024.

Do you have historical documents related to the Mennonite migration to Mexico?

Mennonite Heritage Archives is looking for archival materials that tell this story, including oral interviews, photos, correspondence, diaries, and journals.

Contact Conrad Stoesz at cstoesz@mharchives.ca

Do you have an object with a story to tell about this history?

Mennonite Heritage Village is looking for artefacts, which could include clothing, items related to farm and home life, travel items, toys, or any other item with a story to tell that relates to the emigration of Mennonites from Canada to Mexico.

Contact Andrea Klassen at andreak@mhv.ca

If your organization is interested in hosting the travelling exhibit, which will to travel to locations throughout Canada from December 2022 to December 2024 please contact the co-chair of MHSC’s Canadian Emigration Commemoration Committee for more information.

Contact Jeremy Wiebe at treasurer@mhsc.ca