A Mennonite Matriarch: Maria Kehler Lemke Janzen

Pam Klassen

A trail of correspondence published in the newspaper, Die Mennonitische Rundschau connects the descendants of Michael Kehler (b. 1779) and Elisabeth Loewen (b. about 1783). Established in 1880, the Rundschau was an inter-continental Mennonite German-language newspaper that contained dedicated space for personal letters and, as such, functioned like a social media platform for the Mennonite diaspora. In this trove of personal letters, we can find an engaging narrative about Michael and Elisabeth’s daughter, Maria Kehler, and her married life in the Mennonite village of Gruenfeld (present-day Zelene Pole), in the Schlachtin colony. Relatively little is known about Schlachtin and the neighbouring Baratov colony, which together formed an administrative unit, in part because the records of the congregation have disappeared. Even less is known about its women. The Kehler letters, particularly when read in tandem with available memoirs of Schlachtin-Baratov, provide glimpses into typical events in the lives of women and show their critical labour that kept the community intact. Though Maria Kehler’s family story is by no means representative of all Mennonite women in tsarist Russia, it is a valuable account of one Old Colony matriarch and the people she loved.1

Early Childhood

Maria’s parents were children when they immigrated to New Russia (present-day Ukraine) in 1789. Elisabeth Loewen was about six years old when she accompanied her family to Neuendorf.2 Michael Kehler was around ten years of age when his family began the journey to Schoenhorst, then to Rosenthal.3 Both the Loewens and the Kehlers were among the original settlers at Einlage, the village where Michael and Elisabeth were married sometime in early 1803.4 By 1806, Michael owned his father’s farm.5 On November 6, 1814, at Einlage, daughter Maria Kehler was born.6 Maria was a middle child with eleven or twelve siblings.

The Kehlers belonged to the Mennonite church in Chortitza. As such, Maria and her siblings would have received a community-based induction into the faith, including the rite of adult baptism. Maria would have attended the village school, where she and her classmates received the prescribed Mennonite

curriculum. We know she could read because in 1905 her husband alluded to that fact.7

Michael Kehler likely died before 1850. It appears that his widow, Elisabeth, remarried a Peters. By 1852 she was widowed once again and was living with her son Gerhard Kehler, along with grandson Peter Blatz, in the district of Aleksandrovsk.8 It is possible that she died before 1859 because she does not appear on the subsequent register of people living outside of the Chortitza colony.

In Maria’s journey toward adulthood, she became acquainted with a young man named Johann J. Lemke, the son of Johann and Elisabeth (Arend) Lemke. He was born January 23, 1809, probably at Nieder Chortitza.9 After his father’s death around 1811, Johann J. was taken in by Jacob and Elisabeth (Nickel) Nickel of Kronsweide.10 Sometime between 1832 and 1837, Johann Lemke and Maria Kehler were married.

Until the late 1840s, the Kehler-Lemkes appear to have lived in the Chortitza colony, probably in Kronsweide.11 Between 1837 and 1848, Maria bore nine children of whom five reached adulthood: Jacob Lemke (b. June 16, 1837), Maria Lemke (b. about 1841), Elisabeth Lemke (b. Sept. 6, 1843, at the Chortitza colony), Johann Lemke (b. Dec. 22, 1844, at Kronsweide), and Katharina Lemke (b. about 1848).12

In 1848, the Kehler-Lemkes left the Chortitza colony and, with permission from church and secular authorities, began farming land on the estate of Daniel Peters. They lived in their own home with their five children.13 Maria’s brother, Michael Kehler, and wife Anna were also farming on the Peters estate. Two years later, Johann Lemke was recorded at Kronsweide with the family of Jacob Nickel. In 1859, the colony register shows Maria and Johann Lemke and their five children residing on land belonging to Peters, along with brother Michael Kehler, who was listed with a younger wife named Helena.14

Maria Kehler Lemke’s years from early adulthood into mid-life contained much happiness, wrote grandson-in-law H. P. Peters. The family was close-knit, as depicted in correspondence published in the Rundschau. We can imagine that as an Old Colony mother Maria concerned herself with maternal work of raising children who were acceptable to her community. The family expanded: Jacob Lemke married Helena Janzen (b. Feb. 24, 1840), daughter of a Franz Janzen, who figures prominently in this story. This couple lived in the Yazykovo colony, then moved to the Schlachtin-Baratov area, settling at Gruenfeld. They had at least five biological children and several foster children.15 Their daughter Maria Lemke married Martin Johann Schmidt (b. about 1840), and they settled at Gruenfeld with two children.16 Daughter Elisabeth Lemke married Jacob Jac. Thiessen (b. Jan. 15, 1845) in the Chortitza colony, where they would settled at Einlage with six children.17 Son Johann Lemke was baptized on June 8, 1864, in the village of Chortitza, Chortitza colony.18 On February 2, 1869, he married Maria Johann Dyck (b. Jan. 20, 1848), and they settled at Neuenburg with nine children.19 On May 26, 1887, son Johann Lemke remarried to Sara Jacob Friesen (b. Nov. 21, 1856, at Neuenburg). They lived at Neuenburg and had at least five children.20 Daughter Katharina married Jacob Heinrich Martens and they settled at Gruenfeld. They had at least four children.21

Sometime in the 1860s, Johann Lemke passed away.22 He and Maria had been married for about thirty-three years. During this period of Maria’s life she also lost her sister Elisabeth (d. 1863) and her brother Phillip (d. 1871).23 In 1873, Maria Kehler Lemke married the widower Franz Janzen of Neuenburg, the father-in-law of her oldest son, Jacob Lemke.24 Little is known about Franz Janzen’s background. According to Franz’s own words, he was born on February 29, 1821.25 However, 1821 was not a leap year, so this birth date must be an estimate. He may have been the Franz Janzen of Kronsgarten (b. about 1822), son of Julius Janzen, whose family in 1836 transferred to Kronsweide.26 He also may have been the Franz Janzen of the Agricultural Commission who in February of 1872 helped supervise an auction at the newly purchased Baratov estate.27 As well, it is possible that he was the Franz Janzen of Ivanenko who purchased Rev. Jacob Epp’s property at Gruenfeld.28

Decades later, speculating about public reaction to the Kehler-Janzen union, grandson-in-law H. P. Peters wrote: “When Grandmother entered her present marriage, some of her friends, who have now been settled in the earth for a long time, probably thought that the arrangement would not last long, because by then she was already called ‘alte Lemkesche.’”29 And yet, much more life was ahead of the well-known fifty-nine-year-old bride. Her second wedding occurred during a time of great change in the Mennonite colonies: many Mennonites were preparing to leave tsarist Russia to homestead in a place they referred to as “America.” And so, as Maria and Franz Janzen became reaccustomed to married life, three of Maria Kehler Lemke Janzen’s brothers – Jacob, Johann, and Gerhard – joined the voyage across the Atlantic Ocean to colonize Treaty 1 territory in the newly formed province of Manitoba. Maria and Franz Janzen decided against leaving the Russian empire. The “push” factors of russification, landlessness, and conscription that likely influenced the emigrating Kehler brothers evidently did not induce the Janzens to migrate. Besides, for Maria, the “pull” factor of family must have been powerful, as none of her children emigrated. For the time being, the Janzens resided at Neuenburg, close to her son Johann Lemke and his family.30

Challenges in Gruenfeld

Sometime before 1877, Maria and Franz moved to the bare steppe at Gruenfeld, in the Schlachtin colony, an offspring colony of Chortitza.31 It is possible that the Janzens were among the first colonists in the street village, as three families with that surname are listed among the original families.32 Matrilocality may have played a role in this decision: Maria had other Kehler family members who lived in the area at a place called Ivannenky or Ivanenko, which was populated by Mennonites from the Chortitza colony. The authors of The Berliner Kehler Clan refer to this area as “Ivankov’s Land,” and states it was leased land that became known as Gruenfeld.33 The author of Aron Schultz’s obituary of 1924 used the name “Ivanyenkov’s Land,” stating that it was rented land at Gruenfeld; however, the writer may be implying that the area was settled prior to the official birth date of 1873 for the Schlachtin colony.34 Several Rundschau letters suggest that Ivannenky was located outside of Schlachtin and that it may have eventually been absorbed by the colony. Maria’s son Jacob Lemke, for instance, wrote that he lived at Ivannenky prior to moving to Schlachtin around 1877.35 Her brother, Michael Kehler, was also known to have lived on this estate.36 More research is needed to clarify the relationship between Ivanenko and Schlachtin.

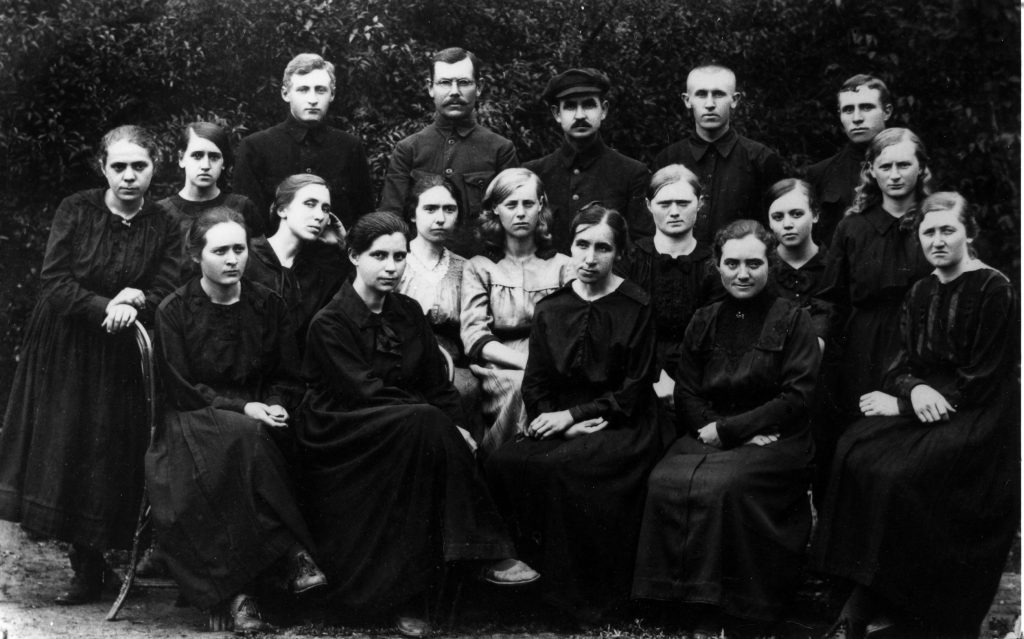

The Kehler family chronicle is a valuable glimpse into village life at Schlachtin.37 Located in the district of Krivoy Rog (present-day Kryvyi Rih), Schlachtin consisted of two villages, Steinfeld and Gruenfeld. Gruenfeld was located on the open prairie and was settled largely by colonists from Einlage who belonged mainly to the Kronsweide Gemeinde.38 At Gruenfeld the group became part of the Neu-Chortitza Mennonite Church. Maria and her fellow congregants met in homes, at the local school, and in machine sheds.39

There are many reasons why the colony should never have worked. How could a group of farmers succeed in an area far from markets and with inconsistent water access?40 At a place whose land purchase price, it was said only half-jokingly, included “the jackals which continued their Juliet-song by the windows at night”? In which the first baby had to be born in a sheepfold?41 The settlers’ horses ran back to the Old Colony during their first night at the new location. The first years were marked by failure. Former resident Walter Wiebe, in his address at Gruenfeld’s 130th anniversary celebration, described the initial conditions: “Many died of illness, cold, or malnutrition. At the beginning they lived in semlins, or sod houses. What they finally owned was hard to come by.”42

In 1875, the colony’s first crop failed.43 Two years later, a plague (perhaps blackleg) gripped the cattle. After the first death, Maria’s son-in-law Martin Schmidt took swift and innovative action: “He immediately blocked his driveway. His boys had to change their clothes every time they came from the village before going to the stable. He was also personally strict about this. If he went out, he changed his clothing before entering the stable. However, he managed to keep his herd from infection.”44 Consequently, with no small thanks to the women who washed baskets of extra laundry, the Lemke-Schmidt farm was spared. Otherwise, only a few calves remained in Gruenfeld.

In 1886, the colony was hit by total crop failure. The crop was so poor that many of the local farmers did not bother to harvest anything for themselves, let alone for their cattle. The Chortitza colony helped amid ongoing tension about the debt of Schlachtin colony.

The pioneer labour of Maria and her fellow Gruenfelders would not have been very different from that of her brothers who were homesteading half a world away, as documented in a variety of sources.45 Walter Wiebe described some of the hard work of the Gruenfeld colonists to replicate the good life as they had known it: “They operated exemplary businesses. They ran horse and pig breeding, and brought the famous German red cow, later renamed the Rote Steppenkuh. They had blooming gardens. On the streets they planted fruit trees and white acacia trees to bear honey. All of this led to prosperity.”46

In the mid-1880s a technological marvel arrived: the train. As a result, markets became available to the farming community. The Gruenfelders were conflicted about the change. Jakob Redekopp recounts how government officials had thought they were acting in the Gruenfelders’ best interest by building the railway station conveniently at the end of the village. The Gruenfelders, however, disapproved of the idea that their young people would have an easy way out. They would lose their children to the world! And so the government was flooded with protests. In response, the station was situated a few kilometres away and peace was restored. Critical to Maria Kehler’s story, this new form of transportation helped create a tangible link to the world: an increasingly accessible and reliable mail delivery system.

Whirlwind of Words

Toward the end of the 1880s, many of the Kehler siblings and their children began using the Rundschau to maintain family ties. The decision to take public the family correspondence was spurred in 1887 by Maria’s brother, Jacob Kehler of Manitoba: “Now, my dear ones, since the private correspondence between us seems to be an arduous matter, I ask you to entrust something to the dear Rundschau. She likes to take messages from friends with her on her round trip to delight others.”47 And so it was that the Rundschau was delivered and read and shared in the homes of Maria Kehler’s family, both near and far.

The sheer volume of published letters connected to the Kehlers may prove their legendary verbosity: the clan’s conversations spilled across hundreds of Rundschau pages, sometimes even with several missives per issue. Although Maria’s voice did not appear in the first person, others wrote on her behalf, and the Manitoba Kehlers of Sommerfeld (West Reserve) and Hochfeld (East Reserve) regularly and affectionately referred to their beloved married sister and aunt, Mrs. Maria Janzen, back in the old country. The correspondence contains priceless scraps about the everyday and the sacred in Maria’s life at Schlachtin: weather and farm reports, church news, and personal updates about births, deaths, marriages, changes in living arrangements, illnesses, and the daily workload.

The first Kehler-Lemke family contributor to the “group chat” was eldest son Jacob Lemke of Neuenburg, who was active in the Rundschau during the late 1880s and early 1890s.48 Jacob and his Kehler uncles in Manitoba bantered back and forth, accusing each other of not writing often enough, of forgetting each other’s existence, and even of being dead. In one letter from 1889, Lemke mentioned that he thought he’d read that a Johann Kehler in Manitoba had passed away.49 Lemke received the following swift and tart response (written in third-person perspective, no less): “Johann Kehler, Sommerfeld Man, tells his nephew that he himself, as well as all of his relatives who bear the name Johann Kehler, are healthy and well.”50 In fact, added Uncle Johann, he writes to his nephew Lemke faithfully every year and hears nothing in return!

When reporting about his mother, Jacob Lemke wrote most regularly of her illnesses. During at least three consecutive winters his mother was sick with various diseases that swept through the villages. In early 1889, Lemke reported that “except for our mother, we are all in good health.”51 However, he mentioned that his “old Aunt Blatz,” Maria’s sister, who had been living with his family, was unwell and “quite weak.”52 A few months later, toward the end of March 1889, Jacob and Helena Lemke’s son-in-law Abraham Wiens passed away due to an unknown cause, leaving behind his devastated and ill young wife.53 It was around this time that the Kehler-Janzens moved temporarily back to Neuenburg. The reason for the change is unknown but illness may have been a factor.

Next, Maria was sick for the entire winter of 1889–90, perhaps with the influenza that son Jacob said had swept the area. He acknowledged that he also had been so ill with the flu that he could not go outside to do chores. By early April, his mother was well enough again to be out and about. Jacob said, in fact, that on April 8 his parents came from Neuenburg, where they were still living at the time, to visit him at Gruenfeld.54

The following winter, yet again, Maria’s name appeared on a sick list published in the Rundschau. In a December 1890 letter, son Jacob shared his worry about his seventy-six-year-old mother’s condition: “My dear parents were guests here in August and . . . we were their guests in mid-September. Now we have found out that dear Mother is sick. But we do not know the exact details; we would have been there already, but the way to Neuenburg is over 100 Werst, which is no small thing in winter.”55 One can only imagine how difficult frequent illnesses were on a female colonist like Maria, given the heavy daily workload she would have experienced on the farm.

However, Maria recovered and was well enough the following year to leave her Neuenburg home, together with her husband, to stay with son Jacob on his farm more than a hundred kilometres away. The reason for the visit may have been Jacob Lemke’s poor physical condition. Since about the time his three Kehler uncles sailed across the ocean, Jacob had suffered from an unspecified illness. Around 1891, Franz and Maria Janzen went to Gruenfeld to stay at their son’s home and, while Maria was helping with the farm work, she had the misfortune of breaking her left arm. “As far as we know,” wrote Lemke the following year, “it’s pretty much restored.”56

Before Christmas of 1892, after several decades of declining health, plus the onset of tuberculosis, Jacob Lemke died. His daughter, Mrs. Maria Derksen, reported: “My dear father Jacob Lemke, also from Gruenfeld, who had been very ill for 20 years, died on November 30th at the age of 55 years, 5 months, 14 days, after an eight-week serious illness. . . . Mother is still quite sprightly. Her children, the Kornelius Rempels, now live with her. Mother is disposed to continue the farm with the children: she still has a daughter at home and a foster son of 13 years.”57 At the time of Jacob’s passing, it seems that Maria was still living at Neuenburg. The Rundschau letters do not indicate whether she was able to attend her son’s winter funeral.

Sometime after her son’s death – and well before June of 1903 – Maria and Franz moved back to Gruenfeld, as did their bereaved daughter-in-law, her children, and her second husband, Dietrich Rempel (b. August 4, 1823). 58 This return to Gruenfeld appears to have been a final move for Maria and Franz. Many of their grandchildren were settled at this area, and so they would have been well positioned to witness and support the family’s growth.

The Years That Follow

In their beloved corner of imperial Russia, Franz and Maria (Kehler) Janzen reached their golden age and became the honoured oldest couple in the village. In about 1898, the couple celebrated their silver anniversary. They had taken great joy in the proceedings.59 Their grandson-in-law Heinrich P. Peters said that around the time of the anniversary, in what might have been a new spirit of self-reflection, Maria and her husband built in Gruenfeld a charitable institution called the Ebenezer.60

Significant changes to Maria’s family’s structure occurred during the final two decades of the nineteenth century. The grandchildren were getting baptized, marrying, and developing households. Maria’s grandson Johann Johann Lemke, for instance, moved to Orenburg to help settle Chortitza #1.61 While the younger generation emerged, the family bade farewell to Maria’s brother, Michael Kehler, who passed away in May of 1896, and to sister Helena Kehler Thiessen, who died on March 25, 1900.62

As the family grew and changed, so did their beloved village. Starting about 1906, the colony experienced an economic boom, driven by migration to Siberia.63 Maria’s grandson-in-law, Kornelius Peter Rempel, described Gruenfeld’s appearance: “Our former hometown, with about 650 Einwohner [renters], was beautiful at the time when in the dear fatherland there was still a desire for peace. The large [Froese] factory, 2 steam mills at the end of the village, the railway line, all the beautiful orchards, lent a romantic impression.”64 Indeed, extant village photographs show a broad street with lovely homes cradled by fences and shielded by trees. A new school had been built back in the 1890s; by 1908, over a hundred children were enrolled. Dotting the landscape were two windmills. One prominent local structure was the Froese factory for agricultural machinery. The railway line was crowned with a grove of trees. Somewhere in this pretty village, troupes began performing Low German plays written by Jacob H. Janzen.

In a significant spiritual shift for the colony, the Mennonite Brethren church reached Steinfeld at the end of the nineteenth century.65 More than half of the Steinfelders are said to have joined the new church through immersion rebaptism; it is not hard to imagine the tension this must have caused in the area. Jakob Redekopp wrote about how the colony’s young people took part in Bible studies and prayer hours.66 Regarding the older generation, Redekopp added: “They probably didn’t want to slip off their track anymore.” Perhaps the Janzens were among those who were influenced by this spiritual awakening and this manifested in their building of Ebenezer. We do know it was announced in early 1908 that Gruenfeld was finally to receive its own church building after more than a quarter-century of existence.67

Living in “this peaceful village,” Maria kept herself busy, even into her eighties and nineties.68 As late as the summer of 1903, she continued her everyday farm routine, both indoors and on the yard. Maria Martens Peters, in correspondence published in June 1903, stated that her grandmother “is still alive, works, cooks, and runs her small chicken farm every day. She is already more than 88-and-a-half years old.”69 To sign off, Mrs. Peters referenced 1 Samuel 7:12: “Then Samuel took a stone, and set it between Mizpeh and Shen, and called the name of it Ebenezer, saying, Hitherto hath the LORD helped us.”

Interrupting the pastoral scenes of Maria’s golden years was a particularly tragic period late in the summer of 1903. On August 27, her granddaughter Elisabeth, daughter of Johann Lemke, died of a hemorrhage.70 Around the time that the young woman was laid to rest, a wind caught sparks from a locomotive and tossed them onto a straw roof.71 According to Sara DeFehr, “the factory sirens whistled incessantly,” and the train hauled water from the Dolginzovo, nineteen kilometres away, to extinguish the blaze.72 Grandson Jacob David Derksen (b. June 18, 1884) reported on the devastation: “A fire broke out in the house of one of the Anwohner [cottagers], and . . . 22 homes were burned, including our things and all the grain. Except for cattle and wagons, everything was turned to ashes. And so we were forced to buy again everything that was useful and necessary.”73 As the Johann Lemkes grieved the loss of their daughter, who had been ill since the spring, their yard was hit hard by the conflagration: they lost their Nebenscheune (barn), chaff, straw, and farm implements. Fire remained a perennial threat in the Schlachtin colony. Maria and Franz’s home, in fact, burned down twice during their marriage. Early September of 1903 was the date of the first fire. At this time, the old grandparents gave up their own yard and moved in with their children, the Jacob Martenses, “in the little house on the farm.”74

The life story of Maria Kehler Lemke Janzen will continue in the next issue of Preservings.

- I would like to thank Glenn H. Penner, Conrad Stoesz, and my parents for their help with this article. ↩︎

- Peter Rempel, Mennonite Migration to Russia, 1788–1828, ed. Alfred H. Redekopp and Richard D. Thiessen (Winnipeg: Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society, 2000), 33; Benjamin Heinrich Unruh, Die niederländisch-niederdeutschen Hintergründe der mennonitischen, Ostwanderungen im 16., 18. und 19. Jahrhundert (Karlsruhe: self-pub., 1955), 241, 248. ↩︎

- “Chortitza Mennonite Settlement Census for 1 September 1801,” available at Mennonite Genealogy (website, hereafter cited as MGW); “Chortitza Mennonite Settlement Census for October 1816,” MGW; Rempel, Mennonite Migration, 12; Unruh, Niederländisch-niederdeutschen Hintergründe 242, 246, 258. Unless otherwise specified, all references to sources on the Mennonite Genealogy website are linked from the Russia index page, at https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/russia/. ↩︎

- “Funds Loaned to Mennonite Settlers in the Chortitza Settlement: 1788-1793,” MGW; “Chortitza Colony Vital Records: 1801-1813,” MGW. ↩︎

- Rempel, Mennonite Migration, 12. ↩︎

- “Chortitza Colony Settlement Census lists for Nov. 1815, May 1816, and Oct. 1816,” MGW; Henry Schapansky, Mennonite Migrations (and the Old Colony) (self-pub., 2006), 709; Mennonitische Rundschau (hereafter cited as MR), Jan. 20, 1904, 9; MR, Feb. 10, 1904, 4–5. ↩︎

- MR, Mar. 8, 1905, 10. ↩︎

- See entry #83 of “Register of Persons Living Outside the Chortitza Colony in 1852,” MGW; Schapansky, Migrations, 396. ↩︎

- “Chortitza Mennonite Settlement Vital Records: 1809-1812,” MGW. ↩︎

- “Chortitza Mennonite Settlement Census for November 1811,” MGW; Unruh, Niederländisch-niederdeutschen Hintergründe, 278. Foster father Nickel was a weaver. ↩︎

- Chortitza Family Registers, vol. 1, 238, MGW. ↩︎

- “Register of Persons Living Outside the Chortitza Colony in 1852”; Schoenhorst Church Register, 137 (index at MGW); Chortitza Family Registers, 1:238; Berlin Document Center, A3342-EWZ50-E081/0568. ↩︎

- “Register of Persons Living Outside the Chortitza Colony in 1852,” MGW. ↩︎

- “Register of Persons Living Outside the Chortitza Colony in 1859,” MGW. Michael Kehler (age 40) is listed with wife Helena (age 20) and children. There is a Johann Lemke listed as an Anwohner in 1863 at Kronsweide in “Chortitza Colony Village Lists for 1863,” MGW. ↩︎

- “Register of Persons Living Outside the Chortitza Colony in 1852,” MGW; West Abbotsford Mennonite Church Records (per the Genealogical Registry and Database of Mennonite Ancestry [GRanDMA]). ↩︎

- MR, May 27, 1891, 3; Feb. 7, 1894, 1; Jan. 17, 1906, 2; “Register of Persons Living Outside the Chortitza Colony in 1852”; MR, Jan. 17, 1906, 2; MR, Apr. 12, 1911, 10; MR, Jan. 28, 1914, 7–8. ↩︎

- “Register of Persons Living Outside the Chortitza Colony in 1852”; Schoenhorst Church Register, 137; MR, Jan. 28, 1914, 7–8; MR, July 14, 1965, 5; various other references in the family’s GRanDMA profiles. ↩︎

- MR, Apr. 13, 1904, 9; Apr. 12, 1911, 10. ↩︎

- Ibid.; MR, Dec. 18, 1912, 9, 12. ↩︎

- “Register of Persons Living Outside the Chortitza Colony in 1852”; Chortitza Family Registers, 1:238; Berlin Document Center A3342-EWZ50-E081/0568. He may have owned a brick factory at Neuenburg, as indicated on Viktor Petkau and Willi Vogt’s Ziegelfabrik list, “Ziegelwerke der Mennoniten in Russland,” Mennonitische Geschichte und Ahnenforschung (website), https://chortitza.org/Buch/ziegel.php. ↩︎

- Jakob Martens, So wie es war: Erinnerungen eines Verbannten (privately published, 1963); Berlin Document Center A3342-EWZ50-B046/2870. Currently, J. H. Martens is labelled in GRanDMA as #339145 and #1428054. “Register of Persons Living Outside the Chortitza Colony in 1852”; MR, Jan. 28, 1914, 7–8; Berlin Document Center A3342-EWZ50-F032/0852; “Mennonite Passenger Lists for Refugee Transport to Paraguay in 1930,” MGW, https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/latin/paraguay1930.htm. ↩︎

- MR, Feb. 16, 1910, 13. ↩︎

- See their respective GRanDMA profiles. ↩︎

- MR, Feb. 16, 1910, 13. ↩︎

- MR, Apr. 6, 1904, 5. In later letters, Janzen and other Frindschaft mention slightly different dates for his birthday while that of his wife remains consistent. ↩︎

- See family #3 on the list “Mennonites from Kronsgarten in the Chortitza Colony Who Requested Transfer to the Chortitza Volost (May 1836),” MGW. ↩︎

- John Friesen, Against the Wind: The Story of Four Mennonite Villages (Gnadental, Grünfeld, Neu-Chortitza and Steinfeld) in Southern Ukraine, 1872–1943 (Winnipeg: Henderson Books, 1994), 21. ↩︎

- See Epp’s diary entry of May 22, 1875. Harvey L. Dyck, trans. and ed., A Mennonite in Russia: The Diaries of Jacob D. Epp, 1851–1880 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 391. ↩︎

- MR, July 10, 1907, 9–10. ↩︎

- MR, Jan. 20, 1892, 2. ↩︎

- MR, Feb. 6, 1889, 1. It is possible that Maria Kehler had already moved to Schlachtin with her first husband, as a certain Lemke is known to have been an original settler at Gruenfeld, according to Friesen, Against the Wind, 26. ↩︎

- Friesen, Against the Wind, 26. ↩︎

- Al Reimer, Syd Reimer, and Glen Kehler, The Berliner Kehler Clan: A History in Portraits (Kelowna, BC: Rosetta Projects, 2009), 11. ↩︎

- MR, May 14, 1924, 7–8. ↩︎

- MR, May 5, 1909, 7. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- See Jakob Redekopp, Es war die Heimat: Baratow-Schlachtjin (Curitiba, Brazil: Tipografia Santa Cruz, 1966), ↩︎

- Friesen, Against the Wind, 43–46. ↩︎

- Ibid.; Redekopp, Es war die Heimat, 32; Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, s.v. “Neu-Chortitza (Baratov Settlement, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, Ukraine).” ↩︎

- Sara Heinrich DeFehr, ed., Im Wandel der Jahre (Winnipeg: Regehr’s Printing, 1975), 123. ↩︎

- Likely Anna Reimer Siemens, GRanDMA #163908. DeFehr, Im Wandel der Jahre, 122. ↩︎

- Walter Wiebe, “Dass sich solches niemals wiederholt: 130 Jahre Grünfeld,” Mennonitische Geschichte und Ahnenforschung, https://chortitza.org/WWiebe.htm. ↩︎

- Friesen, Against the Wind, 27. ↩︎

- Redekopp, Es war die Heimat, 24. ↩︎

- See, for example, Reimer, Reimer, and Kehler, The Berliner Kehler Clan, and Gerhard K. Kehler’s life writing, involving a catastrophic fire and the difficulty of making do on fire insurance money, Preservings, no. 8, part 1 (1996): 41–42. ↩︎

- Wiebe, “130 Jahre Grünfeld.” ↩︎

- MR, Mar. 2, 1887, 1. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- MR, Feb. 6, 1889, 1. ↩︎

- MR, Mar. 6, 1889, 3. ↩︎

- MR, Feb. 6, 1889, 1. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- MR, June 12, 1889, 1. ↩︎

- MR, June 18, 1890, 1. ↩︎

- MR, Dec. 24, 1890, 1. In the same letter, Lemke notes the recent death of esteemed local minister Jacob Epp. ↩︎

- MR, Jan. 20, 1892, 2. ↩︎

- MR, Mar. 15, 1893, 1. The identity of the foster son is not known. ↩︎

- MR, June 10, 1903, 9. ↩︎

- MR, July 10, 1907, 9–10. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Chortitza Nr.1: Erste Ansiedler im Jahr 1894,” Sipai Kanzerovka Droi (website), http://sepai-kanzerovka.de/ahnenforschung/chortitza-nr-1. ↩︎

- The death dates for brother Peter and for the sister who married a Blatz are not known except that both siblings predeceased Maria. ↩︎

- Redekopp, Es war die Heimat, 32. ↩︎

- MR, Apr. 30, 1924, 11. ↩︎

- Redekopp, Es war die Heimat, 21. ↩︎

- Ibid., 23. See MR, Aug. 26, 1953, 11. ↩︎

- MR, Apr. 1, 1908, 13. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- MR, June 10, 1903, 9. ↩︎

- MR, Apr. 13, 1904, 9; May 18, 1904, 4–5. ↩︎

- Friesen, Against the Wind, 66; Redekopp, Es war die Heimat, 30. ↩︎

- Redekopp, Es war die Heimat, 159. ↩︎

- MR, Apr. 12, 1905, 5. ↩︎

- MR, Jan. 20, 1904, 9. ↩︎