The Political Life of Jacob Penner

In the last issue of Preservings, I explored how Jacob P. Penner, a Russian Mennonite with Mennonite Brethren and Kleine Gemeinde family roots, immigrated to Canada, established a family, and became active politically as a communist. These years must have been a blur for Penner. He was roundly defeated in a 1921 run for federal office, and again in 1927 for provincial office. In 1931 and 1932 he ran for mayor and was again both times defeated.

During his 1931 run, Penner and two other communist candidates, running for alderman and for the school board, released a platform that would fight for cash relief for single and married unemployed workers, regardless of residential or other qualifications. In a promise extending well beyond municipal jurisdiction, Penner declared that the provincial and federal governments would cover the costs of his unemployment benefits scheme. The group would also work for a minimum wage of twenty-five dollars per week, a seven-hour workday, a five-day work week, and the right to belong to the union of their choice. Universal free healthcare and free education from primary school through university were additional pillars of the platform.1

Elected to Serve

In 1932, Penner also took a run at a seat in the provincial legislature, picking up 1,106 votes in his losing effort. In 1933, he was tapped as a communist candidate when Leslie Morris was stricken from the ballot on a technicality. Penner won and assumed his seat on city council on January 2, 1934.2 Upon being elected to office, Penner quit his job as a bookkeeper at the Workers’ and Farmers’ Cooperative and became a full-time alderman. He received a salary of thirty dollars a month. His job at the co-op had been paying twenty-five dollars a week. As a married father of five, he was now making less than he had earned as a single adult in his first teaching job in Altona almost thirty years earlier. Most of the other elected aldermen had commercial interests or jobs and continued with their paid work outside council chambers. Penner, however, dedicated his complete attention to the needs of his constituents. As he told his wife, Rose, “I was elected to serve the people and I cannot do that part-time!”3

As a city councillor Penner was frequently called upon by constituents to assist in getting access to relief aid. This sometimes led to comical situations, as his son recalled: “When, shortly after Dad’s election, we got our first phone and his name appeared in the 1934 phone directory, there was only one other Penner listed, and he was also Jacob Penner. This other Jacob Penner, who lived just a short distance away on Inkster Boulevard, was a chimney sweep who could not understand why he was so constantly being asked for help with relief problems! (And, of course, not infrequently, we had to turn down requests to have chimneys swept.)”4

In his early years as alderman, Penner won the right for men on relief to picket. In 1934, when the mayor was absent from a meeting, Penner cast the deciding vote on a motion for a 20 percent increase of the food allowance in the schedule of relief rates. Mayor Ralph Webb – a long-time rival of Penner – used his chairman’s vote at a later meeting to cause a review of the increase. Eventually a compromise was reached for a 9 percent increase.5

Penner’s German-Russian background was free license for his political opponents to label him as a radical, a revolutionary, a Bolshevist, and more. In Winnipeg, these identities were dangerous. According to Stefan Epp-Koop, the 1907 Immigration Act allowed local municipalities “to request the deportation of any immigrant who became a public charge.” In Winnipeg, people who were considered “political radicals” also were sometimes deported. Deportations happened so frequently that some European consuls “inquired into why so many of their citizens were being deported from Winnipeg.”6

In his new office as alderman Penner worked with the Independent Labour Party to end the practice of deporting the unemployed. Penner joined aldermen Thomas Flye, Morris Gray, and John Blumberg in raising the issue at city council, and under their pressure it was revealed that the city was using its deportation powers excessively. Other aldermen began to question the practice, and those who had previously supported automatic deportation for economic reasons became convinced it was an “apparent betrayal of British principles of fair play and justice.” In January 1934, the council decided to cease reporting public charge cases due to unemployment to the Department of Immigration.7

Penner also pushed to relieve the plight of workers. During a lengthy and violent strike at the Western Packing Company in 1934, Penner condemned sweatshop conditions at the plant. On April 4, 1934, Penner and communist school trustee Andrew Bileski addressed two thousand Winnipeg citizens who gathered at the packing plant in support of attempts by the workers to unionize.8 Epp-Koop notes that as an alderman “Penner twice put forward motions to protect strikers from police intimidation while picketing.”9 In 1935, Penner, along with councillor Martin Forkin, pressured city council to limit their interactions with the Winnipeg Free Press and the Winnipeg Tribune in solidarity with the strike by their typographical unions. The council agreed and the unionists, who didn’t always support the position of the communists, expressed their gratitude for such support on council.10

Penner was considered a deviant political outlier in civic politics. His elected colleagues were highly suspicious of his ideological intentions; his background in Russia only added another layer of doubt. Even within party ranks, Communist Party leaders expressed concern about the high representation of Eastern Europeans among the party’s members. According to Epp-Koop, while key national party leaders “enjoyed celebrating Jacob Penner’s victories, they thought he was not the party’s ideal standard bearer on city council because he was not Anglo-Saxon.”11

During the 1935 federal election the Penner family residence at 347 Lansdowne Avenue became Communist Party headquarters. A “Vote Tim Buck” sign on the front lawn became a target of rotten tomatoes (Buck was the national party leader and the local candidate).12 Even though the family supported Buck, tensions existed. As Roland Penner, Jacob’s son, remembered: “One day Buck stopped [in] when Jacob wasn’t home and Rose cornered him demanding some financial support, which he promised but never gave – quite a hypocrite. We were all sworn to secrecy; Dad would have been mortified.”13

In the early years of the Nazi regime, Penner was an outspoken opponent of fascism. In March 1934 he helped organize the Anti-Fascist League of Winnipeg.14 The Canadian version of the Nazi party, the Canadian Nationalist Party, had a presence in Winnipeg, and paraded through streets wearing Nazi brown shirts and bearing swastikas.15 Communist aldermen accused Mayor Ralph Webb of showing tolerance to fascist organizations, while he made it his personal mission to eradicate communists. He lobbied the federal government to deport communist agitators and even provided a list of names to the Minister of Immigration of Winnipeg communists who had travelled to Moscow. According to Penner’s son Norman, Webb said that if deportation were not possible he would “throw them into the Red River with Jake Penner being the first to go.”16

Imprisoned

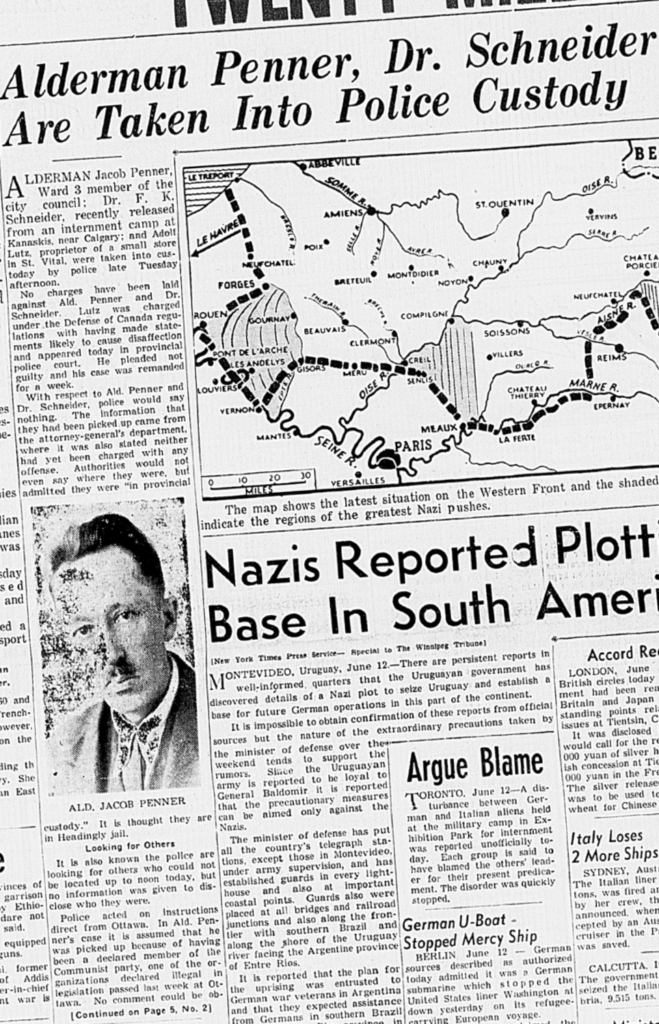

The Second World War heightened suspicions about anyone who did not support the war or mainstream political parties. Jacob Penner fit both those criteria. Being a Russian immigrant of German descent only added fuel to the fire, since Nazi Germany and Communist Russia had signed a non-aggression pact. Though Penner was strongly anti-fascist and thus anti-Nazi, his political ideology and ethnicity made him suspect.

The Liberal federal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King was concerned about political and security threats. In 1939 it issued the Defence of Canada Regulations, a set of emergency measures with sweeping powers implemented under the War Measures Act. Section 21 of the regulations allowed the Minister of Justice, Ernest Lapointe, to detain without charge anyone who might act “in any manner prejudicial to the public safety or the safety of the State.”17 The Communist Party of Canada was banned under the order. Fascists, communists, opponents of conscription (mostly French speakers from Quebec), German Canadians, Italian Canadians, labour leaders, Japanese newcomers, and others were placed under a magnifying glass.18 Anyone deemed a security risk could be arrested and detained as a prisoner of war.

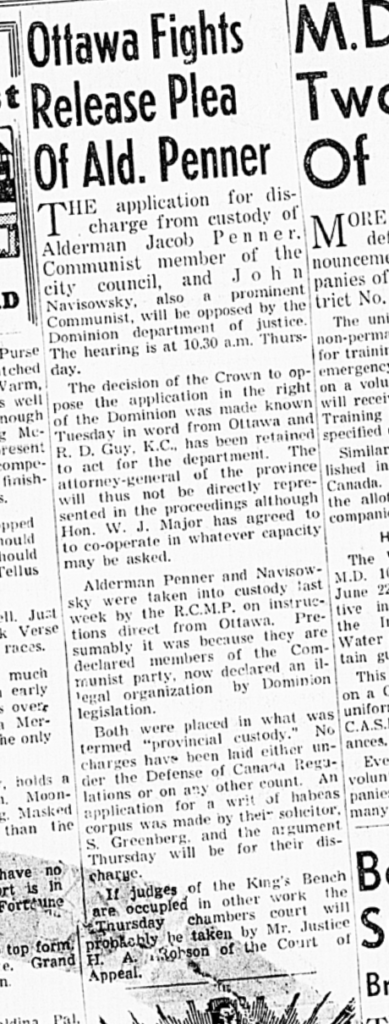

On June 11, 1940, eight police officers in two cruiser cars arrived at the Penner home to arrest Jacob.19 Calm and dignified, he asked to use the bathroom first. In passing, he discreetly handed Rose some papers from his pocket that held the names of other locals who might be at risk.20 Penner was taken into interim custody at the Headingley jail, where “he was intimidated and terrorized by prison guards with bullwhips and guns.”21 Penner had the distinction of being the first Canadian communist imprisoned during the Second World War under the Defence of Canada Regulations.22

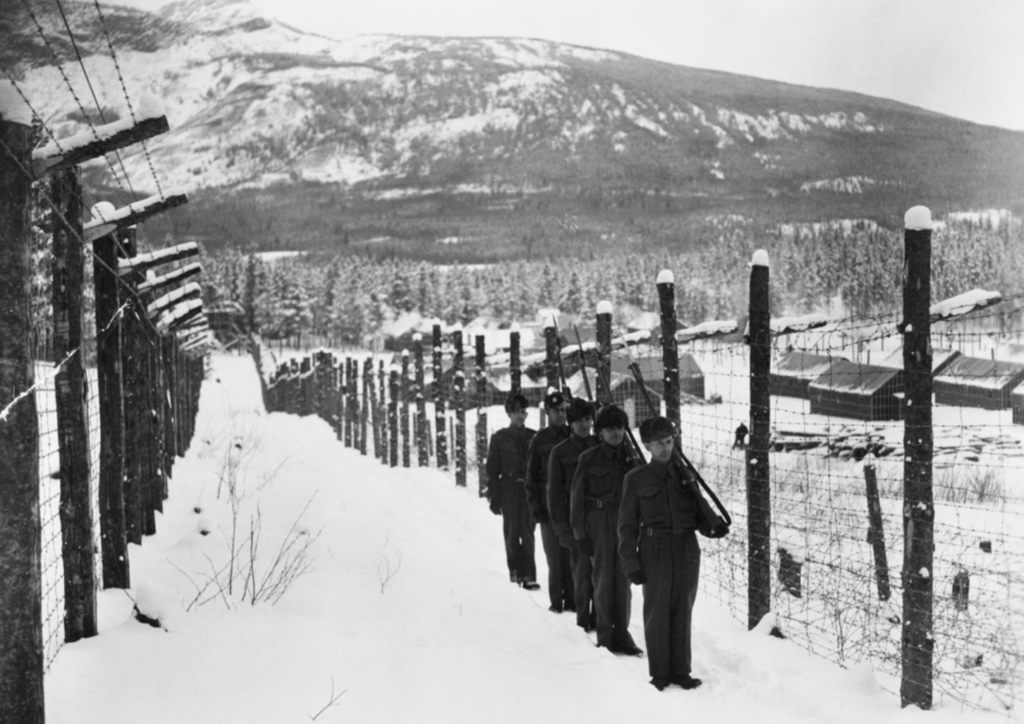

He was initially sent to an internment camp at Kananaskis, Alberta. Here he and other communists were housed with fascists and Nazis who harshly abused them and even threatened their lives. This, maintained Penner, was the most difficult part of his incarceration. Together with a group of communist sympathizers, he appealed to the camp commander for separate housing. As a result, the group was transferred to a military base at Petawawa, Ontario. When the train of detainees moved east toward Winnipeg, they dropped notes to train yard workers whom they knew would be supportive. Friends and family got word that the train was coming to Winnipeg with detained fathers and husbands and organized a meeting in the CPR yards. However, authorities got wind of the plan and shunted the car off to a secluded siding. “All we could do was wave and hope that our fathers and parents could see their loved ones,” said Roland. Jacob Penner would be transferred one more time, to a facility in Hull, Quebec, for unknown reasons.23

In detention Penner endeared himself to his fellow inmates. One recollected: “We imposed our own self-discipline on such matters as keeping neat, tidy and clean. In this respect we all admired Jacob Penner, the Communist Alderman from Winnipeg, already well advanced in years. His orderly, calm and methodical way of tackling all tasks and problems set an example for all of us.”24 A souvenir of Penner’s internment was a songbook he compiled for his fellow prisoners. Written in fine penmanship, the songbook held lyrics in German, Russian, French, and English, representing an eclectic mix of music hall ballads, revolutionary songs, and union songs.25

Attitudes toward Penner’s internment changed when the Soviets entered the war in the summer of 1941 on the side of the Allied powers. Winnipeg politicians from across the political spectrum advocated for his release.26 Penner was released in early September 1942.27 Headed home, he found himself by coincidence on the same westbound train to Winnipeg as his son Norman. During Jacob’s internment, Norman had married and moved to Toronto; he and his new wife were on their first trip to Winnipeg as a couple.

In Winnipeg, Jacob would receive the welcome of a lifetime. His son Roland recalled, “There were close to 5,000 people who came to greet my father, including every City Councillor who had earlier voted to take his council seat away.”28 Greeters also included members of the provincial legislature, the press, and “even the head of the Mennonite Church.”29 In the October election of that year, Penner again ran for council, landing at the top of the polls. Roland ascribed this to his “record of fighting so conscientiously for the rights of the working people, particularly during the late Depression.”30 The empathy his fellow politicians and other community leaders had expressed for Penner during and immediately after his imprisonment would subside once he was back in office and fighting for human rights under the banner of his communist ideology.

For Penner’s supporters, his political internment further cemented his reputation as a deeply principled man. Granddaughter Cathy Gulkin writes: “Jacob was well known for his impressive integrity which I believe also resulted from his Mennonite upbringing. When the War Measures Act was declared in Canada, the other leaders of the Communist Party of Canada went into hiding to avoid arrest. Jacob refused to do that.”31

Political Legacy

Over time Penner’s principled character became more widely known. His pursuit of elected office showed no hint of being motivated by desire for personal advancement. While appeals for help to some aldermen were unheard, brushed off, or ignored, Penner was attentive to his constituents. This was recognized by his political opponents. At a meeting of the Ukrainian Conservative Party, a man complained that his appearance at city council for help with a problem had yielded no results. The president told him, “Why don’t you go see Jake Penner? Jake Penner will do anything you want if it is at all possible.”32

Penner was very popular among his constituents in the city’s impoverished North End. He attracted support from across party and religious lines. Michael Harris, a Winnipeg Free Press reporter who covered the ethnic and labour beats, recounted a conversation with one of Penner’s constituents at the Ukrainian Labour Temple on Pritchard Avenue. In an undated anecdote, Harris asked the man how Penner always got voted back in even though there were not many communists in his ward. The man replied, “The people from St. Vladimir Cathedral, from St. Nicholas Church, from all these places, they go and vote for Penner because he is their friend. He helps them. Not nobody else.” Harris observed: “They’re Catholics and they’re Orthodox and they’re Protestant and of every different religion and of different political views – they supported him as alderman because he gave them service. He was their man. . . . He just helped a man because he needed help.”33

According to historian Brian McKillop, Penner’s political approach reflected his “ethic of conscience,” an ethic that finds its expression in movements that seek to effect major social change. He did not see politics as only a means of organization and administration, but rather as a means of applying moral and ethical philosophies to improve the human standard of living. Such an ethic is a bulwark against the discouragement of defeat; losing an election may shake a party, but the validity of a movement is not measured at the ballot box. “Politics” for Penner was not an activity worth of stigma, as it might be for some; it was “the touchstone of ethics.”34

Mennonites and their church leaders must have been flummoxed by Penner’s political participation. Penner’s ancestral Mennonite church on his father’s side, the Kleine Gemeinde, viewed anyone affiliated with government as suspect. Ron Dueck, of Kleine Gemeinde background, remarks, “We sort of took a dim view of being joined with government forces. . . . We were leery of people who rose up too high in power.”35 Whereas Mennonites looked askance at politics and felt threatened by and feared socialism, Penner saw opportunity for equality in lifting up the vulnerable and the marginalized from oppression.

Tainted by his atheism and communist ideology, the Mennonite community has taken little notice of Penner’s contributions to the history of Winnipeg civic politics. Equal unemployment benefits for all, social housing, the right to form labour unions, free education at all levels, and a minimum wage are just some of the goals Penner repeatedly fought for during his decades as a municipal politician. Such goals are central to Christian ideas of social justice, and are shared by many progressive Mennonites today.

On the occasion of his retirement, at eighty-one years old, Penner delivered an emotional farewell to his city council colleagues. According to the Free Press, “He warned council that unless man practices peace on earth and goodwill toward men, ‘the most stirring message man has ever received,’ we will perish.”36 Penner died after a brief illness on August 28, 1965, in Winnipeg. The epitaph on his headstone in Brookside Cemetery reads: “Beloved Champion of Justice, Peace and Socialism. ‘For he had a Glowing Dream.’”

In 2000, Jacob Penner’s name was somewhat elevated when city council dedicated a park to him. The vote did not occur without objection. Councillor Garth Steek opposed the gesture, saying, “My grandparents came to Canada from Russia to escape communist oppression. So did a lot of people and it’s objectionable to name a park after someone who represented that way of thinking.” Councillor Dan Vandal responded, “The Cold War is over. He devoted his life to the community.”37

- “Jacob Penner and Kolisnyk Open Campaign,” Winnipeg Evening Tribune, Oct. 30, 1931, 8.

- Norman Penner, Canadian Communism: The Stalin Years and Beyond (Toronto: Methuen, 1988), 122.

- Roland Penner, A Glowing Dream: A Memoir (Winnipeg: J. Gordon Shillingford Publishing, 2007), 38–39.

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 243n19.

- Brian McKillop, “A Communist in City Hall Winnipeg’s Centennial: Looking Back,” Canadian Dimension, Apr., 1974, 43. Mayor Ralph Webb’s policies consistently favoured business interests, and consistently clashed with Penner’s support for the working class.

- Stefan Epp-Koop, We’re Going to Run This City: Winnipeg’s Political Left after the General Strike (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2015), 96.

- Barbara Roberts, “Shovelling Out the Unemployed,” Manitoba History, no. 5 (1983), http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/05/shovellingunemployed.shtml; Epp-Koop, Run This City, 97.

- John Hanley Grover, “Winnipeg Meat Packing Workers’ Path to Union Recognition and Collective Bargaining” (master’s thesis, University of Winnipeg, 1996), 52–53.

- Epp-Koop, Run This City, 101.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 34.

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 49.

- Roland Penner, video interview by Cathy Gulkin, background for A Scattering of Seeds, White Pine Pictures, episode 33, 2000, Cathy Gulkin collection.

- “Anti-Fascist League of Winnipeg Organized,” Winnipeg Tribune, Mar. 3, 1934, 32.

- Epp-Koop, Run This City, 95.

- Epp-Koop, Run This City, 114.

- Defence of Canada Regulations (Ottawa: J. O. Patenaude, 1939), 29.

- Wikipedia, s.v. “Defence of Canada Regulations,” last modified Feb. 25, 2021.

- Norman Penner, Canadian Communism, 185; Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 59.

- Roland Penner, interview.

- Ruth Penner, video interview by Cathy Gulkin, background for A Scattering of Seeds, White Pine Pictures, episode 33, 2000, Cathy Gulkin collection.

- Norman Penner, Canadian Communism, 185.

- Roland Penner, “Transcript: Panel 3, Civilian Internment in Canada,” Oral History Forum d’histoire orale 36 (2016): 11. For the detail about dropping notes, Penner cites Ben Swankey, “Reflections of a Communist: Canadian Internment Camps,” Alberta History 30, no. 2 (1982): 11–21.

- Swankey, “Reflections of a Communist,” 17.

- Roland Penner, “Transcript: Panel 3,” 12; Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 61.

- Norman Penner, Canadian Communism, 185.

- “Jacob Penner is Released,” Winnipeg Tribune, Sept. 8, 1942, 1.

- Roland Penner, “Transcript: Panel 3,” 12.

- Roland Penner, Glowing Dream, 61. The Mennonite church leader is not named in Penner’s memoir. However, in 1942, official officers of the Conference of Mennonites in Canada were Benjamin Ewert (chair), J. J. Thiessen (vice-chair), and and Johann G. Rempel (secretary). It could have been any of these men, or someone else representing church leadership. If at this time Penner’s family was more connected to the Canadian Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches, it could have been Heinrich S. Voth (moderator), Jacob F. Redekop (assistant moderator), or G. D. Pries (secretary).

- Roland Penner, “Transcript: Panel 3,” 12.

- Cathy Gulkin, email correspondence, Aug. 20, 2019.

- McKillop, “A Communist in City Hall,” 48.

- Ibid., 49.

- Alexander Brian McKillop, “Citizen and Socialist: The Ethos of Political Winnipeg, 1919–1935” (master’s thesis, University of Manitoba, 1970), 90–95.

- Wendy and Ron Dueck, telephone interview, Nov. 20, 2020.

- “Alderman Penner Retires, Bids an Emotional Farewell,” Winnipeg Free Press, Dec. 28, 1961, 7.

- Epp-Koop, Run This City, 105

Also In this Issue

Proof in Material Culture: Mennonite Alcohol Consumption

Liquor Licenses: Winkler of the 1890s

Objections to Alcohol: The Rise and Fall of Temperance in Winkler

Mennonite Nectar: Alcohol Production in the Vistula Delta

Alcohol Production: In the Chortitza and Bergthal Colonies

Alcohol & Abstinence: Mennonites in South Russia

Addiction & Recovery: Mennonites in Mexico & Bolivia

Admonishment & Joy Deferred: Four Sermons of Aeltester Abraham L. Dueck

A Mennonite Travelogue: Martin B. Fast in South Russia

Whisky Sales and Hotel Tales of the Mennonite West Reserve, 1873-1916

Menno-Nightcaps: Cocktails Inspired by that Odd Ethno-Religious Group You Keep Mistaking for the Amish, Quakers or Mormons