A Mennonite Travelogue: Martin B. Fast in South Russia

On his 1908 tour of the Mennonite colonies in South Russia (present-day Ukraine), Martin B. Fast, then the editor of Die Mennonitsche Rundschau, visited family and friends in the Molotschna colony and made new acquaintances in Crimea. He recorded his travels in the book Reisebericht und Kurze Geschichte der Mennoniten (A travelogue and brief history of the Mennonites), which has been recently translated.1

During the first half of this trip, covered in the last issue of Preservings, Fast visited many villages in the Molotschna colony. A few weeks into the trip, he boarded a train bound for Berdyansk, on the Sea of Azov. In this picturesque city, Molotschna Mennonites shipped their wheat and other produce to market. Beginning in the 1840s, some Mennonites moved to this city and settled in what was known as the German Quarter.2 One of these Mennonites was Cornelius Jansen, a prominent grain merchant, who lived in the city until 1873, when he left with his family for North America. His young son, Peter, purchased a large property in Nebraska, raised sheep, and later founded the town of Jansen. Fast, who was also a young man when his family arrived in the United States in 1877, had lived near the sheep ranch and had come to know Peter.

While in Berdyansk, Fast visited another family of grain merchants, the Sudermans. Fast wrote that as a young boy he had seen their yard and their large wheat warehouse while delivering wheat with his father. He brought them greetings from his “friend and neighbour Peter Jansen” and was warmly welcomed inside for coffee.

He also visited a colleague, Heinrich Abram Ediger, co-editor of the Mennonite periodical Der Botschafter. Later Fast visited the bazaar, as he had been looking forward to tasting the little prianiki (Pfefferkuchen). As it turned out, the market no longer sold gingerbread cookies and Fast had to purchase “something similar” to relive his childhood memory.

To Sevastopol

On a June evening, he boarded a steamer headed for Kerch. There he transferred to a “beautiful ship” to travel along the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula to Sevastopol. Fast informed his readers that “Crimea is a wonderful bit of land, which plays an important role in world history. . . . There is probably no spot on earth on which more blood has been shed in order to possess it than Crimea – perhaps Palestine.”

Early in the morning the steamer docked in Yalta. “Yes, Yalta – what Russian child has not heard about the splendours of Yalta and Livadia?” He described the view as he left the ship and walked up a nearby hill: “The buildings lie hidden under high trees. On the highest point stood a beautiful little church.” Fast entered and listened to the chanting of the priests. Soon the ship sounded its signal for departure and they passed slowly by Livadia. “The Russian imperial family has its beautiful palace here. When in St. Petersburg the ground is frozen solid, the roses bloom here.”

One thing impressed him. “From Yalta to far past Livadia, you see numerous sentry booths; many of them lie hidden in the thickets, others stand out in the open. There the guards in the grey cloaks of the Tsar walk back and forth and see to it that the ‘Little Father’ and his large entourage can live in safety.”

Sevastopol finally came into view. Fast wrote, “The Black Sea, the bay, the inlets and the harbour all lie in a remarkable location and it seems impossible that an enemy could ever storm and conquer this city.” He disembarked and hired a carriage to take him up the hill to visit P. M. Friesen, who lived among “the Baptists.” The carriage stopped at a stately house with a small sign on the door: “Petro Martinovich Friesen.”

P. M. Friesen had left Molotschna colony after teaching and serving as principal in the secondary school (Zentralschule) in Halbstadt. He was also active in the Mennonite Brethren Church. In 1884 he was ordained as a minister and he later wrote the church’s confession of faith. Fluent in the Russian language, he had moved to Sevastopol to serve in a Russian evangelical church. His home became a gathering place for Mennonite students.3

Fast had never met P. M. and Susanna Friesen, but he had seen photographs of them and recognized these “dear people” immediately. As he recalled, “Their hospitality made me feel very comfortable in their home. I observed their activities, saw the converted Russians and how they all sought advice from ‘Petrushka’ [the diminutive of Peter].” He also saw how the two Russian congregations requested and valued Friesen’s advice on the conduct of holy communion and other religious topics.

Fast and his host shared some of their experiences and had coffee and cake under the shady arbour. Later that year, Fast wrote in the Rundschau that Friesen was “the mainspring of the evangelical movement among the Russians searching for salvation.” P. M. Friesen took issue with this characterization. Fast addressed this in his travelogue: “When Br. Friesen read this in the Rundschau, he did not believe this to be correct and asked me to withdraw the statement. I am doing that, because, as I am well aware, as he writes, the Holy Ghost is the mainspring of the movement. However, in the sense in which I wrote it and in those circumstances, Br. Friesen can be considered the instrument in God’s hand (that is, mainspring). Especially in the organization, the founding, and the support of Russian congregations, he has contributed a great deal through his efforts to the good of the cause.”

Historic Sites

After a good night’s rest, Fast and his guide, a Miss Esau, hired a cab to see the sights of the world-famous city. They drove out to Chersonesus and then to the Soldiers’ Museum. Fast was affected by what he saw: “Here you see the horrible consequences of the Crimean War. Generals, officers, and ordinary soldiers in life-size wax and bronze figures. The old lances, rifles, and sabres told a tragic story; even the axe of the poor Ratnik [warrior] can be seen there. . . . I had to think over and over again – how horrible war is! The question oppresses me: ‘Lord, how long must we wait until the time comes when people don’t learn war any more and no people raise the sword against others?’”

The next day, Olga Friesen, P. M.’s daughter, took him to visit the cemetery. Fast commented: “There lie buried the poor soldiers who fell in the Crimean War. On this hill, covered with bushes, you see graves with 100 and 1,000 in one grave!” Among the many graves was that of General Eduard von Totleben, whom Fast vividly recalled from his visit to the colonies in 1874. “A very expensive statue has been set on his grave. He talked to our people to persuade them to stay in the country and accept military obligation. He maintained at the time that, although freedom of conscience did exist in America, eventually Mennonites in America would be forced to serve in the military.”

They also saw the Siege of Sevastopol panorama created by artist Franz Roubaud. It had been unveiled in 1905, three years before Fast’s visit.4 In the panorama he tried to orient himself and find the spot on which “our fathers and grandfathers stood with their wagons in the ‘time of podvod’ [Russian for supply].”

To Spat

After they returned to the Friesen home, Fast bade his hosts farewell and then took the train to Spat. This town, established in 1881, was new to him. Near a recently constructed railway line, Spat had developed into the largest Mennonite village in Crimea.5 Fast visited the Langeman machine factory, which employed sixty-three people. They had just finished building eighty-one threshing machines. “The ones with 10 horsepower cost 1,200 rubles. These threshing machines, powered by horses, are very simply constructed. Most farmers have one standing in or near their large barn.”

He reported that Spat was a beautiful village with a wide street. “The Mennonites have built a secondary school. This school is nicely equipped and cost 15,000 rubles. Two desiatiny of land [about five acres] and three residences for the teachers belong to the school. . . . The seating for the students was already Americanized – two students per seat.” A meeting was set for Wednesday morning. “Br. Huebert made the opening and then I was permitted to speak to the attentive listeners.”

Later, he boarded a train bound for Melitopol, an important trade centre just south of Molotschna. Mennonite families had formed a small community around 1840 and established a Mennonite church supported by local estate owners.6 As Fast recalled, “The carriage driver knew where the nemtsi [Germans] lived and took me there.” It was a considerable distance from the train station to the German street, but they finally arrived at the spacious house of J. Neufeld, next to a large steam-driven mill. Fast asked the carriage driver to wait and went up to the door.

He learned that Neufeld’s wife had gone with Abr. Klaassen and his family to their estate in Crimea. Klaassen owned a steam-driven mill that ground “1,500 bushels every 24 hours.” At the time, “flour cost 5 rubles, 25 kopecks for 100 pounds. They produce eight different kinds of flour.” Although Neufeld was alone, he hosted Fast “graciously.” After coffee, Neufeld took him to the park. As Fast wrote, “It is really beautiful; I had hardly expected anything like it. The leading men of the city, which included my host, have built an extra fine bathhouse there. An artificial well fills a basin built of cement with clear water. We played around to our hearts’ content in the water, which was just warm enough.”

To Alt Berdyansk

Fast stayed overnight at the Neufelds’, and the next morning Neufeld’s friend, Brother Enns, picked them up in a carriage driven by his Russian coachman. They made their way to the forestry project, set up in the 1870s to provide an alternative to military service for young Mennonite men. The men grew trees and planted them in open land throughout South Russia. “Every year many improved trees both for fruit and for forests were given free of charge to the Russians living in the neighborhood to create in them a desire to plant orchards and woods.”7

The visitors were welcomed by Wilh. Loewen, preacher and agriculturist at Alt Berdyansk, and shown the buildings and the equipment. “The young men were divided into groups and were expected to take care of themselves. I saw how they cooked Pflaumenmus [plum butter], baked ‘Schnetki’ [biscuits], and made themselves useful with the housework.”

From there they drove through a former model village laid out years before by Johann Cornies. According to Fast, “It was to serve as a pattern and example for the Russians. The beautiful houses, which were built after a German plan, with metal roofs, etc., showed how prosperous the peasants had become.” Leaving the village, Fast saw the large stone marking the border with Molotschna, which Cornies had set up a hundred years before. He commented: “We found ourselves once more on German soil.”

To Ohrloff

The next Sunday morning, Fast attended a service at the Mennonite church in Ohrloff. His father had grown up in this church. “As a young boy I had been to church in Ohrloff twice and when we drove into the yard I looked at the old building with a certain reverence. Here my father and grandfather had often kneeled in reverence to pray. Here more than 1,000 young people had promised God on their knees before many witnesses to walk a new life from that moment on!” At the church, Fast discovered that “dear Elder Abr. Goerz had driven to Neukirch to administer holy communion. Br. Joh. Wiens of Rosenort gave the opening and then I was permitted to speak to the congregation. I felt myself richly blessed.”

The next day, he went to Halbstadt with Wilh. Janzen to attend a Bible study conference. Fast commented, “For me, it was interesting and stimulating to greet and listen to men of whom I had often heard or read.” That evening he drove to Rueckenau to visit Brother and Sister Pet. Braun, who lived on a farm previously owned by Franz Martens. Martens, who had bought the farm from Joh. Dick, had torn down all the old buildings and put up modern ones. After Martens died, the Brauns bought the place for 20,050 rubles. Fast learned that “there was general astonishment” over this sale price; “however, today 25,000 rubles for a farm in Rueckenau is quite common.”

He also visited Brother and Sister Heinrich Martens, and had a “short but beautiful devotion.” Sister Martens had just recently made a trip to Crimea. “All too soon the time came that I had to leave for Tiegerweide for the funeral of a cousin, Frau Dick (nee Katharina Fast).” Brother Martens drove him to Tiegerweide, the village where Fast was born in 1857. His uncle had cleaned out the barn for the funeral. Brother Jakob Wiens gave the funeral sermon. Then the coffin was put onto a wagon and the horses were led by two men to the cemetery. “Three of my little brothers and sisters also lie buried there.” After coffee at the home of the deceased, Fast spoke to those gathered.

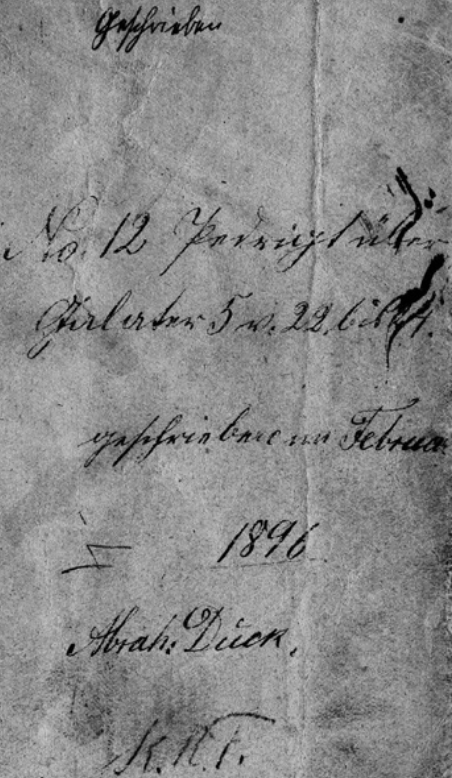

To Schoensee

The next morning Jul. Barkman and Korn. Boschman drove him almost due north to Schoensee, which in 1908 was a tree-filled village on the south bank of the Tokmak River.8 Fast needed to settle a small inheritance for someone in Kansas and was welcomed very cordially by the Dicks. They walked to the local church, which was a small, plain, wood-sided structure built in 1831 in the Prussian Bethaus tradition.9 Fast found this old building to be fascinating. The year after his visit, it was replaced by a large ornate building.

They also walked over to the cemetery, high up on the “other side of the sandpit,” then returned to his hosts. His visit ended in typical Mennonite fashion, as some neighbours came over for lunch, and after a nap, a large carriage was harnessed and the Dicks took Fast to Halbstadt.

In Halbstadt, he visited the Walls. Fast had some physical concerns, and early the next morning, Brother Wall sent Fast to his cousin, Abr. Wall, a well-known doctor in Halbstadt. When they arrived, they saw vehicles lined up, filled with men, women, and children who had spent the night waiting with their ailments. As Fast recalled, “I had only a short time with Dr. Wall, but I was very happy to get to know him. He is a brother of the dear Elder C. M. Wall of Henderson, Nebraska. He gave me some brotherly advice.”

To Schoenfeld

Saturday morning, Fast went to the station in Prischib; he planned to visit Mennonites living to the north of Molotschna, in the settlement of Schoenfeld. Because of heavy rains, the train was late and it was nearly evening by the time he arrived in Sofievka, a town with a small Mennonite community.10 Brother Enns from Tiegenhof sent his son to pick Fast up. He was given a hearty welcome and “felt right at home.” Sunday morning, before they left for church in nearby Rosenhof, they took a walk in a well-kept garden.

The Rosenhof church, built in 1880, was attended by people who lived on neighbouring estates.11 At the church, Fast was greeted by Isaak Thiessen and Rev. Epp and was asked to speak to the congregation, which included many of the wealthy landowners. From the pulpit he said, “May the loving God bless our fellowship together.”

After his time in the Schoenfeld settlement, Thiessen and his son drove Fast towards Aleksandrovsk, one of seven city-fortresses built in 1770, after the war with Turkey, to protect the southern territories.12 Fast stopped at the home of Jul. Siemens, the mayor of Schoenwiese, and had lunch.

On the Dnieper

After lunch, Siemens sent Fast down to the Dnieper River landing where he boarded a small steamship bound upstream for Chortitza. On the steamship, his thoughts turned to history: “At the place where the river divides, I was shown a huge rock in the water, where Empress Katharina [Catherine II], at the time our forefathers settled on the Dnieper 122 years ago, stopped with her entourage and had tea.”

The slowness of Fast’s trip caused him to become restless. He was saved when a “dear man came up and spoke to me in a friendly fashion. It was David Kroeger, the man who makes the wall clocks with the long pendulum – the old-fashioned way.” By the time they had arrived at Chortitza, Kroger had invited him to his house in Rosenthal.

Fast laughed after seeing the winding streets of the village. As he wrote, “I don’t want to insult anyone, but they certainly didn’t have a Cornies around to lay out the village plan when they built these houses.” He toured Kroeger’s clock factory, located in his yard, and admired the clocks: “The clocks were really beautiful. They were also starting to manufacture machines.” He was very tempted to purchase one and take it home, but didn’t know how much duty “Uncle Sam” would make him pay at customs.

To Chortitza

In the morning, Fast went to look up his agent, H. Borm, who owned a spacious bookstore. “I was pleased to get to know him personally. We have done a lot of business together in the last five years.” Fast then went to the house where he thought the famous Privilegium had been preserved “as a little gem.” He learned, however, that the document was now stored at the courthouse. In the courthouse, Fast reflected on the significance of this document: “Of course, it has lost its value since 1870; that is, the assured privileges, which were supposed to last forever, have been withdrawn by the Tsar. However, it is a good thing that one can see the document now and then, to remind us of that wonderful time.” He was permitted to take it to another room and look at it all by himself. “It is really a splendid specimen for the time in which it was prepared. I had been told how long the authorized representatives had to wait until it was ready – almost two years!” Fast continued, “Of course I had read the contents often as a young boy and had copied it for myself and for others. . . . I read it and when I got to Point 5 and read it, I had to give an involuntary sigh. Oh, my God! Point 5 reads: ‘On the lands belonging to the Mennonites we forbid the construction by outsiders of taverns and bars that serve brandy. We also forbid the sale of brandy and the ownership of taverns without the consent of the Mennonites.’ What happened then is not that an outside evil slithered its way into the villages of the Mennonites, but rather that the Mennonites brought in unrefined spirits on their own, then later built distilleries, and with that not only violated the indirect suggestion of the highest authority but acted against their own well-being. And of course the consequences are not wanting.”

A cemetery

Fast and a companion then went to the old cemetery in Chortitza where they saw some of the oldest Mennonite graves in Russia. He reflected: “There lie buried many of the old heroes, who did so much and put up with so much in order to bring our forefathers to this land of freedom – to Russia.”

They also visited a large memorial statue. Fast commented: “It is beautiful and a silent witness that reminds us of the past.” The statue, a marble obelisk, surrounded by a white iron fence, commemorated Johann Bartsch, one of the two delegates who arranged for the Mennonite exodus from Prussia to South Russia. The first to arrive in Chortitza were unhappy with the land and laid the blame on these delegates. Both were excommunicated from the church, although Bartsch was later reinstated.13 Fast reflected that Bartsch was both beloved and honoured – hated and vilified, “as happens to men who have sacrificed more than the average person, which still happens today.” Fast did not mention Hoeppner, the other delegate.

To Memrik Colony

Next Fast headed into an unfamiliar territory, the Memrik colony, which had been established in 1884. The land, purchased from two noblemen, was located about two hundred kilometres east of the Chortitza colony. “The land was then mostly unbroken prairie, but of exceptional quality.”14 When Fast arrived at the railroad station in Zhelannoe, he saw a carriage belonging to a Heinrichs who owned a steam-driven mill in nearby Kotlyarevka. He persuaded the Russian coachman to take him along. Fast was going to see his cousin, Martin Barkman, son of Kornelius Barkman, the “last of my grandfather Martin Barkman’s nine children.”

The next morning he drove to another village, Alexanderhof, established in 1885, to visit more cousins. That evening they went to Karpovka to visit Gerhard Wiens, who was half American and had rented property at 40 rubles per desiatina (2.2 acres). The following day, he was invited to a gathering of brethren in Kotlyarevka. The Mennonite Brethren had constructed a church there ten years before. Isaak Fast, an elder, received him “heartily” and Fast spoke to the group. Afterwards, a number of new converts were tested about their beliefs.

After bidding farewell, the Barkmans took him to the train station in Zhelannoe and he left for Gulai’pole to visit his father’s youngest sister, Justina Fast Nachtigall. Fast recognized her immediately and learned that his aunt had a foster daughter who was married and had “several lively children.” Early the next morning he was back at the station, headed for Grossweide. Through Elder D. Nickel, notices were sent out that the editor of the Rundschau would be preaching at the school that afternoon. They “were richly blessed in the gathering.”

To Tiegerweide

Fast made his way to Tiegerweide, where he had many conversations and visits: “I was welcomed everywhere. Now and then I was given a token of my visit and packed them in my suitcase.” A farewell event was scheduled for Sunday morning. When Fast arrived at the school, he was “quite astonished to find the whole village congregation – with few exceptions – gathered there.” For the final time, Fast spoke to “the dear people of Tiegerweide. My wish is that our being together may have been a blessing and remain such until we see each other again.”

At noon, they went to his uncle’s house. Several friends, from Kleefeld and Alexanderkrone, from Prangenau and Alexanderwohl, plus quite a few neighbours, gathered for the noon meal. “The time seemed too short to say all that we wanted to – our heart was so full and so moved.”

Fast began his journey home by taking a train south to Sevastopol, where he again went to P. M. Friesen’s home. “I felt very much at home with the Friesens. Peter had chosen a prominent place for his home and the view from the balcony is really beautiful. Sister Friesen, in motherly fashion, put all my laundry in good order.” After bidding them farewell, he was driven to the harbour, where he boarded a steamer for Odessa.

In Odessa, he bought a train ticket for Berlin and then sailed from Bremen. Back in Elkhart, he greeted his family and returned to his desk at the Rundschau, before travelling to several Mennonite communities to attend conferences and deliver the results of the commissions and messages he had received from Mennonites in South Russia.

- Martin B. Fast’s Reisebericht und kurze Geschichte der Mennoniten (Scottdale, PA, 1909), was translated by George Reimer, of Minneapolis. His parents escaped from the Soviet Union through China and immigrated to the United States shortly before his birth in 1931. For over three decades he taught German and Russian to high school students. He died unexpectedly in late 2019.

- Rudy P. Friesen with Edith E. Friesen, Building on the Past: Mennonite Architecture, Landscape and Settlements in Russia/Ukraine (Winnipeg: Raduga Publications, 2004), 680.

- Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO), s.v. “Friesen, Peter Martin (1849-1914),” by H. P. Toews and Cornelius Krahn.

- Wikipedia, s.v. “Franz Roubaud,” last modified Mar. 23, 2019.

- Friesen, Building on the Past, 410.

- Ibid., 697–98.

- GAMEO, s.v. “Forsteidienst,” by Abraham Braun, Th. Block, and Lawrence Klippenstein.

- Friesen, Building on the Past, 364.

- Ibid., 364.

- Ibid., 708.

- Ibid., 466.

- Ibid., 666.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 539.

Also In this Issue

Proof in Material Culture: Mennonite Alcohol Consumption

Liquor Licenses: Winkler of the 1890s

Objections to Alcohol: The Rise and Fall of Temperance in Winkler

Mennonite Nectar: Alcohol Production in the Vistula Delta

Alcohol Production: In the Chortitza and Bergthal Colonies

Alcohol & Abstinence: Mennonites in South Russia

Addiction & Recovery: Mennonites in Mexico & Bolivia

The Political Life of Jacob Penner

Admonishment & Joy Deferred: Four Sermons of Aeltester Abraham L. Dueck

Whisky Sales and Hotel Tales of the Mennonite West Reserve, 1873-1916

Menno-Nightcaps: Cocktails Inspired by that Odd Ethno-Religious Group You Keep Mistaking for the Amish, Quakers or Mormons