Mennonite Nectar: Alcohol Production in the Vistula Delta

It might seem strange to readers that in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Vistula Delta Mennonites were known for producing hard liquor: Danziger Goldwasser, Stobbe’s Machandel, and Krambambuli. These liquors were widely consumed in Germany and even made minor appearances in well-known works of German literature. In one of Germany’s most frequently performed German plays, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s 1767 comedy Minna von Barnhelm, a main character drinks three (!) glasses of Goldwasser on an empty stomach first thing in the morning. The call for “Danziger, echter doppelter Lachs” in the original German isn’t really done justice by the English translation “real Danziger, double-distilled,” or “true Dantzig, real double-distilled.”

Other areas of German culture, such as student drinking songs, sometimes made explicit references to Mennonites. For example, Christoph Friedrich Wedekind’s 1745 poem praising distilled liquors from Danzig thanks the Vistula Mennonites for the creation of Krambambuli:

Nun Bürger von dem Weichselstrande,

Ihr Mennonisten habet Dank,

Es geh euch wohl zu Schiff und Lande,

Gott segne euren Nectartrank.

Leb, edles Danzig, grün und blüh,

Tusch! Vivat dein Krambambuli.1

(Now citizens of the Vistula shore,

Your Mennonists deserve thanks,

May you prosper on ship and land,

God bless your nectar-drink.

Live, noble Danzig, green and blooming,

Sound a fanfare! Long live Krambambuli.)

Although people have distilled since ancient times, the widespread consumption of distilled alcoholic beverages in Europe seems to have started in the fifteenth century. The distillation of liquor became common more recently than brewing and winemaking. Perhaps this is why Mennonites were so active in distilling, as the practice may have been less entrenched in the guild system than other occupations. Like the production of cheese, distilling was also a way of making use of and adding value to agricultural raw materials produced by rural Mennonites in the Vistula Delta. A few Vistula Mennonites made vinegar, some varieties of which are made from distilled alcohol.2

In the West Prussian Mennonite census of 1776, forty-five out of 2,639 family units, 1.7 percent of the Mennonite population, were involved in distilling or marketing liquor. They far outnumbered the other alcohol-related occupations – there were just six brewers (one household did both).3 In the city of Königsberg, in East Prussia, distilling was even more dominant. In 1732, seven out of twenty-one households were distillers, and several others also distilled and distributed distillery products alongside their primary occupations, such as lace-making and weaving. The large amount of taxes paid by the distillers protected their small Mennonite community from being expelled from East Prussia in 1732, when most other rural Mennonites were ordered to leave.4

The Salmon

On July 6, 1598, a Mennonite named Ambrosius Vermeulen was accepted as a citizen of Danzig, and soon began a tavern and distillery in the city. Vermeulen, who was from Lier, in present-day Belgium, had an appropriate first name, as ambrosia was the drink of the gods, conferring longevity. In the early eighteenth century the business moved to a house in the Breitgasse (Ulica Szeroka) known by the salmon-shaped sign above its front door, from which the company took the name Der Lachs (the salmon).5 The distillery was passed down through several generations of a complex Mennonite family network. After a granddaughter of Vermeulen married a Wedling and their daughter married a Hekker, the firm became associated with the names Wedling and Hekker, which appeared on the labels of their liquor bottles. A Hekker daughter then married a Bestvater. This couple did not have children, and the firm seems to have passed out of Mennonite hands after their deaths in the early nineteenth century.6 The distillery continued to operate into the twentieth century.

The Lachs distillery made a variety of liquors, but the most widely known were Goldwasser and Krambambuli.7 Goldwasser is an 80-proof, clear liqueur, slightly more viscous than water or alcohol, and spiced with cardamom, cloves, cinnamon, coriander, juniper, lavender, thyme, and maybe other flavours (the recipe likely evolved over time). The most distinctive feature is the food-grade gold flakes that float in the liquid, making its consumption visually conspicuous. Gold is not digested by the human body and is non-toxic. Krambambuli is a cherry liqueur popular in legendary German student drinking.

The original distillery location in Danzig (Gdańsk) was occupied by a restaurant named Salmon until late 2019, with a menu that included Goldwasser and salmon. The building was then emptied and a new restaurant opened, which has dropped the Salmon name but retains some of the previous decor and emphasizes its distillery heritage, serving Goldwasser, Machandel, Krambambuli, and several other liqueurs.

The legal right to distill alcoholic beverages in the town of Tiegenhof (Nowy Dwór Gdański) was attached to ownership of a specific property since as early as 1600. The property passed through several owners over the centuries, and the names of these that are known – Grunau, Wiebe, Thiessen, and Bestvater – could all have belonged to Mennonites. In 1763 Johann Donner became the owner. Donner was the father of Heinrich Donner, elder of the Orlofferfelde congregation and author of a congregational chronicle that is the source of many early stories about the Vistula Delta Mennonites. Heinrich’s son was another Johann Donner, who continued the chronicle and was also elder of the Orlofferfelde congregation.

The senior Johann Donner was married to Adelgunde Hekker, whose brother was Dirk Hekker, the contemporaneous owner of the Lachs distillery in Danzig. These Frisian families – Hekker, Bestvater, Thiessen, Grunau, and Stobbe – were intermarried in an extremely complex network that is very difficult to reconstruct clearly. The distilling business passed to Elder Heinrich Donner, whose first wife was Elisabeth Grunau and second wife was Elisabeth Stobbe. The oldest daughter, Adelgunde Donner, married Peter Stobbe, and the distillery passed down through their descendants until the late twentieth century.

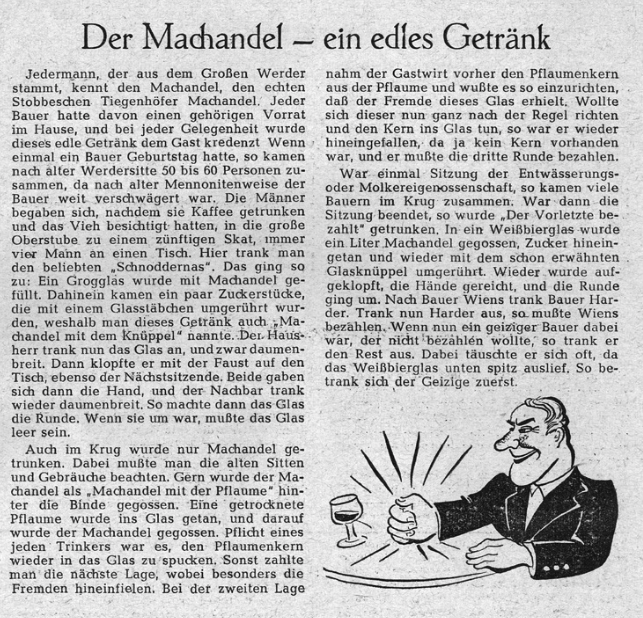

The Stobbe name was attached to the distillery’s most famous product, Machandel.8 This is a clear, 76-proof gin derived from juniper berries. There was a well-known ritual for drinking it that began with a prune soaked in a dilution of the liquor. The prune was speared on a toothpick and put into a chilled glass, and cold Machandel was poured over it. The drinker would take the prune and eat it, retaining the pit in his mouth (the drinkers were always men). He would then drink the Machandel in one swallow while holding the toothpick, spit the pit back into the glass, set the glass down, break the toothpick, and put it into the glass. Failure to follow the ritual required the drinker to buy everyone another round.

An anonymous article published in 1954 titled “Machandel – A Noble Drink,” shows how entrenched Machandel had become in Mennonite culture. “Everyone who comes from the Vistula Delta knows Machandel,” it stated, “the genuine Stobbe Tiegenhöfer Machandel. Every farmer had a good supply of it in the house, and served this noble drink to the guest at every opportunity. If a farmer had a birthday, fifty to sixty people would come together, according to old Delta customs, since in Mennonite circles they would all be related. After drinking coffee and inspecting the cattle, the men went to the large upper room for a hearty game of skat, always four men at a table. Here they drank the popular Schnoddernas (runny nose). It went like this: A grog glass was filled with Machandel. A few pieces of sugar were added and stirred with a glass rod, which is why this drink is also known as ‘Machandel with the cudgel.’ The host took the first drink, a thumb’s width. Then he banged the table with his fist, as did the person sitting next to him. Then they both shook hands and the neighbour drank, again a thumb’s width. So then the glass made the rounds. When it had gone all the way around, the glass must be empty.

“Likewise in the tavern, only Machandel was drunk. In doing so, one had to observe the old manners and customs. Gladly Machandel was guzzled as ‘Machandel with the plum.’ A dried plum was put into the glass, and the Machandel was poured onto it. It was the duty of every drinker to spit the plum pit back into the glass. Otherwise you paid for the next set, and strangers in particular fell victim. In the second round, the innkeeper took the plum pit out of the plum beforehand and arranged it so that the stranger received this glass. If he wanted to follow the rule and put the pit in the glass, he fell victim again, since there was no pit, and he had to pay for the third round.

“When the drainage or dairy cooperative met, many farmers would come together in a tavern. When the session was over, ‘next-to-last pays’ was drunk. A litre of Machandel was poured into a wheat beer glass, and sugar was poured in and again stirred with the aforementioned glass rod. The table was pounded again, hands shaken, and the glass went around. After farmer Wiens drank, then farmer Harder. If Harder finished it, Wiens had to pay. If there was a stingy farmer who did not want to pay, then he drank the remainder himself. He often deceived himself, as the wheat beer glass flared out wider at the bottom. So the cheapskate got drunk first.”9

Opposition

Temperance was uncommon among Vistula Mennonites, but there was some participation in local temperance groups, mostly by Mennonites who also participated in non-Mennonite mission societies. The Ellerwald and Rosenort church school libraries included publications from the local temperance society.10

Bernhard Regier, a minister at Heubuden, became a temperance advocate. Apparently, a group in his congregation tried to have him deposed as minister for his anti-alcohol advocacy.11 Regier continued his temperance position after he migrated to the United States in 1880 and became a minister at First Mennonite Church in Newton, Kansas, a congregation founded primarily by Vistula Mennonites. The congregation became strongly opposed to alcohol. At times, this stance conflicted with its belief in biblical inerrancy, for instance, when some members insisted that the use of grape juice for communion was unbiblical. It is unclear exactly when grape juice was first used instead of wine; there was a long transitional period when both were served. Wine continued to be served to some persons as late as 1965.12 Another congregation of Vistula Mennonites, First Mennonite of Beatrice, Nebraska, switched from wine to grape juice by congregational vote in 1958.13 Another early Kansas Mennonite advocate for temperance, Jacob G. Ewert, came to Hillsboro, Kansas, from the Vistula Valley congregation of Deutsch Kazun as a young child.14

Today

Both Goldwasser and Stobbe Machandel continued to be manufactured well into the twentieth century by revived or successor companies of the originals. Both now have gone out of production, although they have imitators, and a Stobbe descendant continues to make a “Stobbe 1776” liquor. The history of Mennonite liquor is still celebrated in the former Lachs restaurant, now Winne Grone, and in the restaurant Gdański Bowke, which encourages drinking Machandel according to the traditional ritual.15

- Stress on the second syllable. Der Krambambulist: Ein Lob-Gedicht über die Gebrannten Wasser im Lachs zu Danzig, dritte vermehrte und verbesserte Herausgab (n.p., 1747).

- The Mennonite census of 1776 showed two vinegar makers. Glenn Penner, “The Complete Census of Mennonites in West Prussia,” http://mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/1776_West_Prussia_Census.pdf. In Kaldowe there was a vinegar brewery, founded in 1732 by a Jacob Entz, which soon came into ownership by a Sudermann family. This business does not show up on the 1776 census. A. Driedger, “Aus der Geschichte der Mennonitengemeinde Heubuden,” Mennonitische Blätter, May 1939, 38.

- Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO), s.v. “Alcohol Among the Mennonites of Northeast Germany,” by Kurt Kauenhoven; Penner, “1776 Census.”

- Erich Randt, Die Mennoniten in Ostpreußen und Litauen bis zum Jahre 1772 (Königsberg: Otto Kümmel, 1912), 72.

- Joachim Bahlcke, “Die Danziger Liqueur-Fabrik ‘Der Lachs’: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Brauwesens in der Ostseemetropole,” Westpreußen-Jahrbuch 49 (1999): 100.

- Much of the family story is detailed in Clara Bestvater, “Das Geschlecht Bestvater,” Der Mennonit, Dec. 1956, 186–7, and Jan. 1957, 10–11.

- A price list from 1791 listed 97 different varieties. Bahlcke, 105.

- Stress on the second syllable. The Machandel story is detailed in Peter Backhaus, Stobbe Machandel: Von Tiegenhof/Westpreußen über Oldenburg in Oldenburg nach Wunsiedel/Fichtelgebirge (Barsbüttel: Backhaus, 2000).

- Der Westpreusse, Apr. 15, 1954, 15. Der Westpreusse newspaper was produced after World War II for former residents of the Vistula Delta.

- Mark Jantzen, Mennonite German Soldiers: Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772–1880 (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), 173. Driedger, “Aus der Geschichte,” mentions a temperance society in connection with Bible, tract, and mission societies in the Heubuden region (p. 59).

- John D. Thiesen, Prussian Roots, Kansas Branches: A History of First Mennonite Church of Newton (Newton, KS: Historical Committee of First Mennonite Church, 1986), 20.

- Thiesen, Prussian Roots, Kansas Branches, 113–114.

- God’s Love in Action: The Mennonite Community of Beatrice, Nebraska, 1876-1976 (Beatrice, NE: Beatrice Mennonite Church and First Mennonite Church, 1978), 57.

- GAMEO, s.v. “Ewert, Jacob G. (1874–1923),” by Christian Neff and J. W. Nickel.

- “Lost Traditions Revived: Machandel,” In Your Pocket City Guides, https://www.inyourpocket.com/gdansk/lost-traditions-revived-machandel_71233f.

Also In this Issue

Proof in Material Culture: Mennonite Alcohol Consumption

Liquor Licenses: Winkler of the 1890s

Objections to Alcohol: The Rise and Fall of Temperance in Winkler

Alcohol Production: In the Chortitza and Bergthal Colonies

Alcohol & Abstinence: Mennonites in South Russia

Addiction & Recovery: Mennonites in Mexico & Bolivia

The Political Life of Jacob Penner

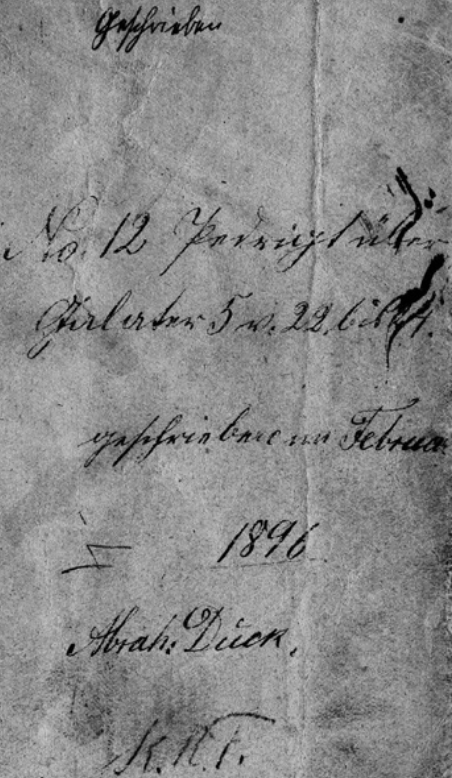

Admonishment & Joy Deferred: Four Sermons of Aeltester Abraham L. Dueck

A Mennonite Travelogue: Martin B. Fast in South Russia

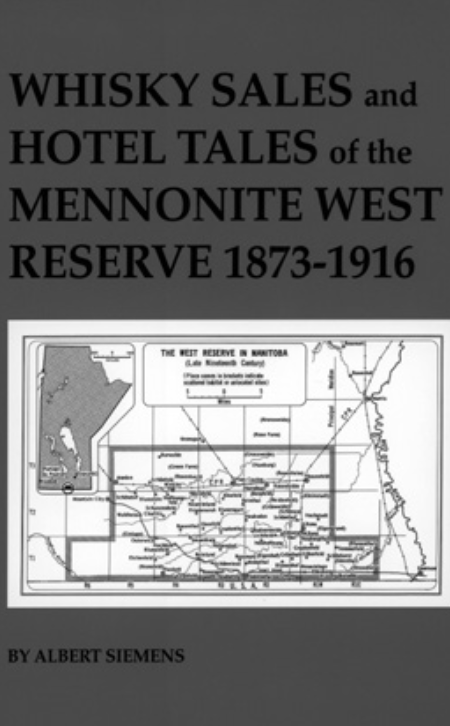

Whisky Sales and Hotel Tales of the Mennonite West Reserve, 1873-1916

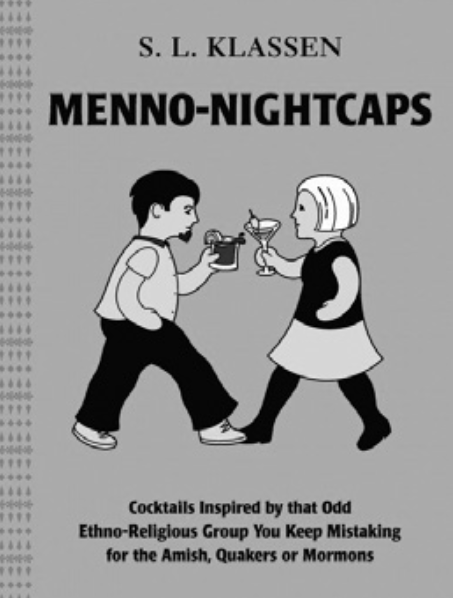

Menno-Nightcaps: Cocktails Inspired by that Odd Ethno-Religious Group You Keep Mistaking for the Amish, Quakers or Mormons